Chapter 23 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Calculate drug dosages in the perioperative environment. • List common drugs used in surgery. • Identify drug sources and the effect on patient use. Sealed glass tube containing a drug. Tip is scored for removal by snapping off. Drug is removed by a sterile syringe and filter needle to prevent aspiration of glass shards. One drug is used to alter or stop the effect of another drug. Standard scale of equivalents used to measure between metric, English, and apothecary. Used to perform a medical test or confirm a pathogenic condition. Colored solution used to identify structures with gross vision. Chemical used in solution to tint cellular structures for microscopic study. Radiopaque solution used during radiography or fluoroscopy to define structures on film or digital media. Liquid used to decrease the concentration of a substance. A nonsolid, nonliquid form of a chemical. Chemically equivalent drugs formulated as substitutes for brand-name products. Below the skin. Flow of a drug directly into the circulatory system. Drug that is taken in like a breath, and then absorbed through the respiratory tract. Insertion of a drug directly into the tissues using a syringe and needle. The first dose of a series given in a larger quantity than the subsequent doses. The physiologic response to a drug is in a select area of the body and not carried to other regions in an effective form.3 The actions and disposition of a chemical in the body. The drug is taken in by the cells of the body. The drug is evenly absorbed by the entire body. The drug is used throughout the body and broken down by major organs. The drug is released from the body in naturally excreted substances. An inert substance given to a patient to stimulate the power of suggestion of effectiveness. Commonly used as a control in experimental medicine. A term used to describe when a patient has multiple prescription medications from one or multiple prescribers. A synergistic action of one drug against another to cause an increased response by the body. Chemical or biologic preparation given with the intent of avoiding a disease state. The physiologic response of the body when exposed to a drug. The response can be positive or negative. Physiologic mechanisms are triggered by exposure to small doses of a given drug. Physiologic defense mechanisms are triggered by exposure to a drug or chemical, causing a potentially life-threatening response. Severe physiologic response to exposure to a drug or chemical, causing a definite threat to the patient’s life. Location in the body that acts in response to a chemical stimulus. Some drugs act by blocking a receptor site and prevent naturally produced chemicals from bonding. A secondary reaction that occurs in response to administration of a drug. The physiologic response to a drug is manifest in the entire body. The physiologic response caused by prolonged use of large quantities of a drug that makes average doses ineffective. A level of any given drug that causes a negative or possibly fatal physiologic response. A vacuum-sealed glass or plastic container of medication that is sealed by a rubber stopper. The drug is removed by a sterile syringe and needle. The main purpose of this chapter is to highlight information concerning the drugs specifically used in perioperative patient care. This chapter is not intended to be an all-inclusive pharmacologic resource. Drugs used in diagnostics, surgical procedures, anesthesia, and emergencies in the OR are described in more depth in the corresponding subsequent chapters. Drugs used in patient care areas other than the perioperative environment can be reviewed at www.globalrph.com/druglist.htm. This site has most of the common drugs and dosages listed in chart form. A No known risk during first trimester and no evidence in later trimesters B No risk shown in animals, but no studies on pregnant women C Possible risk found in studies in animals. No studies on pregnant women D Positive risk found in human fetus X Fetal anomalies found. Contraindicated for pregnant or possibly pregnant women • Phase I clinical trial: 20 to 80 healthy individuals for a period of 1 year. The drug is studied for safety in dosage, duration of action, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. • Phase II clinical trial: 100 to 300 people with actual disease process for which the drug is proposed treatment for a period of 2 years. The drug is studied for effectiveness and tolerability. Adverse reactions are monitored. • Phase III clinical trial: 1000 to 3000 patients in multiple health care settings participate. The drug is monitored to validate effectiveness and safety. • Phase VI postmarket surveillance: After the drug is on the market, the manufacturer monitors the users for therapeutic and nontherapeutic effects and reports to the FDA. 1. Find the product of the numbers. 2. Total the number of decimal places in the multiplicand and in the multiplier. 3. Mark off the total decimal places in the product, and insert a decimal. If the decimal must be moved farther than there are numbers, add a zero for each decimal place. To divide a decimal by a whole number: To divide a whole number or decimal by a decimal: 1. Move the decimal in the divisor to the right until the divisor is a whole number. 2. Move the decimal in the dividend to the right as many places as you moved the decimal in the divisor. 3. Place the decimal in the quotient directly above the (moved) decimal in the dividend. A fraction represents a part of a whole number. If a circle is divided into four equal parts, each part is ¼ of the circle, as seen in Figure 23-1. The numerator is 1 and the denominator is 4. The line between 1 and 4 means divide. Example: Reduce to lowest terms: 20/80 Both numbers are divisible evenly by 20: 20 × 20 × 1, and 80 × 20 × 4

Surgical pharmacology

Pharmacology baselines

Pregnancy classifications and lactation considerations

Drug development

Mathematics baselines

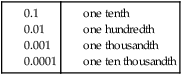

Decimals

Multiplication of decimals

Division of decimals.

Fractions

Reduce a fraction to lowest terms.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgical pharmacology

Website

Website