The rules of the game

Although the myofascial meridians are intended as a practical aid to working clinicians, ‘Anatomy Trains’ are most easily outlined as a game within this railway metaphor. There are a few simple rules, designed to direct our attention, among the galaxy of possible myofascial connections, toward those with common clinical significance (Fig. 2.1). Since the myofascial continuities described here are not exhaustive, the reader can use the rules given below to construct additional trains not explored in the body of this book. Those with serious structural anomalies – e.g. scoliotics or amputees – will create unique lines of myofascial transmission independent of the body’s common design.

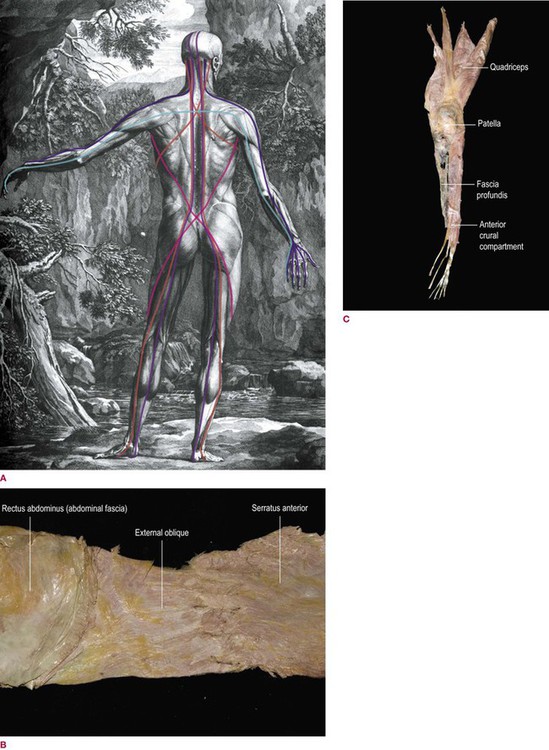

Fig. 2.1 (A) A back view summary of the Anatomy Trains myofascial meridians described in this book, laid over a figure from Albinus. (Reproduced with kind permission from Dover Publications, NY – see also Fig. In. 1.) (B) A dissection of an Anatomy Trains ‘station’. Notice how the zigzag attachments of both serratus and external oblique provide a station attachment to the periosteum of the ribs, but there is also a substantial fascial continuity between the two ‘tracks’. (C) The lower section of the Superficial Front Line, showing a dissection of the continuous biological fabric which joins the anterior compartment of the lower leg – toe extensors and tibialis anterior – through the bridle around the patella and into the quadriceps, spread here for easy viewing. Notice the inclusion of the fascia profundis (crural fascia) layer over the tibia. This is explained more fully in Chapter 4, but serves here to demonstrate the concept of the myofascial ‘track’. (DVD ref: Anatomy Trains Revealed) ![]()

1 ‘Tracks’ proceed in a consistent direction without interruption

A Direction

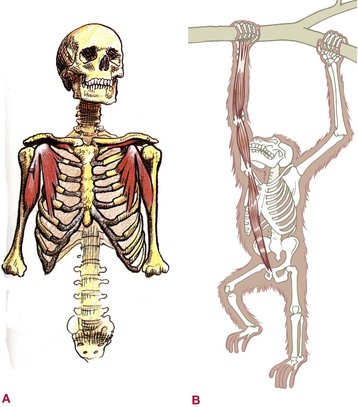

As an example, the pectoralis minor and the coracobrachialis are clearly connected fascially at the coracoid process (Fig. 2.2A, and see Ch. 7). This, however, cannot function as a myofascial continuity when the arm is relaxed by one’s side, because there is a radical change of direction between these two myofascial structures. (We will abandon this awkward term in favor of the less awkward ‘muscles’ if the reader will kindly remember that muscles are mere ground beef without their surrounding, investing, and attaching fasciae.) When the arm is aloft, flexed as in a tennis serve or when hanging from a chinning bar or a branch like the simian in Figure 2.2B, then these two line up with each other and do act in a chain that connects the ribs to the elbow (and beyond in both directions – the Deep Front Arm Line to the Superficial Front Line – thumb to pelvis).

Fig. 2.2 While the fascia connecting the muscles that attach to the coracoid process is always present (A), the connection only functions in our game of mechanical tensile linkage when the arm is above the horizontal (B). (A is reproduced with kind permission from Grundy 1982.)

On the other hand, fascial structures themselves can in certain cases carry a pulling force around corners. The peroneus brevis takes a sharp curve around the lateral malleolus, but no one would doubt that the myofascial continuity of action is maintained (Fig. 2.3). Such pulleys, when the fascia makes use of them, are certainly permitted by our rules.

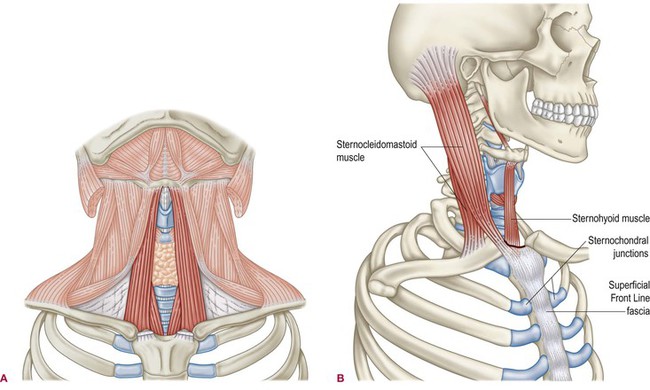

B Depth

Like abrupt changes of direction, abrupt changes of depth are also frowned upon. For example, when we look at the torso from the front, the logical connection in terms of direction from the rectus abdominis and the sternal fascia up the front of the ribs would clearly be the infrahyoid muscles running up the front of the throat (Fig. 2.4A). The error of making this ‘train’ becomes clear when we realize that the infrahyoid muscles attach to the posterior of the sternum, thus connecting them to a deeper ventral fascial plane within the rib cage (part of the Deep Front Line), not the superficial plane (Fig. 2.4B).

Fig. 2.4 Although a mechanical connection can be felt from chest to throat when the entire upper spine is hyperextended, there is no direct connection between the superficial chest fascia and the infrahyoid muscles because of the difference in depth of their respective fascial planes. The infrahyoids pass deep to the sternum, connecting them to the inner lining of the ribs and the intrathoracic fascia (A). The more superficial fascial planes connect the sternocleidomastoid to the fascia coming up the superficial side of the sternum and sternochondral junctions (B).

C Intervening planes

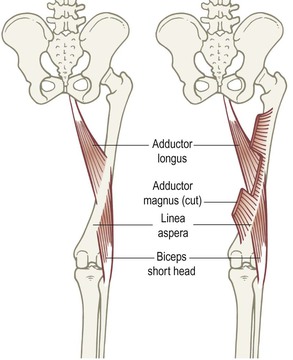

Resist the temptation to carry an Anatomy Train through an intervening plane of fascia that goes in another direction, for how could the tensile pull be communicated through such a wall? As an example, the adductor longus comes down to the linea aspera of the femur, and the short head of the biceps goes on from the linea aspera in the same direction. Surely that constitutes a myofascial continuity? In fact it does not, for there is the intervening plane of the adductor magnus, which would cut off any direct tensile communication between longus and biceps (Fig. 2.5). There may be some mechanical connection between these two through the bone, but myofascial force transmission is negated by the fascial wall between.

Fig. 2.5 If we just look at adductor longus and the short head of the biceps femoris (as on left), they appear to fulfill the requirements for a myofascial continuity. But when we see that the plane of adductor magnus intercedes between the two (as on the right) to attach to the linea aspera, we realize that such a connection cannot transmit force.