The labia minora are rich in blood vessels, elastic fibers, and sebaceous glands and have few, if any, sweat glands and little or no adipose tissue. Bartholin glands, which are homologous to Cowper glands in the male, are composed of lobules of mucus-secreting acini located bilaterally in the stroma of the vestibule, inferior to the hymen. They are palpable sometimes in thin women and are more easily detected when enlarged by inflammation or neoplasia (3). The major excretory duct of each Bartholin gland empties posterolaterally at the junction of the hymenal ring and labium minus. Each major duct, as well as each of the ductules, is lined by stratified transitional-type epithelium that changes to stratified squamous epithelium at its orifice. The lesser vestibular glands (Littre glands in males) are lined by a single layer of tall columnar mucinous cells. Robboy et al. (4) found from one to several hundred (usually 2 to 10) of these glands in 9 of 19 autopsied fetuses and young women whose vulvae were serially blocked for microscopic examination. Skene paraurethral glands, homologs to the prostatic glands, form a network that surrounds the urethra, primarily posteriorly and laterally (5). Most of the ducts open into the distal one-third of the urethral canal. Skene glands are lined by low columnar to tall cylindrical cells with occasional mucus-secreting cells. The paraurethral ducts are lined by columnar epithelium that changes to stratified squamous epithelium or transitional epithelium near their urethral openings. The local environment has very important effects on vulvar skin. The various factors producing this environment have been emphasized by Lawrence (6) and include the influence of sex steroids, age, and moisture.

The patterns of lymphatic drainage of the vulva are important to an understanding of the expected node dissections associated with surgery for vulvar neoplasia. The lymphatic channels of the anterior portion of the labia majora and minora and the prepuce of the clitoris drain into the superficial and deep femoral lymph nodes via the dense lymphatic network at the symphysis pubis (the presymphyseal plexus) or into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes (7). The superficial inguinal nodes form a horizontal chain between the skin and deep fascia, just inferior to the inguinal ligament. Lymph drainage ultimately proceeds to the external iliac system. Unilateral vulvar injection studies show lymph flow to contralateral pelvic nodes via anastomotic channels between both sides of the vulva or the pelvis (8). The obturator lymph node, located in the obturator fossa of the pelvis near the obturator nerve, is often large and is found inferior and lateral to the other external iliac nodes. A Cloquet (or Rosenmüller) lymph node is either the most superior lymph node of the deep femoral chain or the most inferior external iliac node that projects below the inguinal ligament. Way (9) noted that only about 8% of individuals have nodal tissue at this location. Iversen and Aas (8), however, using radioactive injections, found that the medial lacunar node of the external iliac chain (which perhaps is the Cloquet node) had nearly half of the total activity detected in removed pelvic nodes. In his vital dye studies, Eichner (10) noted that the Cloquet node was always involved initially and, if it was not stained, then dye was absent in the superficial and deep femoral nodes and in the iliac nodes. The lymphatic channels of the posterior vulva reach the femoral lymph nodes, bypassing the presymphyseal plexus.

Most of the lymphatic drainage of the clitoris is into the superficial femoral lymph nodes via the presymphyseal plexus. Plentl and Friedman (7) emphasized direct lymphatic communications from the clitoris to pelvic nodes. Way (9), however, has stated that there is no evidence for spread of cancer from the clitoris to the pelvic lymph nodes without initial involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes. Moreover, Iversen and Aas (8) failed to find a direct lymphatic pathway from the clitoris to the pelvic lymph nodes.

Lymph drainage from midline vulvar structures, such as the clitoris and perineum, is often bilateral. Most unilateral vulvar squamous cell carcinomas that metastasize do so to the ipsilateral groin lymph nodes. Approximately 5% of all carcinomas located on one side of the vulva metastasize to the contralateral lymph nodes only, and 15% of unilateral cancers metastasize bilaterally (9).

APPROACH TO SPECIMENS

Several types of vulvar biopsy and excision specimens may be submitted to the surgical pathology laboratory. For excisions of carcinoma, it is important to identify the primary tumor, search for multifocal lesions, document the depth (thickness) of tumor penetration, check the margins of resection, and examine all lymph nodes. A labeled digital picture is quite useful to indicate the sites selected for microscopic study. Alternatively, the specimen may be placed upside down on clear plastic and photocopied. Wide excision vulvar specimens contain underlying adipose tissue and fascia. A partial vulvectomy specimen retains as much normal vulva as possible. The tissue from the “skinning” vulvectomy consists of only epidermis and dermis. The total (simple) vulvectomy specimen contains the entire vulva, including subcutaneous tissue down to the deep fascia. The traditional radical vulvectomy with lymphadenectomy is an en bloc resection of the entire vulva, inguinal skin and subcutaneous tissue, femoral and inguinal lymph nodes, and portions of the saphenous vein. At present, most surgeons have abandoned the en bloc resection, using separate incisions for the inguinal node dissections. The radical hemivulvectomy is a unilateral radical vulvectomy with separate incisions for the groin dissections.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Although rare, there are a variety of congenital abnormalities of the vulva. They may be categorized as genital manifestations of specific genetic anomalies; developmental defects affecting the external genitalia only; and congenital abnormalities associated with anomalies of other anatomic regions, especially the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts. A newborn with ambiguous genitalia may be a virilized female, an imperfectly masculinized male, or a true hermaphrodite. The external genitalia of a true hermaphrodite also may have primarily male or female features. Female pseudohermaphroditism results from prenatal virilization and manifests as clitoral hypertrophy and, often, labial fusion. There may be a persistent urogenital sinus or penis with a penile urethra. Most frequently, female pseudohermaphroditism is caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Virilization results from excess adrenal androgens resulting from deficiencies in converting enzymes (11). Masculinization also develops from exposure to exogenous or maternal androgens. Although virilization is sometimes induced by exogenous testosterone or the synthetic androgen danazol (12,13), most instances have resulted from exposure to progestational compounds, which were used for the treatment of threatened abortion (14,15). Female pseudohermaphroditism has resulted from maternal androgen–producing neoplasms such as luteoma of pregnancy (16–18) and Krukenberg tumor with stromal luteinization (19–22). A purported maternal Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor causing congenital virilization more likely represents a luteoma (23). Congenital virilization also may be secondary to maternal adrenal adenoma (24–26), adrenal hyperplasia (27), or undetermined causes.

Malformations of the external genitalia are sometimes an isolated finding but often are associated with gastrointestinal or urinary tract defects (28–30). Complete absence or duplication of the external genitalia is virtually always associated with multiple anomalies, many of which are not compatible with life. Severe cases of labial fusion (chiefly resulting from exposure to androgens in utero) result in the covering of the vaginal and urethral orifices and the formation of a urogenital sinus. Labial adhesions (agglutination), which are more often an acquired condition, sometimes obstruct the urethral or vaginal orifices. Unilateral or bilateral hypertrophy of the labium minus is a common finding that, in actuality, may be a normal variant (31). An ectopic labium majus has been described (32). The clitoris may be absent, hypoplastic, hypertrophic, or bifid. Clitoral hypertrophy is most often associated with exposure to androgens in utero but is also found in rare conditions such as the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (11). A bifid clitoris may be a solitary abnormality or may be found with epispadias or exstrophy of the bladder (28). The hymen may be imperforate, microperforate, or rigid. An imperforate hymen often is not recognized until after puberty. A microperforate hymen usually is detected before menarche because it results in recurring vulvovaginitis and urinary tract infections (33). A persistent urogenital membrane sinus develops from fusion of the membrane with the inner labia minora, obliterating the introitus (34). The shallow sinus is covered by a thick membrane that contains a small aperture; the vagina and urethra open separately into the sinus.

Anomalies of the urinary tract that occur with malformations of the female external genitalia include epispadias, exstrophy of the bladder, and ectopic ureteral orifices. Ectopic ureters, which usually are accessory, open into the vagina or the vestibule. An ectopic ureterocele sometimes is seen as a cystic mass at the introitus (35). An ectopic anus opens more anteriorly in the perineum than normal or is found in the inferior portion of the vagina. In persistence of the cloaca, fused labial folds cover only a single narrow channel that empties onto the perineum via a small orifice; the bladder, genital tract, and bowel each open into this common cavity (28). In other cloacal malformations, the external appearance of the perineum is quite variable (30). A case of intestinal heterotopia resulting in a small vulvar ulcer in an adult has been described (36).

CYSTS

Epidermoid cysts are the most common vulvar cyst (37). They present as a round or oval, painless nodule primarily on the anterior half of the labia majora. Frequently, multiple cysts are present. Epidermoid cysts are found chiefly in adults, but one report described an epidermoid cyst of the labium majus in a newborn, who also had a bifid clitoris and skeletal anomalies (38). So-called traumatic inclusion cysts, also lined by squamous epithelium and filled with keratinous debris, are found at sites of previous surgery, especially episiotomy. Some have occurred in African women and children who have undergone ritual circumcision (39).

A vulvar pilonidal cyst (or sinus) typically involves the clitoral area (40). It consists of an abscess cavity filled with hair shafts that elicit a foreign body granulomatous reaction. A squamous lining may cover the superficial portion of the sinus tract, but most of the sinus tract is surrounded by granulation tissue.

A Skene duct cyst (paraurethral cyst) is usually less than 2 cm in diameter but may cause urethral obstruction (37). The cyst is lined by transitional epithelium, sometimes with squamous or ciliated cells (4,41–43). Although inflammation has been considered causal, most women lack a history of infection. When found in the newborn, a Skene duct cyst must be distinguished clinically from ectopic ureterocele, urethrocele, and urethral diverticulum (41). Spontaneous drainage of the cyst in the newborn occurs within a few weeks or months (43).

A hymenal cyst is the most common vulvar cyst of the female newborn (43). It is 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter and is lined by squamous epithelium. Spontaneous drainage of a milky fluid is characteristic.

The cyst of the canal of Nuck, similar to the hydrocele of the spermatic cord, results from incomplete obliteration of the processus vaginalis (44). This hydrocele is located along the course of the round ligament and is bordered by its occluded ends at the inguinal ring and labium majus. The nontender, elongated cyst varies in size, is occasionally multiple, and transilluminates. Unlike a hernia, it is typically irreducible. However, an inguinal hernia is present in one-third of cases (44,45). The cyst contains clear fluid and is lined by a single layer of cuboid or flattened mesothelial cells. The cyst must be excised because recurrence typically follows aspiration (45).

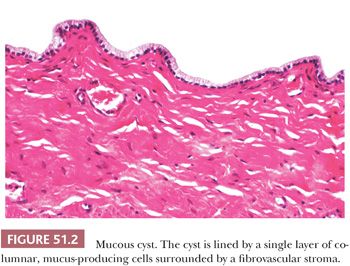

The mucous or mucinous cyst of the vestibule (4,46–48), virtually never seen before puberty, may be related to hormonal stimulation. Twenty percent of the cysts are multiple, and the mean size is approximately 1 cm (47). The cyst usually is unilocular and contains abundant mucoid material. It is lined by a single layer of tall columnar, mucus-secreting cells that have basal nuclei (Fig. 51.2). Papillary groups of cells, reserve cell hyperplasia, ciliated cells, and squamous metaplasia also may be present. The lining is surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma without smooth muscle cells. A müllerian origin was postulated formerly (46), but the mucous cyst is now considered to derive from urogenital sinus (minor vestibular gland) epithelium (4,47).

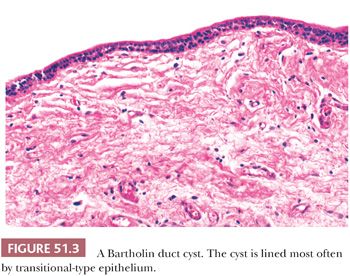

A Bartholin duct cyst results from occlusion of the major duct, with persistent secretion of the glands. The cyst occurs chiefly during the reproductive years and is usually unilocular, unilateral, and nontender (37). Large cysts may block the entrance to the vestibule. Unless infected, the cyst fluid is mucoid and clear. Transitional-type epithelium is the most common lining, but cuboid, columnar, ciliated, and squamous cells may be observed in varying proportions (Fig. 51.3) (3). The cyst wall contains a variable number of chronic inflammatory cells and normal or atrophic acini. A papilloma of a Bartholin gland duct cyst has been described (49). Mucocele-like changes of the Bartholin gland are observed after rupture of obstructed, dilated ducts with leakage of mucin (50). Vacuolated histiocytes are conspicuous in the stroma.

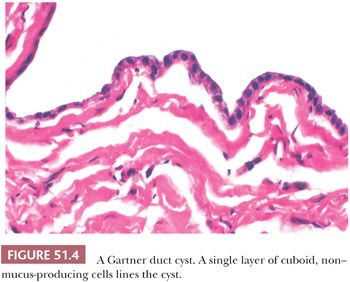

A Gartner duct cyst (mesonephric or wolffian cyst) occurs less often in the vulva than the vagina. A lining of nonmucinous, cuboid, or low columnar cells sometimes is accompanied by focal squamous metaplasia (Fig. 51.4). Smooth muscle fibers may be found in the cyst wall.

Fox-Fordyce disease is a chronic pruritic eruption of multiple, 1- to 3-mm papules or microcysts (51). The condition manifests in anatomic sites, which have apocrine glands. It has a predilection for the axilla and vulva, is very rare before puberty, and is uncommon after menopause. Microscopically, the superior portion of the hair follicle is obstructed by a keratin plug that also occludes the ostium of the apocrine duct. A vesicle then forms in the wall of the follicle after ductal rupture. Acanthosis and spongiosis of the follicle, dilatation of apocrine gland acini, and chronic inflammation of the dermis are also present. Multiple histologic sections often are necessary to identify the diagnostic microcysts (retention vesicles) (51).

Endometriosis manifests as blue or red, firm, cystic nodules that enlarge cyclically with menses. Endometriotic foci are found at sites of previous surgery, especially episiotomy (52).

Mammary-like vulvar glands may rarely give rise to involution cysts and hidrocystoma (53).

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Bacteria

The chancre of primary syphilis (Treponema pallidum) occurs as a painless, eroded papule or indurated ulcer with raised edges and a smooth, erythematous base. Microscopically, the central surface epithelium is attenuated or ulcerated. There is an intense infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the edematous ulcer bed and prominent proliferation of capillaries with swollen endothelial cells. In smears of the exudate, the characteristic spiral organism may be visualized using darkfield examination or immunofluorescence with antitreponemal antibodies (54). In paraffin sections, the organisms may be seen with the Warthin-Starry or Steiner stains, or with antisera using the immunoperoxidase technique (55). Secondary syphilis of the vulva, condyloma latum, manifests as moist, gray-white patches or flat-topped papules, which usually appear from 3 to 6 weeks after the chancre. They are highly contagious, containing many spirochetes. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is conspicuous, and neutrophils may migrate into the epithelium. The chronic inflammatory and endothelial cell changes are similar to those of the chancre. Tertiary syphilis is rarely observed in the vulva.

Vulvar infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae usually involves Skene or Bartholin glands and is often accompanied by gonococcal cervicitis, urethritis, or proctitis. The vulvar glands are swollen and painful, with abscess formation. Culture of the organism is essential for diagnosis. Although gonococci were believed responsible for most abscesses of the Bartholin gland, in one study they were cultured from only 17% of the abscesses that contained bacteria (56).

Granuloma inguinale (Calymmatobacterium granulomatis) is rare in the United States and is largely confined to the southern states (57). It manifests as solitary or multiple painless papules, which ulcerate and have serpiginous, rolled borders. Marked tissue destruction may ensue with extensive scarring and elephantiasis (54,57). Inguinal lymphadenopathy generally is mild. Microscopically, there is exuberant pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (58), granulation tissue, and an inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells, scattered polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and characteristic vacuolated histiocytes. The histiocytes contain 0.6- to 2-μm encapsulated rods with bipolar granules (Donovan bodies). These Gram-negative bacteria are difficult to identify in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained paraffin sections but are better visualized with Wright, Giemsa, toluidine blue, or Warthin-Starry stains. They are readily apparent in Papanicolaou-stained smears (59). The florid pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia must not be confused with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). There are, however, well-documented reports of vulvar SCC arising in areas of chronic granuloma inguinale infection (60,61).

Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi) is an unusual venereal disease in the United States. It begins as a small papule or pustule, usually on the vestibule. Later, painful, soft, single, or multiple ulcers develop that have ragged edges with erythematous borders. Enlarged inguinal lymph nodes with suppuration (buboes) are present in approximately one-fourth of cases (62). Endothelial proliferation is prominent beneath the surface ulceration and necrotic debris, and there may be lumenal compromise and thrombosis. Lymphocytes and plasma cells densely populate the deep dermis. Culture isolation of the Gram-negative organism is necessary for diagnosis (63).

The vulva is the least common site for tuberculosis of the female genital tract (64). Vulvar tuberculosis results from hematogenous dissemination or spread from the upper genital tract. It also may be transmitted sexually from a male partner harboring tuberculous epididymitis. Grossly, the infected vulva is ulcerated or hypertrophic and may mimic SCC. Culture is usually necessary for diagnosis, given the low sensitivity of acid-fast stains (65). Women with leprosy sometimes have vulvar involvement.

Erythrasma (Corynebacterium minutissimum) forms symmetric, erythematous inguinal macules that may simulate infection with tinea or Candida. The condition is asymptomatic and is almost never biopsied. The organisms are located in the horny layer of the epidermis. Diagnosis is confirmed by orange-red fluorescence with a Wood lamp (66).

Impetigo and ecthyma may spread to the vulvar area in children. Folliculitis and erysipelas of the vulva are typically caused by staphylococci and streptococci, respectively. These microorganisms, as well as a variety of other aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, also may be involved in deep abscesses, cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis (67). Necrotizing fasciitis is a toxic, systemic illness that follows surgery or minor trauma. The disease usually occurs in diabetics and is rapidly progressive and may be fatal (68). Grossly, the vulva is erythematous and swollen. The superficial fascia and subcutaneous tissue are necrotic, but the underlying muscular layer is spared. Microscopically, the subcutaneous tissue shows necrosis, acute inflammation, and thrombosis and necrosis of small vessels. Bacteria can be seen in the necrotic tissue. Aggressive surgical resection is the most important therapeutic modality.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic inflammatory process involving sites replete with apocrine glands. The disease is virtually never seen prior to puberty and has a peak incidence in the third decade of life (69). Follicular and intraepidermal apocrine duct occlusion by keratin with perifolliculitis and apocrine adenitis leads to the formation of abscesses. Chronic inflammatory cells, foreign body giant cells, granulation tissue, fibrosis, and deep sinus tracts follow destruction of cutaneous appendages. Cultures usually reveal a spectrum of bacterial pathogens (69). Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for severe cases (70).

Bacillary angiomatosis of the vulva has been reported in a patient with AIDS and is characterized by a mixed endothelial and histiocytic proliferation with neutrophils. Warthin-Starry stains will reveal abundant masses of small, weakly Gram-negative Bartonella henselae (71).

Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes L1 to L3 cause lymphogranuloma venereum, and serotypes D to K are associated with sexually transmitted oculogenital disease (72). The initial manifestation of lymphogranuloma venereum is a small, asymptomatic vesicle, papule, or ulcer, frequently on the posterior vulva (54). Swollen inguinal lymph nodes with suppuration occur after a few weeks. The histopathologic features of the ulcer include marked chronic inflammation, a few giant cells, necrosis, granulation tissue, fibrosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The lymph nodes show follicular hyperplasia and characteristic, but nonspecific, stellate microabscesses, raising the differential diagnosis of cat scratch disease. In long-standing infection, there is extensive scarring, with strictures and fistulas of the vulva, urethra, vagina, and rectum. Chronic lymphedema and obstruction may result in elephantiasis. SCC of the vulva has been reported in women with previous infection (61). The most important technique for the identification of oculogenital chlamydia has been culture isolation. The characteristic intravacuolar organisms in vacuolated macrophages have been observed in suppurative inguinal lymphadenitis of lymphogranuloma venereum (73). They are Gram-negative, stain faintly blue with H&E, and are black with the Warthin-Starry silver impregnation stain. Electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers for chlamydial 16S ribosomal DNA can be used to detect the organisms in tissues. C. trachomatis also has been isolated from duct exudate of the Bartholin gland (74).

Viruses

Herpes simplex is the most common cause of vulvar ulcers. Genital tract infection results more often from type 2 rather than type 1 virus (75). An intraepithelial herpetic vesicle forms from acantholysis of the squamous epithelium because of ballooning and reticular degeneration. Subsequent rupture forms a painful superficial ulcer. The inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis varies; polymorphonuclear leukocytes and vasculitis may be present. At the periphery of the ulcers, mononucleate or multinucleated epithelial cells contain “ground-glass” nuclei or eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions. The inclusions are seen in both H&E-stained histologic sections and in Papanicolaou- or Giemsa-stained cytologic preparations.

Rarely, herpes zoster (76,77), vaccinia (78), Epstein-Barr virus (79,80), and cytomegalovirus (81) have resulted in vulvar infection. HIV has been cultured from genital ulcers in HIV-positive women, but most genital ulcers in HIV-positive women do not contain HIV (81).

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are among the most common vulvar infections and cause squamous proliferations of the skin and mucous membranes. New genotypes continue to be reported and are defined as such when the DNA sequence has more than a 10% difference in defined regions from other established HPV genomes. More than 30 mucosotropic types involve the anogenital tract and, because of the keratinized portions, there may be some cutaneous types present as well. Infections with multiple genotypes are not unusual, although usually they are in independent lesions. Papillomavirus infection occurs anywhere on the external genitalia and is most commonly observed in women of childbearing age. Vulvar warts (condylomata acuminata) appear as pink or gray-white, soft, sessile, or verrucous growths that may become confluent (Fig. 51.5). Vulvar vestibular squamous papillomatosis—small, sometimes pruritic growths on the vestibule—have been considered to result from papillomavirus only in a minority of women (82,83). More often, multiple papillae that lack evidence for papillomavirus, so-called micropapillomatosis, represent abnormal anatomic variants of the vulvar vestibule (84,85). These uniform and symmetric micropapillations lack the classic cytologic features of condylomata (86,87).

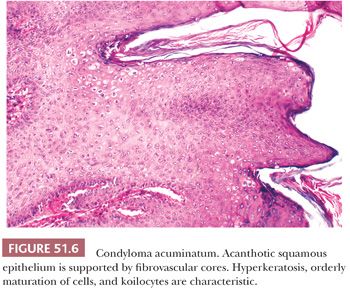

Recurrence of genital warts is caused by reinfection or latent viral activation (88). Microscopically, condyloma acuminatum is characterized by delicate, branching fibrovascular cores (papillomatosis) lined by squamous epithelium showing acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis (Fig. 51.6). The parabasal layer is thickened, and there is minimal nuclear enlargement and pleomorphism of parabasal cells. Relatively, orderly maturation and normal cellular polarity are retained. Mitotic figures may be identifiable, but atypical mitoses are absent. Koilocytosis is the characteristic cytopathic effect of papillomavirus infection. Koilocytes are superficial or intermediate squamous cells with single or occasionally multiple, enlarged, hyperchromatic, and wrinkled nuclei. Surrounding the nucleus is a prominent clear space or “halo,” which abuts a thickened zone of peripheral cytoplasm. Binucleate forms typically are present. Electron microscopic, IHC, and in situ hybridization studies have shown that the viral particles are concentrated in the nuclei of koilocytes and parakeratotic cells (89).

Lesions caused by HPVs should not be confused with multinucleated atypia of the vulva in which multinucleated cells are confined to the lower or middle epithelial layers (90). Unlike condyloma and intraepithelial neoplasia, surface atypia is absent and nuclear hyperchromasia, irregularity, and variation are not seen in the multinucleated cells. This focal histologic change usually occurs in young women, but it is unclear that it results in a clinically visible vulvar lesion.

Podophyllin therapy for condyloma acuminatum may produce cytologic changes mimicking intraepithelial neoplasia. Microscopically, the effects are most pronounced within 48 hours after treatment and are absent after 1 week (91). Typically, there are intercellular edema; necrosis of the basal half of the epidermis; and an edematous, inflamed papillary dermis. Mitotic figures (with a few bizarre forms) are markedly increased. Unlike intraepithelial neoplasia, orderly squamous cell maturation is present; marked nuclear atypia and dyskeratotic cells are absent.

Occasionally, papillary vulvar lesions have some features suggestive of condyloma acuminatum but lack koilocytotic atypia. In such cases, molecular studies can be used to assess the possibility of a viral etiology; 20% to 70% of these condyloma-like lesions have detectable papillomavirus DNA (92,93). These lesions may represent regressing condylomata.

Differential Diagnosis. Vulvar condyloma acuminatum or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) is usually easy to distinguish from vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). For the latter, pleomorphic, enlarged, and hyperchromatic parabasal nuclei; disorderly maturation; and abnormal mitotic figures are conspicuous (94). The nuclei of condyloma acuminatum/LSIL are diploid or polyploid, whereas those of HSIL typically are aneuploid (89,95). Focal koilocytotic atypia and cellular maturation may be observed in or adjacent to intraepithelial neoplasia. Although most vulvar LSIL occurs in the form of condylomas, some examples of LSIL represent flat condyloma acuminatum, a pattern that is common on the cervix but rare on the vulva. There is abundant evidence at clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, IHC, and molecular levels that HPV infection is linked to premalignant and malignant squamous proliferations of the vulva (89,96–108). HPV DNA has been noted in 80% to 100% of genital intraepithelial neoplasia and bowenoid papulosis (98,104–107). Viral DNA also has been demonstrated in a subset of verrucous carcinoma (100,101) and some types of SCC of the vulva (98,102,108,109). Viral types 6 and 11 frequently are observed in vulvar condylomata acuminata (88,98,100,103,106), whereas types 16, 18, and 31 and other high-risk types have been found more often in HSIL and cancer (98,102,106–109). The relationship between condylomata and HSIL is discussed further in “Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion and Relevant Related Conditions” later in this chapter.

Molluscum contagiosum is a DNA poxvirus that has a predilection for the vulva of postpubertal women. This mildly contagious infection appears as multiple, 1- to 4-mm papules with central umbilication. The papules often disappear spontaneously after approximately 6 months, but others may remain for several years (110). Microscopically, the follicular epithelium expands to produce rounded lobules of cells and keratinized debris (111). Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies enlarge and become basophilic as they migrate from the deeper layers of the epidermis. The diagnostic viral inclusions also may be observed in cytologic material obtained by squeezing the papules.

Fungi and Parasites

Tinea cruris causes erythematous, scaly patches in the perineal, inguinal, and vulvar areas. The diagnosis is determined by culture or identification of hyphae in potassium hydroxide–treated skin scrapings.

Vulvar cutaneous candidiasis commonly accompanies vaginal infection. The erythematous, pruritic lesions may involve large areas of the vulva and perineum. Small pustules are sometimes also present. Severe infection is associated with obesity and diabetes mellitus. Microscopically, the epidermis is mildly thickened and spongiotic; a chronic inflammatory infiltrate is present in the dermis. The surface contains degenerated squamous cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, yeast, and pseudohyphae.

Deep fungal infections of the vulva are very rare. Clinically, they may simulate necrotizing fasciitis. Phycomycosis of the vulva has been reported in diabetic women (112).

Although superficial genital parasites are common (lice and scabies), invasive parasitic infestation of the vulva is rare in North America. Vulvar elephantiasis sometimes results from lymphatic obstruction by filariform worms. Schistosomiasis may cause ulcers or papillary nodules that simulate condylomata acuminata (113).

MISCELLANEOUS BENIGN LESIONS

Seborrheic keratoses and fibroepithelial polyps occur on the labia majora of middle-aged or elderly women. The latter may contain scattered pleomorphic stromal cells and may appear identical to the vaginal stromal polyp (114). Identical pleomorphic stromal cells have been found in nearly 80% of adults whose vulvae were biopsied or resected for intraepithelial neoplasia or squamous carcinoma (115). Two cases of verruciform xanthoma of the vulva have been described (116). This warty lesion is characterized by acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with deep extension of the rete pegs and an associated neutrophilic infiltrate. There is also hyalinization of dermal collagen, a few lymphocytes and plasma cells, and conspicuous xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis between the rete pegs. Sebaceous gland hyperplasia forms smooth, soft dermal nodules up to 1.5 cm in diameter on the labia minora or majora (117). Nodular hyperplasia of Bartholin gland presents as a solid or solid and cystic mass, usually less than 5 cm and is composed of a nodular proliferation of mucinous acini with maintenance of the normal ductal–acinar architecture (118). Minor vestibular gland adenoma occurs as a firm nodule less than 2 cm in size (119). The nodules of mucus-secreting glands have been associated with previous surgery or chronic inflammation. Some authors believe the lesion has more features of nodular hyperplasia of minor vestibular glands than an adenoma (120). Pilar tumor, usually found on the scalp, has been reported to occur on the vulva (121). In epidermolytic acanthoma, multiple small nodules show acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and a prominent granular layer (122). Keratoacanthoma only rarely has been described as occurring in the vulva (123).

Benign vulvar melanocytic lesions include lentigo (124,125) and nevi (congenital or acquired). The former uncommonly are multiple and large and have irregular borders. Multiple genital lentigines have been associated with cardiac abnormalities (124). Rare junctional or compound vulvar nevi in premenopausal women may be atypical and have some architectural features of melanoma, including wide lateral extent, confluence and variation in size and shape of junctional nests, and involvement of adnexal structures (126,127). Unlike melanoma, atypical vulvar nevi have a well-demarcated epidermal melanocytic component, lack melanocytes at all levels of the epidermis, and show maturation of melanocytes from the epidermis to the dermis (126). In vulvar hyperpigmentation (melanosis), there is dermal deposition of melanin but no melanocytic hyperplasia.

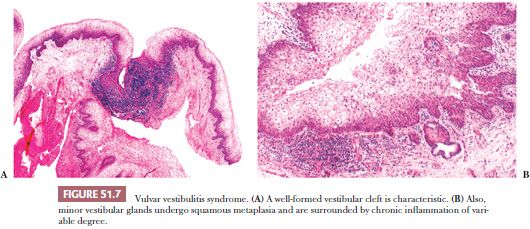

Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, an idiopathic chronic condition in which there is tenderness after touching the vestibule and dyspareunia in young women, also has been termed focal vulvitis, hyperesthesia of the vulva, and infection of the minor vestibular gland (128). Grossly, there is focal erythema at the openings of the minor vestibular glands. Microscopically, there is a mild to severe chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria and superficial stroma around the glands (Fig. 51.7). Usually, the intensity of the infiltrate is mild or moderate. There is a predominance of T lymphocytes and plasma cells with fewer B cells (120). The surface squamous epithelium often is infiltrated by lymphocytes and shows spongiosis, parakeratosis, or hyperkeratosis. Ductal epithelium may be infiltrated by lymphocytes but the glandular acini typically are not affected. Squamous metaplasia involves the duct or acinus or both. At low power, a vestibular cleft at the opening of the duct is created by extensive squamous metaplasia that may entirely replace the minor vestibular gland. HPV DNA has been found in only rare cases and is most likely not an etiologic factor (120,129). Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome is most successfully treated with resection combined with psychological intervention (120).

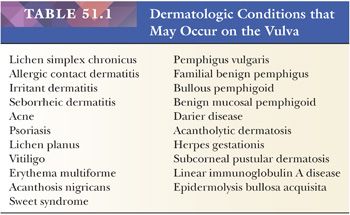

A variety of dermatologic conditions may involve the vulva, either as a localized process or as part of generalized disease (Table 51.1) (refer to Fox-Fordyce disease in “Cysts” earlier in this chapter). Specific dermatoses affecting the vulva are sometimes not identified by either the gynecologist or the surgical pathologist (130). The special anatomic features of the vulva and its local environment may modify the clinical appearance of a specific dermatosis and render the clinical diagnosis more difficult.

Radiation damage to the vulva, although uncommon, results in loss of pubic hair and sclerosis of the connective tissue and blood vessels. Because Reiter syndrome is exceedingly rare in the vulva, the histopathologic features are not well characterized (131). Behçet syndrome, a chronic, relapsing disease, manifests as small vesicles or pustules that may develop into deep ulcers. Microscopically, there is a necrotizing vasculitis with swollen endothelial cells, fibrinoid necrosis of vascular walls, and a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate (132). Persistent red-brown or orange glistening papules or macules and erosions are characteristic of vulvitis circumscripta plasmacellularis or Zoon vulvitis (133–135). The microscopic features of this idiopathic condition include an inflamed epidermis, parakeratosis, telangiectasia, and a dense dermal infiltrate of plasma cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

Lipoma and fibrolipoma occur on the labium majus as solitary subcutaneous nodules and pedunculated masses (136). Sclerosing lipogranuloma, because of trauma or injection of foreign oils, is characterized by vacuolated cysts lined by adipocytes or giant cells with adjacent bands of hyalinized tissue. The lesion may be locally infiltrative and should be distinguished from liposarcoma (137). Vulvar leiomyomas are three times more common than leiomyosarcomas (138). Criteria have been developed to predict the behavior of vulvar smooth muscle tumors (138,139). Neoplasms that have at least three of the following features are considered sarcomas: 5 cm or more in diameter, infiltrating margins, five or more mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields (hpfs), and moderate to severe cytologic atypia. Tumors with only one of these features should be considered leiomyomas, whereas those with two of the characteristics should be considered atypical leiomyomas. Rare leiomyomas have evolved into leiomyosarcomas (138). Epithelioid leiomyoma (139,140) appears to have a greater proclivity to recur than the usual spindle cell type. Leiomyomas excised during pregnancy may have extensive myxoid change, hemorrhage, or foci of necrosis (139). An unusual syndrome of diffuse vulvar and gastroesophageal leiomyomatosis has been described in at least 20 patients, most of whom also have Alport syndrome (141,142). Vulvar neurofibroma can occur as an isolated lesion or as part of neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) (143,144). Rarely, there is extensive involvement of the genitourinary tract (145). Other neural tumors, including schwannoma (146,147), plexiform schwannoma (148), traumatic neuroma, and paraganglioma (149), may arise in the vulva. Granular cell tumor occurs as a single (or multiple) superficial nodule on the labium majus or clitoris and strongly predilects black women (see “Malignant Neoplasms” later in this chapter) (150,151). The overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may mimic well-differentiated SCC (150). Solitary fibrous tumor (152), nodular fasciitis (153), postoperative spindle cell nodule (154), desmoid tumor (155), and genital rhabdomyoma (156) only rarely involve the vulva.

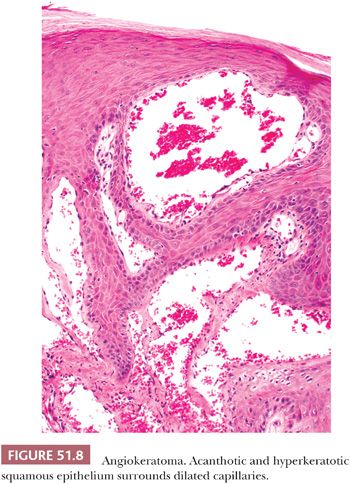

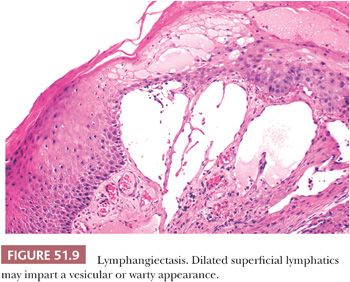

Benign vascular lesions of the vulva include capillary (strawberry) hemangioma, senile hemangioma, cavernous hemangioma, congenital dysplastic angiopathy, angiokeratoma, lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) (136), and varicosities. Lobular capillary hemangioma and varicosities are seen most often during pregnancy. Cavernous hemangioma may involve the clitoris, simulating pseudohermaphroditism (157). Angiokeratomas often are multiple, 2- to 10-mm in diameter, papillary, warty, or globular lesions of the labia majora (158). They are associated with pregnancy and increased venous pressure. Microscopically, dilated, often thrombosed, capillaries are found in the upper dermis, surrounded by acanthosis and hyperkeratosis of the overlying squamous epithelium (Fig. 51.8). Glomus tumor, arising on the labium minus or clitoris, causes persistent pain and dyspareunia (159,160). Lymphangiomas are rarely observed on the vulva (161). Lymphangiectasis (acquired lymphangioma) arises as multiple vesicles or warty papules on the labia majora and develops in chronic lymphedematous states after radiation therapy or surgery (162,163). Microscopically, thin-walled, ectatic lymphatic channels are located superiorly in the papillary dermis (Fig. 51.9).

The concept of “milk lines” and vulvar lesions derived from these rudiments recently has been challenged (2). It has been proposed that a variety of lesions that commonly occur in the breast as well as hidradenoma papilliferum and extramammary Paget disease arise from mammary-like glands. These anogenital “sweat” glands resembling mammary ducts are found incidentally, chiefly in the interlabial sulcus (Fig. 51.1) (1). It is possible that most examples of accessory breast tissue develop from these anogenital sweat glands and not from caudal remnants of the milk line (1). Clinically apparent mammary-like tissue is sometimes found in the labial area and may be bilateral (164). Very rarely, a nipple is present. Because of hormone-induced swelling, vulvar mammary-like tissue becomes manifest during pregnancy or lactation. Fibrocystic changes, lactating adenoma (165), fibroadenoma (166), intraductal papilloma (167), and phyllodes tumor (168) all have developed in mammary-like breast tissue. Adenocarcinoma also may arise in vulval mammary-like tissue (169–171) and must be distinguished from conventional cutaneous adenocarcinomas of apocrine or eccrine origin and metastatic mammary carcinoma.

Crohn disease involves the vulva by direct extension from the anus or as a discontinuous, “metastatic” ulcer. The latter shows granulomatous inflammation, acute and chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and sometimes extensive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (172). Most, but not all, patients with Crohn vulvitis have had a history of intestinal Crohn disease (173). A chronic granulomatous hypertrophy of the labia, vulvitis granulomatosa, resembles Crohn disease because there is edema, fibrosis, lymphangiectasia, chronic inflammatory cells, and nonnecrotizing granulomas (173). There appears to be a relationship among vulvitis granulomatosa, cheilitis granulomatosa, and Crohn disease. Sarcoidosis (174), malacoplakia (175,176), amyloidosis (localized or systemic) (177), calcinosis (178,179), mucinous metaplasia (180), lymphoid hamartoma (181), and ectopic salivary gland (182) of the vulva also have been described. A case of rheumatoid nodule with ulceration and lymphadenopathy has been reported that clinically mimicked carcinoma (183). A lymphoma-like lesion has been reported in a patient with infectious mononucleosis (80).

AGGRESSIVE ANGIOMYXOMA, ANGIOMYOFIBROBLASTOMA, AND CELLULAR ANGIOFIBROMA

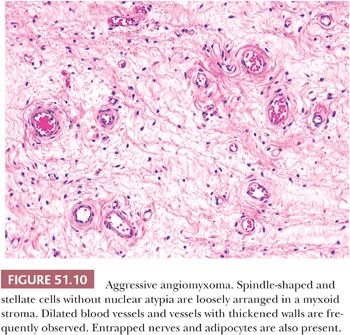

Deep aggressive angiomyxoma occurs in the vulva, vagina, perineum, inguinal area, or pelvic soft tissues (184–187). It presents as a large, slow-growing, polypoid mass or swelling in women who are most often in their third or fourth decade of life. Grossly, the tumor is rubbery and white or soft and gelatinous. Most are at least 10 cm in greatest dimension (186). Microscopically, stellate and spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells are embedded in a loose myxoid stroma with a few collagen fibers (Fig. 51.10). The cells are small and bland, and lack nuclear atypia. Small or medium-sized veins and arteries within the tumor often are grouped together and may show medial hypertrophy. Blood vessels of various caliber are typically widely dilated, and extravasation of red blood cells is usual. Aggressive angiomyxoma is characteristically hypocellular and lacks necrosis and mitotic figures. Invasion of skeletal muscle and fat is usual. Small nerves often are trapped within the neoplasm. The tumor cells have fibroblastic or myofibroblastic properties ultrastructurally. By IHC, they are at least focally positive for desmin, smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and vimentin (186). CD34, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor also are commonly present.

Differential Diagnosis

The microscopic differential diagnosis includes angiomyofibroblastoma, cellular angiofibroma, neurofibroma, intramuscular myxoma, myxoid smooth muscle tumors, spindle cell lipoma, myxofibrosarcoma, myxoid liposarcoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and massive vulval edema. A few tumors have shown histologic features resembling those of angiomyofibroblastoma (187). The therapy for aggressive angiomyxoma is complete excision. Local recurrence, often many years following initial resection, is common (36% to 72%); metastases are extraordinarily rare (188). In one series of 29 patients, there were no tumor-related deaths (186).

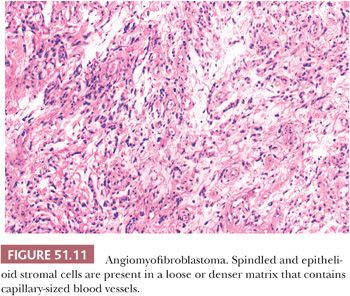

Angiomyofibroblastoma may be confused with deep aggressive angiomyxoma. The vulva and, to a lesser extent, the vagina are sites of predilection for this histologically distinctive, benign soft tissue lesion (152,189–191). This tumor presents as a polypoid submucosal mass ranging from 0.5 to 12 cm in size. Affected women are in their third to ninth decades of life. Grossly, the tumors are sharply demarcated; tan, pink, or yellow in color; with a spongy soft-to-firm consistency. This appearance is not dissimilar to that of aggressive angiomyxoma. Microscopically, angiomyofibroblastomas retain their sharp circumscription and are characterized by alternating areas of hypercellularity and stromal edema with hypocellularity. There are abundant but irregularly distributed capillary-sized blood vessels or small veins, often surrounded by loose aggregates of spindled stromal cells (Fig. 51.11). Some stromal cells may be larger and more epithelioid or plasmacytoid in appearance. Binucleated and multinucleated stromal cells, often with linearly arranged nuclei, also may be present (190). Entrapped mucosal glands or nerves are rarely present within the mass (152,189). Intralesional fat may be focal and entrapped or, less often, massive and an intrinsic component of the tumor (152). Nuclear pleomorphism typically is mild, although rare hyperchromatic, probably degenerative cells have been described. Mitotic activity is sparse with fewer than one mitotic figure per 10 hpfs (189,190).

Differential Diagnosis. Light microscopic features of angiomyofibroblastoma that distinguish it from aggressive angiomyxoma include marginal circumscription, higher cellularity, larger numbers of blood vessels lacking hyalinization or hypertrophy, often plump stromal cells with perivascular accentuation, a paucity of stromal mucin, and only rare extravasated erythrocytes (188). IHC studies have not been of value in making this distinction because both lesions display myofibroblastic features with vimentin, desmin, and actin reactivity (189–191). Both tumors also have been shown to have stromal cells which are reactive for estrogen receptor protein (152,191). The distinction of these two lesions is important because of their different clinical behaviors. Unlike aggressive angiomyxomas, angiomyofibroblastomas do not recur following local excision. One case of angiomyofibroblastoma with sarcomatous transformation has been described (192).

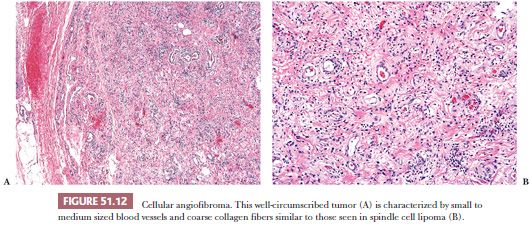

Cellular angiofibroma is a benign spindle cell tumor of the vulva that is distinct from both aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma (193). This tumor occurs in middle-aged women and measures 1.2 to 2.5 cm in size. Microscopically, the tumor consists of a monotonous spindle cell proliferation, often admixed with small foci of mature fat and coarse collagen fibers, not unlike those seen in spindle cell lipoma (Fig. 51.12). Focally prominent myxoid matrix may be present. Small to medium-sized blood vessels with prominent mural hyalinization are common. Entrapped small nerves may be encountered at the periphery of the lesion. The lesions are nonreactive for CD34, a marker often positive in spindle cell lipomas.

Other mesenchymal lesions that can occur in the vulva include ischemic fasciitis, perineal nodular induration (biker’s nodule), prepubertal fibroma, bilateral vulvar enlargement due to massive localized lymphedema, superficial myofibroblastoma, and superficial angiomyxoma. Perineal nodular induration consists of a poorly circumscribed bland spindle cell proliferation involving fibroadipose and fibrous tissue; areas of fat necrosis, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, multinucleated histiocytes, and extracellular hyalinization with degenerative features may be present. The spindle cells express vimentin but not actin, desmin, or CD34. The lesion, which is seen more frequently in men, develops as a result of repetitive perineal trauma; a history of cycling or horseback riding is common (194). Prepubertal fibroma (asymmetric labium majus enlargement of childhood) presents as a painless, unilateral vulvar mass in prepubertal girls (195,196). Typically arising in the region of the labium majus, it consists of a poorly circumscribed proliferation of bland, mitotically inactive spindle cells set in a hyalinized, myxoid, or edematous matrix. The lesional cells, which are positive for CD34 but not for desmin, smooth muscle actin, or S-100 protein, extend to the surface epithelium and entrap blood vessels, fat, and nerves. Recurrences may occur if incompletely excised. Massive localized lymphedema presents as papillomatous plaques, polyps, generalized vulvar enlargement, or massive pedunculated masses in obese or immobilized women (197). The chief microscopic finding is stromal edema, but multinucleated giant cells, dermal fibrosis, dermal lymphangiectasia, dermal chronic inflammation, perivascular chronic inflammation (superficial and/or deep), hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and blood vessels of varying calibers may also be seen. Superficial myofibroblastoma is a well-circumscribed lesion composed of bland ovoid to spindle-shaped cells arranged in a variety of architectural patterns and set in a finely collagenized or myxoid stroma (198,199). This lesion, which is more common in the cervix and vagina, typically measures less than 5 cm. The constituent cells, which often contain wavy nuclei reminiscent of a neural tumor, express desmin and CD34 but not S-100 protein. Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, small cutaneous lesion that exhibits a multilobulated growth pattern and has a significant potential for local but nondestructive recurrence (up to 40%) (200). These lesions are centered in the dermis and superficial subcutaneous tissue and feature abundant myxoid stroma with bland fibroblasts; scattered inflammatory cells; and thin-walled, capillary-sized vessels. Up to one-third contain an epithelial or adnexal component, secondary to entrapment. Necrosis is absent. Superficial angiomyxomas may arise in a wide variety of anatomic regions; when multiple or presenting at a young age, an association with Carney complex should be considered.

VULVAR SQUAMOUS INTRAEPITHELIAL LESION AND RELEVANT RELATED CONDITIONS

Historically, many confusing and overlapping clinical terms have been used to describe lesions found alone or adjacent to squamous carcinomas of the vulva. In the 1970s, most of these terms were replaced by the term vulvar dystrophy associated with or without cytologic atypia and squamous carcinoma in situ. In the 1980s, with an increasing appreciation for etiology, the International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease (ISSVD) revised the terminology with dystrophy referring to reactive conditions and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) referring to dysplastic or preneoplastic conditions. However, as our knowledge has progressed, this dichotomy has proven problematic because our concepts of two parallel pathways of squamous carcinogenesis have evolved. In 2004, the ISSVD once again revised the terminology establishing VIN as the precursor of vulvar carcinoma but limiting VIN to what was previously called high-grade VIN or VIN 2/3. This revision also essentially banned the use of the term VIN 1 or low-grade VIN (201). This was problematic as there are data that clearly show that a lesion that can be defined as VIN 1 exists and has an HPV-type profile distinct from condylomata and more analogous to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 (CIN 1) (107).

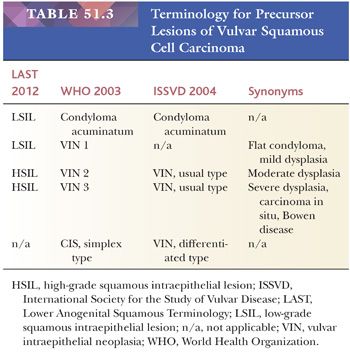

To address the discrepancies between various nomenclatures, a standardized terminology for vulvar dystrophy and squamous intraepithelial neoplasia has been developed to accommodate all lower anogenital HPV-related preneoplastic squamous lesions. (Table 51.2) (202). In brief, the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) Project recommends a two-tiered nomenclature system—LSIL and HSIL—which can be further qualified by the grade of intraepithelial neoplasia. The squamous intraepithelial lesion terminology parallels the Bethesda system, which has been in use since 1988 and was developed for providing uniform diagnostic terminology for cervical cytologic specimens. The LSIL category encompasses condyloma and CIN grade 1, whereas the HSIL category encompasses CIN 2 and CIN 3 (Table 51.3). CIN 1 is equivalent to mild dysplasia, CIN 2 to moderate dysplasia, and CIN 3 to severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. The term vulvar dystrophy, although outmoded, can be retained as a clinical term for continuity and to allow for better communication with clinical colleagues not yet fully conversant with the new terminology, but it should not be used to refer to a specific HPV-related dysplastic lesion.

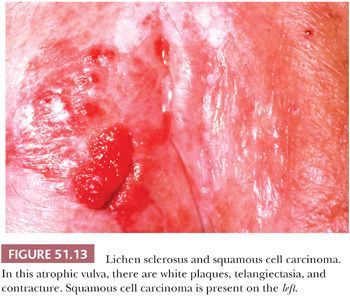

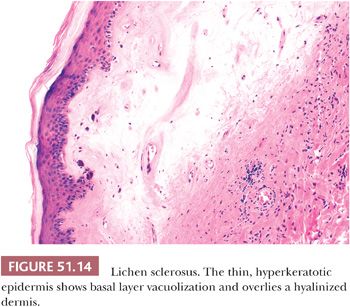

Because of the variable and overlapping clinical appearances of dystrophic and dysplastic conditions, biopsy of one or more lesions in a particular patient is often essential. In addition, it is important to screen the entire lower anogenital tract as vulvar HSIL is often multicentric, and extension to the perineum and involvement of the cervix and vagina is not uncommon. Lichen sclerosus, a persistent and recurring condition found at all ages, is seen predominantly in postmenopausal women, although children are also affected. All or any part of the vulva may be involved, with occasional extension to the perianal region and inner thighs. Lesions often are multiple, bilateral, and symmetric. Initial pale pink or white maculopapules coalesce to form dry, rough, scaly plaques (Fig. 51.13). Advanced lesions appear wrinkled and parchment-like, with telangiectasia and ecchymoses frequently observed (203). Extensive vulvar contracture may lead to agglutination of the labia minora and stenosis of the introitus. Microscopically, there is epithelial thinning, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and plugging of follicles (Fig. 51.14). However, the epithelial thickness can be variable and may even be normal or show reactive hyperplasia. The basal cells are vacuolated; occasionally, subepidermal bullae are present. Melanin pigment and melanocytes are lost from the epithelium. The atrophic dermis is edematous, hyalinized, and sparsely cellular. Sweat glands and pilosebaceous apparatus are absent. Dermal vessels are telangiectatic or obliterated, and there is loss of elastic fibers. A variable number of lymphocytes and plasma cells lie just below the atrophic dermis. Lichen sclerosus is commonly observed in association with intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive SCC (204). Hart et al. (205), however, followed 92 patients with lichen sclerosus for a median follow-up interval of 9 years. The single patient who subsequently developed an invasive SCC initially had coexistent mild intraepithelial neoplasia. In the same series, each of five patients with simultaneous lichen sclerosus and invasive carcinoma had neoplasms which tended to arise in areas of minimal dystrophy or normal vulvar skin. Thus, the relationship between lichen sclerosus and squamous neoplasia is still largely undetermined. However, some recent studies have detected p53 mutations in some cases of lichen sclerosus, suggesting some cases may be part of the pathway that leads to squamous carcinomas of the type not associated with HPV.

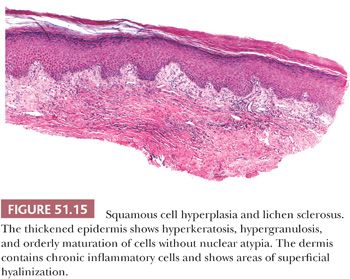

Squamous cell hyperplasia (hyperplastic dystrophy) in most cases is probably caused by chronic irritation (chronic rubbing and the itch–scratch cycle). Many cases likely represent lichen simplex chronicus (130). Squamous cell hyperplasia may be superimposed on other dermatoses and sometimes is observed adjacent to invasive SCC. Approximately 45% to 50% of patients with clinical vulvar dystrophy have squamous cell hyperplasia and 40% have lichen sclerosus (206,207); 10% to 15% of the patients have mixed patterns. Squamous cell hyperplasia may be present adjacent to or remote from lichen sclerosus. Sometimes, squamous cell hyperplasia overlies an atrophic dermis (Fig. 51.15). Some biopsies have foci of dysplasia (6,206,207). Most of these latter cases are likely to be examples of differentiated VIN (see later discussion). If possible, it is important to reserve the poorly descriptive term squamous cell hyperplasia for when a more specific diagnosis cannot be rendered.

Vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesion is a designation promulgated to replace other terms for in situ squamous proliferations of the vulva, including atypia, dysplasia, Bowen disease, bowenoid atypia, bowenoid papulosis, erythroplasia of Queyrat, carcinoma in situ, and carcinoma in situ simplex type (207). Prior to 1970, HSIL was most often noted in women in the fifth or sixth decade of life, but currently about one-half of patients are less than 40 years old. HSIL in young women is frequently multifocal and is associated with HPV infection. Progression to carcinoma appears to be uncommon in this age group (208). The clinical appearance of HSIL is variable. The lesions may be single or multiple and may involve any portion of the vulva. Discrete or coalescent papules or macules are gray, white, red, or darkly pigmented. They may be scaly or eczematoid. Some lesions mimic condyloma grossly. However, most are HSIL (VIN 3) (208,209).

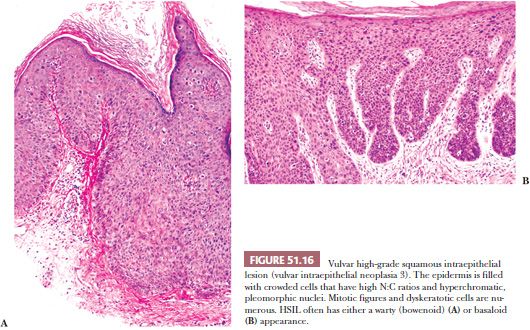

Microscopically, HSIL consists of crowded cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratios; hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei; and increased numbers of mitotic figures (with abnormal forms) (202). Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and dyskeratotic cells often are observed. The dysplastic cells of vulvar flat LSIL (VIN 1/mild dysplasia) are confined to the lower one-third of the epithelium. Mitotic figures are also confined to the parabasal layers. Orderly, mature squamous epithelium is found overlying the dysplastic cells. Unlike condylomata, which are more than 90% HPV-6– and HPV-11–associated, most flat SIL (VIN 1/mild dysplasia) are associated with high-risk HPV types (202).

Differential Diagnosis

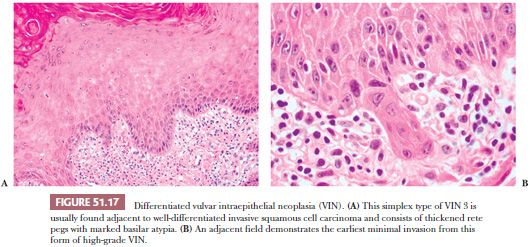

The main differential diagnosis of LSIL (VIN 1) is normal or mildly hyperplastic glycogenated epithelium or other reactive inflammatory conditions. HSIL (VIN 2) contains cells with enlarged, crowded nuclei limited to the lower two-thirds of the epithelium. Cellular maturation is present at the uppermost one-third of the epithelial surface. Mitotic figures (including abnormal forms) and dyskeratotic cells are found in the dysplastic upper cell layers. HSIL (VIN 3/severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ/VIN, usual type) contains dysplastic cells that extend up to more than two-thirds of the thickness of the epithelium (Fig. 51.16). The dysplastic cells often extend into the outer portions of hair follicles. Multinucleated, giant dysplastic cells (bowenoid cells) are frequently seen in vulvar HSIL. In our experience, biopsy sampling variability often demonstrates that most HSIL (VIN 2) lesions actually are associated with HSIL (VIN 3). Hence, for practical purposes, these lesions are grouped as HSIL. Condyloma may be seen adjacent to HSIL or there may be a gradual transition from condyloma to HSIL. Some lesions have features of both HSIL and condyloma (94). HPV type 16 has emerged as the predominant type in vulvar HSIL, although other viral types have been found (106,107). In a study of 67 lesions of HSIL (VIN 3), including both warty (bowenoid) and basaloid (nonbowenoid) types, 90% contained type 16 or 33 by PCR (210). Some examples of simplex or differentiated VIN have cells with copious mature cytoplasm that retain dysplastic nuclei. The dysplastic cells are usually only located in the basilar layers with maturation in the superficial layers. The rete pegs may be thickened and branched, and intraepithelial squamous pearls may be located at their tips (Fig. 51.17) (211). Differentiated or simplex type of VIN is usually found in or adjacent to invasive SCC occurring in postmenopausal women and is not strongly associated with HPV.

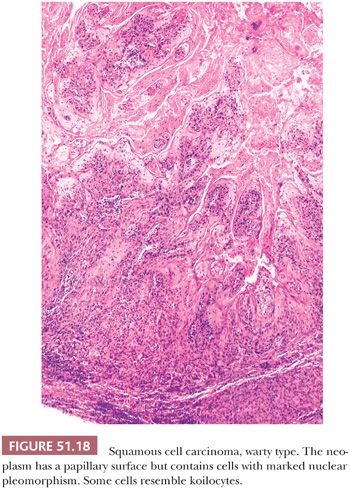

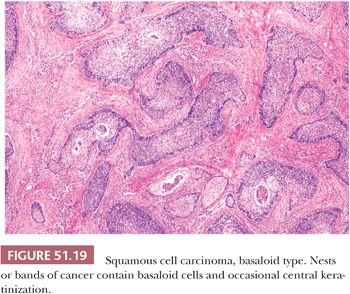

The older dermatologic term bowenoid papulosis (105,212) or bowenoid dysplasia (213), represents a clinical subset of vulvar HSIL in which multiple, small, red-brown papules occur chiefly in young women 20 to 40 years of age. The lesions sometimes are found during pregnancy. Many untreated cases of bowenoid papulosis may regress spontaneously (212,213). HPV type 16 DNA has been documented in bowenoid papulosis (105). Some authors have reported that the cells of bowenoid papulosis show a lesser degree of dysplasia and more maturation than HSIL (VIN 3) (212,213). It also has been noted that bowenoid papulosis tends to involve the acrosyringium and spare the acrotrichium (212,213). In our opinion, the lesions are histologically identical to HSIL except for their relatively small size. Although the natural history of bowenoid papulosis is not completely known, the risk of progression to invasive carcinoma appears to be low. Bowenoid papulosis should not be used as a specific histopathologic term. Vulvar HSIL can be separated into three distinctive types (107,214). Warty (bowenoid) has a condylomatous appearance and often contains HPV type 16 DNA (Fig. 51.18). Basaloid (undifferentiated) has a smooth surface, consists of small cells with little maturation, and shows koilocytotic atypia less frequently (Fig. 51.19). The atypia involves two-thirds or more of the epithelium and is notable for disorganization, cells with high N:C ratios, dark irregular nuclei, and numerous mitotic figures, including abnormal forms. Dyskeratotic cells are often present and the dysplastic cells frequently extend down pilosebaceous units, which can mimic invasive carcinoma. Vulvar HSIL with both warty and basaloid microscopic features has been found in about 20% to 35% of cases (107,214). Pagetoid is rare but important to recognize because it can closely mimic extramammary Paget disease. At the present time, there is no clear clinical need to subtype vulvar SIL (i.e., warty, basaloid, or pagetoid), but simplex/differentiated VIN should be separately identified (see the following section).

Treatment for vulvar HPV-related SIL is usually local excision or laser vaporization of clinically large or symptomatic lesions. Recurrence is common, especially following the latter procedure (209). Approximately one-fourth of women with HSIL (VIN 3) have persistent or recurrent disease after local excision (99,208,215,216); 2% to 10% of women treated for HSIL (VIN 3) develop invasive SCC (95,208,209,215,216). In one study of incompletely excised HSIL (VIN 3), seven of eight patients progressed to invasive cancer within 8 years (216). The presence of invasive cancer results from progression of intraepithelial neoplasia or the development of carcinoma away from the area of HSIL. One-fifth to one-third of invasive SCCs have adjacent foci of HSIL (VIN 3) (204,217). Patients with vulvar HSIL (VIN 3) are at high risk for the development of HSIL or invasive SCC of the vagina and cervix; 20% to 40% of patients with vulvar HSIL (VIN 3) have vaginal or cervical dysplasia or carcinoma (95,215).

Simplex or Differentiated Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia

In contrast to vulvar HSIL, simplex or differentiated VIN typically lacks evidence for HPV and contains dysplastic cells with mature cytoplasm in the basilar layers, occasional pearl formation, and surface maturation (211,214). It occurs usually in older women in or around invasive SCC. In the absence of invasive cancer, it is often problematic to recognize both clinically and histologically. The morphologic attributes of simplex VIN are subtle and consist of expansion of the basal layer into elongated, narrow, branching rete ridges; nuclear atypia of the basal cell layer; and abnormal maturation. The nuclei can range from relatively small, dark, and irregular to less commonly, enlarged, and pleomorphic. Abnormal maturation is characterized by the presence of enlarged keratinocytes with large, pleomorphic nuclei and abundant, markedly eosinophilic cytoplasm in the mid- to superficial layers. These abnormal keratinocytes can extend into the basal layer and involve the rete ridges. The epithelium can be atrophic or acanthotic.

The differential diagnosis for simplex VIN includes lichen sclerosus with squamous hyperplasia and other benign dermatologic conditions such as lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, spongiotic dermatitis, and candida vulvitis.

Treatment for simplex-type VIN is not standardized as there are few recurrence data; however, most are treated by excisional biopsy as opposed to laser vaporization.

MALIGNANT NEOPLASMS

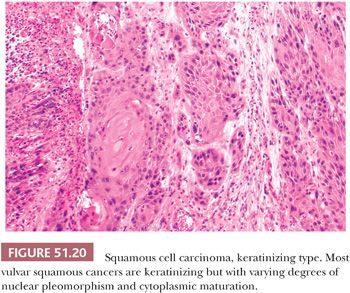

SCC accounts for approximately 90% of all primary invasive vulvar neoplasms. Three-fourths arise on the labia (usually the labia majora), and most of the remainder are located on the clitoris or fourchette (218–220). The age range is broad, but most neoplasms develop in women in the seventh or eighth decade of life (220,221). Very rarely are patients less than 20 years of age. Prior conditions associated with vulvar SCC include HPV infection (96,97,99,106,108,109), lymphogranuloma venereum (61), granuloma inguinale (60,61), immunosuppression (222), and Fanconi anemia (223). Overall, HPV has been detected in about 50% of vulvar SCCs (224). Type 16 has been the predominantly identified papillomavirus (106,108,109). There is evidence that the presence of the virus correlates with specific histologic subsets of invasive cancer (basaloid, warty, and pagetoid), the presence of HSIL, and young patient age (109,211,225). In a study of 100 SCCs, 7% were warty, 28% were basaloid, and 65% were keratinizing (226). Warty carcinomas have a condylomatous appearance because the papillary surface overlies irregular jagged nests of squamous epithelium at the tumor base (Fig. 51.18). Cells with marked nuclear pleomorphism and features resembling koilocytes are present, as well as squamous pearls found in ordinary SCC. Basaloid carcinomas have sheets or bands of small, immature squamous cells with nuclear hyperchromasia and high N:C ratios (Fig. 51.19). Little or no squamous maturation is seen, but occasional abrupt keratin pearl formation may be present. Conventional SCCs, not otherwise specified (NOS), show overt keratinization and squamous pearls (Fig. 51.20). Squamous hyperplasia has been found adjacent to 83% of keratinizing carcinomas, whereas basaloid or warty HSIL has been observed adjacent to 77% of the invasive warty or basaloid cancers (226). Keratinizing cancers occur more often in older women, whereas basaloid and warty types occur chiefly in younger women. Conventional SCCs in older women are much less often virus-related (109,225). In one study, 84% of basaloid or warty carcinomas had HPV type 16 or 33 by PCR, whereas only 4% of the keratinizing SCCs had evidence of the virus (211). There is some evidence that the absence of HPV DNA in vulvar cancers is predictive of an adverse outcome (227). Loss of wild-type p53 function occurs either by interaction with human papillomaviral oncoproteins or by somatic mutation in those vulvar carcinomas that lack papillomavirus (228); the cases with somatic mutation and no HPV may be more aggressive. Many women with vulvar cancer and HPV are at high risk for dysplasia and invasive carcinoma of the cervix and vagina. Hording et al. (206) found that only 2% of women with keratinizing SCC of the vulva developed cervical neoplasia, whereas 40% of those with basaloid or warty types of vulvar carcinomas had cervical dysplasia or carcinoma.

In summary, there are two broad types of squamous cancer of the vulva: One is HPV-associated and evolves from HSIL (usual VIN), and the other, which is more common in older women, is not associated with HPV and has differentiated VIN as its precursor.

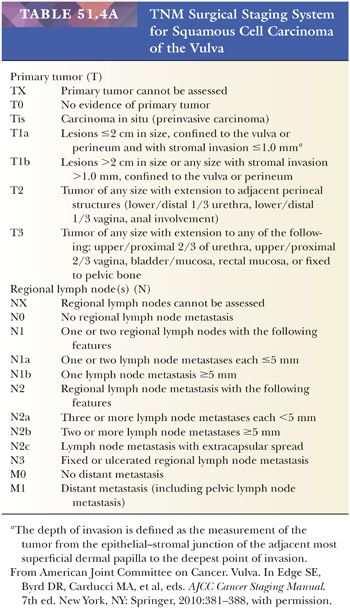

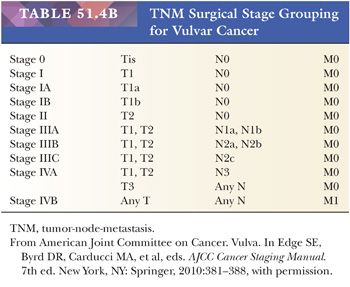

Grossly, SCCs appear as erythematous or white plaques, ulcers, nodules, or fungating, papillomatous growths (221). The important factors in surgical staging include tumor size, extension into surrounding structures, status of the groin and pelvic lymph nodes, and distant metastasis (Tables 51.4A,B) (229). The clinical evaluation of groin lymph nodes is often unreliable. Up to 43% of clinically negative groin lymph nodes contain carcinoma microscopically (230). Conversely, up to 45% of clinically positive inguinal-femoral lymph nodes lack tumor on microscopic examination (221).

Important pathologic factors for vulvar SCC include tumor size, thickness or depth of stromal invasion, grade, pattern of infiltration, vascular invasion, perineural invasion, multifocality, margins of excision, and status of lymph nodes. Although strict criteria for grading have not been well delineated in most studies, the criteria set forth by Broders (228), originally for lip cancer, and Jakobsson et al. (229), for carcinoma of the larynx, generally have been applied. Although the data are conflicting concerning the relationship of tumor grade to groin lymph node status and overall prognosis (230–243), many studies have shown that high-grade tumors more often metastasize to inguinal and femoral nodes, resulting in a poorer outcome (220,221,233–236,241,243,244).

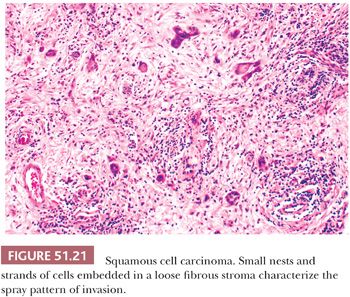

Vulvar squamous cancers either have a broad, pushing, and circumscribed front, or an irregular, infiltrating margin. Tumors with an infiltrating margin may contain dissociated cells or cells forming small, angulated nests or cords that incite a prominent desmoplastic response (diffuse, stellate, or spray pattern) (Fig. 51.21) (233,237,240,245,246). Such neoplasms, even those that are small and superficially invasive, have a proclivity for lymph node metastasis. Confluent growth is a poorly defined term that often refers to an amount of tumor filling at least 1 mm of a microscopic field (234,237,238). It primarily correlates with tumor thickness and depth of stromal invasion. The use of the term confluent should be discouraged. Patients with squamous cancers having a marked lymphocytic stromal response may have a better prognosis than those whose tumors incite a minimal lymphoplasmacytic reaction (221,240). On the other hand, patients with tumors exhibiting a prominent fibromyxoid stromal response have been reported to have a poorer survival rate and more extensive lymph node metastasis than do those with neoplasms lacking this stromal feature (247). Such neoplasms with a conspicuous fibromyxoid stromal reaction are most often clitoral, flat or elevated, ulcerated, and occur in older women.

The presence of vascular permeation clearly increases the risk for nodal metastasis (234,235,237,240,244,248,249). Using multiple step sections, Donaldson et al. (249) found capillary permeation in 34% of tumors, which had less than 5 mm of stromal invasion, and in 71% of neoplasms, which had more than 5 mm of stromal infiltration; 79% of their patients with vascular invasion had inguinal lymph node metastases, as compared with only 6% of patients whose tumors lacked invasion. For stage I carcinomas, Iversen et al. (248) found that 6 of 15 tumors with vascular invasion metastasized to lymph nodes, whereas only 2 of 61 that lacked vascular permeation metastasized. The 5-year survival rate for their patients whose tumors lacked vascular invasion was 85%, compared with 52% survival for patients having neoplasms with vessel invasion (248). Some data indicate that perineural invasion, perhaps even more strongly than other histologic features of the primary lesion, is strongly predictive of lymph node metastasis (250).

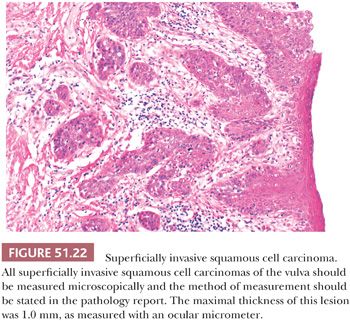

Microinvasive, superficially invasive, and early invasive are descriptions that have been used for SCCs, which are thin and have small amounts of stromal penetration (Fig. 51.22). Historically, these terms have not been applied uniformly. By analogy to cervical cancer, all are used to try to define cases of invasive squamous cancer at exceedingly low risk for nodal metastasis that can therefore be treated conservatively. Franklin and Rutledge (241) initially defined microinvasive SCC as a tumor 2 cm or less in diameter with 5 mm or less of stromal invasion; 3 mm (234,239) and 1 mm (251) have been used more recently as upper limits for stromal invasion. Currently, superficially invasive tumors (equivalent to microinvasive) are defined as confined to the vulva or perineum, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension, and having 1 mm or less of stromal invasion (202). The depth of invasion is defined as the measurement of the tumor from the epithelial–stromal junction of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion. In a literature review, Wilkinson (252) found that 15% of tumors with stromal invasion of 5 mm or less metastasized to groin lymph nodes, whereas 12% of tumors that invaded to a depth of 3 mm or less resulted in nodal metastases. In a large study of 272 women with superficial SCC, 3% of tumors (1 of 32) that were less than 1 mm thick (as measured with a ruler on the microscopic sections), 19% of those that were 3 mm thick, and 33% of neoplasms that were 5 mm thick metastasized to groin lymph nodes (253). Nodal metastases also occurred more frequently in SCCs, which were poorly differentiated, had capillary-like space involvement, or had a clitoral or perineal location. Each of the preceding factors showed a statistically significant correlation with groin lymph node metastasis in a multivariate analysis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree