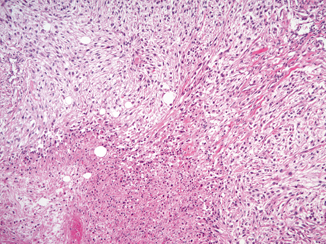

Fig. 25.1

Clear cell carcinoma with coagulative tumor necrosis. True coagulative tumor necrosis, in contrast to hyalinized areas of scarring and regression often seen in clear cell RCC, consists of necrotic “ghost” cells with associated nuclear and cytoplasmic debris

Recognition of the importance of tumor necrosis was reflected in the recommendations of the 2012 ISUP consensus conference. It was agreed upon by consensus that for clear cell RCC, the presence or absence of tumor necrosis should be included in pathology reports, that assessment should include both macroscopic and microscopic examination, and that the amount of necrosis present should be included as a percentage [11]. In practical terms, however, quantifying necrosis can be a somewhat subjective exercise that is limited by sampling technique and not universally practiced; at our respective institutions, we do not generally submit sections containing only grossly necrotic tumor and do not currently quantitate necrosis, grossly or microscopically.

Sarcomatoid Differentiation

Sarcomatoid differentiation in RCC, recognized as a malignant spindle cell component resembling a sarcoma, is no longer thought to define a distinct subtype of RCC. Rather, it is thought to represent a common pathway of tumor dedifferentiation that can occur in any RCC subtype. Sarcomatoid differentiation in RCC has been demonstrated repeatedly to be associated with aggressive behavior independent of other pathologic parameters; patients with sarcomatoid differentiation have frequent metastases, often at the time of presentation, and short survival (median 6–19 months) [12–14]. In some studies, a higher percentage of sarcomatoid differentiation has been associated with decreased survival [12, 14]. The parent subtype of RCC does not appear to have prognostic significance once sarcomatoid differentiation has occurred [12, 13, 15], although one recent study suggests that patients with metastatic sarcomatoid carcinoma arising in association with clear cell RCC may have a better response to vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGF)-targeted therapy [16].

Grossly, areas of sarcomatoid differentiation are often seen as dense, tan to white fleshy areas with infiltrative borders, often contrasting with the softer character of the associated RCC in which they arose [12].

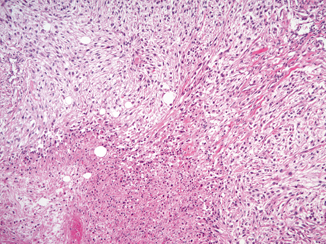

Microscopically, sarcomatoid differentiation is recognized as a malignant spindle cell component that resembles a sarcoma (Fig. 25.2). The appearance most commonly resembles fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, or an unclassified sarcoma. Heterologous differentiation is rare, often taking the form of osteosarcoma, chrondrosarcoma, or rhabdomyosarcoma, and has not been shown to affect outcome in the few instances reported [12, 14, 15].

Fig. 25.2

Sarcomatoid differentiation in a clear cell RCC. An area of sarcomatoid differentiation is seen as a malignant spindle cell proliferation that resembles a sarcoma. This example has associated tumor necrosis

Because sarcomatoid differentiation is associated with such aggressive behavior, its presence should be mentioned in the surgical pathology report. At the most recent meeting of the ISUP, there was consensus that no minimum amount of sarcomatoid differentiation was necessary to establish a diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma; thus, any amount of sarcomatoid differentiation should be mentioned in the surgical pathology report [11] .

Rhabdoid Differentiation

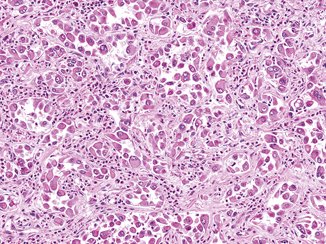

Rhabdoid differentiation, so named because it describes tumor cells that resemble rhabdomyoblasts, was described in RCC in a series by Gokden et al. in 2000 [17]. The rhabdoid phenotype is most commonly seen in association with clear cell RCC, but has been reported in numerous other subtypes, including papillary, chromophobe, medullary, and acquired cystic disease-associated RCC [18–22]. Cells with rhabdoid differentiation are variably cohesive and contain large, densely eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions and eccentrically located nuclei, often with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 25.3). These hyaline inclusions do not represent muscle differentiation but rather have been shown to be aggregates of cytoskeletal filaments or degraded organelles [17, 21].

Fig. 25.3

Rhabdoid differentiation in a clear cell RCC. Rhabdoid cells have large eccentric nuclei with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli as well as a densely eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion, causing the cells to resemble rhabdomyoblasts

Rhabdoid differentiation has been associated with increased tumor grade and stage, as well as frequent metastasis and death of disease in several studies [17, 21, 23]. More recently, it has been shown to be independently associated with poor outcome [24]. Therefore, it should be mentioned when present. This practice was likewise supported by ISUP consensus [11].

Additional Reporting Considerations

Evaluation of Nonneoplastic Parenchyma in Partial and Radical Nephrectomy Specimens

The second key concern after oncologic control that affects patients with RCC is postsurgical kidney function. This consideration, aided by improvements in surgical techniques over time, is the motivation for the use of nephron-sparing surgery. A significant number of patients (22.4 % of radical nephrectomy patients and 11.6 % of partial nephrectomy patients) without preoperative renal compromise can expect an increase in serum creatinine to greater than 2.0 mg/dL within 10 years of surgery due to surgical loss of nephrons [25]. This problem is compounded in patients with underlying kidney disease (as associated with diabetes mellitus or hypertension) [26].

The pathologist can provide useful information regarding likely future kidney function by sampling and assessing the nonneoplastic renal parenchyma present in a partial or radical nephrectomy specimen. Because mass effect from the tumor can cause local pathologic changes in the kidney parenchyma that are not indicative of global kidney dysfunction, sections for the evaluation of nonneoplastic disease should be taken as far from the tumor as possible. Thus, an evaluation for medical kidney disease is not recommended in partial nephrectomy specimens that contain less than 5 mm of surrounding nonneoplastic renal parenchyma [27].

The medical significance of evaluation of the nonneoplastic renal parenchyma in a nephrectomy specimen is underscored by the lethality of end-stage renal disease, even with dialysis, particularly in older patients. Average 60, 70, and 80-year-old end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis have life expectancies of 4.3, 3.1, and 2.2 years, respectively, indicating that many patients with both end stage renal disease and RCC will more likely die from their renal disease than from their tumors [27].

In a review of 246 nephrectomy specimens, Henriksen and colleagues identified diagnosable medical kidney disease in 24 (10 %) cases, which was not mentioned in 21 (88 %) of the surgical pathology reports. Diagnosable disease included diabetic nephropathy (19 cases, including 12 classifiable as severe diabetic nephropathy), thrombotic microangiopathy (three cases), sickle cell nephropathy (one case), and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (one case).

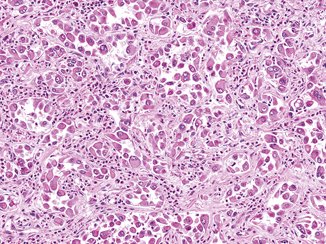

Fig. 25.4

A sample reporting template for renal tumors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree