•Symptomatic patients with >70% stenosis

•Symptomatic patients with 50% to 69% stenosis, with ulceration or when all other sources (i.e., cardiac embolus) have been ruled out

•Asymptomatic good medical risk patients with >80% stenosis

Carotid Disease

•Can present as a transient ischemic attack (TIA)

•A neurologic event that resolves completely within 24 hours

•Symptoms that last >24 hours constitute a stroke, which requires further brain imaging

•Timing of CEA

•Proceed when residual symptoms stabilize or resolve completely

•An immediate CEA is indicated for a “crescendo” or evolving TIA/cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (frequent, worsening, or fluctuating neurological findings)

•The traditional 6-week delay may only be necessary in patients with a large, disabling CVA

•An endarterectomy with patch angioplasty (autogenous vein or prosthetic patch) leads to better outcomes than primary arterial closure

•An eversion endarterectomy may have similar outcomes

Carotid artery plaque. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Complications of Carotid Endarterectomy

•Airway compression from an expanding hematoma

•Vagus nerve (laryngeal branch) injury causes vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness

•Hypoglossal nerve injury causes tongue deviation toward the side of surgery

•Any postoperative dyspnea or change in neurologic exam warrants emergent re-operation

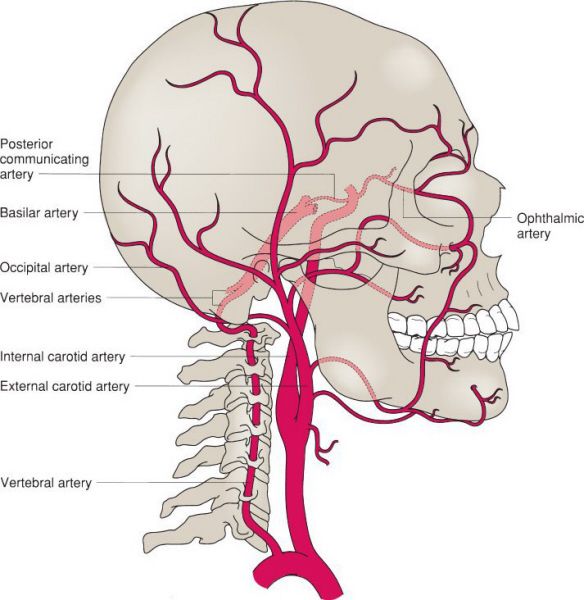

Amaurosis fugax (transient monocular blindness) results from an embolus to the ophthalmic artery, a branch of the internal carotid artery, and is an indication for CEA.

A 76-year-old man with a significant cardiac history presents with a left hemispheric TIA. He has had a previous left CEA in the remote past and a carotid duplex now shows a critical (80% to 99%) recurrent stenosis. How should this be managed?

Consider a left carotid angioplasty with stenting using an embolic protection device.

Normal carotid and vertebral artery anatomy. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting

•Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) is restricted to:

•High-risk symptomatic patients <80 years of age with ≥70% stenosis

•High-risk symptomatic patients <80 years of age with 50% to 70% stenosis

•High-risk asymptomatic patients <80 years of age with >80% lesions

•High anatomic/surgical risk factors

•Redo carotid intervention

•Radiation-induced stenosis

•Prior radical neck dissection

•A surgically inaccessible lesion (above C2)

•Common carotid lesion below clavicle

•Contralateral vocal cord palsy

•Contralateral internal carotid occlusion

•Tracheostomy

•Embolic protection with either a balloon, filter, or reversal of flow device is needed

•CT angiography with 3D reconstruction is useful to delineate the aortic arch and carotid anatomy for procedural planning

Angiogram demonstrating an isolated atherosclerotic lesion. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•Pre-procedure loading with clopidogrel for 7 to 10 days and continued therapy for at least 30 days post-intervention is recommended

•Anatomic challenges to performing a CAS include difficult arch anatomy (i.e., elongated, tortuous, and/or diseased arch; bovine arch), significant common carotid disease, heavily calcified lesions, and a tortuous internal carotid artery

•A redo CEA is considered in these situations but often requires interposition grafting and has a higher risk of cranial nerve injury

Carotid stenting should be considered in symptomatic patients (>50% stenosis) or asymptomatic patients (>80% stenosis) if they have medical problems or anatomic abnormalities that make them high risk for CEA.

