3 Thrombosis, embolism and infarction

THROMBOSIS

CAUSES OF THROMBOSIS

Not all these factors need to be present at the same time; some will be dominant in one clinical situation, whilst others will predominate in another. For example, venous thrombosis is commonly due to alterations in blood flow, while arterial thrombosis is more commonly due to vessel wall changes of atheroma, which does not occur in veins.

Damage to the vessel wall

Arterial thrombosis

Atheroma of the arterial wall presents a good example of how vessel damage can lead to thrombosis and it is also a very common and important clinical situation. Atheroma is discussed in greater detail elsewhere (Chapter 9), but some points will be discussed here because they are relevant to the process of thrombosis.

Alterations in blood flow

The normal laminar flow may change to a turbulent pattern. This may happen with:

Alterations in the constituents of the blood

Alterations which may occur include:

Congenital thrombophilia

Acquired thrombophilia

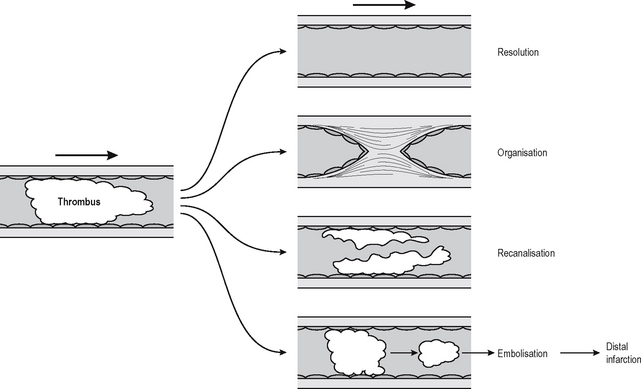

FATE OF THROMBI

It is not clear what factors determine which of these fates a thrombus will suffer, although size may be a factor. Small thrombi are being formed and resolved constantly, and some degree of disturbance of blood flow is probably required to tip the scales and cause a thrombus to organise. Certainly a larger thrombus will cause turbulence and/or inflammation and make it likely that further thrombosis will occur on its surface, causing the thrombus to lengthen, a process known as propagation. Resolution means that the clot is completely dissolved by processes of thrombolysis. In the clinical setting this is achieved by the use of thrombolytic enzymes, e.g. plasminogen activator or urokinase, but these have to be delivered onto the clot more or less directly, otherwise they diffuse through the blood stream and may become so dilute that they are ineffectual. Current therapies involve substances that act directly or indirectly on plasminogen activators. Compounds such as aspirin and heparin help prevent further thrombus formation but do not help in lysis of an established thrombus. If the thrombus is not completely removed then the residue undergoes organisation.

Organisation is the process by which the thrombus is converted to a scar and eventually covered by endothelial cells. Intravascular scarring is essentially similar to those processes involved in the production of scars from thrombi in wound healing generally (Chapter 1). The main difference between intravascular granulation tissue and a thrombus is that with a thrombus the vascular phase of granulation tissue is prolonged and, if the thrombus does not resolve completely, the capillaries fuse together, resulting in one or several new vessels passing through the scar. This process is called recanalisation and in some cases may result in one or more functional vascular channels.

EMBOLISM

An embolus is an abnormal mass of undissolved material which passes in the blood stream from one part of the circulation to another, impacting in vessels too small to allow it to pass. The actual material which passes along the blood stream is termed an embolus. When it impacts and obstructs the flow of blood, this is known as an embolism. Thus when a thrombus in the leg breaks off, this is an embolus, and when it impacts in the pulmonary artery it is a pulmonary embolism. Emboli may consist of:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree