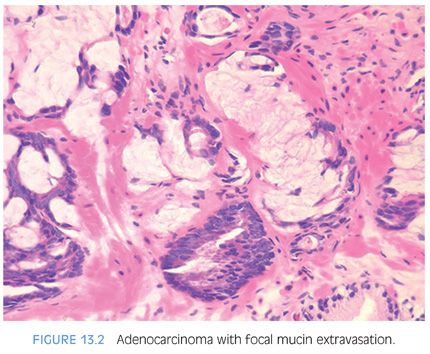

Mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland is one of the least common morphologic variants of prostatic carcinoma.5–7 A lack of precision in the definition of these mucinous neoplasms has resulted in reports that have overstated the incidence of this rare variant. Much of the confusion in the terminology of this entity arises from the lack of recognition that between 60% and 90% of prostatic adenocarcinomas secrete mucosubstances, depending on the histochemical technique used.1,8–10 Only when extracellular mucin is secreted in sufficient quantity to result in pools of mucin should the term mucinous be employed. If the mucinous area occupies only a small portion of the tumor, it should not be called a “mucinous prostatic carcinoma” but rather a “prostatic adenocarcinoma with focal mucinous features.” Using criteria developed for mucinous carcinomas of other organs, the diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland should be made when at least 25% of the tumor resected contains lakes of extracellular mucin.6 Defined as such, this variant forms less than 1% of all prostate adenocarcinoma.11 The diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma cannot be established on needle biopsy because the entire tumor is not available for examination. Rather, on needle biopsy, one can diagnose “adenocarcinoma of the prostate with mucinous features.”

In a more recent large series from our group, Osunkoya et al.11 reported the clinicopathologic findings of 47 mucinous adenocarcinomas of the prostate treated by radical prostatectomy. Mean patient age at diagnosis was 56 years. The mean preoperative PSA level was 9.0 ng/mL (range: 1.9 to 34.3 ng/mL). The majority of tumors (72%) were clinical stages T1c and Gleason score 7 (78.7%). Taking into account both the mucinous and nonmucinous tumor components, 43% of cases had extraprostatic extension and 13% had positive margins. Only one case was positive for lymph node metastasis.

The clinical behavior of mucinous prostate adenocarcinomas has been somewhat controversial. Although initial studies, including one from our group, suggested an aggressive biologic behavior,5–7 our more recent larger series mentioned earlier indicates that mucinous adenocarcinoma of the prostate treated by radical prostatectomy is not more aggressive and possibly is even less aggressive than conventional acinar prostatic adenocarcinoma. With a mean follow-up of 5.6 years, the study by Osunkoya et al.11 reported progression in only 1 out of 47 patients (2.1%) with a 5-year actuarial progression-free risk of 97% compared to 85% for nonmucinous prostate cancer with matched PSA and postoperative findings. This favorable prognosis is in line with the findings of another recent study by Lane et al.12

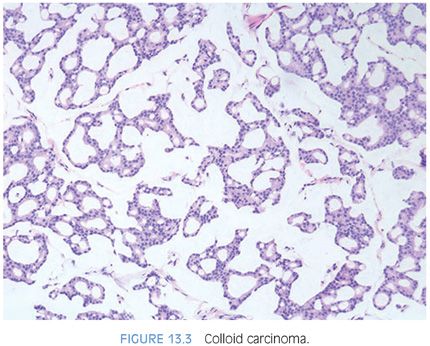

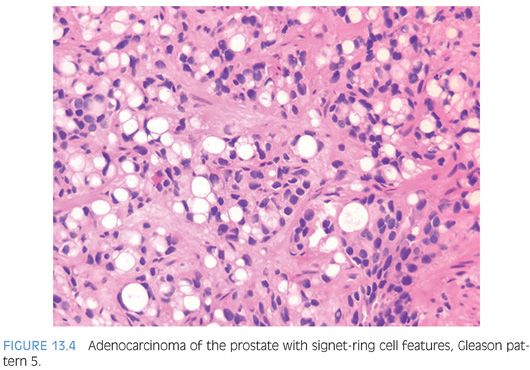

Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the prostate, similar to usual acinar adenocarcinomas, are associated with elevated serum PSA values, metastasize to bone, and respond to hormonal therapy. Histologically, mucinous adenocarcinomas of the prostate are predominantly Gleason score 7 or 8 as a cribriform pattern tends to predominate in the mucinous areas (see Chapter 9 for grading)11,13 (Figs. 13.2 to 13.3, eFigs. 13.20 to 13.36). In contrast to bladder adenocarcinomas, mucinous adenocarcinoma of the prostate rarely contains mucin-positive signet cells. Some adenocarcinomas of the prostate will have a signet-ring cell appearance, yet the vacuoles do not contain intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 13.4, eFigs. 13.37 to 13.43).14 Only a few cases of prostate cancer have been reported with mucin-positive signet cells.15,16 In one of these cases, the signet cell carcinoma appeared to arise from intestinal metaplasia of the overlying urothelium.17

At the molecular biologic level, mucinous adenocarcinomas of the prostate demonstrate a higher rate of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion (83% compared to approximately 50% of usual acinar adenocarcinoma).18 Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the prostate shows frequent and diffuse expression of MUC2, a “gel-forming” type of mucin that exerts a tumor suppressor role in other exocrine mucinous adenocarcinomas including pancreatic and breast colloid carcinomas. MUC2 is absent in normal prostatic glands and is not expressed in the majority of conventional acinar adenocarcinomas of the prostate. The high rate of MUC2 expression in mucinous adenocarcinoma of the prostate may play a role, not only in its colloid differentiation but also in its relatively indolent behavior that has been recently elucidated as discussed earlier.19

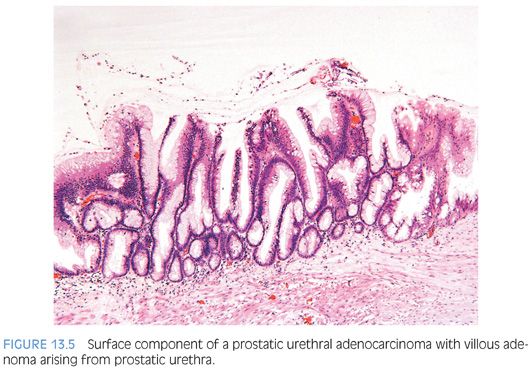

Our group and others have described the occurrence of prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma that arises through a process of glandular metaplasia of the prostatic urethral urothelium, sometimes associated with villous adenoma, and subsequent in situ adenocarcinoma with invasion into the prostate (Fig. 13.5, eFigs. 13.44 to 13.54).20–24 These prostatic adenocarcinomas are analogous to nonurachal adenocarcinomas arising in the bladder in a background of cystitis glandularis. The distinction between usual adenocarcinoma of the prostate, adenocarcinoma from another organ secondarily involving the prostate (typically gastrointestinal [GI] tract), and prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma has significant therapeutic implications, as in the latter two situations, the tumors are not prostatic in origin despite involving the prostate. Our largest recent series included 15 cases of prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma with a mean patient age at diagnosis of 72 years. All men had negative colonoscopies, clinically excluding a colonic primary. Bladder primaries were also ruled out clinically and/or pathologically. On follow-up (mean 50 months), over one-quarter of patients developed metastatic disease and approximately half died of disease. Glandular metaplasia of the prostatic urethra and contiguous transition to adenocarcinoma were identified in approximately half of the cases. Multiple histologic patterns were observed including dissection of the stroma by mucin pools (100%), villous features (47%), necrosis (13.3%), and presence of signet ring cells (20%). On immunohistochemical stains, all cases were negative for PSA, CDX2, and beta-catenin, whereas high molecular weight cytokeratin, CK7, and CK20 were positive in the majority of cases. As prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma is entirely analogous to bladder adenocarcinoma in both morphology and immunophenotype, only clinical studies or, in some cases, pathologic examination of the cystoprostatectomy specimen can exclude infiltration from a primary bladder adenocarcinoma. Ductal adenocarcinomas of the prostate may cytologically resemble these tumors; however, prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma lacks extracellular mucin and is immunohistochemically uniformly positive for PSA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree