Chapter Six Atomic structure

CHECK YOUR EXISTING KNOWLEDGE

Atomic theory

It is important to realize at the outset that the descriptions of atoms and atomic particles that you will encounter here and in other texts are merely models designed to help us understand how atoms behave and interact. As with any model, there is a degree of simplification – in the case of atomic modelling, this simplification is often so gross that the model bears no relationship to reality. Atoms are, pretty much, incomprehensible things: you can’t see them, even with the most powerful microscopes (you will learn why in Chapter 8); you can’t taste them, feel them, hear them; you can’t touch them, merely the fields that surround them.

The Thomson atom

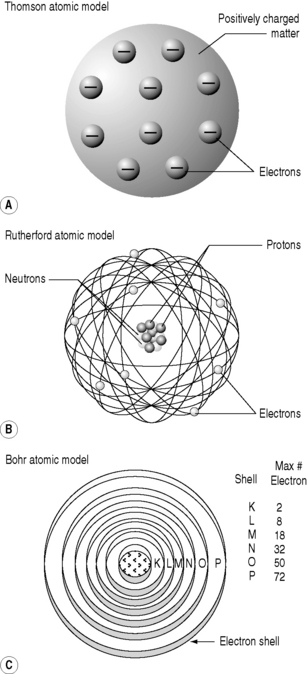

With J.J. Thomson’s 1898 discovery of electrons, and the realization that all atoms contained these particles, scientists had their first insight into the structure of the atoms. They knew that atoms were electrically neutral; therefore, there must be a positive charge balancing the negative charge of the electrons. This led to the ‘Thomson’ model of the atoms – also called the ‘plum-pudding’ model. In this scenario, the spherical atom of positively charged matter has electrons studded into it, like raisins in a plum, or Christmas, pudding (Fig. 6.2).

The Rutherford atom

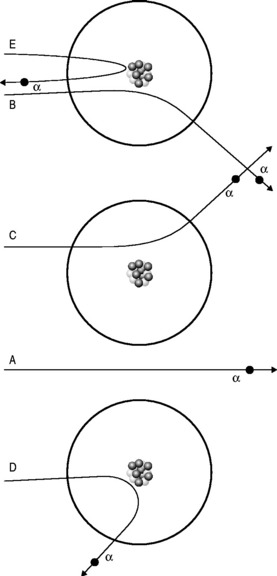

For some time, it had been known that α-particles could be slightly deflected when fired at thin sheets of metal foil. This was entirely consistent with the Thomson model of the electron with weak electric forces being exerted on the passing α-particles by the uniformly distributed charges of the ‘plum pudding’ atoms.

He realized that the only model that could account for the α-particles’ extraordinary behaviour was if the positive charge was all concentrated into a small, tightly bound, dense nucleus with the electrons more diffusely dispersed at a distance (Fig. 6.2). This alone could account for the findings: it would mean that much of apparently solid objects was empty space, which was why most of the α-particles passed through the foil without deviation. The light, widely separated electrons had little influence on the passage of the incoming particles but if they came within the electric field of the large, positive charge of the nucleus, they could be deflected or even repelled (Fig. 6.3). In fact, it transpires that 99.999999% of matter is empty space; if the nucleus of a hydrogen atom is represented by a thumb-tack stuck in the middle of a football field, then the electron would be lurking somewhere in the furthest, uppermost row of seats in the surrounding stadium. In Rutherford’s model, the electric field intensity of the gold atomic nucleus is 100 000 000 times that of the Thomson model.

Isotopes

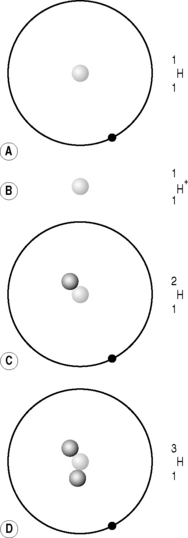

It quickly became apparent that a proton and a hydrogen ion were identical and that the majority of the atom’s mass (99.9995%) resided in the nucleus. There were, however, two problems with Rutherford’s proposed nuclear model. The first was that it didn’t account for isotopes. Isotopes are differing forms of an element; they have the same chemical properties but the mass of their atomic nuclei varies. For example, hydrogen has three isotopes, the common variety that we have just discussed with an atomic mass of approximately one proton; deuterium, which accounts for approximately 0.015% of all hydrogen and has an atomic mass equivalent to two protons; and the much rarer (1:10−15) tritium, which has a third ‘proton-mass’ (Fig. 6.4). The isotopes all have the same chemical properties – you can make H2O using deuterium or tritium; this is so-called ‘heavy water’– but different atomic mass numbers (A), 1 for hydrogen, 2 for deuterium and 3 for tritium.

Perhaps the isotope that has the greatest public awareness is carbon-14. Carbon, which has six protons (Z = 6), normally has an atomic mass number of 12; however, it also exists in a form where A = 14. Conveniently, this form is radioactive and decays slowly back into carbon-12. By finding the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-14, scientists are able to calculate the approximate age of organic materials, all of which contain large numbers of carbon atoms.

It is also the carbon atom that forms the basis for the definition of the mole, which, as we learned in Chapter 1, is one of the seven fundamental SI units (Table 1.1). You may recall that the mole was defined as the amount of a given substance that contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 0.012 kilogram of carbon-12.

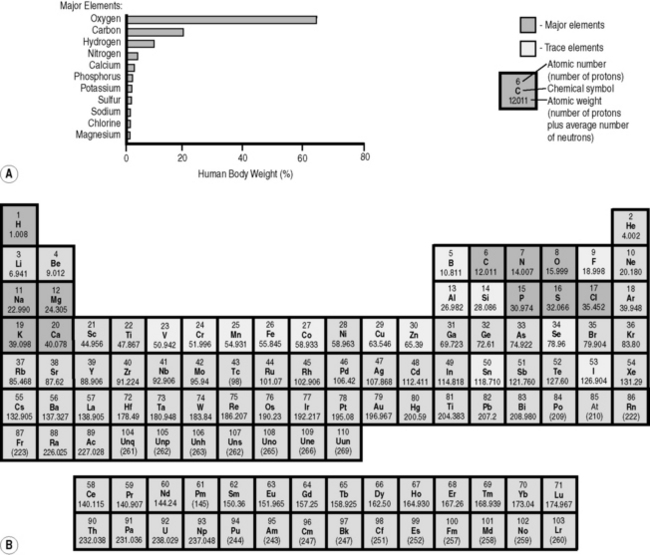

In the 1870s, Dmitri Mendeleev, a Russian chemist, found that, if he arranged chemical elements in order of increasing atomic weight, certain elements with similar properties – for example fluorine, chlorine, iodine and bromine – occurred periodically at regular and predictable intervals. He also spotted that there were obvious gaps in the table and was able to make predictions as to the chemical properties of the missing elements. As his predictions came to be realized, the Periodic Table (Fig. 6.1) became a standard reference tool for all scientists.

The three isotopes of carbon we discussed become  (six protons and six neutrons),

(six protons and six neutrons),  (six protons and seven neutrons) and

(six protons and seven neutrons) and  (six protons and eight neutrons). Examples of some of the elements that we have discussed, and others that you are likely to commonly encounter, are given in Table 6.1.

(six protons and eight neutrons). Examples of some of the elements that we have discussed, and others that you are likely to commonly encounter, are given in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Some common elements, their isomer nomenclature and comments

| Element (Z) | Nomenclature of common (>1%), natural isotopes | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (1) |  , (protinium), (deuterium)*, , (protinium), (deuterium)*,  (tritium)* (tritium)* | Ubiquitous in animal tissue, the element that facilitates magnetic resonance imaging |

| Helium (2) |  | Nucleus is an α-particle  |

| Carbon (6) |  * * | Carbon dating (see above). The backbone of organic molecules |

| Nitrogen (7) |  | Main component of air. Component of all proteins and DNA |

| Oxygen (8) |  | Essential for cellular respiration |

| Sodium (11) |  | Na+ ion is essential in cell membrane transport |

| Magnesium (12) |  | Catalyst for enzyme reactions in carbohydrate metabolism |

| Aluminium (13) |  | Used for X-ray filters and step-wedges |

| Chlorine (17) |  | Cl− ion is essential in cell membrane transport |

| Potassium (19) |  | Man-made isotopes used in medicine |

| Calcium (20) |  | Major component of bones and teeth; Ca2+ triggers muscle contraction |

| Iron (26) |  | Critical component of haemoglobin |

| Cobalt (27) |  | Man-made isotopes used in medicine |

| Copper (29) |  | Key enzymatic component. Used for X-ray filters and anodes/targets |

| Zinc (30) |  | Key enzymatic component |

| Tin (50) |  | Used for X-ray filters |

| Iodine (53) |  | Component of thyroid hormone. Radioactive, synthesized  used investigatively and therapeutically used investigatively and therapeutically |

| Barium (56) |  | Radio-opaque medium used in radiographic examination of the gastrointestinal tract |

| Gadolinium (64) |  | Commonest contrast agent for musculoskeletal MRI |

| Tungsten (74) |  | X-ray machine filament |

| Gold (79) |  | Used in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Was the original foil used by Geiger and Marsden |

| Mercury (80) |  | Used in traditional thermometers |

| Lead (82) |  | Used for X-ray and other radiation shielding |

| Radon (86) |  | Synthetic isotopes used in radiotherapy |

| Radium (88) |  | Synthetic isotopes used in radiotherapy |

* Not occurring at > 1% but listed because of inclusion in discussion above.

Fact File

Fact File

Fact File

Fact File Dictionary Definition

Dictionary Definition

Dictionary Definition

Dictionary Definition

Dictionary Definition

Dictionary Definition Dictionary Definition

Dictionary Definition