DRUG CLASSES

pioid agonists

pioid agonist-antagonists

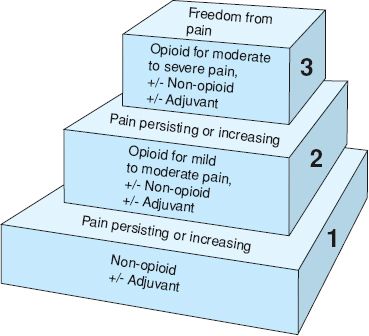

Pain and its treatment are universal issues. In this chapter the opioid drugs used for severe pain are discussed as well as how the intensity of pain determines the use of these drugs. The World Health Organization (WHO) developed a three-step analgesic protocol based on intensity as a guideline for treating pain. This “pain ladder” directs the use of both opioid and nonopioids in the treatment of pain using three steps (Fig. 15.1). For mild pain, a Step 1 nonopioid analgesic may be prescribed. If necessary, an adjuvant (extra helping) agent may be used to promote the pain-relieving effect. If pain persists or worsens even with appropriate dosage increases, a Step 2 or Step 3 analgesic is indicated. Step 2 and Step 3 analgesics contain opioid substances. Most patients with severe pain require a Step 2 or Step 3 analgesic.

Opioid is the general term used for the opium-derived or synthetic analgesics used to treat moderate to severe pain. The opioid analgesics are controlled substances (see Chapter 1). The analgesic properties of opium have been known for hundreds of years. These drugs do not change the tissues where the pain sensation originates; instead, they change how the patient perceives the pain.

PHARMACOLOGY IN PRACTICE

Mrs. Moore is taking morphine sulfate to manage severe pain occurring as the result of heart failure. The primary health care provider has prescribed an around-the-clock dosage regimen. Mrs. Moore tells you that she is taking the pain drug 1 to 2 hours before the next dose is due. As you read this chapter, think about the appropriate response to her statement about taking her medicine on a more frequent schedule.

Figure 15.1 World Health Organization pain relief ladder. (Adapted with permission from WHO [2012].)

OPIOID ANALGESICS

The opiates are natural substances and include morphine sulfate,* codeine, opium alkaloids, and tincture of opium. Synthetic opioids are those manufactured analgesics with properties and actions similar to the natural opioids. Examples of synthetic opioid analgesics are methadone, levorphanol, remifentanil, and meperidine. Morphine sulfate, when extracted from raw opium and treated chemically, yields the semisynthetic opioids hydromorphone, oxymorphone, oxycodone, and heroin.

Heroin is an illegal narcotic substance in the United States and is not used in medicine. Narcotic is a term referring to the properties of a drug to produce numbness or a stupor-like state. Although the terms opioid and narcotic were once interchangeable, law enforcement agencies have generalized the term narcotic to mean a drug that is addictive and abused or used illegally. Health care providers use the term opioid to describe drugs used in pain relief. Additional analgesics are listed in the Summary Drug Table: Opioid Analgesics.

Actions

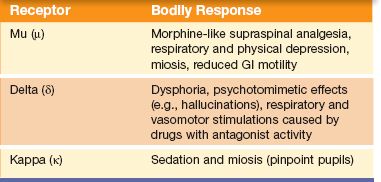

Cells in the central nervous system (CNS) have receptor sites called opiate receptors. Although opiates are attracted to many different receptor sites, the mu (µ) and kappa (κ) receptors produce the analgesic, sedative, and euphoric effects associated with analgesic drugs.

Drugs that bind well to a receptor are called agonist agents. An opioid analgesic may be classified as an agonist, partial agonist, or mixed agonist-antagonist. The agonist binds to a receptor and causes a response. A partial agonist binds to a receptor, but the response is limited (i.e., is not as great as with the agonist). An agonist-antagonist has properties of both the agonist and antagonist. These drugs have some agonist activity at the receptor sites and some antagonist activity at the receptor sites. Antagonists bind to a receptor and cause no response. An antagonist can reverse the effects of the agonist. This reversal is possible because the antagonist competes with the agonist for a receptor site. Drugs that act as opioid antagonists are discussed in Chapter 16.

In addition to the pain-relieving effects, other, nonintended responses occur when the opiate receptor sites are stimulated. These include respiratory depression, decreased gastrointestinal (GI) motility, and miosis (pinpoint pupils). Table 15.1 identifies the responses in the body associated with three of the opiate receptors. The actions of the opioid analgesics on the various organs and structures of the body (also called secondary pharmacologic effects) are shown in Display 15.1. With long-term use, the patient’s body adapts to these secondary effects. The only bodily system that does not adapt and compensate is the GI system. Slow GI motility and the resulting constipation are always a problem in opioid therapy.

The most widely used opioid, morphine sulfate, is an effective drug for moderately severe to severe pain. Morphine sulfate is considered the prototype (model) opioid. Morphine sulfate also is considered the gold standard in pain management—morphine sulfate’s actions, uses, and ability to relieve pain are the standards against which other opioid analgesics are often compared. Charts called equal-analgesic conversions compare other opioid doses with the doses of morphine sulfate that would be used for the same level of pain control.

Other opioids, such as meperidine and levorphanol, are effective for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. For mild to moderate pain, the primary health care provider may order an opioid such as codeine or pentazocine.

Table 15.1 Bodily Responses Associated With Opioid Receptor Sites

Display 15.1 Secondary Pharmacologic Effects of the Opioid Analgesics

• Cardiovascular—peripheral vasodilation, decreased peripheral resistance, inhibition of baroreceptors (pressure receptors located in the aortic arch and carotid sinus that regulate blood pressure), orthostatic hypotension, and fainting

• Central nervous system—euphoria, drowsiness, apathy, mental confusion, alterations in mood, reduction in body temperature, feelings of relaxation, dysphoria (depression accompanied by anxiety); nausea and vomiting are caused by direct stimulation of the emetic chemoreceptors located in the medulla. The degree to which these occur usually depends on the drug and the dose.

• Dermatologic—histamine release, pruritus, flushing, and red eyes

• Gastrointestinal—decrease in gastric motility (prolonged emptying time); decrease in biliary, pancreatic, and intestinal secretions; delay in digestion of food in the small intestine; increase in resting tone, with the potential for spasms, epigastric distress, or biliary colic (caused by constriction of the sphincter of Oddi). These drugs can cause constipation and anorexia.

• Genitourinary—urinary urgency and difficulty with urination, caused by spasms of the ureter. Urinary urgency also may occur because of the action of the drugs on the detrusor muscle of the bladder. Some patients may experience difficulty voiding because of contraction of the bladder sphincter.

• Respiratory—depressant effects on respiratory rate (caused by a reduced sensitivity of the respiratory center to carbon dioxide)

• Cough—suppression of the cough reflex (antitussive effect) by exerting a direct effect on the cough center in the medulla. Codeine has the most noticeable effect on the cough reflex.

• Medulla—Nausea and vomiting can occur when the chemoreceptor trigger zone located in the medulla is stimulated. To a varying degree, opioid analgesics also depress the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Therefore, nausea and vomiting may or may not occur when these drugs are given.

Uses

The opioid analgesics are used primarily for the treatment of moderate to severe acute and chronic pain and in the treatment and management of opiate dependence. Morphine sulfate is one of the primary drugs included in Hospice Comfort Care Medicine Packs (see Appendix E). In addition, the opioid analgesics may be used for the following reasons:

• To decrease anxiety and sedate the patient before surgery. Patients who are relaxed and sedated when an anesthetic agent is given are easier to anesthetize (requiring a smaller dose of an induction anesthetic), as well as easier to maintain under anesthesia.

• To support anesthesia (i.e., as an adjunct during anesthesia)

• To promote obstetric analgesia

• To relieve anxiety in patients with dyspnea (breathing difficulty) associated with pulmonary edema

• Administered intrathecally (a single injection into spinal cord space) or epidurally (catheter placed into spinal cord space for multiple injections), to control pain for extended periods without apparent loss of motor, sensory, or sympathetic nerve function

• To relieve pain associated with a myocardial infarction (morphine sulfate is the agent of choice)

• To manage opiate dependence

• To induce conscious sedation before a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure in the hospital setting

• To treat severe diarrhea and intestinal cramping (camphorated tincture of opium may be used)

• To relieve severe, persistent cough (codeine may be helpful, although the drug’s use has declined)

Adverse Reactions

Central Nervous System Reactions

• Euphoria, weakness, headache

• Lightheadedness, dizziness, sedation

• Miosis, insomnia, agitation, tremor

• Increased intracranial pressure, impairment of mental and physical tasks

Respiratory System Reactions

• Depression of rate and depth of breathing

Gastrointestinal System Reactions

• Nausea, vomiting

• Dry mouth, biliary tract spasms

• Constipation, anorexia

Cardiovascular System Reactions

• Facial flushing

• Tachycardia, bradycardia, palpitations

• Peripheral circulatory collapse

Genitourinary System Reactions

• Urinary retention or hesitancy

• Spasms of the ureters and bladder sphincter

Allergic and Other Reactions

• Pruritus, rash, and urticaria

• Sweating, pain at injection site, and local tissue irritation

Contraindications

All opioid analgesics are contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to the drugs. These drugs are contraindicated in patients with acute bronchial asthma, emphysema, or upper airway obstruction and in patients with head injury or increased intracranial pressure. The drugs are also contraindicated in patients with convulsive disorders, severe renal or hepatic dysfunction, and acute ulcerative colitis. The opioid analgesics are pregnancy category C drugs (oxycodone is in pregnancy category B) and are not recommended for use during pregnancy or labor because they may prolong labor or cause respiratory depression in the neonate. The use of opioid analgesics is recommended during pregnancy only if the benefit to the mother outweighs the potential harm to the fetus.

Precautions

Opioid analgesics should be used cautiously in older adults and in patients considered opioid naive, that is, who have not been medicated with opioid drugs before and who are consequently at greatest risk for respiratory depression. The drugs should be administered cautiously in patients undergoing biliary surgery (because of the risk for spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, between the bile duct and small intestine; in these patients, meperidine is the drug of choice). Patients who are lactating should wait at least 4 to 6 hours after taking the drug to breastfeed the infant. Additional precautions apply to patients with undiagnosed abdominal pain, hypoxia, supraventricular tachycardia, prostatic hypertrophy, and renal or hepatic impairment.

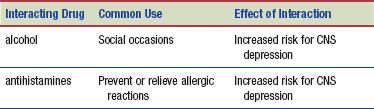

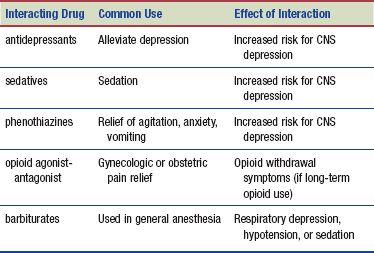

Interactions

The following interactions may occur when an opioid analgesic is administered with another agent:

HERBAL CONSIDERATIONS

HERBAL CONSIDERATIONS

The name passionflower denotes many of the approximately 400 species of herbs in the genus Passiflora. Passionflower has been used in medicine to treat pain, anxiety, and insomnia. Some herbalists use it to treat symptoms of parkinsonism. Passionflower is often used in combination with other natural substances, such valerian, chamomile, and hops, for promoting relaxation, rest, and sleep. Although no adverse reactions have been reported, large doses may cause CNS depression. The use of passionflower is contraindicated in pregnancy and in patients taking the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Passionflower contains coumarin; the risk of bleeding may be increased in patients taking warfarin (Coumadin) and passionflower. The following are recommended dosages for passionflower:

• Tea: 1–4 cups per day (made with 1 tablespoon of the crude herb per cup)

• Tincture (2 g/5 mL): 2 teaspoons (10 mL) 3–4 times daily

• Dried herb: 2 g 3–4 times daily (DerMarderosian, 2003)

NURSING PROCESS

PATIENT RECEIVING AN OPIOID ANALGESIC FOR PAIN

ASSESSMENT

Preadministration Assessment

As part of the preadministration assessment, assess and document the type, onset, intensity, and location of the pain. Your documentation should include a description of the pain (e.g., sharp, dull, stabbing, throbbing) and an estimate of when the pain began. Treat each different pain like it is a new pain. Use the questions in Chapter 14 (Guidelines and questions for a pain assessment) if the pain is of a different type than the patient had been experiencing previously or if it is in a different area.

Review the patient’s health history, allergy history, and past and current drug therapies. This is especially important when an opioid is given for the first time because data may be obtained during the initial history and physical assessment that require the nurse to contact the primary health care provider. For example, the patient may state that nausea and vomiting occurred when he or she was given a drug for pain several years ago. Further questioning of the patient is necessary because this information may influence the primary health care provider’s decision to administer a specific opioid drug.

If promethazine (Phenergan) is used with an opioid to enhance the effects and reduce the dosage of the opioid, take the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate before giving the drug.

Ongoing Assessment

You can measure the effect of the opioid by taking the blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate, and pain rating in 5 to 10 minutes if the drug is given intravenously (IV), 20 to 30 minutes if the drug is administered intramuscularly (IM) or subcutaneously (subcut), and 30 or more minutes if the drug is given orally. It is important to notify the primary health care provider if the analgesic is ineffective, because a higher dose or a different opioid analgesic may be required.

During the ongoing assessment, it is important for you to ask about the pain regularly and to accept the patient’ and family’s reports of pain. Nursing judgment must be exercised, because not all instances of a change in pain type, location, or intensity require notifying the primary health care provider. For example, if a patient recovering from recent abdominal surgery experiences pain in the calf of the leg (suggesting venous thrombosis), you should immediately notify the primary health care provider. However, it is not necessary to contact the primary health care provider for pain that is slightly worse because the patient has been moving in bed.

The opioid-naive patient who does not use opioids routinely and is being given an opioid drug for acute pain relief or a surgical procedure is at greatest risk for respiratory depression after opioid administration. Respiratory depression may occur in patients receiving a normal dose if the patient is vulnerable (e.g., in a weakened or debilitated state). Older, cachectic (malnourished/in general poor health), or debilitated patients should receive a reduced initial dose until their response to the drug is known. If the patient’s respiratory rate is 10 breaths/min or less, monitor the patient at more frequent intervals and notify the primary health care provider immediately. Patients involved in long-term opioid therapy for pain relief build tolerance to the physical adverse effects of the drugs; respiratory depression is typically not seen in these patients.

When an opiate is used as an antidiarrheal drug, document each bowel movement, as well as its appearance, color, and consistency. Notify the primary health care provider immediately if diarrhea is not relieved or becomes worse, if the patient has severe abdominal pain, or if blood in the stool is noted.

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Drug-specific nursing diagnoses are the following:

Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to pain and effects on breathing center by opioids

Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to pain and effects on breathing center by opioids

Risk for Injury related to dizziness or lightheadedness from opioid administration

Risk for Injury related to dizziness or lightheadedness from opioid administration

Constipation related to the decreased GI motility caused by opioids

Constipation related to the decreased GI motility caused by opioids

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to anorexia caused by opioids

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to anorexia caused by opioids

Nursing diagnoses related to drug administration are discussed in Chapter 4.

PLANNING

The expected outcomes of the patient may include relief of pain, supporting the patient needs related to the management of adverse reactions, an understanding of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA; when applicable), absence of injury, adequate nutrition intake, and confidence in an understanding of the medication regimen.

Figure 15.2 Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) allows the patient to self-administer medication as necessary to control pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree