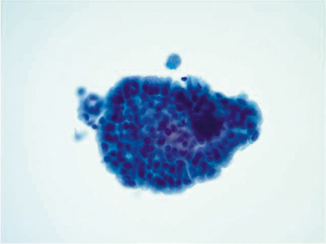

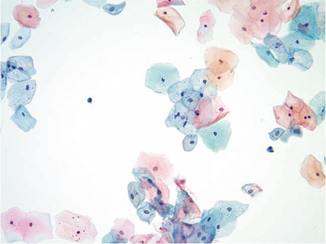

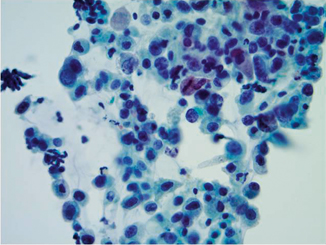

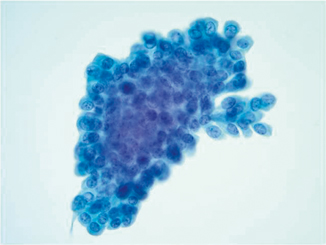

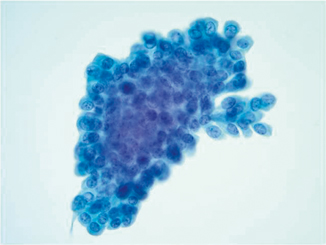

Fig. 21.1

Pap stain 20×. Bladder washing specimen obtained from a patient with a history of urothelial CIS. The instrumentation effect from the washing may slough off epithelial fragments and give them a papillary appearance. These clusters should not be overcalled as low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. One should search for high-grade features

Postcystectomy patients present special consideration for urine cytology , as ileal conduit, bladder augmentation, and urethral washings are used for surveillance. In cases where there is a neobladder or ileal conduit, there may be abundant acute inflammation as well as organisms native to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract such as Candida species. Searching for neoplastic urothelial cells may be more difficult due to obscuring inflammation and bacterial colonies [12]. The utility of urine cytology in ileal conduit specimens has come into question, as atypical cells present in these specimens have poor positive predictive value in detecting recurrent urothelial carcinoma [13].

Adequacy in urine cytology is somewhat controversial. Although some samples are paucicellular, the cellularity of a voided urine sample is beyond the control of the provider. Normal urine has few urothelial cells and a clean background with few leukocytes. Squamous cells may be present in men and women from squamous metaplasia of the trigone or contamination from the urethra. A paucicellular sample in a symptomatic patient should be reported as limited cellularity. An overabundance of bacteria or blood may inhibit interpretation [14].

Clusters of urothelial cells in urine cytology can be attributed to the presence of bladder calculi, low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, or instrumentation effect, such as catheterization (Fig. 21.2). Correlation of the cytologic findings with the cystoscopy report with special attention to the presence of tumor, tumor size, and multifocal lesions increases the sensitivity for finding low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma [15].

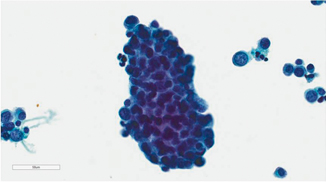

Fig. 21.2

Pap stain 40×—Urine sample from a patient who was paralyzed in a motor vehicle accident who subsequently had long-term indwelling catheterization. The cells show columnar morphology with stratification and mucin formation. The histology showed cystitis cystica et glandularis

Normal Urine

Urothelial mucosal cells exhibit a wide morphologic spectrum. Superficial umbrella cells have one or more nuclei and may measure between 20 and 30 µm in diameter. Multinucleated cells are common, and these cells may raise alarm in urine cytology interpretation. A low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and an absence of nuclear hyperchromasia indicates the presence of benign umbrella cells. The cytoplasm can be hard, dense, and solid similar to the cytoplasm of squamous cells, but may also exhibit vacuolization and granularity.

Cells from beneath the umbrella cell layer are comprised of smaller single cells in the urine. They usually contain a single round nucleus measuring between 8 and 10 microns with a smooth nuclear contour. The cytoplasm is thick and exhibits a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. These cells resemble parabasal squamous cells from the cervix in that they are round to almost ovoid with a basophilic cytoplasm. Under more reactive conditions such as inflammation, the chromatin will become more open and contain 1–2 micronucleoli.

The presence of squamous cells in urine can pose a diagnostic challenge. Most squamous cells in the urine are usually present as contamination from squamous-lined mucosa from the gynecologic tract in females, or penile urethra in males. Less commonly, these cells may arise from the squamous metaplasia of the bladder trigone, especially if the patient is in a state of urinary stasis, or has a history of an indwelling urinary catheter (Fig. 21.3). In patients with urothelial carcinoma, the presence of atypical squamous cells may be associated with urothelial carcinoma with squamous features, or invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 21.4) [16].

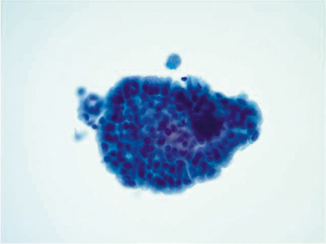

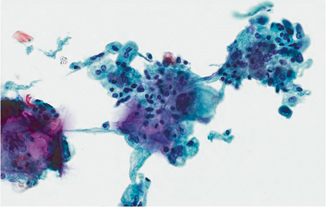

Fig. 21.3

Pap stain 20×. This is a normal urine sample with abundant benign squamous cells in a 72-year-old male. These squamous cells could arise from urethral contamination or squamous metaplasia of the bladder trigone

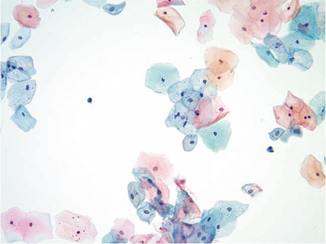

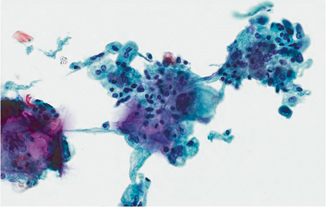

Fig. 21.4

Pap stain 40×—Squamous differentiation in high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. The orangeophilic cell with the elongated, hyperchromatic nucleus may occur in squamous cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation, or high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Correlation with biopsy findings is needed

The background of the normal urine can contain squamous cells, bacteria, blood, and inflammatory cells. These features in the background are not essential to the diagnosis, nor are they necessarily in concordance with the patient’s clinical picture. Acute inflammation may not correspond to an acute cystitis. However, reporting of these features may help the clinician explain some of the clinical findings. Patients with urinary stasis may have abundant acute inflammation. An immunocompromised patient with anucleated squames may have malakoplakia.

Bacteria

Bacterial colonies present in urine typically consist of gram negative rods, usually from bacteria native to the colon. When present, they are usually associated with mixed acute and chronic inflammatory cells and macrophages. Urine cytology is neither a sensitive nor specific means of detecting bacterial infection. Urine dipstick analysis and culture are more suitable.

Fungi

Fungal organisms affecting the bladder can be seen in the urine and usually consist of Candida species. Overgrowth of many Candida organisms may be present in patients with a urinary fungal infection; however, samples left in containers for a long period of time may also grow abundant Candida. Correlation with the clinical picture is necessary. Cystectomy patients with urinary conduits have Candida but these are normal flora from the gastrointestinal tract. Dimorphic fungi ( Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Coccidioides) are rarely present in the urine and are associated with granulomatous inflammation. The specific organism is dependent on the geographic residence or travel history of the patient. The main fungal diagnostic value in urine specimens lies in analysis for polysaccharide detection of Histoplasma antigen [17].

Viruses

Viral organisms can cause significant cytologic changes in the form of viral cytopathic effect. HPV viral changes can be present in the form of contamination from squamous mucosa, HPV changes present in squamous metaplasia of the bladder trigone, or in urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation [18, 19]. Herpes simplex can cause nuclear molding, multinucleation, and margination of the chromatin to give the classic “ground glass” appearance [20]. The bizarre cytopathic changes should be recognized to prevent misdiagnosis of malignancy. Cytomegalovirus inclusions can be seen in immunocompromised (e.g., HIV, transplant) patients and contain large cells with large blue intranuclear inclusions. Polyoma virus is the most common virus seen in urine cytology. Cells infected with this virus have characteristic viral inclusions showing nuclear enlargement, margination of the nuclear material around the nuclear membrane, and a disorganized cobweb-like stranding of the nuclear material [21]. Ancillary techniques are available including the SV40 immunocytochemistry stain as well as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the BK virus [22–24]. The viral load of the blood can be detected and correlated with the BK viral inclusions in the bladder [25]. While these are often found in transplant patients, they can be present in any type of immunocompromised patients, and rarely, in immunocompetent patients [26].

Malignant Changes in the Urine

Urine cytology has low sensitivity (35 % on meta-analysis) and high specificity (99 %) for detecting high-grade urothelial carcinoma (in situ or invasive) [27]. Urothelial carcinoma cells in the urine are enlarged, have a decreased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, are hyperchromatic, and show nuclear irregularity (Figs. 21.5 and 21.6) [28]. Absence of any of these features would lead to a diagnosis of suspicious for urothelial carcinoma. Clinical information provided by the cystoscopy report, for example, the presence of a bladder mass or erythematous areas further strengthens the diagnosis. Unfortunately, this information is sometimes unavailable and may leave a diagnostic void [28].

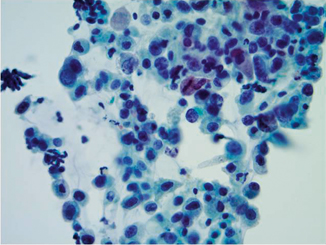

Fig. 21.5

Pap stain 40×—High-grade urothelial carcinoma with nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, anisonucleosis, and increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Whether this patient has urothelial carcinoma in situ or invasive, high-grade urothelial carcinoma must be determined with bladder biopsies

Fig. 21.6

Pap stain 40×—Papillary high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Similar nuclear features to Fig. 21.5. Cystoscopy revealed papillary lesions and biopsy confirmed invasive high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

Atypical diagnoses are frustrating for clinicians. Many etiologies could cause cytologic atypia, including presence of bladder calculi, inflammation, chemotherapy for another neoplasm, or radiation of the prostate or rectum for carcinoma (Fig. 21.7). A diagnosis of atypical is more worrisome in upper tract specimens as compared to lower tract samples and should be more thoroughly investigated [29].

Fig. 21.7

Pap stain 40×. Radiation cystitis in a patient with a history of adenocarcinoma of the prostate treated with radiation. Note the multinucleation and marked cytomegaly while maintaining a normal nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio

Upper Urothelial Tract Carcinoma

Samples of the upper urothelial tract are usually obtained by bladder washing. Upper tract specimens carry their own set of diagnostic and clinical management dilemmas as they are harder to visualize. Endoureteroscopy is necessary to fully visualize the ureters. Retrograde pyelography and CT urograms in conjunction with upper tract samples are useful in detecting urothelial carcinoma [30]. Biopsies of the ureter are difficult since they are usually performed through a very thin instrument. As a result, ureteral cytology may often be the key to the diagnosis.

Ureteral cytology specimens can, however, prove diagnostically challenging . They can be subject to overinterpretation, particularly when obtained from patients with a previous stent for obstruction. Reactive urothelial atypia and clusters are more prevalent in these specimens due to contact with the stent which leads to reactive epithelial changes. In addition, cancers of the bladder may detach and wash into the ureter, rendering a false positive result [15, 31]. It is important to be cognizant of the presence of a prior bladder cancer when interpreting ureter specimens. When evaluating a ureter specimen it is extremely helpful to the cytologist if bladder urine and bilateral ureter samples are provided. Bilateral examination may allow for comparison between the normal and atypical samples. Malignant-appearing cells in one ureter and negative findings in the contralateral ureter with correlating clinical and radiographic information would substantiate a diagnosis of positive for malignancy. However, if atypical/malignant-appearing cells are present in both ureter specimens and a bladder urine sample, contamination by bladder UC may cause a false positive diagnosis.

Detection of low-grade cytology is difficult in urine cytologic specimens. As mentioned previously, clusters of bland-appearing urothelial cells are seen in instrumentation effect or stones (Fig. 21.8). Even in patients with cystoscopic evidence of a low-grade papillary neoplasm, the urine cytology may not correspond to the tumor load [15]. Papillary clusters with true vascular cores may indicate the presence of a low-grade papillary carcinoma if it is in concordance with the cystoscopy report [15, 32].

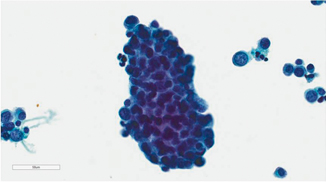

Fig. 21.8

Pap stain 40×—Low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma in a patient who had small papillary lesions. He underwent transurethral resection of the tumor and had urine cytology collected prior to the procedure. No definitive vascular core is present and the cells do not have high-grade morphology. These cells are nearly identical to those found in an instrumented urine specimen

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree