Renal calculi. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Urinary Calculi

•Calcium stones (calcium oxalate + calcium phosphate) are the most common type (70%)

•Associated with hyperparathyroidism, hyperoxaluria

•Treat with hydration or management as below for larger stones

•Staghorn calculi are large, infected renal calculi

•Composed of Mg–ammonium phosphate (struvite) and Ca phosphate

•Due to infection with urease-producing bacteria (Proteus mirabilis)

•Forming the renal calyx and pelvis as a branched staghorn

•Treatment: Antibiotics and hydration

•Cystine stones

•Caused by defect in transport of cysteine

•Treatment: Hydration, urine alkalinization

•Associated with gout, Lesch-Nyhan (high purine turnover), myeloproliferative disorders

•Treatment: Hydration, urine alkalinization

•90% of stones are radiopaque and seen on KUB X-ray

•Uric acid stones are radiolucent

•Manifestations of stones

•Asymptomatic (non-obstructive renal stones)

•Flank pain: Colicky flank pain that radiates to the lateral abdomen (proximal ureteral stones) or pain that radiates into the groin and genitals (distal ureteral stones)

•Microscopic or gross hematuria

Obstructive pyelonephritis/sepsis

Treatment of Urinary Calculi

•Ureteral stones at three distinct points:

•The ureteropelvic junction (UPJ)

•The pelvic brim where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels

•The ureterovesical junction

•Most stones (90%) are less than 4 mm in diameter and pass spontaneously

•Stones less than 4 to 5 mm can be observed to see if they will pass spontaneously

•Hydration, analgesia, and urine straining constitute expectant management

•Larger stones are less likely to pass (>7 mm stones have about 20% to 30% chance of passing)

•Non-obstructive renal stones less than 2.5 cm can be managed by extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy

•Larger renal stones require percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

•Staghorn calculi require percutaneous removal

•Surgery is indicated in patients for:

•Severe pain not controlled with oral analgesia

•Complete obstruction of a solitary kidney

•Large stones with obstruction, infection, and hydronephrosis

•Surgical options include: Cystoscopy with stent placement, ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy, and PCNL

White blood cell casts are a marker of pyelonephritis or glomerulonephritis

A 58-year-old male presents to clinic with new-onset painless, gross hematuria. He does not have symptoms of dysuria, urgency or frequency. His past medical history is significant for tobacco use for 30 years and hypertension. He takes metoprolol and has no drug allergies. His physical examination is notable for a 20 cc prostate that is benign to palpation. His last PSA was 0.3. What is the next step in management?

A CT scan with IV contrast, cystoscopy, and urine cytology should be performed to evaluate the patient for bladder cancer.

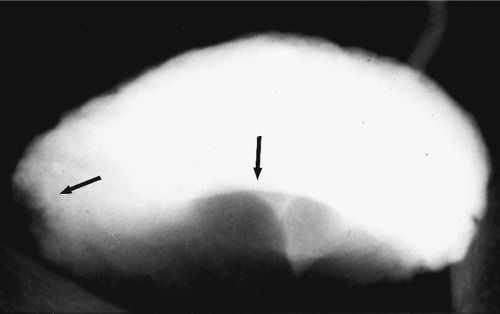

IVP demonstrating bladder filling defect in a patient with bladder cancer. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Bladder Cancer

•Painless gross hematuria is the most common presentation

•Other presentations include microscopic hematuria and irritative voiding symptoms

•Risk factors include cigarette smoking, age, and exposure to aniline dyes, cyclophosphamide, and phenacetin

•Cigarette smoking is strongly associated with bladder cancer

•Transitional cell carcinoma (>90%)

•Squamous cell carcinoma (5% to 7%, associated with Schistosomiasis and chronic infections)

•Adenocarcinoma/urachal carcinoma (1% to 2%)

•Multifocal disease can affect the entire urothelium (renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, and urethra)

•Disease does not usually progress in a step-wise pattern from papillary to muscle invasive

•Obtain urine cytology, cystoscopy, and an upper tract evaluation with a CT scan or IVP

•Perform a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) for tissue diagnosis

Treatment of Bladder Cancer

•Superficial bladder cancer and carcinoma in situ (CIS) can be treated with:

•Intravesical chemotherapy with Mitomycin C

•Intravesical immunotherapy with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), a live attenuated strain of mycobacterium

•Perform a radical cystectomy with urinary diversion for:

•BCG failure in CIS

•Muscle-invasive disease

•Urinary diversion commonly utilizes the ileum for creation of a neobladder (attached to the native urethra) or an ileal conduit with a urinary stoma

•Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be attempted to downstage tumors from unresectable to resectable

•Chemotherapy is used for advanced disease

•50% of patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer will progress to metastatic disease even after curative local therapy

For bladder cancer that has not invaded the muscle, TURBT and BCG is the initial therapy. Cystectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are reserved for cases with muscular invasion.

Six hours following a TURP procedure for bladder cancer, a patient is found in the recovery room to be having seizures. What is the most likely etiology?

Hyponatremia secondary to copious bladder irrigation (post-TURP syndrome). Airway protection should be the first priority in any seizure patient. Management should then focus on correcting the hyponatremia.

Post-transurethral Resection of the Prostate Syndrome

•Hyponatremia following any procedure with bladder irrigation

•Can manifest as seizures/cerebral edema

•Treated by correcting hyponatremia (but not too rapidly to avoid central pontine myelinolysis)

A 45-year-old female presents with an incidentally discovered 6 cm renal mass on a CT scan. The mass enhances with IV contrast. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Renal cell carcinoma. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Renal Masses

•A solid renal mass with negative Hounsfield units usually represents fat/angiomyolipoma

•A solid renal mass with positive Hounsfield units (enhancing post contrast) is most commonly RCC

•A simple cyst is benign, round, smooth, and thin walled

•Simple cysts typically are low density (−20 Hounsfield units) and have no contrast enhancement on CT

•No treatment is required

•A complex renal cyst should be considered suspicious for malignancy

•Suspicious features include internal septations, calcium deposits, an irregular wall, and areas of contrast enhancement

•Non-renal cancers can metastasize to the kidney (breast is most common)

All complex cysts with any suspicious features should be removed.

Renal Cell Carcinoma

•Occurs in “younger” adults (40 to 60 years of age)

•Greater than 50% of RCCs are detected incidentally

•The classic presentation triad is pain, hematuria, and flank mass

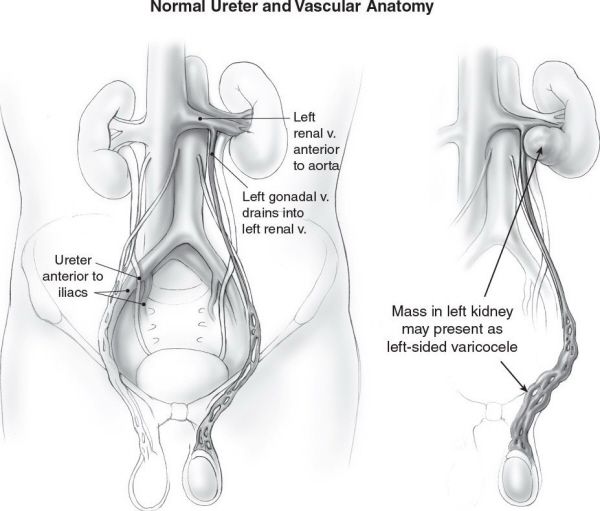

•Other presenting signs and symptoms include pain, weight loss, fever, erythrocytosis (secondary to increased erythropoietin levels), left-sided varicocele, and hypertension

•Paraneoplastic syndromes are present in 20% of patients with RCC

•Hypercalcemia

•Hypertension

•Polycythemia

•Stauffer syndrome

•Nonmetastatic hepatic dysfunction

•Seen in up to 20% of cases

•Lab tests reveal elevated alkaline phosphatase, prothrombin time, bilirubin, and transaminases

•Need to rule out liver metastases

•Hepatic function normalizes after nephrectomy in 60% to 70%

Treatment of Renal Cell Carcinoma

•Treatment is radical nephrectomy including removal of Gerota’s fascia and regional lymph nodes

•RCC can directly extend into the renal vein, up the IVC, and into the atrium—cancers going up into the IVC can still be resected

•An isolated lung or liver metastasis should be resected

•Partial nephrectomy (renal sparing surgery) can be used for small peripheral lesions or in patients with solitary kidneys or bilateral tumors

•Surgery can be performed open, laparoscopic, or robotic

A left-sided varicocele can be a presentation of a left renal cell cancer since the left gonadal vein drains directly into the left renal vein.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree