Chapter Four The anatomy of physics

CHECK YOUR EXISTING KNOWLEDGE

Now check your answers against those given at the end of the chapter.

The classification of joints

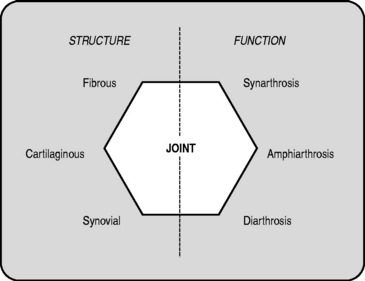

The first thing to realize is that there are, in effect, two ways in which you can organize joints: by their structure or by their function. Which way you chose largely depends on whether you are an anatomist (structuralist) or an orthopaedist (functionalist). As a student of manual medicine, you are, at various times, required to be either or both and therefore familiarity with both systems is required. Figure 4.1 summarizes these two different approaches.

In reality, there is considerable overlap between the two systems. In a fibrous joint, two adjacent bones are held tightly together by strong connective tissue. Obviously, such an arrangement does not allow for any significant movement so, functionally, this type of joint is termed a synarthrosis, from the Greek syn (together) and arthron (a joint). Therefore, as a rule, fibrous joints are synarthroses.

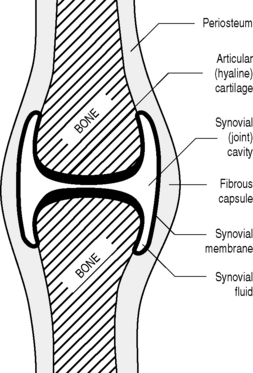

Finally, joints that have a synovial capsule (Fig. 4.2) have all the elements required for free movement, restricted only by the joint anatomy and the soft tissue holding elements. A joint that is freely moveable is referred to as a diarthrosis (Greek: dia, through; arthron, joint), although the amount of movement can vary considerably: take, for example, joints of the upper and lower limbs. In a quadrupedal animal, there is relatively little difference between the joints of the fore and hind limbs. In humans, although the template is the same, the joints of the lower extremity are much less flexible but able to bear the weight of the body; the joints of the upper limb allow a remarkable degree of dexterity, but at the expense of stability – try walking on your hands or writing with your toes!

Fibrous joints

The most consistent feature of fibrous joints is the absence of a joint space; any cavity between the two articulating bones tends to be filled with fibrous connective tissue. There are three types of fibrous joint found in the human body:

Sutures

Found between the bones of the skull, sutures show significant change throughout a lifetime. In infants, the bones of the skull do not make contact with each other and the dura mater, the outer lining of the brain, is directly palpable in the gaps between the bones. These gaps are called fontanelles. The most prominent of these is the anterior fontanelle (Fig. 4.3), bounded by the frontal and parietal bones. This fontanelle (the ‘soft spot’) has gone by the age of 24 months and, by the age of 6–7 years, the cranial sutures are, for the most part, united. From the third decade onwards, the fibrous interosseous tissue starts to ossify, forming an osseous union of the adjacent bones known as a synostosis (Greek: syn, together; osteon, bone).

True sutures

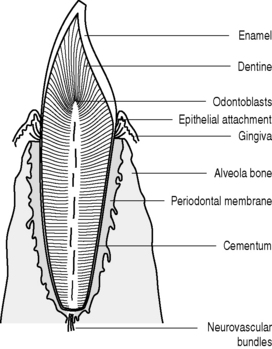

Peg and socket

The correct anatomical term for a peg and socket joint is a gomphosis (Greek: gomphos, a bolt). The only place in the human body where such joints are found is the insertion of the roots of the teeth into the sockets (alveoli) of the jaw (mandible and maxilla). The details of this arrangement are shown below (Fig. 4.4).

Syndesmosis

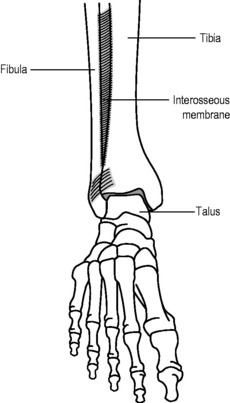

In this type of fibrous joint, two bones are united by a sheet of fibrous tissue. The term syndesmosis again has Greek origins: syn means together; desmos, a bond. It is at this point that the relationship between fibrous joints and synarthroses begins to break down. Some syndesmoses are aimed at giving rigidity: for example, the interosseous membrane between the tibia and fibula forms, in the ankle, part of the mortice into which the tenon of the talus fits (Fig. 4.5). If this were not solidly immobile, then it would be impossible to stand – the talus would simply separate the two bones above it and slide upwards towards the knee!

Figure 4.5 • Schematic diagram of the ankle joint: the interosseous membrane renders the distal talofibular joint a syndesmosis.

Cartilaginous joints

As suggested by the name, these joints are united by cartilage rather than by fibrous matter. As with fibrous joints, you will discover that there are several ways in which these joints can be classified; however, once you can understand the terminology, which system you decide to use then becomes a matter of informed choice.

Primary cartilaginous joints

These joints, mainly found in the immature skeleton, are also known as synchondroses (Greek: syn, together; khondros, cartilage). In order for a long bone to grow, the shaft of the bone (diaphysis from Greek: dia meaning through; phyesthai, to grow, therefore ‘to grow through’) and the end of the bone (epiphysis: as above but epi meaning upon, therefore ‘to grow upon’) are united by the epiphyseal growth plate, which allows an actively growing zone in which a cartilaginous template ossifies to allow bone expansion (Fig. 4.6). When full growth is achieved, the growth plate also ossifies, forming a synostosis and uniting the bone.

Secondary cartilaginous joints

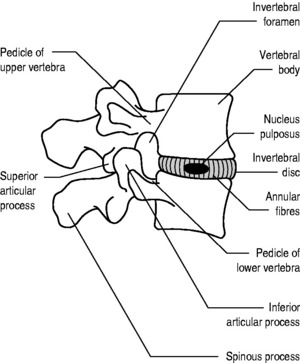

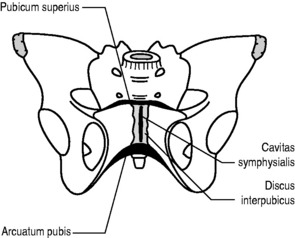

By contrast, secondary cartilaginous joints are amphiarthrotic, allowing a biomechanically significant amount of movement. In these joints, which are more commonly called sympheses (Greek syn, together; phyesthai, to grow), we also see, for the first time, the appearance of hyaline cartilage, lining the articular surfaces of bone. This cartilage can either be continuous, as it is in the joint between the sternum and manubrium, or it can be interrupted by articular discs, as is the case in the anterior intervertebral joints of the spine (Fig. 4.7) and the pubic symphysis (Fig. 4.8).

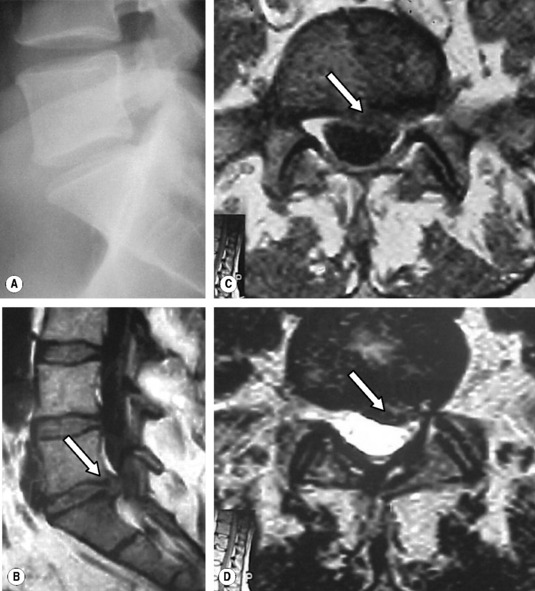

The commonest injury to a secondary cartilaginous joint – and one that is often treated by chiropractors, physiotherapists and osteopaths – is a ‘slipped disc’. In reality, the disc, which can be regarded as a nucleus of glycoproteins contained within concentric rings of fibrocartilage (called ‘annular fibres’ because of their resemblance to annular tree rings), slips nowhere. Rather, damage to the annular fibres (Grade I) can allow the nucleus to track outwards forming a bulge (Grade II) or herniating into the spinal column causing damage either to a single nerve root (Grade III, Fig. 4.9) or to the spinal cord and/or multiple nerve roots (Grade IV).

Synovial joints

The commonest joints in the body – and the ones, generally, of most interest to the manual physician – are the freely moveable (diarthrotic) synovial joints. The components that make up a synovial joint are detailed in Figure 4.2. As with cartilaginous joints, the bone of the articular surfaces is lined with a smooth coating of hyaline cartilage (except in the temporomandibular joint, the sternoclavicular and the acromioclavicular joint where the articular surfaces are covered with dense fibrous tissue instead). Here, however, the similarity stops.

The key feature of a synovial articulation is the joint space (in reality, more a potential than an actual space, particularly when weight bearing). Unlike the two classes of joints that we have previously examined, there is no connecting tissue between the two (or more) bones involved in a synovial joint. Instead, the joint is contained with a ligamentous capsule, the interior surface of which has cells that secrete synovial fluid, which acts to lubricate the joint’s surfaces and allows them to glide smoothly across each other. As a consequence, most synovial joints have considerably more movement than their fibrous and cartilaginous counterparts and are thus classified as diarthrodial. Their movement is restricted by the anatomical parameters of the joint, the supporting ligaments and the biomechanical limitations of the articulating muscles.

The major classification system for synovial joints is based on the anatomical relationship between the two articulating surfaces. This is useful for the clinician because, as we shall see later, there are rules of movement associated with these different types of joint that have clinical implications. Unfortunately, you will see a variety of terms used to describe each type of joint. In this text, the descriptive English terms will be used (as they are much easier to remember and actually tell you something about the joint – much as ‘peg and socket’ is a more useful term than ‘gomphosis’), although the variants that you may discover in other sources are also given. The classification of synovial joints, with examples of each type, is detailed below and summarized in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Classification of synovial joints

| Hinge | (Ginglymus) | Interphalangeal joints |

| Elbow (compound) | ||

| Plane | (Gliding) | Zygoapophyseal joints |

| Acromioclavicular (complex) | ||

| Pivot | (Trochoid) | Proximal radio-ulnar joint |

| Atlanto-odontoid joint | ||

| Ball & socket | (Spheroidal) | Hip |

| Shoulder (humeroscapular joint) | ||

| Saddle | (Sellaris) | 1st metacarpophalangeal joint |

| Sternoclavicular joint | ||

| Condyloid | (Ellipsoid) | Radiocarpal (compound) |

| 2nd – 5th metacarpophalangeal joints | ||

| Bicondylar | (Condylar) | Knee (complex, compound) |

| Temporomandibular (complex, compound) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

DICTIONARY DEFINITION

DICTIONARY DEFINITION

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

CLINICAL FOCUS

Fact File

Fact File