A 35-year-old man with a past medical history of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome presents with new-onset headache, neck pain, Horner’s syndrome, and amaurosis fugax of the left eye. What is the diagnosis and best initial management?

The patient had a spontaneous carotid dissection. Anticoagulation is the first-line treatment for most extracranial carotid artery dissections. He should then be followed with serial duplex ultrasound exams.

Carotid Artery Dissection

•Presents with ipsilateral neck pain and embolic symptoms in patients with collagen vascular disorders

•May be spontaneous (60% to 70%) or traumatic (30% to 40%)

•Duplex ultrasound may be a reasonable first diagnostic test and can often identify a flap or thrombus just distal to the carotid bulb with highly resistive waveforms

•The diagnostic gold standard is arteriography; however, noninvasive imaging with MR or CT angiography is often adequate to make the diagnosis while also providing axial imaging to rule out hemorrhage

•The classic radiographic finding is a tapered stenosis or occlusion of the internal carotid artery associated with an aneurysm at the base of the skull

•The treatment for a patient with spontaneous dissection with minimal or no neurological deficits is anticoagulation (acutely with unfractionated heparin; long term with warfarin) and antiplatelet therapy (ASA)

•Surgery or percutaneous intervention

•Considered in patients with active ongoing symptoms or with a contraindication to anticoagulation

•Depends on the location and extent of the dissection

•Can perform interposition grafting, ICA ligation, or EC-IC bypass

•Often challenging and fraught with complications in patients with collagen vascular disorders

Most carotid dissections recanalize and heal completely within a few months of initiating anticoagulation therapy and do not require surgical intervention.

A 43-year-old Caucasian female undergoes evaluation following two episodes of TIA. Cerebral angiography reveals a “string of beads” appearance of the internal carotid arteries bilaterally. What is the most likely diagnosis?

A “string of beads” appearance on the arteriogram of a young or middle-aged woman is characteristic of fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD).

Fibromuscular Dysplasia

•Typically affects Caucasian women (~90%) in the 4th or 5th decade of life

•Bilateral in 65% of cases

•Associated with intracranial aneurysms in 10% to 50% of cases

•Pathology shows medial fibroplasia in 80% to 95% of cases

•Approximately 10% of cases are symptomatic and present with TIA, stroke, or amaurosis fugax

•Diagnosis can be suggested by duplex ultrasound, CT, or MR angiography, but is confirmed by arteriography, particularly if intervention is warranted

•Asymptomatic patients are treated with antiplatelet therapy, monitoring for hypertension, and evaluation for the presence of an intracranial aneurysm

•Surgical options in symptomatic patients include open graduated internal dilatation and open balloon angioplasty

•Renal FMD

•Occurs in 8% to 40% of patients with carotid FMD

•Overall more common and typically presents with hypertension

•May require initial or simultaneous treatment with percutaneous angioplasty alone (without stenting) to prevent complications of hypertension

FMD can involve the renal, carotid, external iliac, splenic, hepatic, vertebral, or axillary arteries.

A 69-year-old man with an incidental finding of a 4.3-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) presents to the office. He has no complaints and a normal physical exam. What is the next step in his management?

Repeat the CT scan in 1 year or repeat an ultrasound in 6 months to assess the growth of the aneurysm. In the meantime, provide counseling regarding the typical symptoms related to an AAA.

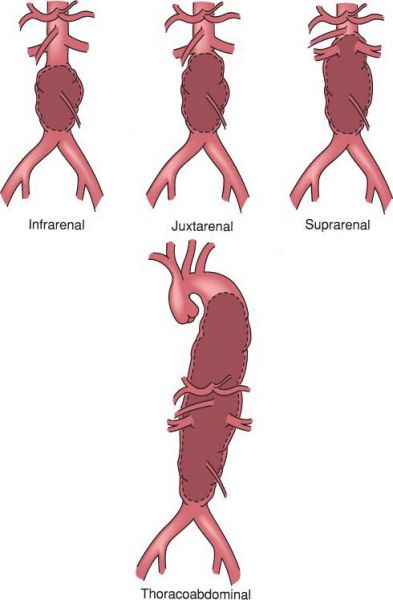

Types of abdominal aortic aneurysms. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

•Most commonly found in the infrarenal aorta

•Results from degeneration of the wall with loss of elastin and weakening of collagen

•Most commonly secondary to atherosclerosis

•Average growth rate of approximately 10% per year

•Most are asymptomatic and found incidentally on abdominal imaging

•May also present as back/abdominal pain or an abdominal mass on examination

•Risk of rupture (per year)

•<5 cm: 1% to 4%

•5 to 6 cm: 5% to 8%

•6 to 7 cm: 8% to 15%

•7 to 8 cm: 15% to 30%

•>8 cm: 30% to 50%

•Indications for elective repair (either endovascular or open) are diameter >5.5 cm, presence of symptoms, or growth >1.0 cm/year or 0.5 cm in 6 months

•Open repair can be accomplished through either an anterior or retroperitoneal approach and involves either a tube graft or bifurcated aortobiiliac repair (generally if iliac arteries are >2.5 cm)

•Impotence is a common complication of an open repair (>30%)

•Endovascular repair ideally requires

•Neck diameter ≤32 mm

•Neck length >10 mm

•Neck angulation ≤60 degrees

•Common iliac diameters ≤20 mm

•External iliac diameters ≥7 mm

•Endovascular repair has a lower short-term morbidity and mortality compared to open repair, but mortality is equal at 2 years

•As with most vascular procedures, cardiac complications are the most common cause of perioperative morbidity and mortality

•Cardiac and renal complications are the most common cause of death beyond 30 days postoperatively

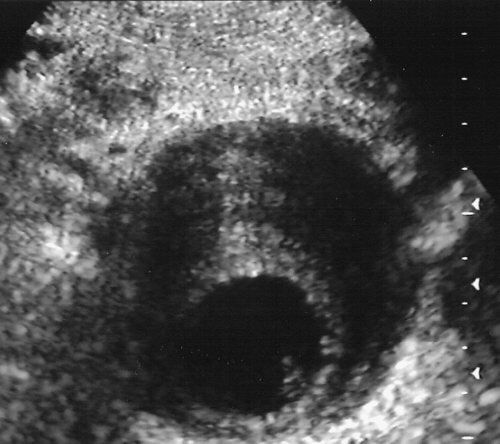

Ultrasound of an AAA. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

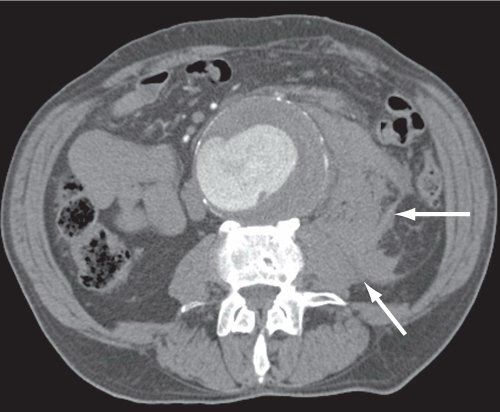

Large abdominal aortic aneurysm. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Screening is now approved for AAA in populations at risk (i.e., males >55 years old who have ever smoked, and men or women >55 years old with a family history of aneurysms).

A 75-year-old man with a history of hypertension presents to the emergency department with acute-onset severe abdominal and lower back pain. His physical exam reveals a markedly distended and diffusely tender abdomen. His vital signs on presentation include a blood pressure of 70/40 mmHg and a heart rate of 130 bpm. Two large-bore IVs are in place. What should be the next step in management?

A high suspicion for a ruptured AAA necessitates an emergent exploration. As with any unstable patient with a surgical abdomen, a CT scan should not delay operative exploration.

Ruptured AAA. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

•The classic triad of signs/symptoms include severe acute abdominal and/or back pain, hypotension, and a pulsatile abdominal mass

•95% of cases will demonstrate at least one of these three findings

•<50% will have all three findings

•Operative mortality is approximately 50%, while overall mortality from a ruptured AAA is historically approximately 80%

•Proximal control can be achieved by incising the diaphragmatic crus to expose and clamp the supraceliac aorta

•A nasogastric tube is essential to help distinguish the aorta from the esophagus at this level

•The most common location for rupture is the left retroperitoneum below the renal vessels

•Most emergent cases can be managed with a tube graft repair

•If the patient is stable enough on presentation to permit a CT scan, the anatomy can be evaluated for endovascular repair

•Endovascular repair, when appropriate, is feasible and may reduce operative mortality rates to 20% to 30%

•Postoperative management should focus on resuscitation, monitoring for postoperative hemorrhage, and aggressive management to prevent renal failure

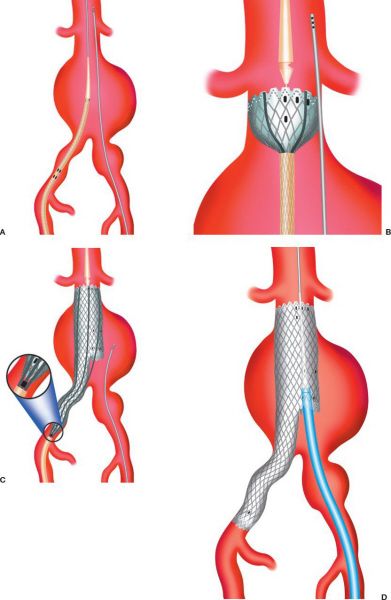

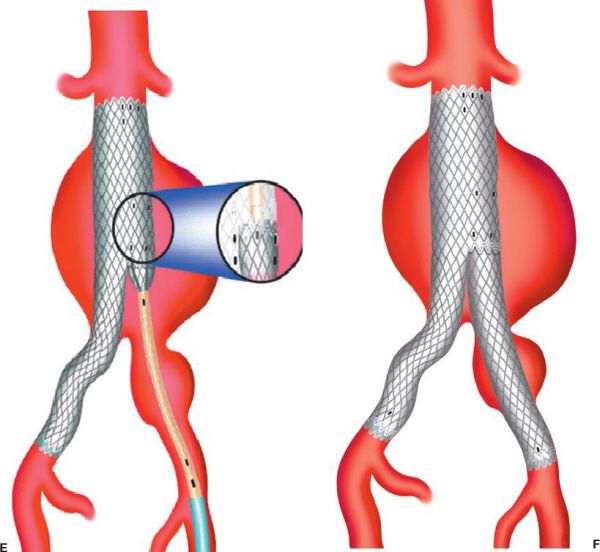

Endovascular repair of an AAA. (A) insertion of aortic endograft. (B) initial graft deployment at levels of renal arteries. (C) completion of main body device with ipsilateral limb. (D) insertion of contralateral limb component. (E) placing contralateral limb. (F) completed deployment. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

A retroaortic left renal vein is an anatomic variation that is susceptible to injury during aortic exposure and cross-clamping during an open AAA repair.

A 77-year-old male presents with a pulsatile abdominal mass, weight loss, and generalized malaise. A physical exam reveals a widened abdominal aorta, measuring approximately 6 cm in size. Laboratory data are all normal except an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. What is the diagnosis and how should you proceed from here?

An inflammatory AAA should be evaluated with a CT scan, followed by surgical repair.

Inflammatory Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

•Characteristic enhancing rim around the aortic wall (signet ring appearance) on CT scan

•Not caused by an infectious organism

•Most common in males in the 7th decade of life

•Presents with abdominal pain, weight loss, myalgias, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

•The inflammatory reaction often involves adjacent structures (duodenum (>90%), ureters, vena cava, and left renal vein), complicating dissection, and open repair

•Repair is typically via an open retroperitoneal approach; however, growing experience with endovascular repair shows promise for technical feasibility with prompt resolution of inflammation and associated symptoms

•The inflammatory process resolves after graft placement

A retroperitoneal approach is advantageous for repair of inflammatory aneurysms to avoid injury to the duodenum and other adjacent structures.

On postoperative day one following an aortic aneurysm repair, a 63-year-old female is noted to have melena. What is the next step in management?

In the early postoperative period following an aortic aneurysm repair, any patient with bloody or melanotic stool, or severe diarrhea requires an immediate rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy. Broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and fluid resuscitation should also be started for presumed ischemic colitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree