Management of blunt abdominal trauma (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

•Historically useful for a rapid assessment of abdominal injury requiring surgery

•Has been replaced by focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), which is used in hemodynamically unstable patients to localize hemorrhage to a body cavity

•Sometimes used in developing countries where ready access to ultrasound technology or CT is not available

•Occasionally considered in hemodynamically unstable obese patients where FAST is technically challenging

•Procedure

•Make a small vertical midline incision down to the linea alba below the umbilicus

•In patients with pelvic fractures or hematoma, or women who are pregnant, make the incision above the umbilicus

•Insert a sterile Foley catheter aimed toward the pelvis and aspirate directly

•The presence of gross blood or any enteric contents at this point is an indication to abort the procedure and prepare the patient for a laparotomy

•Inject 10 cc/kg (up to 1 L) of warm crystalloid, wait for 5 to 10 minutes, and drain

•Drainage of at least 30% of the initial liter of fluid is necessary before sending the specimen for cell count

•Patient may need to be log-rolled or positioned in reverse Trendelenburg to allow adequate drainage

•Send fluid for cell count and amylase

•Any ONE of the following indicates a “positive DPL” mandating surgery:

•Gross blood on initial aspiration

•Enteric contents on initial aspiration

•100,000 red blood cells per cubic mm

•500 white blood cells per cubic mm

•Amylase >175

•Any bile or urine

A positive DPL is associated with no significant injury in up to 30% of patients; thus, it is not frequently used and is becoming replaced by other diagnostic modalities (FAST, CT in conjunction with physical exam).

A 28-year-old man presents to the emergency room following a bicycle crash. He is coherent but complains of abdominal pain. On presentation his blood pressure was 84/40 mmHg, which remained low at 95/50 mmHg following rapid infusion of 2 L of lactated Ringers through two large-bore IVs. What is the next step in management?

A chest X-ray (CXR) should be obtained to ensure appropriate triage of body cavities. Emergent laparotomy is indicated for any unstable patient with signs or symptoms of an abdominal source. At the time of operation, based on suspicion of the mechanism of injury, several maneuvers can be used to achieve exposure of critical organs. A CT scan should not be performed since the patient is unstable (given his episode of hypotension that did not resolve with IV fluid administration).

Exploring an Abdomen Full of Blood

•Pack all four quadrants

•Expose the diaphragmatic hiatus for supraceliac aortic clamping if necessary

•If there is a hematoma at the diaphragmatic hiatus making exposure of the aorta difficult, then access the aorta through a left thoracotomy

•Systematically remove the packs and define bleeding

•Use the Mattox maneuver to expose the supramesocolic aorta

•Use the Cattell maneuver to expose the inferior vena cava

•If the injury is localized to the infrarenal aorta, the supraceliac clamp can be moved down to the infrarenal position

Supraceliac Aortic Control

•Enter the lesser sac through the gastrohepatic ligament (beware of a replaced or accessory left hepatic artery)

•Retract the esophagus and stomach to the left, exposing the right crus

•Expose the supraceliac aorta by separating the two limbs of the right crus

•Clear medial and lateral walls bluntly (not circumferentially) and place the clamp on the aorta

Mattox Maneuver

•Provides access to the left retroperitoneum (aorta, left kidney, and ureter)

•Take down the left white line of Toldt and extend it up from the sigmoid colon to the splenic flexure

•Mobilize the spleen

•Reflect the viscera medially (to the right)

•This technique is also known as a lateral to medial visceral sweep

Cattell Maneuver

•Provides access to the right retroperitoneum (inferior vena cava, right kidney, and ureter)

•Incise the peritoneal reflection from the ileocecum to the hepatic flexure

Never perform a CT scan on an unstable patient.

A 43-year-old unrestrained driver of a motor vehicle crash arrives to the emergency department. He has a GCS of 5, pulse of 110, blood pressure at 120/94 mmHg, a large open fracture of the left lower extremity, and bruising over his chest and abdominal wall. What is the next step in management?

First, endotracheal intubation is indicated for airway protection. Next, perform a CXR and FAST to rule out hemorrhage in other compartments that can exacerbate hypotension and make intracranial pressure (ICP) worse. Then, correct his hypotension and hypoxemia before addressing the closed head injury, which will require an ICP monitor to titrate cerebral perfusion. It is critical to correct hypovolemia with adequate fluid replacement before giving mannitol or hypertonic saline (either can be used for elevated ICP).

Glasgow Coma Scale

•Used on all patients who present as traumas as an objective way of recording their level of consciousness

•Maximum score: 15

•Minimum score: 3

•(Scoring system table in Chapter 1)

Head Trauma

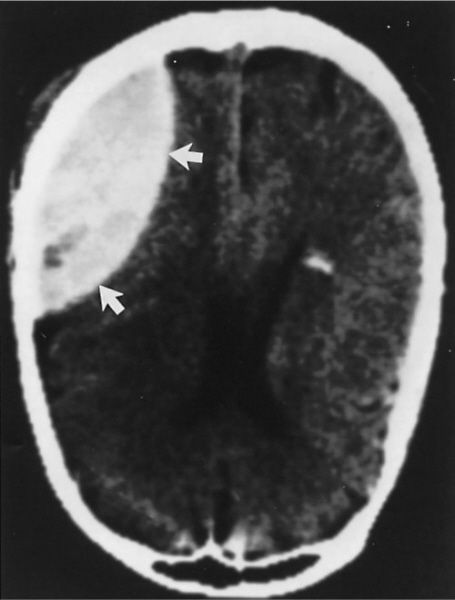

•Epidural hematoma

•Due to rupture of the middle meningeal artery

•Initial presentation: Initial brief loss of consciousness followed by a lucid interval

•Have a lens-shaped hematoma

•Treatment: Emergent craniotomy, evacuation of hematoma

CT of epidural hematoma. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

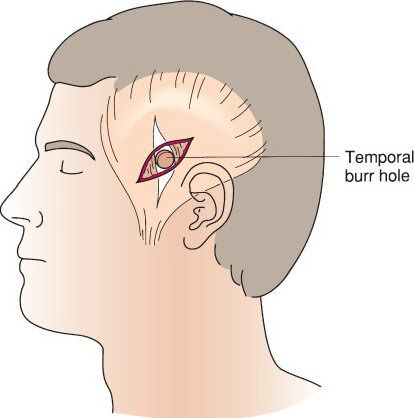

Location for the creation of a burr hole. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

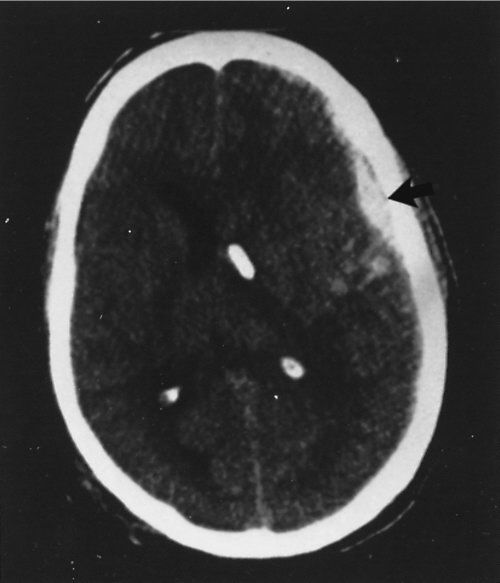

•Subdural hematoma

•Due to rupture of bridging veins between the dura and arachnoid

•Initial presentation: Either asymptomatic, or progressive lethargy, CN VI palsy depending on the size

•Have a crescent-shaped hematoma

•If patient does not have symptoms, they can be observed with serial neurologic exams and/or CT scans

•If patient is symptomatic, will need emergent craniotomy and decompression

Subdural hematoma. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)

•Trauma is the most common cause of an SAH

•Have blood in subarachnoid space (base of brain along cerebral gyri)

•Treatment: Keep ICP low and prevent secondary injury

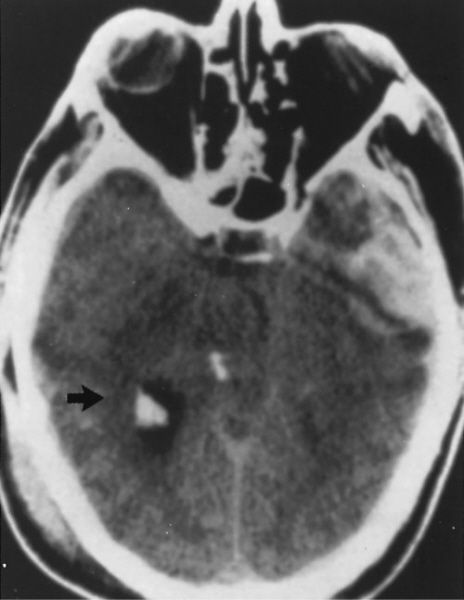

•Intraparenchymal hematoma

•Due to tearing of intraparenchymal capillaries

•Have parenchymal hematoma and may have mass effect

•Treatment: Observation or craniotomy if deteriorates

Contusion and associated intracerebral hematoma. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in trauma patients

•Give seizure prophylaxis for 1 week in this patients—typically 1 g Keppra BID

•Elevated ICP

•Goal ICP <20 mmHg

•Need to avoid hypotension to keep cerebral perfusion pressure >60

•Cerebral perfusion pressure = MAP – ICP

•

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree