Injury patterns in a car crash. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•If there is >1,500 mL of initial output or >200 mL/hour of output for the first 4 hours or >2,500 mL over the first 24 hours, the patient should have a thoracotomy

•In a hemodynamically stable patient, a chest X-ray should be obtained

•Physical examination by auscultation can be misleading in 20% to 30% of patients

Circulation

•All multi-trauma patients should have two large-bore IVs placed in the peripheral veins of the upper extremities

•Central venous lines are generally beneficial in unstable patients

•In patients with penetrating thoraco-abdominal injury, central venous access above and below the injury is preferred

•Alternatives include a saphenous vein cut-down at the ankle or groin

•An intraosseous infusion device can also be used for access, especially for small children and infants

•Patients who are hypotensive or in hemorrhagic shock should be resuscitated using 2 to 3 L of isotonic crystalloid solution as the initial volume challenge

•Patients who continue to be hemodynamically unstable following this challenge should be given uncrossmatched blood

•Two units of O+ blood are appropriate for males and women who are not of childbearing age, while O− should be used for women of childbearing age

•An appropriate response to fluid resuscitation is return of blood pressure and heart rate to normal

•Patients who continue to be in shock should undergo appropriate diagnostic evaluation emergently or be taken to the operating room for further resuscitation and control of bleeding

•If patient has distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds, and hypotension, i.e., Beck triad, they may have cardiac tamponade and need emergent pericardiocentesis or thoracotomy to evacuate the blood

•An echo will initially show impaired diastolic filling of the right atrium

•Note: Pericardiocentesis blood typically does not clot

•Patients who have sustained a spinal cord injury (especially above the first thoracic vertebrae) may present with a low blood pressure

•They are in “spinal shock”

•Systolic blood pressure is typically 80 to 90 mmHg with a normal heat rate or bradycardia

•Urine output is usually high

•Extremities are warm and well perfused (in hemorrhagic shock they are vasoconstricted with cool, mottled extremities)

•Vasopressors are sometimes used for peripheral vasoconstriction—should generally be reserved for cases where tissue perfusion is impaired. This is generally accomplished with the use of alpha agonists, such as phenylephrine.

•Other causes of shock (especially hemorrhage) may be present along with hypotension from spinal cord injury

Disability

•Neurologic examination

•Pupillary response

•Glasgow Coma Score

Exposure

•Multi-trauma patients should have all clothing removed for complete exposure

•Protect the entire spine until there is enough evidence to show that the spine is not injured

•The patient should be in a cervical collar and log-rolled to evaluate their back

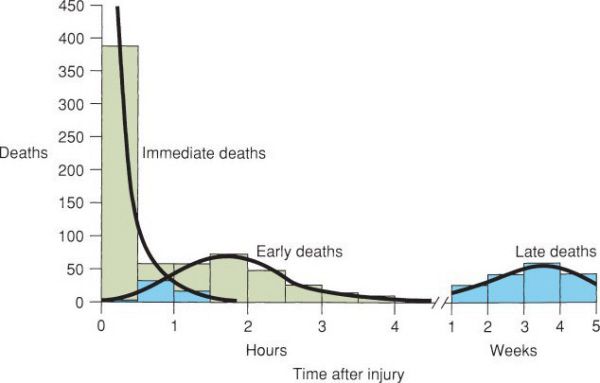

Three periods of peak mortality after injury. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

An unidentified male is dropped off at the ER door by a vehicle that then speeds away. He has sustained a gunshot wound to the right thigh just above the knee. His BP is 90 systolic and his HR is 130. He is conscious and complaining of pain. While he is being prepared for surgery, resuscitation for his hemorrhagic shock is initiated. Describe the early steps in fluid resuscitation.

Direct pressure applied to the external wound may be helpful. A tourniquet can be used in cases of overwhelming bleeding for short periods of time. Place two large bore IV catheters in the upper extremities. Rapidly infuse 2 to 3 L of isotonic crystalloid solution. If vital signs do not respond, start type O blood (O negative for females of child bearing age).

Blood Volume Resuscitation

•Control of bleeding via application of direct pressure to wounds, stabilization of fractures (splints, traction including the pelvis), etc.

•Pelvic stabilization can be achieved via external fixation devices including a binder or sheet passed around the pelvis and tied over the pubic symphysis to minimize pelvic expansion

•Tourniquets to control bleeding secondary to penetrating injury to the extremities are useful for the short term as a temporizing measure

•Blood loss should be replaced using the 3 to 1 rule: Replace blood loss with equal volumes of packed red blood cells and give three times the blood loss volume in crystalloid solution

•Example: A blood loss of 1,000 mL would require 1,000 mL of packed red blood cells (approximately 3 units) and 3,000 mL of lactated Ringer’s or normal saline solution

•While lactated Ringer’s solution is often the initial fluid of choice in trauma, saline is universally compatible with blood products and is preferred with concomitant transfusions

•Large volumes of normal saline solution will result in a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, which may confuse the end point of the resuscitation

•An elevated serum chloride will distinguish this condition from metabolic acidosis resulting from underperfusion of the tissues

Transfusion Guidelines for Fresh Frozen Plasma

•The major indication for fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is abnormal coagulation parameters

•FFP and platelet transfusion should be reserved for specific indications and should NOT be administered “prophylactically”

•Consider giving FFP with a congenital deficiency of AT-III, prothrombin, factors V, VII, IX, X, and XI, protein C, protein S, plasminogen, or antiplasmin

•FFP is indicated for bleeding due to an acquired deficiency from warfarin, vitamin K deficiency, liver disease, massive transfusion, or disseminated intravascular coagulation

The most common cause of diffuse “oozing” is hypothermia, underscoring the importance of keeping the patient warm.

Transfusion Guidelines for Platelets

•Transfuse for platelet count ≤10,000 platelets/mm3 (for prophylaxis)

•Transfuse for platelet count ≤50,000 platelets/mm3 for microvascular bleeding (“oozing”) or before a planned procedure

•Transfuse for demonstrated microvascular bleeding and a precipitous fall in platelets

•Transfuse patients in the operating room who have had complicated procedures or have required more than 10 units of blood AND have microvascular bleeding

•Transfuse patients with documented platelet dysfunction (e.g., prolonged bleeding time greater than 15 minutes, abnormal platelet function tests), petechiae, purpura, microvascular bleeding (“oozing”), or before an elective procedure

•Drawing on recent military experience, many centers are employing massive transfusion protocols for patients with acute, large volume blood loss

•Resuscitation with pRBCs and FFP in a ratio of 1:1 or 1:2 is frequently recommended

•Platelets are usually added in a ratio of 1:1 with ongoing severe bleeding

A 40-year-old man falls 35 m. Evaluation at the trauma center reveals three broken ribs on his left and a grade 3 splenic injury with fluid in the left upper quadrant of his abdomen. Nonoperative management is chosen and he is admitted to the surgical service. What should he be told regarding his prognosis?

Nonoperative management will be successful in most patients with blunt splenic injury, thus avoiding splenectomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree