Clinical prostatitis may give rise to elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) elevations.8 There are conflicting studies as to whether histologic evidence of either acute or chronic inflammation on biopsy correlates with an increase in total serum PSA levels.9–13 We comment on the histologic presence of chronic inflammation only when it is prominent, as it is fairly ubiquitous. The presence of acute inflammation, except if only very focal, is noted in the report. Acute and chronic inflammation may result in both architectural and cytologic abnormalities that may be confused with carcinoma (see Chapter 10).

MALAKOPLAKIA

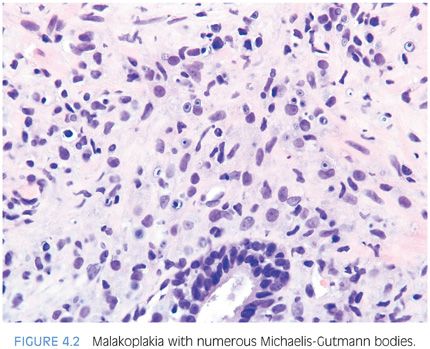

As in the bladder, the majority of men with prostatic malakoplakia have urinary tract infections, most frequently with Escherichia coli.14–16 Malakoplakia may clinically mimic cancer, resulting in prostatic induration and a hypoechoic lesion seen on transrectal ultrasound. Histologically, the lesions are indistinguishable from those occurring in other sites (Fig. 4.2, eFig. 4.5).

SARCOIDOSIS

Sarcoidosis of the prostate is an extremely rare occurrence. Only four cases have been reported in the literature where clinically documented sarcoidosis was associated with sarcoidal lesions on prostate biopsy. Like nonprostatic sites, ruling out an infectious etiology is a prerequisite for the diagnosis.17

GRANULOMATOUS PROSTATITIS

Granulomatous prostatitis is subclassified into infectious granulomas, nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis, postbiopsy resection granulomas, and systemic granulomatous prostatitis.18,19 In a series of 200 cases of granulomatous prostatitis, nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis (138 cases) and postbiopsy granulomas (49 cases) were the most common. Infectious granulomatous prostatitis occurred in only 7 cases, with the remaining 6 due to systemic granulomatous disorders.18

MYCOTIC PROSTATITIS

Fungal infections of the prostate usually occur in immunocompromised hosts with disseminated mycoses.20 Blastomycosis, coccidiomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis are the most common diseases (eFigs. 4.6 to 4.9). Cases have also been reported of histoplasmosis, paracoccidiomycosis, aspergillosis, and candidiasis of the prostate. The histology in these cases is identical to that seen in nonprostatic sites.21–25

MYCOBACTERIAL PROSTATITIS

Mycobacterial prostatitis may occur in patients with systemic tuberculosis, but today it is more commonly seen as a complication of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy for superficial bladder carcinoma.

The incidence of prostatic involvement in systemic tuberculosis ranges from 3% to 12%; in over 90% of these cases, there is coexisting pulmonary tuberculosis. In patients with urogenital tuberculosis, the prostate is involved in 75% to 95% of the cases.26,27 However, in only 7% to 13% of cases of urogenital tuberculosis is the prostate the sole organ involved. Most cases of tuberculous prostatitis appear to arise from hematogenous dissemination rather than contact with infected urine. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the prostate are exceedingly rare.28,29

Chuang et al.30 recently reported the rare occurrence of granulomatous prostatitis due to Mycobacterium abscessus in five patients who experienced poor wound healing following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. M. abscessus was cultured from the debridement specimens, and acid-fast–positive bacilli were identified histologically within the prostates. The authors further identified seven additional radical prostatectomy specimens with M. abscessus granulomatous prostatitis. Morphologically, suppurative necrotizing granulomatous inflammation extensively involved the prostate and frequently the extraprostatic soft tissue, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens. In addition to prolonged wound healing, urethrorectal fistula formation and pelvic abscess were encountered.30

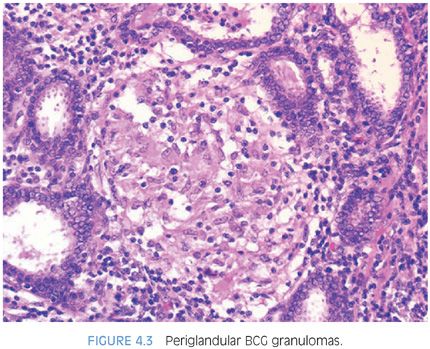

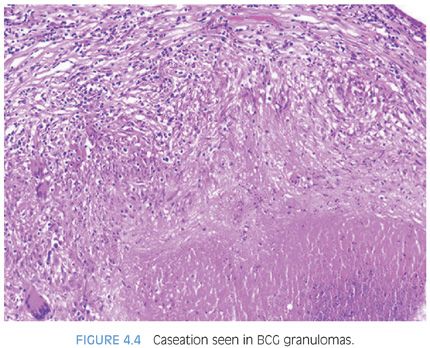

Following BCG immunotherapy for superficial bladder carcinoma, patients may have fever, mild hematuria, and urinary frequency. Approximately 40% of these men have an abnormal digital rectal exam and 55% have ultrasonographic abnormalities of the prostate.31–33 These lesions may further mimic carcinoma on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging34–36 and by elevating serum PSA levels. Following BCG, biopsies show caseating or noncaseating granulomas in 22% of cases and acid-fast stains are positive in approximately 50% of these cases. Histologically, the findings in BCG prostatitis are indistinguishable from those of tuberculous prostatitis occurring as a result of systemic infection. Small noncaseating granulomas are found in the periglandular stroma, as seen in early hematogenous dissemination of systemic tuberculosis (Fig. 4.3, eFig. 4.10). As these granulomas enlarge, they may eventually destroy glands (eFig. 4.11). There also may be large granulomas with caseous necrosis, consisting of grumous fine granular debris, as opposed to coagulative necrosis seen in postbiopsy resection granulomas (eFigs. 4.12 and 4.13). Large caseating granulomas predominate within the peripheral zone of the prostate, although the transition zone or central zone may also be involved (Fig. 4.4). In addition to the more peripherally located caseating and noncaseating granulomas, there are almost always small suburethral granulomas. In some instances, the suburethral granulomas are well-formed and discrete, and in other cases, more ill-defined granulomatous inflammation is seen. Regardless of the histologic pattern of BCG-related granulomatous prostatitis or the presence of acid-fast bacilli on special stains, patients are usually asymptomatic and require no specific therapy.31,32 It is not necessary in a man with a history of BCG therapy to perform stains for acid-fast organisms to evaluate prostatic granulomas; it is debatable whether stains for fungi should be done for completeness. Rarely, patients develop disseminated infection with BCG, accompanied by systemic signs and symptoms.

NONSPECIFIC GRANULOMATOUS PROSTATITIS

The most commonly diagnosed granulomatous process within the prostate is nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis. In a study of 25,387 benign prostate specimens, the incidence of nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis was 0.5%.18 Lesions occurred over broad ages ranging from 18 to 86 years of age with a mean and median age of 62 years. Common symptoms included irritative voiding symptoms (50%), fever (46%), chills (44%), and obstructive voiding symptoms (32%). In 82% of men, there was pyuria, and in 46% there was hematuria. Seventy-one percent of men experienced a urinary tract infection at an average of 4 weeks prior to diagnosis. In 59% of the men, the rectal exam revealed an indurated prostate suspicious for adenocarcinoma. The etiology of this lesion is thought to be a reaction to bacterial toxins, cell debris, and secretions spilling into the stroma from blocked ducts.

Nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis mimics prostate carcinoma on rectal exam ultrasound and MRI exams34,37 and can result in an elevated serum PSA level. At the same time, the pathologist could be confronted with a biopsy where the histology may closely mimic carcinoma38,39 (see Chapter 7).

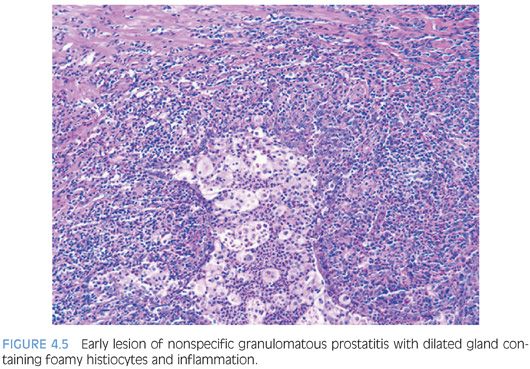

The earliest lesion in nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis consists of dilated ducts and acini filled with neutrophils, debris, foamy histiocytes, and desquamated epithelial cells (Fig. 4.5, eFigs. 4.14 and 4.15). Rupture of these ducts and acini results in a localized granulomatous and chronic inflammatory reaction (eFig. 4.16). Extension of the infiltrate into surrounding ductal and acinar units gives rise to the characteristic lobular dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes typical of more advanced nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis (Fig. 4.6, eFigs. 4.17 to 4.19). Many of the histiocytes have foamy cytoplasm and some are multinucleated. Neutrophils and eosinophils make up a smaller component of the inflammatory infiltrate. Often within the center of these large inflammatory nodules are dilated and partially effaced acini. Older lesions of nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis show a more prominent fibrous component.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree