3

Skull

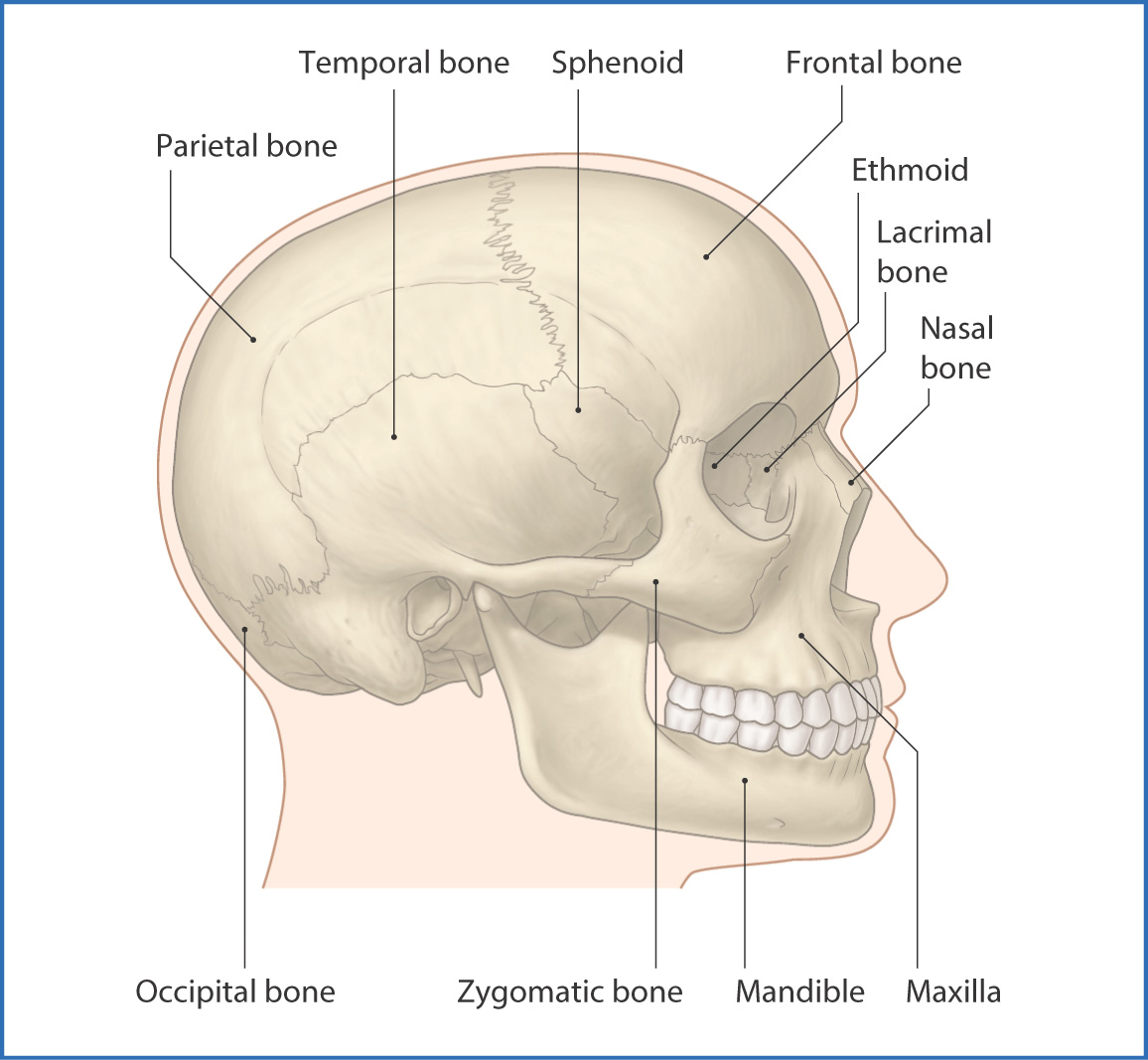

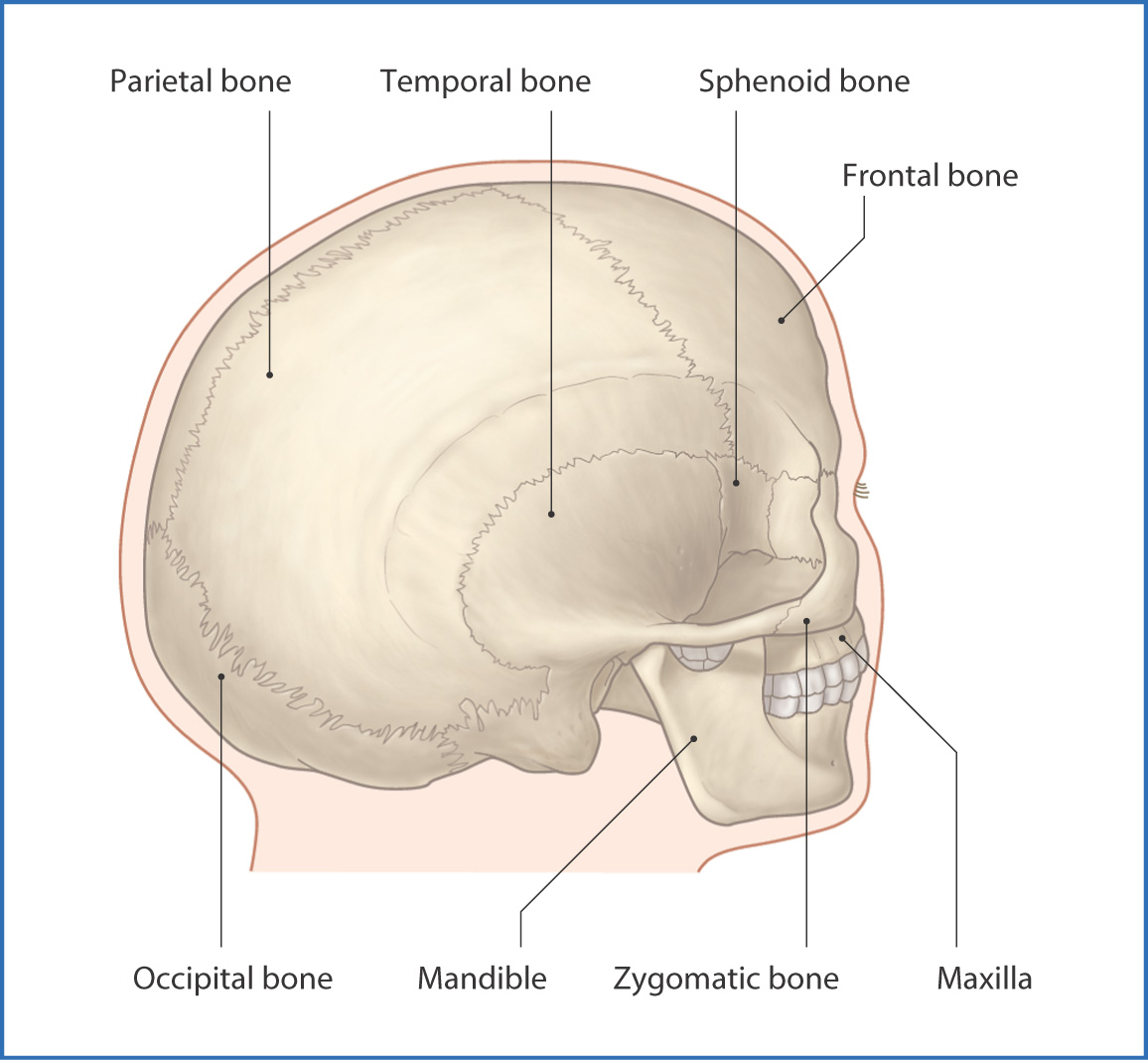

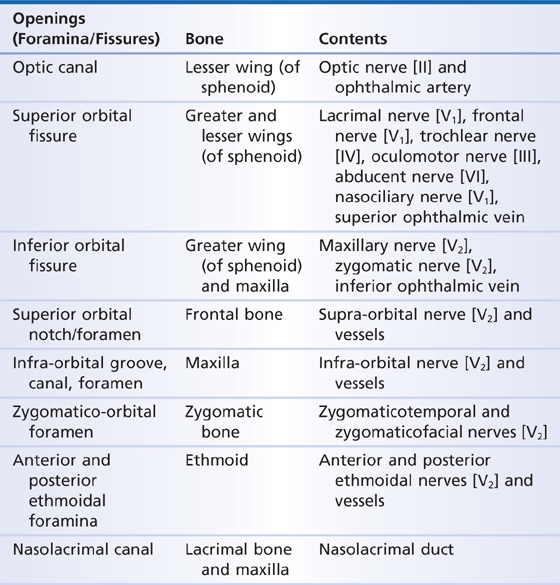

The skull (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2) is formed by bones that protect the brain and areas associated with the special senses of sight, hearing, taste, and smell. The skull also houses entrances for the respiratory and digestive systems—the nose and mouth, respectively. Numerous other openings (canals, fissures, and foramina) in the skull serve as conduits for the spinal cord, cranial nerves, and blood vessels (Table 3.1). The muscles of facial expression and mastication also attach to the skull.

FIGURE 3.1 Lateral view of the bones of the skull.

FIGURE 3.2 Posterolateral view of the bones of the skull.

TABLE 3.1 Openings in the Skull

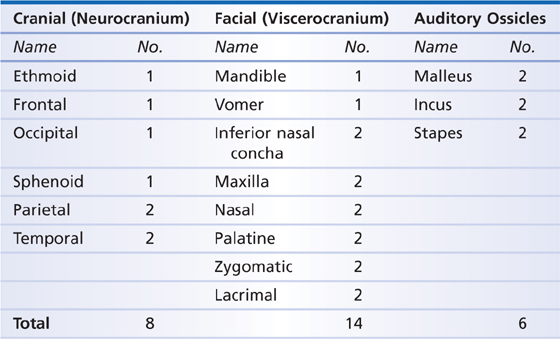

The bones of the skull are divided into three groups (Table 3.2):

- 8 cranial bones form the neurocranium, which protects the brain

- 14 facial bones form the viscerocranium, which provides the substructure for the face

- 6 auditory ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), three in each ear

- 14 facial bones form the viscerocranium, which provides the substructure for the face

TABLE 3.2 Bones of the Skull

The total number of bones in the skull is therefore 28.

All bones of the skull, except the mandible and ear ossicles, articulate at serrated immovable sutures. They are separated by a thin layer of fibrous connective tissue that is continuous with the periosteum. The sutures between the skull bones fuse and become less distinct with age. The plate-like bones of the neurocranium (also known as the calvarium) consist of external and internal tables of compact bone, with diploë (cancellous bone) between.

Treatment of skull fractures varies, depending on whether the external or internal table is damaged (see p. 14).

Nerves

Sensory innervation of the skull is provided by the meningeal branches of several of the cranial and cervical spinal nerves:

- The anterior cranial fossa is innervated by the ophthalmic nerve [V1]—the first division of the trigeminal nerve [V]—which originates at the trigeminal ganglion. Ethmoidal nerves branch off the ophthalmic nerve [V1] and, in turn, branch into the meningeal branches that innervate the anterior cranial fossa.

- Meningeal branches of the other two branches of the trigeminal nerve [V], the maxillary [V2] and mandibular [V3] nerves, innervate the middle cranial fossa.

- Nerve fibers from cervical spinal nerves C2 and C3 follow the hypoglossal nerve [XII] to the oral region and upper part of the neck, where they innervate muscles and other structures.

- C2 fibers carried by the vagus nerve [X] supply the posterior cranial fossa.

- Meningeal branches of the other two branches of the trigeminal nerve [V], the maxillary [V2] and mandibular [V3] nerves, innervate the middle cranial fossa.

Extracranial sensory innervation of the skull is provided by periosteal branches of the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve [V]—the ophthalmic nerve [V1], maxillary nerve [V2], and mandibular nerve [V3]. These branches supply the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the face, respectively. The posterior aspect of the skull is innervated by posterior rami of the greater occipital nerve (C2) and the third occipital nerve (C3).

Brain and Cranial Nerves

CRANIAL NERVES

Cranial nerves arise from the brain and brainstem and are paired and numbered in a craniocaudal sequence. They innervate structures in the head and neck. The vagus nerve [X] also innervates structures in the thorax and abdomen (see Table 3.4).

BRAIN

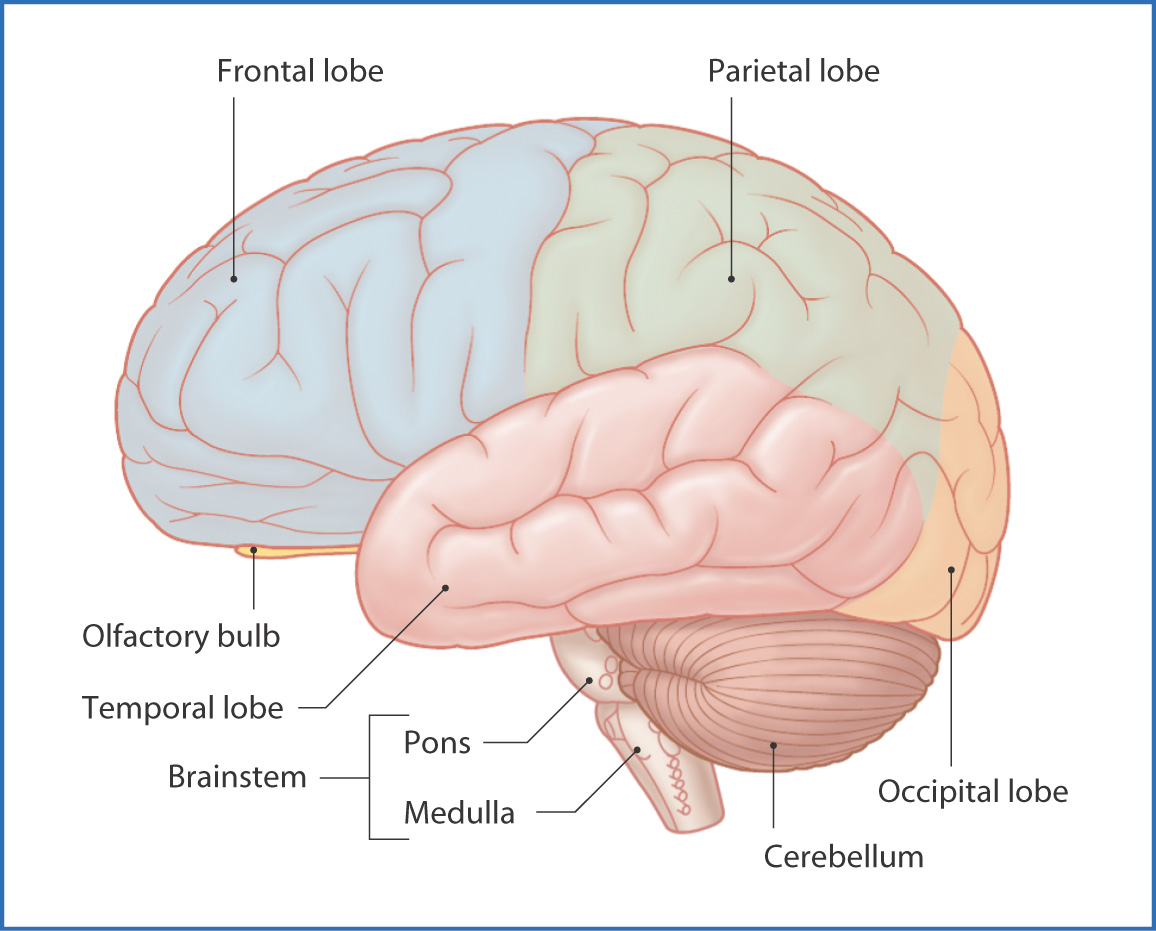

The brain has three primary regions: cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4). The cerebrum is made up of four lobes. The frontal lobe is responsible for higher mental functions such as decision making. The parietal lobe plays a role in receiving sensory information, initiating movement, and perception of objects. The temporal lobe is involved in memory, hearing, and speech. The occipital lobe is responsible for vision. The left and right hemispheres of the cerebrum are joined in the midline by the corpus callosum, a series of densely arranged nerve fibers that facilitate communication between hemispheres.

FIGURE 3.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree