15 Breast

ANATOMY

DEVELOPMENT AND FORM

Glandular structure

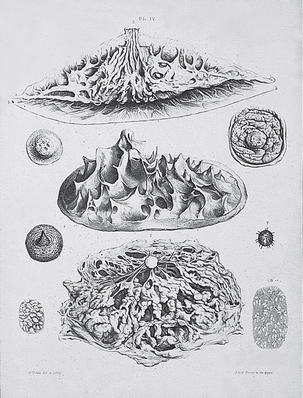

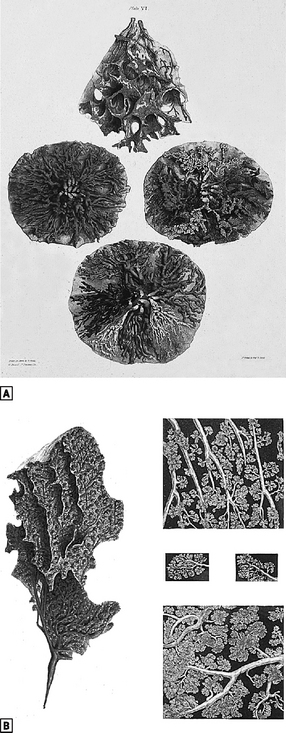

The breast is a glandular structure lying within the superficial fascia of the anterior chest wall. This disc shaped mass of tissue is composed of epithelial parenchyma together with supporting connective tissue. The breast is essentially a conglomerate gland consisting of 15–20 lobes which are pyramids of glandular tissue with an apex pointing towards the nipple and a base peripherally. Secretions drain centripetally towards the nipple and each lobe drains via a system of branching ducts into a lactiferous sinus and in turn into a collecting duct which opens at the tip of the nipple. Each lobe drains separately and there is no communication between the ducts of adjacent lobes (Fig. 15.1). Individual lobes are composed of tubuloalveolar structures in which several acini or alveoli open into a common duct – the terminal duct. This combination of glandular acini together with their draining duct is termed the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU) and represents the basic functional unit of the breast. The terminal ducts drain into subsegmental and in turn larger segmental ducts which are interwoven within any single lobe. The epithelial elements are supported by connective tissue which surrounds the gland and extends as collagenous and inelastic septa between the lobes and lobules. This was formerly known as the ‘fascia mammae’ which is derived from fibrous tissue in the subcutaneous layer of the chest wall and does not constitute a true capsule. However, it forms the basis for the suspensory mechanism of the breast by its attachment to the periosteum of the ribs and the skin anteriorly. The deeper layer of the superficial fascia covers the posterior surface of the breast and forms the anterior wall of the retromammary bursa. The more superficial layer of ‘fascia mammae’ extends over the anterior of the gland and penetrates the substance of the organ to provide support for both glandular and ductal elements. Fibrous thickenings formed of collagenous bundles pass from the superficial mammary fascia to the dermis of the skin. These suspensory ligaments of Astley Cooper form projections which spread out to form a white, firm irregular surface of folds between the skin and the glandular tissue (Fig. 15.2). They permit considerable mobility of the breasts in addition to a supportive function.

Blood supply

Despite its importance as an organ of lactation, the breast does not have a blood supply from a single defined source. Perforating branches of the internal mammary artery pierce the 2nd, 3rd, 4th (and occasionally 5th) intercostals spaces and traverse the pectoralis major muscle to supply the medial and deep parts of the gland. These vessels can produce troublesome bleeding at operation should they retract into the chest wall once divided. These branches anastomose with those of vessels entering from the superolateral aspect of the breast arising from the axillary artery; the lateral thor-acic artery provides branches which sweep around the lateral border of pectoralis major to reach the gland. Branches from the thoracoacromial trunk together with some intercostals vessels supply the deeper aspects of the gland. There is a rich anastomotic network between these different sources of blood supply and during pregnancy the medial perforators increase consid-erably in diameter.

Lymphatic drainage

Axillary nodes

Lymphatic vessels

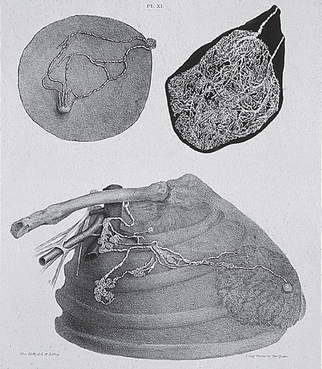

The lymphatic system of the breast is a complex network of arborising vessels which reflect its embryological origin from anterior thoracic wall structures. The lymphatics of the breast skin and parenchyma are inter-connected and flow within the valveless vessels is passive. This results in a degree of plasticity which isrelevant to malignant infiltration whereby uni-directionallymph flow may be diverted due to blockage at prox-imal sites by tumour emboli. The lymphatics of the skin of the breast represent part of the superficialsystem of the neck, thorax and abdomen. In the region of the NAC, a cutaneous plexus is linked to a subareolar plexus which receives lymphatics from the glandular tissue of the breast. From this subareolar and a related circumareolar plexus, lymph flows principally to the axillary nodes via a lateral lymphatic trunk. This together with the minor inferior and medial lymph-atic trunks drain along the surface of the breast to penetrate the cribriform fascia and reach the various groups of axillary nodes (Fig. 15.3). Anatomical studies suggest that the lymphatics of the breast initially drain to a group of 3–5 ‘sentinel’ nodes usually located at level I. Lymphatic channels exist which bypass the lower axillary nodes and probably account for ‘skip’ metastases and the finite false negative rate of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Lymph drains medially from the circumareolar plexus into lymphatics accompanying the internal mammary vessels to enter the internal mammary (parasternal) nodes. Approximately 75% of lymph flow passes to the axillary nodes and 25% to the internal mammary nodes.

PHYSIOLOGY

DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION

Breasts are functionally dynamic organs whose activity is controlled by a variety of hormones and chem-ical modulators. Some of these directly influence physiological processes whilst others act in a permissive capacity, but collectively they are important for breast development, secretion (lactogenesis) and milk production (galactopoiesis). Oestrogen promotes duct elongation and branching as well as fat deposition; progesterone governs lobule development and establishes the secretory state. The two hormones act synergistically to co-ordinate breast development. During pregnancy, the alveoli further develop under the influence of prolactin which triggers milk production and release after parturition.

PUBERTY

In the female at puberty, breast tissue is stimulated by oestradiol which is secreted by the ovary after follicular maturation induced by follicle stimulating and luteinizing hormones. These gonadotrophins are released from the pituitary in response to hypothalamic gon-adotrophin-releasing hormone. Breast epithelium is initially stimulated by oestrogen only (oestradiol) which results in ductal growth and branching. Development of the functional unit of the breast (TDLU) occurs after ovulation when progesterone is released from the corpus luteum. This together with an increase in the supporting periductal connective tissue leads to lobular development and attainment of the mature breast in size, form and shape.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree