Part 5 Head and brain

Bones

The skull

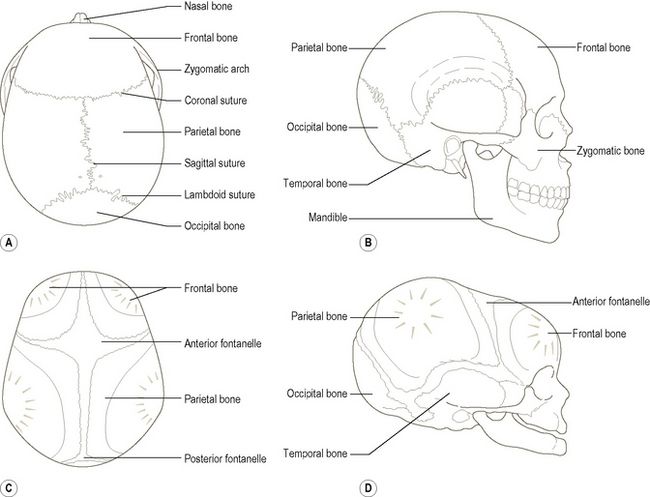

The cranial cavity of the human skull is relatively large, and projects anteriorly over the facial skeleton (Fig. 5.1). Its walls are composed of plates of bone arranged as two layers of compact bone enclosing a central layer of cancellous bone. These bones ossify in the membrane (intramembranous ossification) and are joined edge to edge by fibrous interlocking joints known as sutures (p. 17).

The top and most of the sides of the skull are formed by the two large parietal bones, which articulate along their medial borders at the sagittal suture (Fig. 5.1A). Anteriorly the skull is formed by the frontal bone, which joins the two parietal bones at the coronal suture. The point where the coronal and sagittal sutures meet is termed the bregma. At birth, the region of the bregma is not ossified and appears as an easily felt diamond-shaped area of connective tissue known as the anterior fontanelle. This gap gradually decreases in size and closes about 18 months after birth.

Growth of the skull

At birth the cranial cavity is relatively large but the face is small (Fig. 5.1D), being approximately one-eighth of the whole skull compared with one-third in the adult. The teeth are not fully formed and the paranasal sinuses are rudimentary, consequently both the jaws and nasal cavities are small. The individual bones are joined by cartilage; ossification progressing with age. There is no mastoid process so the styloid process and the stylomastoid foramen are closer to the side of the head. Undue pressure applied during a forceps delivery in the region of the developing mastoid may therefore damage the facial nerve. The maxilla is shallow because it has no sinus, and consists mainly of alveolar processes and developing teeth. The nasal bones are flat, so that the infant has no bridge to the nose, which together with the absence of superciliary arches gives the forehead its prominent appearance. The orbits are relatively large and have the nasal cavity lying almost completely between them.

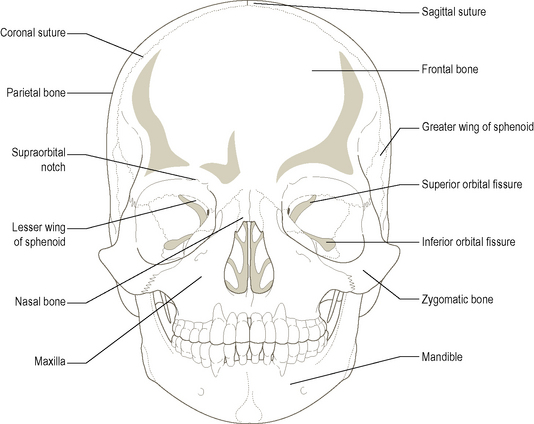

The skull viewed anteriorly

When viewed from the front (Fig. 5.2) the upper third of the skull consists of the cranial cavity and is formed by the frontal bone; this is the forehead. Parts of the parietal, sphenoid and temporal bones can also be seen in this region. Below the forehead are the two large orbital cavities, whose margins are formed by the frontal bone above, the zygomatic bone inferolaterally and the maxilla inferomedially. The walls of the orbital cavity are formed by the maxilla inferiorly, the zygomatic bone and greater wing of the sphenoid laterally, the frontal bone and the lesser wing of the sphenoid superiorly, and the ethmoid and lacrimal bones medially. Deep within the cavity can be seen the superior and inferior orbital fissures and the optic canal. Along the medial part of the superior margin is the supraorbital notch, transmitting the corresponding vessels and nerves. Towards the front of the medial wall is the opening for the nasolacrimal duct, which conveys secretions from the eye (i.e. tears) to the nose for eventual swallowing. Below the inferior orbital margin on the front of the face is the large infraorbital foramen, through which pass the infraorbital nerve and vessels onto the face.

The skull viewed from the lateral side

The temporal bone is central to the lateral aspect of the skull (Fig. 5.1B). Above it joins the parietal bone posteriorly and the greater wing of the sphenoid anteriorly, while posteroinferiorly it joins the occipital bone. It is marked just behind and below its centre by the external acoustic meatus, above which is a bony ramus passing forwards to meet a similar backwardly projecting process from the zygomatic bone to form the zygomatic arch. Just below the posterior part of this arch the mandibular fossa can be seen. The styloid process is seen projecting downwards from deep to the external acoustic meatus.

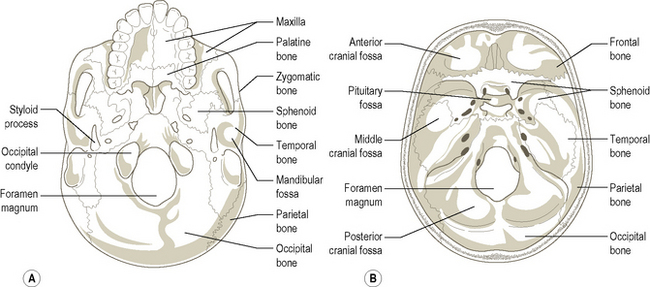

The skull viewed inferiorly

The skeleton of the face attaches to the undersurface of the anterior half of the cranial cavity. Consequently, a view from below reveals the mandible, maxilla and palatine bones. With the mandible removed the maxilla and the palatine bones can be clearly seen (Fig. 5.3A).

The central section of the undersurface of the skull is formed mainly by the sphenoid with its many bony processes and the foramina. Laterally lies the temporal bone marked by the mandibular fossa which receives the condyle of the mandible. Posterolaterally is the external acoustic meatus, while posteromedially is the styloid process of the temporal bone – a long and slender projection passing downwards and anteromedially (Fig. 5.3A). Medial to the styloid process anteriorly is the carotid canal and posteriorly the jugular foramen.

The floor of the cranial cavity

The floor of the cranial cavity is formed by the base of the skull, with both the right and left sides having similar features (Fig. 5.3B). The two halves are divided in the sagittal plane by the crista galli anteriorly, the body of the sphenoid centrally, and the foramen magnum and internal occipital protuberance posteriorly. The floor is further divided into anterior, middle and posterior cranial fossae by prominent ridges of bone, with each fossa lying at a different level, the posterior being at the lowest level and the anterior the highest.

Anterior cranial fossa

This lies above and in front of the middle cranial fossa (Fig. 5.3B), being separated from it by the posterior concave edge of the lesser wings of the sphenoid. It contains the lower part of the frontal lobes of the brain. The walls and most of the floor of the fossa are formed by the frontal bone, with the posterior part of the floor being formed by the lesser wings of the sphenoid. Between the two sides is a sagittally directed elongated hollow. Running centrally in this hollow is a crest known as the crista galli on either side of which is a perforated horizontal plate, the cribriform plate. It is through this plate that the olfactory nerves from the upper part of the nasal cavity pass to the olfactory bulb above the cribriform plate.

Middle cranial fossa

This lies behind and below the anterior cranial fossa (Fig. 5.3B), being formed by the temporal and sphenoid bones. It consists of a median and two lateral parts. The lateral parts contain the temporal lobes of the brain, while the raised median part is formed by the body of the sphenoid. Passing laterally from the body of the sphenoid are the greater wings of the sphenoid, which, together with the squamous part of the temporal bone, turn superiorly, forming the lateral wall of the skull in the temporal region. The floor of the middle cranial fossa is formed by part of the greater wings of the sphenoid anteriorly and the gently sloping superior surface of the petrous part of the temporal bone posteriorly. Anteriorly each greater wing of the sphenoid turns upwards forming the anterior wall of the fossa. The superior part of this wall is overlapped by the posterior edge of the anterior cranial fossa, i.e. the lesser wings of the sphenoid.

The body of the sphenoid has a smooth, hollowed depression superiorly, the pituitary (hypophyseal) fossa, in which sits the pituitary gland. Small horn-like (clinoid) processes project on either side from the front and back of the hollow. They give attachment anteriorly to a horizontal fold of the dura mater (the tentorium cerebelli) which passes between the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres. The cavernous sinuses (p. 591), part of the intracranial venous sinus system, are formed between the two layers of the dura mater either side of the body of the sphenoid. Within the walls, or through these sinuses, pass many of the nerves destined for the orbit, as well as the internal carotid artery. The internal carotid artery emerges from the sinus anterolateral to the anterior clinoid process. Anterior to this region, between the roots of the lesser wings of the sphenoid, is the optic canal running forwards and laterally conveying the optic nerve and ophthalmic artery to the orbit. Passing transversely between the two optic canals is a groove called the sulcus chiasmatis; it does not lodge the optic chiasma. Between the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid is a gap which becomes narrower as it passes laterally. This is the superior orbital fissure and opens directly into the back of the orbit. It transmits many structures to and from the orbit – the third, fourth, ophthalmic division of the fifth, and sixth cranial nerves, and the ophthalmic veins. Below the superior orbital fissure in the anterior wall of the middle cranial fossa close to the body of the sphenoid is the rounded foramen rotundum, through which passes the maxillary division of the fifth cranial nerve into the pterygopalatine fossa.

Posterior cranial fossa

The largest and deepest of all three fossae (Fig. 5.3B); in it lodges the cerebellum. The temporal bone is seen as a hard ridge passing backwards and laterally from the body of the sphenoid. Along its superior border runs a longitudinal groove for the superior petrosal sinus.

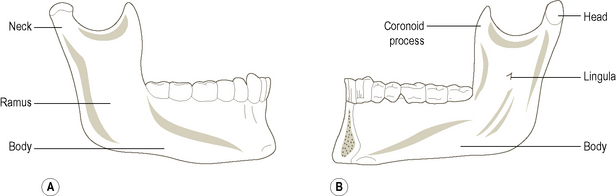

The mandible

The mandible (Fig. 5.4) or lower jaw completes the skull. It consists of a horizontal convex body, with two upwardly projecting rami from the posterior ends of the body. The rami and body all present an outer and an inner surface, with the body having superior and inferior borders, while the rami have anterior and posterior borders. The outer surface of the body is slightly concave from top to bottom and markedly convex from side to side, and may show a vertical line in the midline where the two halves have fused. Towards the front of the body on each side is the mental foramen transmitting the mental nerve and vessels. The inner surface of the body is divided by a slightly raised ridge of bone, the mylohyoid line, into upper and lower areas. Behind the front of the mandible, above this line, is the sublingual fossa which lodges the sublingual salivary gland, while below this line, in the middle third of the body, is the submandibular fossa for the submandibular gland. On the inner surface of the anterior midline region are two pairs of bony projections, the genial (mental) spines. The upper pair lie above the mylohyoid line and give rise to part of the tongue (genioglossus), while the lower pair lie below the line and give attachment to geniohyoid. The superior border of the body consists of a series of sockets for the teeth. The bone behind the third molar is thickened as it joins the anterior border of the ramus. The lower border of the body is thick and rounded, but shows two fossae anteriorly, one each side of the midline. These are the digastric fossae, each giving attachment to the anterior belly of digastric. Posteriorly the body meets the lower posterior part of the ramus at the angle, which tends to be everted in males and inverted in females. Just in front of the angle the lower border is notched where the facial artery crosses it to enter the face.

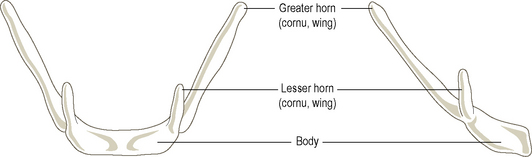

The hyoid bone

The U-shaped hyoid bone (Fig. 5.5) is deficient posteriorly and suspended in the neck by muscle attachments below the tongue and above the larynx (see Fig. 5.8). Being attached to the tongue, it moves up and down with the tongue during swallowing. Because the hyoid is also firmly attached to the larynx by the thyrohyoid membrane, when the hyoid moves upwards it carries the larynx with it. The hyoid consists of a body anteriorly, a pair of greater horns which project upwards and backwards from the body, and a pair of lesser horns which also project upwards and backwards from the junction of the body with the greater horns. The lesser horns and upper part of the body of the hyoid are derived from the second pharyngeal arch, while the greater horns and lower part of the body are from the third pharyngeal arch. The stylohyoid ligament, also from the second arch, attaches to the lesser horn. The hyoid is connected by muscles and ligaments to the tongue, the mandible, base of the skull (styloid process), thyroid cartilage and sternum.

Muscles

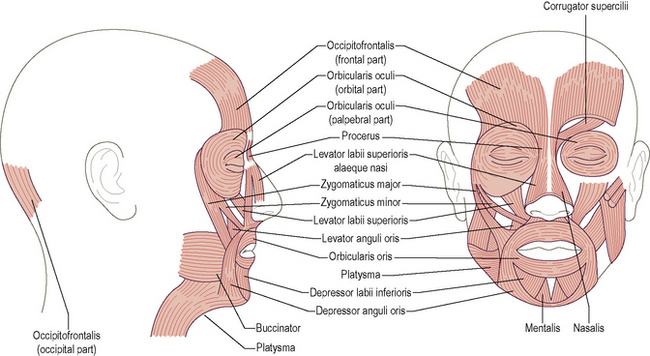

Muscles which change the shape of the face

The muscles which change the shape of the face are commonly known as the muscles of facial expression (Fig. 5.6). Although with the contraction of individual or groups of muscles, human beings can smile, frown, look happy or sad, and generally convey many emotions, it must be remembered that the primary action of the majority of these muscles is to dilate (open) or constrict (close) the eyes, nose and mouth. In addition, one of these muscles, buccinator, plays an important role in mastication (p. 552), while others are involved in forming and shaping the sounds produced by the larynx into recognizable words.

Movements of the eyebrows

Occipitofrontalis

Raising the eyebrows, as in an expression of surprise, is produced by occipitofrontalis (Fig. 5.6), which is in two parts united by the strong aponeurosis of the scalp. The posterior part arises from the outer part of the superior nuchal line and the mastoid part of the temporal bone from where it passes to attach to the aponeurosis. The larger anterior part of the muscle runs from the aponeurosis to the superficial fascia of the forehead and eyebrow, interlacing with orbicularis oculi.

Corrugator supercilii

This small muscle (Fig. 5.6) arises from the medial end of the superciliary arch (eyebrow), blending with orbicularis oculi. Its fibres run upwards and laterally to attach to the skin of the eyebrows. On contraction they pull the two eyebrows together medially and downwards as in a frown, so producing the deep vertical wrinkles between the eyebrows.

Procerus

These small muscles, are continuous with each other across the midline. They run from the lower part of the nasal bone to the skin over the lower part of the forehead, intermingling with the anterior belly of occipitofrontalis (Fig. 5.6). On contraction they pull down the medial part of the eyebrow producing transverse wrinkles at the root of the nose.

Muscles around the eye

Orbicularis oculi

One of the most complex muscles of the face and by far the most important around the eye (Fig. 5.6). It consists of three parts – an orbital part, a palpebral part and a lacrimal part. The orbital part surrounds the orbit, spreading onto the forehead, temple and cheek, taking its origin from the medial margin of the orbit and the medial palpebral ligament. The fibres arising from above the ligament run elliptically around the orbit to attach again below the ligament.

Muscles around the nose

These small muscles around the nose (Fig. 5.6) act to dilate or constrict the nasal apertures. These actions are rudimentary in humans, but are of obvious importance in some animals, for example, camels. The dilators are nasalis and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, which also acts on the upper lip, while the constrictor is depressor septi.

Muscles around the mouth

Orbicularis oris

Surrounding the mouth (Fig. 5.6) orbicularis oris is a composite sphincter muscle with deep and superficial parts. Vertically it extends from the nasal septum to midway between the chin and lower lip. The deep fibres are continuous with buccinator, while the superficial fibres are all derived from other muscles. The deep fibres attach to both the maxilla and mandible near the lateral incisor. Between the deep and superficial layers of the muscle, the intrinsic fibres of orbicularis oris run elliptically around the mouth, having no bony attachment. Some of the superficial fibres decussate like those of buccinator.

Buccinator

Buccinator is continuous with the deep part of orbicularis oris and forms the substance of the cheek (Fig. 5.6). It arises from both the maxilla and the mandible opposite the molar teeth, and from the pterygomandibular raphe, which stretches from the pterygoid hamulus to the posterior end of the mylohyoid line. The fibres run forwards to blend with those of orbicularis oris. The medial fibres decussate posterolateral to the angle of the mouth, so that the lower fibres run to the upper lip and the upper fibres to the lower lip. The interlacing of deep buccinator fibres, with some of the superficial fibres of orbicularis oris, forms an easily felt nodule at the angle of the mouth known as the modiolus.

Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi

This muscle (Fig. 5.6) arises from the maxilla and attaches to the ala of the nose and skin, and the muscle of the upper lip.

Levator labii superioris

This muscle (Fig. 5.6) arises from the maxilla above the infraorbital foramen and attaches to the upper lip towards its lateral end.

Zygomaticus major and minor

These both arise from the zygomatic bone and attach to the upper lip near its angle (Fig. 5.6).

Levator anguli oris

This arises from the maxilla below the infraorbital foramen (Fig. 5.6), inserting into skin and muscle at the angle of the mouth. A few of its fibres may pass to the lower lip.

Depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris

Depressor anguli oris arises from the front of the mandible below the mental foramen and blends with the muscles of the lower lip at the angle of the mouth (Fig. 5.6), as well as inserting into skin. Some of its fibres may pass into the upper lip. It is continuous with platysma and overlaps depressor labii inferioris which also arises from the mandible below the mental foramen. Its fibres attach to the skin and muscle of the lower lip, the fibres from each side blending together (Fig. 5.6).

Risorius and mentalis

These two muscles, risorius and mentalis although considered as part of the lower lip musculature, usually only have connections to the skin of the lower lip. Risorius arises from the fascial covering of the parotid gland and inserts into skin at the angle of the mouth. Mentalis arises from the mandible below the incisors and passes to the skin of the chin (Fig. 5.6). Platysma (Fig. 5.6), with which risorius may be completely fused, is considered later (p. 557).

Muscles moving the mandible

The movements of the mandible are complex, involving the coordinated action of the muscles attached to it. Because of the nature of the temporomandibular joint (p. 559), four basic movements of the mandible can be identified; these being:

Muscles elevating the mandible

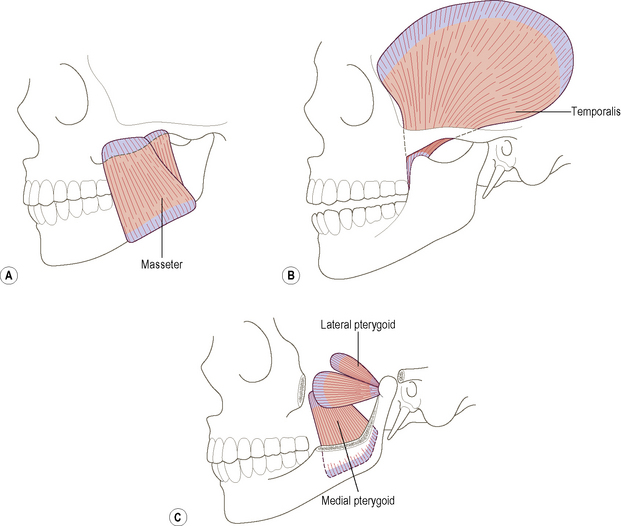

Masseter

A flat quadrilateral muscle with deep and superficial parts (Fig. 5.7A). The superficial part arises from the zygomatic process of the maxilla and the anterior two-thirds of the zygomatic arch, the muscle fibres running downwards and backwards to attach to the outer surface of the angle of the mandible, extending onto the lower half of the outer surface of the ramus. The deeper part arises from the deep surface of the zygomatic arch, the fibres of which run downwards and backwards to attach to the ramus and coronoid process of the mandible.

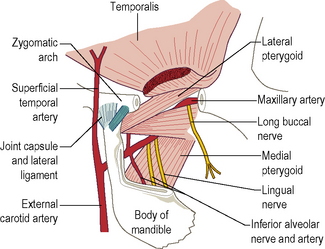

Medial pterygoid

A thick quadrilateral muscle (Fig. 5.7C; see also Fig. 5.14) arising from the medial side of the lateral pterygoid plate and the pyramidal process of the palatine bone. A smaller head arises from the maxillary tubercle. From these two origins, which surround the lower fibres of lateral pterygoid, the muscle fibres run downwards, backwards and laterally to attach to a rough triangular impression on the inner surface of the mandible between the angle and the mylohyoid line.

Muscles retracting the mandible

Temporalis

A large, flat, fan-shaped muscle arising from the temporal fossa of the temporal bone and the fascia covering it (Fig. 5.7B). The anterior fibres run almost vertically, while the most posterior are almost horizontal. All of the muscle fibres, however, converge to a thick tendon which passes deep to the zygomatic arch to insert into the apex and deep surface of the coronoid process and anterior border of the ramus of the mandible. A few fibres may become continuous with buccinator, while other more superficial fibres may fuse with masseter.

Muscles protracting the mandible

Lateral pterygoid

The lateral pterygoid (Fig. 5.7C; see also Fig. 5.14) has two heads, an upper head which arises from the inferior surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid, and a lower head which arises from the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate. From this extensive origin the fibres pass backwards and slightly laterally to insert into the front of the neck of the mandible and the capsule and intra-articular disc of the temporomandibular joint.

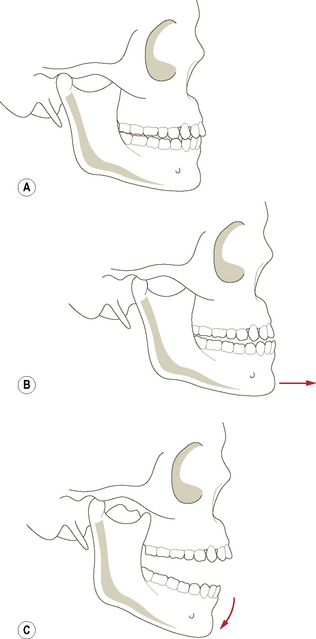

Action

Contraction of lateral pterygoid pulls the head of the mandible, the intra-articular disc and the joint capsule forwards onto the articular eminence – a movement which occurs during protraction of the mandible and opening the mouth. Working with medial pterygoid of the same side, lateral pterygoid produces a slight rotation of the jaw so that the chin swings to the opposite side. When all four pterygoid muscles contract, the mandible is protruded so that the lower incisors are carried in front of the upper ones (see Fig. 5.16B). When only both lateral pterygoids are working, the head of the mandible is carried forwards; there is an accompanying slight rotation of the head against the intra-articular disc so that the mouth opens. This is essentially what happens when sleeping with the mouth open. Lateral pterygoid is the main antagonist to retraction; its eccentric contraction therefore helps to control this movement.

Muscles depressing the mandible

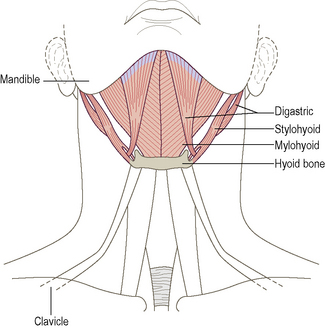

Digastric

Digastric as its name suggests, has two bellies, anterior and posterior, united by an intermediate tendon (Fig. 5.8). The posterior belly passes downwards and forwards from the medial surface of the mastoid process in close association with stylohyoid, to an intermediate tendon which passes through the insertion of stylohyoid and is held by an aponeurotic sling to the upper surface of the hyoid. The anterior belly of the muscle runs upwards and forwards to attach to the digastric fossa on the lower border of the mandible close to the symphysis menti.

Mylohyoid

The mylohyoid (Fig. 5.8) arises from the mylohyoid line on the inner surface of the body of the mandible. Its fibres run downwards and medially towards the midline to insert into a median fibrous raphe which extends from the symphysis menti to the upper surface of the body of the hyoid bone. The two mylohyoid muscles thus give rise to a muscular sheet which forms the floor of the mouth.