The Lateral Line

Overview

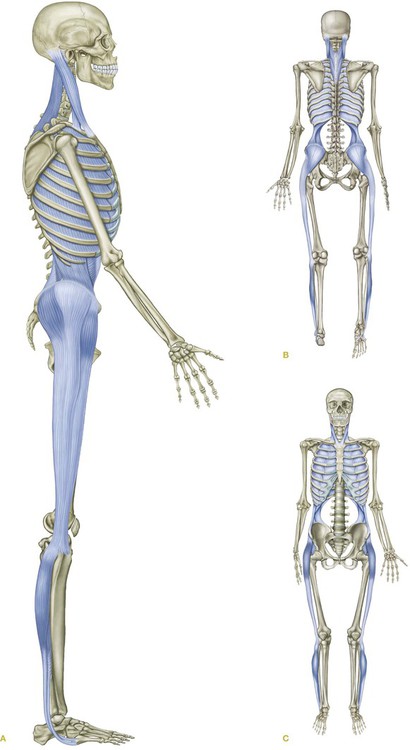

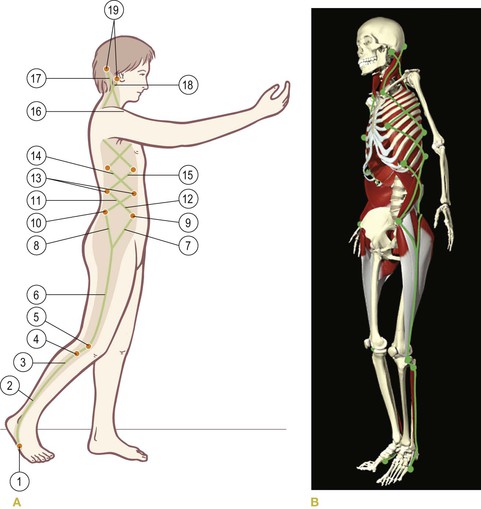

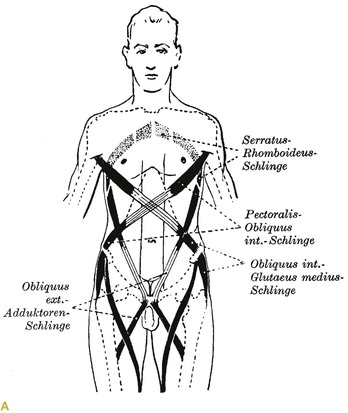

The Lateral Line (LL) (Fig. 5.1) brackets each side of the body from the medial and lateral mid-point of the foot around the outside of the ankle and up the lateral aspect of the leg and thigh, passing along the trunk in a ‘basket weave’ or crossed-shoelace pattern under the shoulder to the skull in the region of the ear (Fig. 5.2 A,B/Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

Lateral Line: myofascial ‘tracks’ and bony ‘stations’ (Fig. 5.2)

| Bony stations | Myofascial tracks | |

| Occipital ridge/mastoid process | 19 | |

| 17,18 | Splenius capitis/sternocleidomastoid | |

| 1st and 2nd ribs | 16 | |

| 14,15 | External and internal intercostals | |

| Ribs | 13 | |

| 11,12 | Lateral abdominal obliques | |

| Iliac crest, ASIS, PSIS | 9,10 | |

| 8 | Gluteus maximus | |

| 7 | Tensor fasciae latae | |

| 6 | Iliotibial tract/abductor muscles | |

| Lateral tibial condyle | 5 | |

| 4 | Anterior ligament of head of fibula | |

| Fibular head | 3 | |

| 2 | Fibulari muscles, lateral crural compartment | |

| 1st and 5th metatarsal bases | 1 |

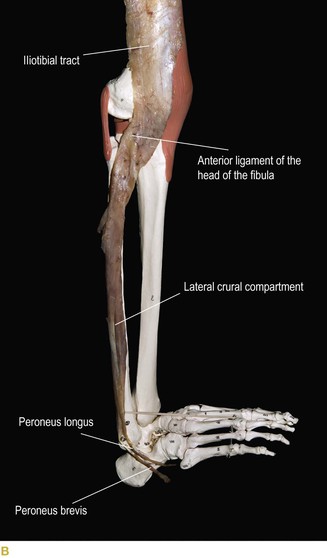

Fig. 5.2 (A) Lateral Line tracks and stations. The shaded area shows the area of superficial fascial influence. (B) Lateral Line tracks and stations using the Primal Pictures Anatomy Trains DVD-ROM, available from www.anatomytrains.com. (Image provided courtesy of Primal Pictures, www.primalpictures.com.)

Postural function

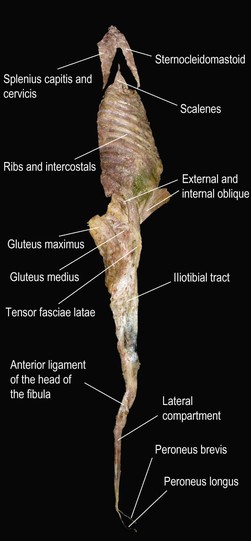

The LL functions posturally to balance front and back, and bilaterally to balance left and right (Fig. 5.3). The LL also mediates forces among the other superficial lines – the Superficial Front Line, the Superficial Back Line, all the Arm Lines, and the Spiral Line. The LL often acts to stabilize the trunk and legs in a coordinated manner to prevent buckling of the structure during activity.

Fig. 5.3 Here we see a dissection, taken from an embalmed cadaver, of the Lateral Line, including the fibularii (peroneals), connecting through tissues at the lateral knee to the iliotibial tract and abductors, which are fascially continuous with the lateral abdominal obliques. The ribs from the sternochondral junction in the front to the angle of the ribs posteriorly are included with their corresponding intercostal layers. The scalenes, attached to the upper two ribs, are included here, but the quadratus lumborum is not. The upper two muscles, the sternocleidomastoid and splenii looking like a chevron, do not attach to the rest of the specimen because they both attach inferiorly near or at the midline, whereas the specimen includes only about 30° each side from the coronal midline. (DVD ref: Anatomy Trains Revealed) ![]()

Movement function

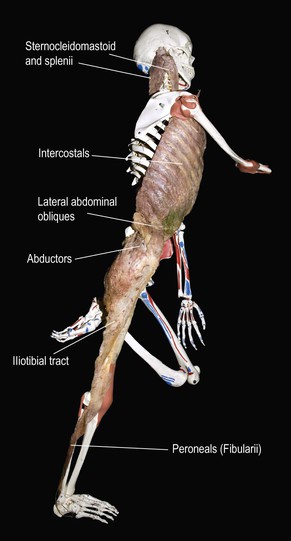

The LL participates in creating a lateral bend in the body – lateral flexion of the trunk, abduction at the hip, and eversion at the foot – but also functions as an adjustable ‘brake’ for lateral and rotational movements of the trunk (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.4 Here we see the same specimen laid into a classroom skeleton. The position is not quite accurate because the scapula was fixed and could not be moved or removed, but this photo nevertheless gives a sense of how the Lateral Line is used to stabilize coronal and rotational movements of the body during our predominantly sagittal motivation.

The Lateral Line in detail

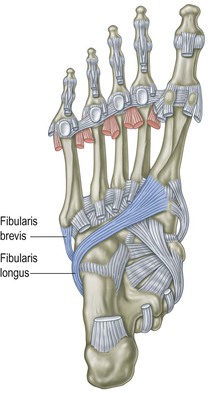

The LL manages to connect both the medial and the lateral side of the foot to the lateral side of the body. We begin – at the bottom again, simply as a convenience – with the joint between the 1st metatarsal and 1st cuneiform, about halfway down the foot on its medial side, with the insertion of the tendon of fibularis longus (Fig. 5.5). Following it, we travel laterally under the foot, and, via a channel in the cuboid bone, turn up toward the lateral aspect of the ankle.

Fig. 5.5 The Lateral Line begins in the middle of the medial and lateral arches of the foot, at the bases of the 1st and 5th metatarsals.

The LL picks up another connection, the fibularis brevis, about halfway down the lateral side of the foot. (The peroneal muscles were recently renamed as the ‘fibularis’ muscles; despite a lifetime of habit, we will follow the new convention.) From its insertion at the base of the 5th metatarsal, the fibularis brevis tendon passes up and back to the posterior side of the fibular malleolus, where the two fibulari muscles comprise the sole muscular components of the lateral compartment of the lower leg (see Fig. 2.3, p. 68). Thus both sides of the metatarsal complex are strongly tied to the fibula, providing support for the lateral longitudinal arch along the way (Fig. 5.6).

Fig. 5.6 The first track of the Lateral Line joins the metatarsal complex to the lateral side of the fibula, supporting the lateral longitudinal arch along the way.

General manual therapy considerations

Although both of the other ‘cardinal’ lines have both a right and a left side, the two Lateral Line myofascial meridians are sufficiently far from each other and from the midline to exert substantially more side-to-side leverage on the skeleton than either the SFL or the SBL, into both of which the Lateral Line blends at its edges (Fig. 5.2A). The LL is usually essential in mediating left side–right side imbalances, and these should be assessed and addressed early in a global treatment plan.

The lateral arch

![]() The lateral band of the plantar fascia was included in the Superficial Back Line (Ch. 3, p. 78). Although it is technically not part of the LL per se, it merits a mention as a factor in lateral balance. If the lateral muscles are so short as to evert the foot, or the foot is pronated in any case, the lateral band of the plantar fascia, running from the outer lower edge of the calcaneus straight forward to the 5th metatarsal base, will commend itself to work in the side-lying position, spreading the tissue between the two attachments (DVD ref: Lateral Line, 10:27–13:00)

The lateral band of the plantar fascia was included in the Superficial Back Line (Ch. 3, p. 78). Although it is technically not part of the LL per se, it merits a mention as a factor in lateral balance. If the lateral muscles are so short as to evert the foot, or the foot is pronated in any case, the lateral band of the plantar fascia, running from the outer lower edge of the calcaneus straight forward to the 5th metatarsal base, will commend itself to work in the side-lying position, spreading the tissue between the two attachments (DVD ref: Lateral Line, 10:27–13:00)![]() .

.

The fibulari (peroneals)

![]()

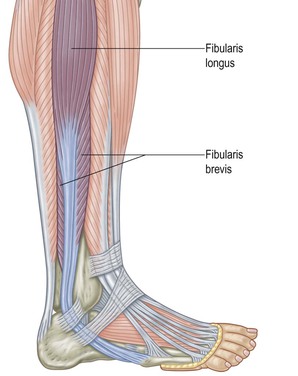

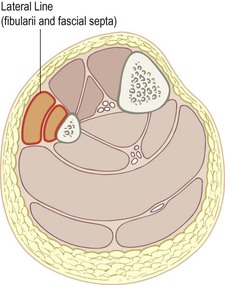

![]() The depth of the fibularis longus tendon on the underside of the foot and the brevity of the fibularis brevis make it impossible to accomplish anything useful with the LL below the malleolus, so we begin with the lateral crural compartment (Fig. 5.7). Fibularis longus and brevis blend together in this compartment, which is bounded by septa on either side. The anterior septum can be found on a line that runs roughly between the lateral malleolus and the front of the head of the fibula. The posterior septum, between the fibulari and the soleus, can be traced from just in front of the Achilles tendon up to just behind the fibular head. (See the palpation section below for more detail.) These septa and the overlying crural fascia are good places to open to address all forms of compartment syndrome.

The depth of the fibularis longus tendon on the underside of the foot and the brevity of the fibularis brevis make it impossible to accomplish anything useful with the LL below the malleolus, so we begin with the lateral crural compartment (Fig. 5.7). Fibularis longus and brevis blend together in this compartment, which is bounded by septa on either side. The anterior septum can be found on a line that runs roughly between the lateral malleolus and the front of the head of the fibula. The posterior septum, between the fibulari and the soleus, can be traced from just in front of the Achilles tendon up to just behind the fibular head. (See the palpation section below for more detail.) These septa and the overlying crural fascia are good places to open to address all forms of compartment syndrome.

Fig. 5.7 The lateral compartment consists of the deeper fibularis brevis and the overlying fibularis longus. This compartment is bound by septa on both anterior and posterior aspects, separating it from the anterior compartment (SFL) and the superficial posterior compartment (SBL) respectively.

The thigh

![]()

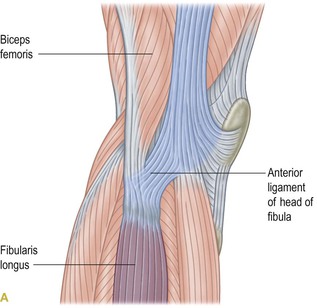

![]() Although the fibularis brevis originates on the lower half of the fibula, the longus (and thus the fascial compartment) and this train of the LL continue on up to the fibular head. The obvious, straight-ahead connection from this point is to continue on to the biceps femoris, and this myofascial meridian connection will be explored in the next chapter on the Spiral Line. The continuation of the LL, however, involves a different switch, going slightly anterior onto the anterior ligament of the head of the fibula onto the tibial condyle and blending into the broad sweep of the inferior fibers of the iliotibial tract (ITT) (Fig. 5.8A and B).

Although the fibularis brevis originates on the lower half of the fibula, the longus (and thus the fascial compartment) and this train of the LL continue on up to the fibular head. The obvious, straight-ahead connection from this point is to continue on to the biceps femoris, and this myofascial meridian connection will be explored in the next chapter on the Spiral Line. The continuation of the LL, however, involves a different switch, going slightly anterior onto the anterior ligament of the head of the fibula onto the tibial condyle and blending into the broad sweep of the inferior fibers of the iliotibial tract (ITT) (Fig. 5.8A and B).

Fig. 5.8 (A) The Lateral Line goes from the lateral compartment via the anterior ligament of the head of the fibula to the bottom of the iliotibial tract. (B) Tissues of the lower end of the iliotibial tract in fact have attachments to the tibia, the fibula, and the fascia of the lateral as well as the anterior crural compartment.

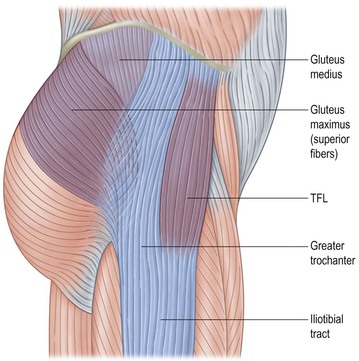

The ITT begins its upward journey here, starting from the lateral tibial condyle as a narrow, thick, and strong band that can be clearly felt on the lateral aspect of the lower thigh. Like the Achilles tendon, the ITT widens and thins as it passes superiorly. By the time it reaches the hip, it is wide enough to hold the greater trochanter of the femur in a fascial cup or sling (Fig. 5.9). The tension on the ITT sheet, which is maintained and augmented by the abductors from above and the vastus lateralis hydraulically amplifying from beneath, helps keep the ball of the hip in its socket when weight is placed on one leg. This arrangement also acts as a simple tensegrity structure. By acting as a ‘backstay’, some of the direct compressive stress of our body weight is taken off the femoral neck by the ITT, whose leverage can be augmented by a contraction of the underlying vastus lateralis.

Fig. 5.9 The second major track of the Lateral Line consists of the iliotibial tract and the associated abductor muscles, the tensor fasciae latae, the gluteus medius, and the superior fibers of the gluteus maximus.

The LL continues to widen above the trochanter, to include three muscular components: the tensor fasciae latae along the anterior edge, the superior fibers of the gluteus maximus along the posterior edge, and the gluteus medius, which attaches to the underside, the profound side, of the ITT’s fascial sheet (see Figs 5.3 and 5.4).

All these myofasciae tack down onto the outer rim of the iliac crest, stretching from the ASIS to the PSIS. This entire complex is used in the weighted leg in every step to keep the trunk from leaning toward the unweighted leg. In other words, the abductors are less often used to create abduction, but are used in every step to prevent hip adduction. This requires a stabilizing tension along the whole lower LL.

Derailment

![]() As we move from the appendicular portion to the axial portion of the LL, we face another derailment – a break with the general Anatomy Trains rules. The ITT – in fact, the whole lower LL – looks a bit like the letter ‘Y’ (Fig. 5.9). To follow the rules we would have to keep going up and out on the upper prongs of the ‘Y’ (as in Fig. 5.10A) with sheets or lines of myofasciae that continued to fan outward and upward from the ASIS and PSIS. We will find these continuations in the Spiral and Functional Lines (Chs 6 and 8). If, however, we look at how the myofascia arranges itself along the lateral aspect of the trunk from here on up, we find that the fascial planes cross back and forth in a basket weave arrangement (Figs 5.2 and 5.10B).

As we move from the appendicular portion to the axial portion of the LL, we face another derailment – a break with the general Anatomy Trains rules. The ITT – in fact, the whole lower LL – looks a bit like the letter ‘Y’ (Fig. 5.9). To follow the rules we would have to keep going up and out on the upper prongs of the ‘Y’ (as in Fig. 5.10A) with sheets or lines of myofasciae that continued to fan outward and upward from the ASIS and PSIS. We will find these continuations in the Spiral and Functional Lines (Chs 6 and 8). If, however, we look at how the myofascia arranges itself along the lateral aspect of the trunk from here on up, we find that the fascial planes cross back and forth in a basket weave arrangement (Figs 5.2 and 5.10B).

Fig. 5.10 Anatomy Trains rules would require that the ‘Y’ of the iliotibial tract continue out and around the body in spirals as in (A), but the actuality of the Lateral Line is that it starts a series of crisscrossing ‘X’s up the lateral aspect of the trunk, essentially like shoelaces sewing the front and back together via the sides (B). (Reproduced with kind permission from Benninghoff and Goerttler 1975.)

Although these sharp changes in direction break the letter of the Anatomy Trains rules, the overall effect of these series of ‘X’s (or diamonds, if you prefer) is to create a mesh or net which contains each side of the body as a whole – a bit like the old Chinese finger traps. The resultant structure is a wide net of a line that contains the lateral trunk from hip to ear (see Fig. 5.2).

The iliac crest and waist

![]() The upper edge of the iliac crest provides attachments for the latissimus dorsi and the three layers of the abdominal muscles. The outer two of these, the obliques, form part of the LL, and are fascially continuous with the ITT over the edge of the iliac crest (see Fig. 5.3)

The upper edge of the iliac crest provides attachments for the latissimus dorsi and the three layers of the abdominal muscles. The outer two of these, the obliques, form part of the LL, and are fascially continuous with the ITT over the edge of the iliac crest (see Fig. 5.3)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree