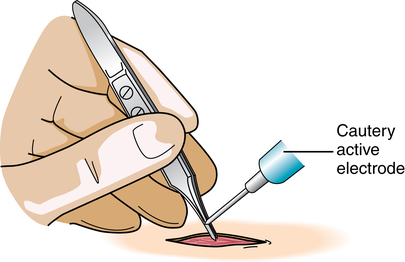

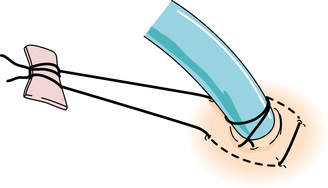

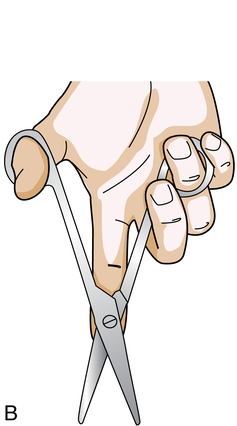

Chapter 5 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Identify key components of the first assistant’s knowledge and skill levels. • List pertinent perioperative activities of the first assistant. • Describe the patient care disciplines that with appropriate education function in the role of the first assistant. • Discuss the legal implications of the first assistant role. Knowledge of anatomic structures is critical to the first assistant. Tissue manipulation with instruments requires expert working knowledge of what is grossly seen and what is occluded from view. Improper retraction of tissue that has nervous and vascular structures contained within could cause complications such as neurologic dysfunction or vascular obstruction, resulting in thrombosis or embolization. Lack of this knowledge led to permanent damage to a child’s sciatic nerve as documented by Healthtrust v. Cantrell in Alabama.a In this lawsuit, the surgical technologist, who was performing in the role of surgical first assistant, was unable to identify the location of the sciatic nerve and caused serious injury with a retractor. The surgical technologist stated that he knew how to use retractors and held them where the surgeon placed them. This is an unacceptable and unsafe practice. The surgical first assistant must absolutely know all the ramifications of every action performed in the role and its effect on the patient’s outcome. The actions of the surgical first assistant should reflect the ability to identify all of the normal and abnormal structures in the surgical site and make intelligent, informed decisions about patient safety.1,4 Each first assistant is responsible for personal liability. There is no such thing as “working under someone else’s license” as commonly misinterpreted by some surgical staff members. For endoscopic procedures, the visual field is limited to the image on the video monitor.2 The first assistant needs a steady hand when using endoscopic instruments, because even the slightest motion can cause the entire surgical field to shift, placing the patient at risk for injury and causing nausea in team members who are viewing the video monitor. Extreme caution is exercised to prevent injury to tissue not in the direct visual field. The first assistant needs to know each step that will be encountered during the surgical procedure. It is important to anticipate and think in advance about each step to help the procedure move smoothly. The first assistant should have clear knowledge about not only the functional steps but also the indications for the procedure. Refer to Table 1-1 for the most common indications for a surgical procedure. The surgeon may request the first assistant to “buzz the forceps,” which means placing the active electrode against a forceps that is holding patient tissue and delivering electrical current after the tip is in complete contact with the instrument (Fig. 5-1). The gloved hand holding the forceps should have as much contact with the instrument as possible before the current is delivered. This decreases the amount of current passing over the holder’s hand and prevents concentration of electricity at a focal point on the hand. The current is delivered below the holder’s hand and as close to the actual patient tissue as possible to minimize the risk of alternate current pathway. The forceps is not permitted to touch any other part of the patient’s tissue or other instrumentation during this process or the patient will suffer burns to nontarget tissue. The first assistant commonly assists in closing the skin and applying dressings or supportive materials, such as casts. Improper technique of closure can lead to poor wound healing and unsightly scarring. Securing drains appropriately facilitates surgical site healing (Fig. 5-2). Keep in mind that the height of the OR bed should be adjusted to suit the reach of the tallest person at the sterile field. Shorter individuals should stand on steps or platforms for ergonomic comfort and adequate visualization of the surgical site. Sitting is only appropriate when the entire team is seated as to not change the level of the sterile field. Chapter 26 describes the processes for positioning, prepping, and draping the patient.

The surgical first assistant

First assistant’s knowledge and skill level

Surgical anatomy and physiology

Psychomotor dexterity

Procedure knowledge and techniques

Surgical site management

What does the first assistant do?

Position, prep, and drape the patient

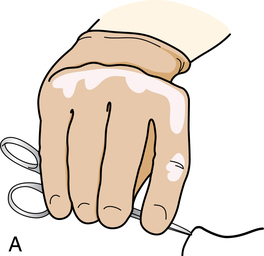

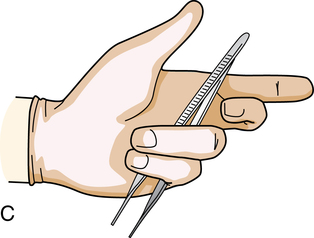

Handle instrumentation

The surgical first assistant

Website

Website