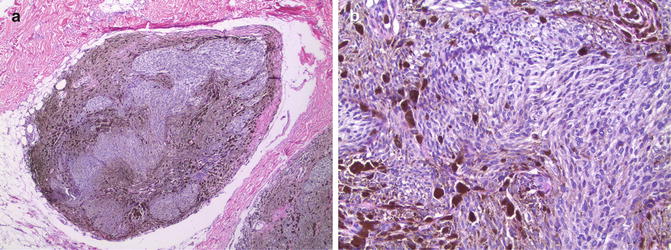

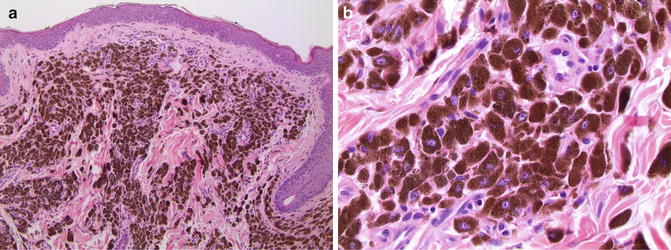

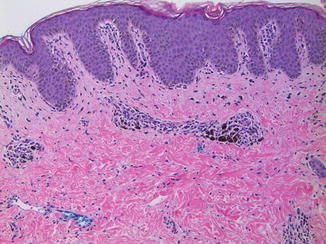

Fig. 10.1

Blue nevus. (a) Pigmented fusiform and dendritic cells between thickened collagen fibers (×10). (b) Note the delicate branched dendritic processes (×40)

Cellular Blue Nevus

The cellular variant of blue nevus contains aggregates of melanocytes with either a fusiform or small epithelioid morphology arranged into elongated nests or fascicles [1, 10]. The nests may concentrate in the adventitial dermis surrounding adnexal structures or in a perivascular or perineural distribution. These fascicular collections of melanocytes may protrude into the underlying subcutis producing a plexiform or “dumbbell” shaped lesion (Fig. 10.2). The nests are surrounded by more heavily pigmented melanophages. Pigmented fusiform and dendritic cells typical of ordinary blue nevus are present in variable numbers, often more peripherally distributed in the lesion. Most lesions lack significant cytologic atypia and have few mitotic figures. Atypia, when present, may present a diagnostic challenge [11]. Cytogenetic aberrations have been documented in lesions with significant cytologic atypia and with high mitotic rates [12]. So-called “ancient changes” also have been reported in cellular blue nevi, but these features do not affect the benign clinical behavior [13].

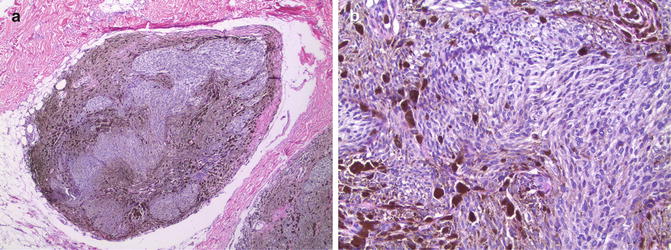

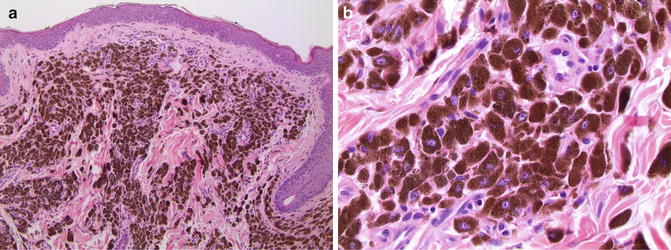

Fig. 10.2

Cellular blue nevus. (a) Elongated nests of fusiform and epithelioid cells in a plexiform pattern extending into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (×4). (b) Most of the cells have a fusiform or small epithelioid appearance and contain finely granular cytoplasmic melanin. Note the more heavily pigmented melanophages toward the periphery of the nests (×20)

Deep Penetrating Nevus

The deep penetrating nevus has microscopic features that overlap ordinary blue nevus, cellular blue nevus, and spindle and epithelioid cell (Spitz) nevus [5–7]. Similar to cellular blue nevus, the less-pigmented spindle and epithelioid cells toward the base of the lesion may concentrate around blood vessels and nerves producing a plexiform pattern of growth reminiscent of a neurofibroma (Fig. 10.3). Deep penetrating nevus also has been described as a component of a combined nevus [5, 8, 9].

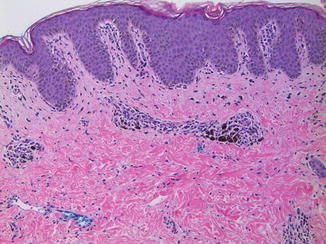

Fig. 10.3

Deep penetrating nevus. (a) Superficial portion of the lesion with elongated nests of fusiform cells surrounded by more heavily pigmented melanophages (×4). (b) Deeper portion of the lesion with melanocytes following adnexal structures and nerves (×10)

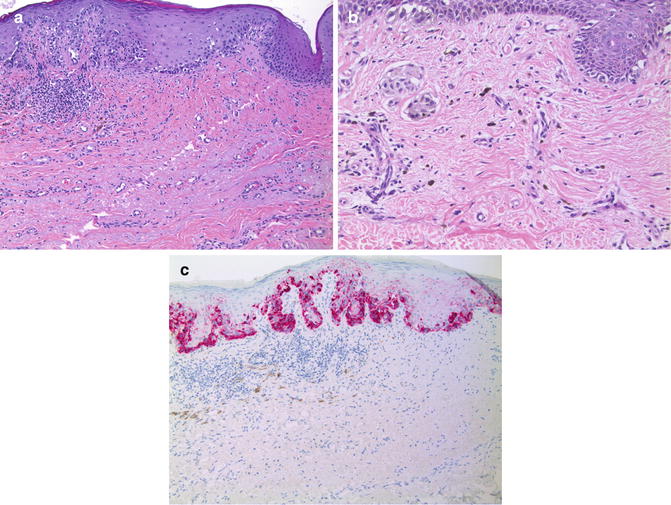

Immunohistochemical Features

The Immunohistochemical features are similar for each of the variants of blue nevus. As would be expected for cells having abundant cytoplasmic melanin, labeling for melanosomal glycoproteins such as gp100 (using HMB-45) is present (Fig. 10.4) [10, 14, 15]. Interpretation of Immunohistochemical markers of melanosomal proteins is facilitated by use of a red chromogenic substrate to avoid interference with brown cytoplasmic melanin. Labeling typically is uniform throughout the nevus including the melanocytes toward the base. The pattern of maturation typical of an ordinary acquired compound or intradermal nevus having diminished expression with progressive dermal descent (see Chap. 4) is not observed. Labeling for Ki-67 antigen (MIB-1) is not increased (Fig. 10.4) [15].

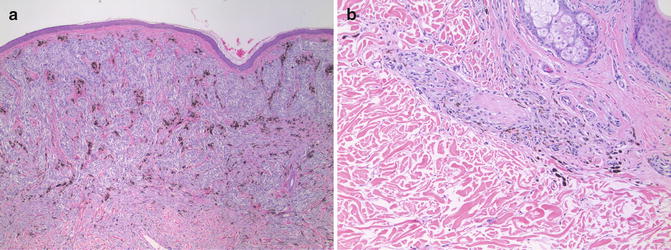

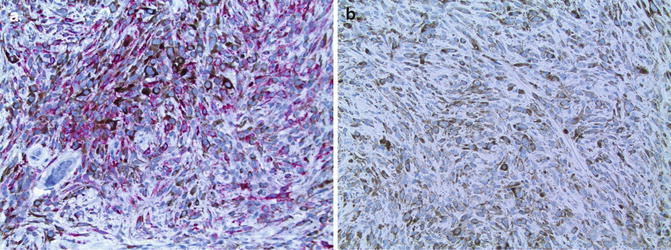

Fig. 10.4

Immunohistochemistry of cellular blue nevus. (a) Prominent labeling for gp100 (using HMB45) by most of the fusiform and small epithelioid melanocytes (×20). (b) Very few of the melanocytes display nuclear labeling for Ki-67 (using MIB-1) (×20)

Pigmented Epithelioid Melanocytoma

Clinical Features

The appellation pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma (PEM) was recently proposed for a lesion that has large epithelioid melanocytes with abundant cytoplasmic melanin [16]. Initially, PEM was proposed to include epithelioid blue nevi associated with Carney Complex (a syndrome characterized by lentigines, myxomas, schwannomas, and endocrine abnormalities) and possibly the pigment synthesizing “animal-type” melanoma, an often less biologically aggressive pigmented melanoma resembling lesions described in horses [17–19]. PEM occur as solitary, usually well-circumscribed nodular lesions with pigmentation similar to that of cellular blue nevi [20]. Although rare, most PEM are sporadic and are not associated with an underlying syndrome. Clinical follow-up suggests that most of these lesions have a benign clinical course, although local recurrence, regional lymph node metastasis, and rare cases of distant metastasis were reported [16, 21]. Recently, it was shown that the large epithelioid melanocytes in most PEM lack expression of one cAMP-dependent protein kinase A regulatory subunit isoform (PKA R1alpha) similar to that observed in the epithelioid blue nevi associated with the Carney Complex [22]. Loss of expression correlated with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the PKA R1alpha gene locus at 17q22–24, the same gene mutated in Carney Complex. Loss of expression of PKA R1alpha was not observed in several pigment synthesizing (animal-type) melanomas. This difference and the low rate of distant metastasis, suggest that PEM is a unique neoplasm of lower malignant potential.

Microscopic Features

PEM is characterized by intradermal collections of large epithelioid cells containing abundant cytoplasmic melanin (Fig. 10.5). The lesion may be hypercellular and contain areas in which the epithelioid cells are closely apposed, but not forming cohesive nests. Numerous melanophages are present within the lesion as well. The melanophages typically are smaller than the epithelioid melanocytes. Larger nodules may be ulcerated and some lesions have a small junctional component. Most of the epithelioid melanocytes have an enlarged nucleus with a single prominent nucleolus. Mitotic figures are rare, but if present, should raise suspicion for a more aggressive clinical course. In some PEM, cytoplasmic melanin may obscure the nucleus and obviate assessment of mitotic rate necessitating histochemical bleaching procedures. It is important to remember that subsequent immunohistochemical studies may be unreliable on sections previously bleached of melanin.

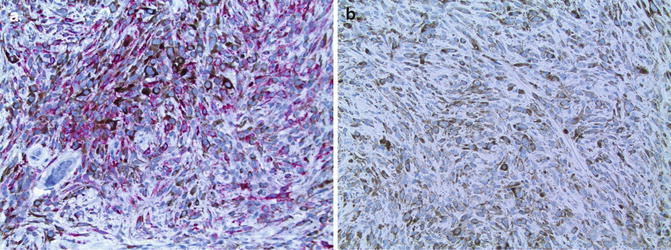

Fig. 10.5

Pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma. (a) Closely apposed large epithelioid melanocytes with abundant cytoplasmic melanin pill the upper dermis (×10). (b) Most of the cells have an enlarged nucleus containing one or two prominent eosinophilic nucleolus/nucleoli (×40)

Immunohistochemical Features

Similar to blue nevi, markers of melanosomal glycoproteins such as gp100, and Melan A/MART-1 are expressed in cells of PEM. Labeling for Ki-67 antigen may be useful to identify “hot spots” of proliferative activity not observed in cellular blue nevi. Loss of expression of PKA R1alpha can be documented by immunohistochemistry and LOH of 17q22–24 confirmed by molecular genetic analysis [22].

Differential Diagnosis: Post-Inflammatory Pigmentary Alteration (PIPA)

Clinical Features

Melanocytic lesions containing heavily pigmented dermal melanocytes must be distinguished from other neoplasms and inflammatory dermatoses rich in melanophages. Dermal aggregates of melanophages may elicit a clinical appearance similar to that of blue nevi. Any neoplasm or inflammatory dermatosis resulting in cytolysis of melanin-containing cells may lead to melanin incontinence and a subsequent infiltrate of melanophages [23, 24]. Epidermal keratinocytes provide the source of melanin incontinence for many of the inflammatory dermatoses associated with PIPA. Lichenoid interface dermatoses such as lichen planus or lupus erythematosus often result in areas of PIPA as does physical trauma such as chronic rubbing/excoriation or thermal injury.

Microscopic Features

The common finding in PIPA regardless of etiology is the presence of melanophages in the dermis (Fig. 10.6). Resolved inflammatory dermatoses may have few other inflammatory cells suggestive of an active process. Epidermal rete ridges may be attenuated in resolved lichenoid interface dermatitis and the basement membrane zone may be thickened in long-standing lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus. Individual melanophages have a small epithelioid appearance. Most contain coarse granular melanin and a small nucleus with inconspicuous nucleoli. Some melanophages may be elongated, but delicate branched dendritic processes are not present. This feature is critical for distinguishing PIPA from blue nevus. Similarly, melanophages are much smaller and lack the nuclear changes typical of the epithelioid cells in PEM.

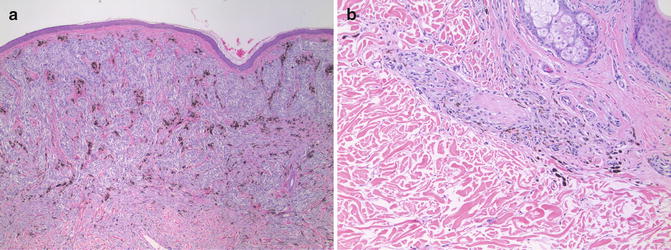

Fig. 10.6

Postinflammatory pigmentary alteration. Example of a partially resolved fixed drug eruption with clusters of melanophages in a perivascular distribution in the upper dermis (×10). The melanophages are small and lack dendritic processes or nuclear atypia

Differential Diagnosis: Regressed Malignant Melanoma

Clinical Features

Clinical history of a changing melanocytic lesion with asymmetry, irregular borders, and variation in color should raise suspicion of an atypical melanocytic nevus or malignant melanoma. Some melanomas and atypical nevi undergo spontaneous regression mediated by the host immune system. Clinical features of regression often are manifest by irregular areas of hypopigmentation/depigmentation, hyperpigmentation or erythema within a preexisting pigmented lesion. A melanocytic lesion undergoing spontaneous regression may exhibit multiple shades of blue, brown, black, and red or may have zones devoid of melanin. Long-standing regression may produce a depigmented/hypopigmented patch resembling a lesion of vitiligo or an old scar. Clinical knowledge of a prior pigmented lesion at the site may thus be necessary for accurate diagnosis.

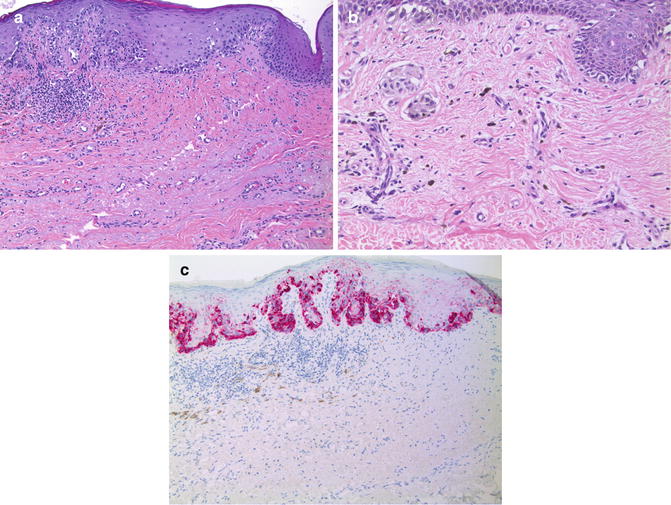

Microscopic Features

Many of the histologic features described for PIPA above also are present in regressed melanomas (Fig. 10.7) [25–27]. In fact, regression involves an immunoregulatory response that results in melanoma cell death and melanin incontinence with subsequent melanophage activity of variable degree. Other features suggestive of regression include alterations of dermal collagen fibers, vascular proliferation, and attenuation of overlying epidermal rete ridges, features also present in scars and recurrent nevi [28, 29]. Partially regressed lesions also contain residual melanoma cells in the epidermis and/or in the dermis in addition to the infiltrate of melanophages. Immunohistochemistry may be helpful to identify a small residual focus of melanoma partially obscured by the inflammation associated with regression. Histologic features suggestive of regression in the absence of a melanocytic lesion require adequate clinical correlation to determine if the biopsy is a representative sample of the lesion.

Fig. 10.7

Malignant melanoma with partial regression. (a) Melanoma in situ with features of regression in the subjacent dermis (×20). (b) Clusters of small epithelioid melanophages are scattered within an area of dermis having lamellar fibroplasia and vascular proliferation (×20). Note the nests of larger epithelioid invasive melanoma cells toward the left edge. (c) Anti-Melan A/MART-1 highlights the intraepidermal melanoma cells, but does not reveal a residual invasive dermal component (×20). Numerous small melanophages within the area of regression are not immunolabeled

Differential Diagnosis: Foreign Body Reaction to Tattoo

Clinical Features

Clinical history of prior trauma may be the best clue for the diagnosis of a foreign body tattoo. Pigmented material commonly found in traumatic tattoos include graphite, metals such as aluminum, and components of soil. Intentional (ornamental) tattoos also may be seen as an incidental finding in biopsies of an adjacent neoplastic or inflammatory process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree