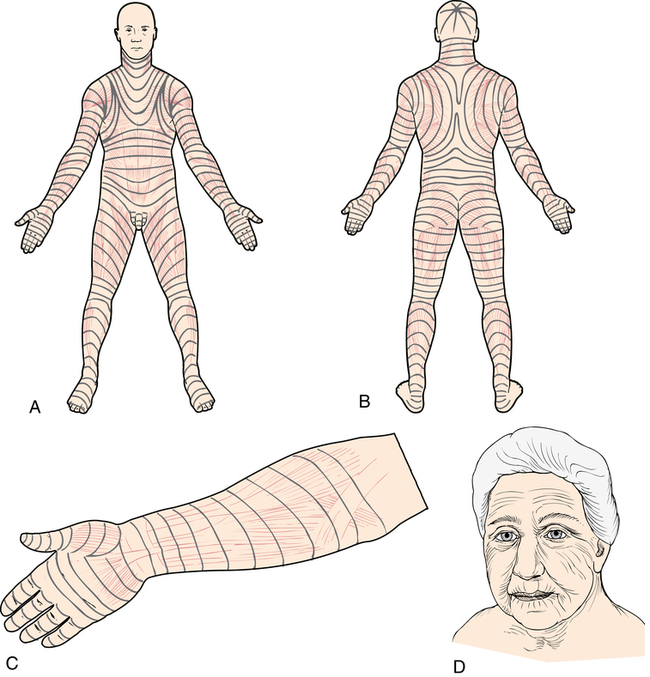

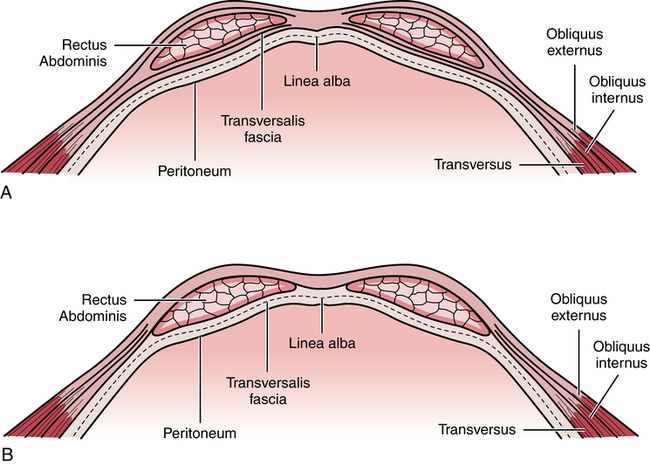

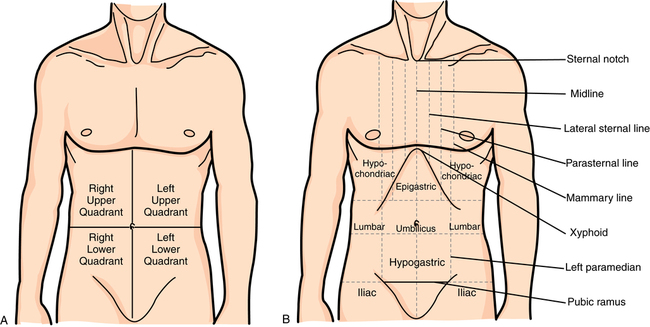

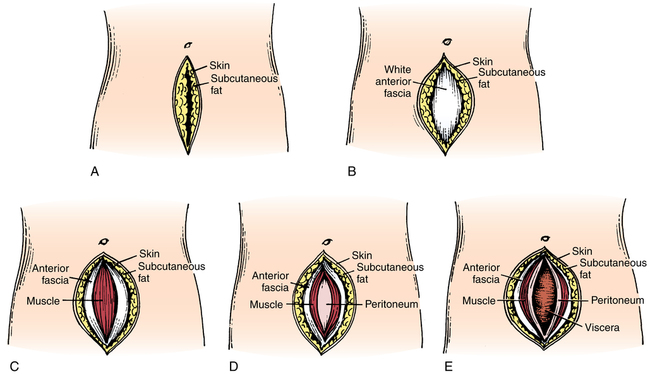

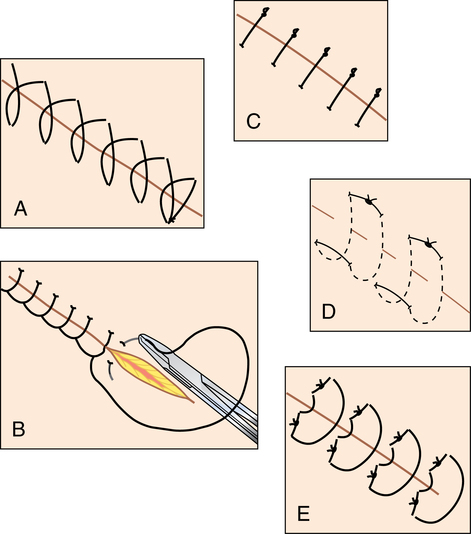

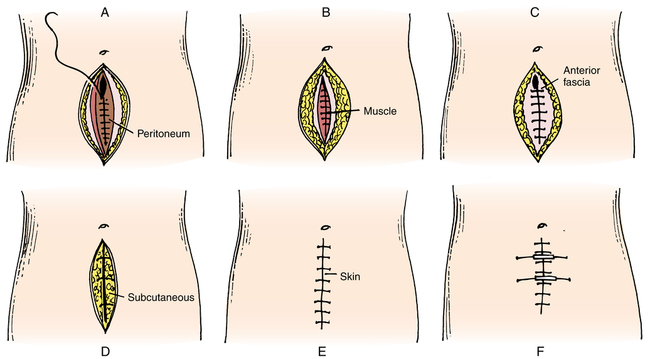

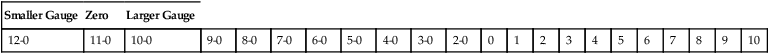

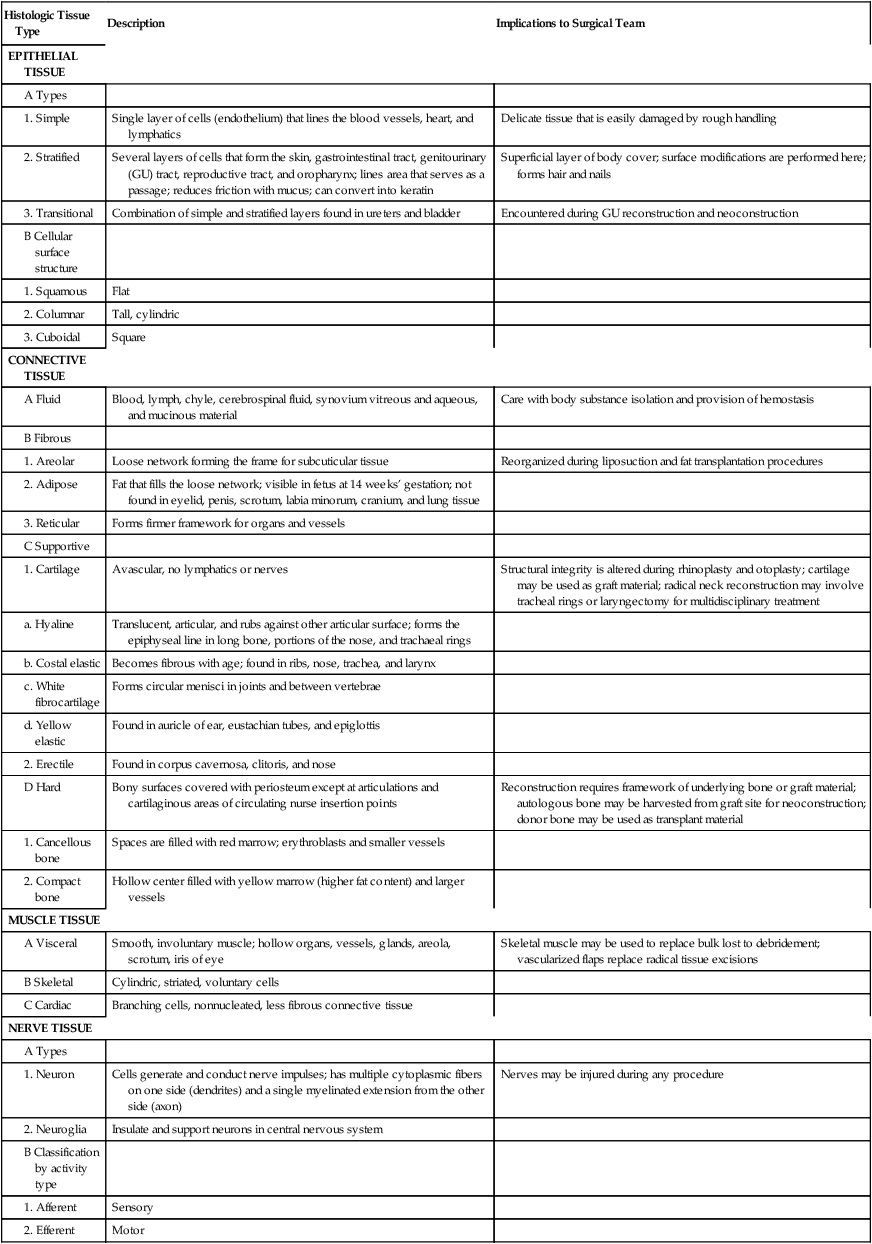

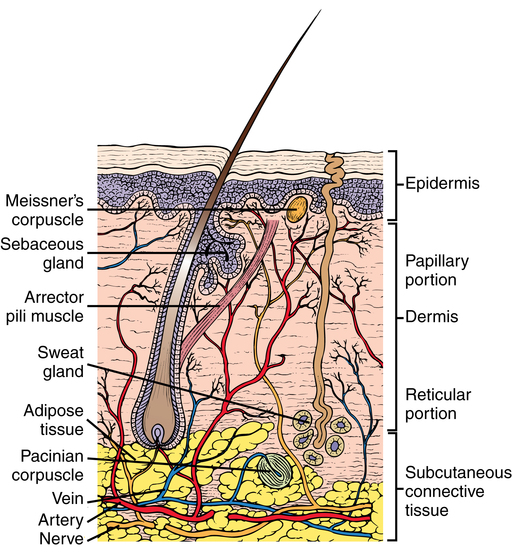

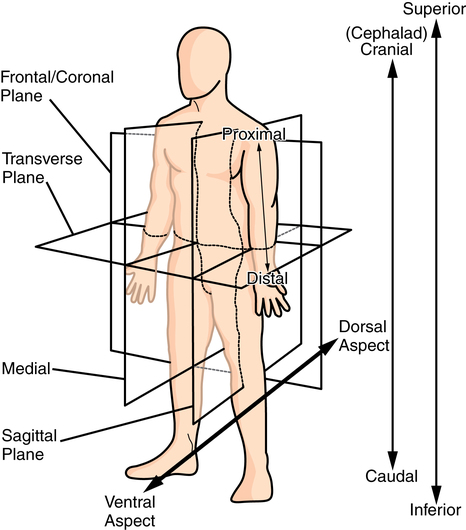

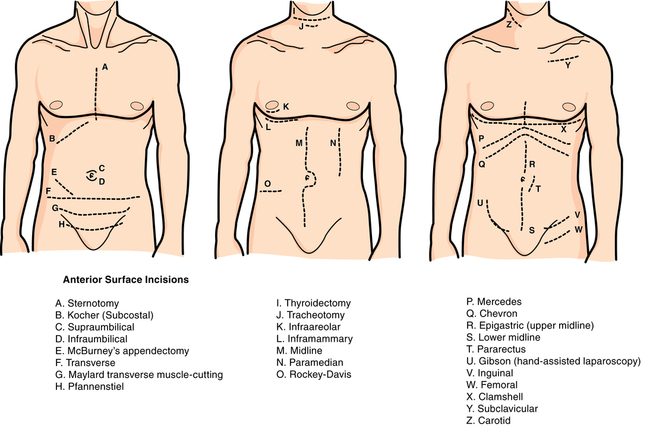

Chapter 28 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Describe the anatomy of the skin and underlying tissues. • Discuss the rationale for placement of the surgical incision. • Identify several surgical incisions and their associated surgical procedure. • Identify several absorbable sutures and their application. • Identify several nonabsorbable sutures and their application. • List several different types of needles and their application. Tissue structure and function vary according to location in the body. Basic tissue types are described in Table 28-1. TABLE 28-1 Four Basic Histologic Tissue Types From Fortunato NM, McCullough SM: Plastic and reconstructive surgery, St Louis, 1998, Mosby. The skin contributes to the health and well-being of the patient. Intact skin is an effective barrier to most harmful elements. Wounded, nonintact skin is an open avenue for microbial entry. Wounds occur intentionally or unintentionally. Most wounds, when treated properly, heal without incident. Unfavorable outcomes occur when wound healing is disrupted by poor circulation, infection, or immune dysfunction.7,9 Skin is a multifunction body cover, and skin assessment is an important measurement of generalized wellness. Skin color, texture, and condition can be the best predictors of how well a surgical site will heal. The most intricate procedure can be done in deep tissue layers, but the superficial layers are what the patient sees and measures the outcome against. Durability and viability of the skin of the perioperative patient are influenced by many factors. Within reasonable limits, in the absence of hemorrhage and sepsis, wound healing is predictable.10 Disregard for the principles of tissue handling and wound management can lead to complications. The intent of this chapter is to provide an overview of body tissues, surgical incisions, and surgical site closure. The skin is the largest and heaviest organ of the body. The two main layers that compose the integument are the epidermis and the dermis. The thickness of the skin and its layers is determined by its location. The combined thickness of the epidermis and dermis ranges from 4 mm on the back to 1.5 mm of scalp. Figure 28-1 shows a cross-section of the integument (skin) and its layers. Areas involving bone will incorporate vascularized periosteum over the bone. Natural lines of tension are formed by the relationship of the skin to the underlying musculature (Fig. 28-2). Austrian anatomist, Karl Langer (1819-1887) described how incisions could be more cosmetic if natural cleavage lines were followed when planning the surgical incision. The collagen fibers in the epidermis and dermis form an elliptical shape when the skin is incised in fusiform fashion along the natural lines. The angle of the incision should be no more than 30 degrees at each margin. The surgeon may undermine the tissue to minimize the distance between the skin edges. Closure is better when the edges meet during approximation. As the incision heals, tension of the skin is relaxed, causing minimal pulling and widening of the bridge of scar tissue. • Stratum corneum: Keratinized cells make up 75% of the epidermal thickness. Cells are shed from this level, which is referred to as the horny layer. It is thinner in hairy, thin-skinned areas. • Stratum lucidum: Cells are flattened. Organelles and nuclei are absent. • Stratum granulosum: This level is arranged in three to five layers. Mitotic activity creates cells for renewal of epidermal layers. • Stratum spinosum: This layer creates cells for renewal of epidermal layers. • Stratum basale: A single cell layer that lies between the junction of the epidermis and the dermis. Intense mitosis in this layer in combination with the basal layer and the spinosum causes epidermal regeneration. As cells are generated, they migrate upward, toward the surface. Melanocytes, located between basal cells and in hair follicles, create melanin, which causes skin pigmentation. Melanin enters and accumulates in keratocytes, causing superficial skin tone and providing ultraviolet protection. Exposure to sunlight causes darkening of existing melanin and accelerated generation of new melanin. The deep fascia is tough and less pliable. It runs the length of the muscle bundle and terminates in fibrous tendons that attach to bones beneath the periosteum. The anterior fascia of the abdomen is arranged in three layers that merge around the rectus abdominis muscles. The internal and external oblique muscles cover and surround the rectus muscles to the level of the linea circularis, or the landmark known as the arcuate line sometimes called the semicircular line of Douglas (Fig. 28-3). The arcuate line is formed by three fascial merges one third the distance between the umbilicus and the pubis. Below the level of the arcuate line the fascial layers are fully anterior with no posterior fascial component. The rectus abdominis is behind the layered fascia. The primary reference point for abdominal incisions is the umbilicus. Secondary surface landmarks include the xiphoid, the pubis, and the iliac crests. Incisions may be vertical, horizontal, or oblique and may occur in various areas of the torso (Fig. 28-4). Specialty incisions, such as those involving the head, limbs, breast, reconstructive procedures, and other organ systems are described in their respective chapters. The direction of the incisional line is determined by the anatomic plane in the body (Fig. 28-5). Some specialty instruments are constructed to dissect, debulk, or separate layers in a specific pattern according to the angle of the natural tissue arrangement. One example is a sagittal saw that is designed to cut bone along the sagittal plane. • Knowledge of previous surgery in the same region and the presence of adhesions • Ease and speed of entry into tissues • Size of the body habitus and the natural lines of tissue tension (Langer’s lines) • Maximum exposure of intended surgical site and adjacent structures (i.e, muscles, nerves, vessels, lymphatics) • Minimum trauma and scar formation • Least postoperative discomfort A laparotomy involves surgically opening the abdominal wall and entering the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 28-6). The skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised and the blood vessels are ligated or electrocoagulated. Both the posterior fascia and the peritoneum may be cut at the same time, thus exposing the contents of the abdominal cavity. Various types of incisions are used in a laparotomy, but each follows essentially the same technique. The incisions discussed in the following sections are applicable to open abdominal or pelvic procedures for specific organs or organ systems. The usual anterior surface incisions are depicted in Figure 28-7. Laparoscopy is performed through one puncture or multiple (usually one to five) incisions that are smaller (usually 5 to 10 mm), separate, and distinct. Endoscopy and laparoscopy are discussed in detail in Chapter 32. Closure of a surgical site or other wound is performed after necessary hemostasis has been achieved.6,7 Wounds include deep and superficial structures. Methods of wound closure include sutures, staples, clips, tapes, and glues. 1. Interrupted individual sutures are used for greater strength along the wound. Each stitch is taken and tied separately in a figure eight pattern for deeper tissues. If one knot slips, all the others hold. Halsted also believed that interrupted sutures were a barrier to infection, for he thought that if one area of a wound became infected, the microorganisms traveled along a continuous suture to infect the entire wound. 2. Sutures are as fine as is consistent with security. A suture stronger than the tissue it holds is not necessary. 3. Sutures are cut close to the knots. Long ends cause irritation and increase inflammation. Only external stitches have tails for ease of removal after healing. 4. A separate needle is used for each skin stitch. 5. Dead space in the wound is eliminated. Dead space is that space caused by separation of wound edges that have not been closely approximated by sutures. Serum or blood clots may collect in a dead space and prevent healing by keeping the cut edges of tissue separated. 6. Two fine sutures are used in situations usually requiring one large one. 7. Silk is not used in the presence of infection. The interstices (braid pattern) can harbor microorganisms. 8. Tension is not placed on tissue. Approximation versus strangulation preserves the blood supply. The strength of the wound is related to the condition of the tissue and the number of stitches in the edges. Care is taken not to place more sutures than necessary to approximate the edges.6,8 The amount of tissue incorporated into each stitch directly influences the rate of healing. The adequacy of the blood supply to the tissue needs to be preserved for healing to take place. The edges of the wound are intentionally directed by the placement of sutures during closure. Suturing techniques are depicted in Figure 28-8. Examples of suturing techniques that direct the wound edges for specific healing mechanisms include but are not limited to the following: 1. Everting sutures: These interrupted (individual stitches) or continuous (running stitch) sutures are used to evert skin edges. a. Simple continuous (running): This suture can be used to close multiple layers with one suture. The suture is not cut until the full length is incorporated into the tissue (see Fig. 28-8, A). b. Continuous running/locking (blanket stitch): A single suture is passed in and out of the tissue layers and looped through the free end before the needle is passed through the tissue for another stitch. Each new stitch locks the previous stitch in place (see Fig. 28-8, B). c. Simple interrupted: Each individual stitch is placed, tied, and cut in succession from one suture (see Fig. 28-8, C). d. Horizontal mattress: Stitches are placed parallel to wound edges. Each single bite takes the place of two interrupted stitches (see Fig. 28-8, D). e. Vertical mattress: This suture uses deep and superficial bites, with each stitch crossing the wound at right angles. It works well for deep wounds. Edges approximate well (see Fig. 28-8, E). 2. Inverting sutures: These sutures are commonly used for two-layer anastomosis of hollow internal organs, such as the bowel and stomach. Placing two layers prevents passing suture through the lumen of the organ and creating a path for infection. A single layer is placed for other structures, such as the trachea, bronchus, and ureter. The edges are turned in toward the lumen to prevent serosal and mucosal adhesions. The number of layers is proportional to the quality of the blood supply. Stitches can be interrupted or continuous. a. Halsted suture: A two-layer modification of the horizontal mattress suture used for friable tissue. b. Connell suture: A continuous single-layer suture of gut used for hemostasis in the inner layer of bowel with a separate outer inverting layer of alternating horizontal and vertical mattress sutures. c. Cushing suture: A continuous vertical mattress suture that unites one half of the lumen followed by a second continuous vertical mattress suture that completes the second half of the circumference. d. Grey-Turner suture: A series of inverted interrupted horizontal or vertical mattress stitches. e. Purse string suture: A continuous stitch that encircles and closes a lumen while inverting the edges. 1. Scissors should be stabilized by the index finger on the screw (tripod stance), the blades are angled slightly and slide down to the area just above the knot, and the suture is cut with the tips of the scissors. 2. The tips of the scissors must be visible to ensure that other structures are not injured by the cutting motion. 3. A hemostat and/or a second suture should be available in the event that the knot is inadvertently cut, releasing the sutured tissue. 4. A hemostat may be placed on one of the suture ends to stabilize the suture to be cut. 5. If removing a suture, a forceps is used to grasp the suture at the knot. Cut the suture between the knot and the skin. Extract the cut suture with the forceps. • Bridges are plastic devices placed on the skin to span the incision. The retention suture is brought through the skin on both sides of the incision and through holes on each side of the bridge and is fastened over the bridge. One type allows adjustment of tension on the edges of the incision during the postoperative healing period. • Bumpers are segments of plastic or rubber tubing. One end of the suture is threaded through the tubing before the suture is tied. It covers the entire retention suture strand that is on the skin surface to prevent irritation (Fig. 28-9, F). Compression bolsters are made from polyethylene foam held in place with malleable aluminum buttons to secure and distribute tension of retention sutures. • Buttons and beads are used as bolsters and bumpers to prevent the suture from retracting or cutting into skin or friable tissue. The suture is pulled through holes and tied over a button (e.g., with pull-out tendon sutures). Beads may be placed on the ends of pull-out subcuticular skin sutures. The devices are used most frequently in plastic and orthopedic surgery. • Umbilical tape: Aside from its original use for tying the umbilical cord on a newborn, umbilical tape may be used as a heavy tie or as a traction suture. It may be placed around a portion of bowel or a great vessel to retract it. These should be counted and accounted for at the end of the procedure. • Vessel loop: A length of flat silicone can be placed around a vessel, nerve, or other tubular structure for retraction. It can be tightened around a blood vessel for temporary vascular occlusion. These should be counted and accounted for at the end of the procedure. • Aneurysm needle: An aneurysm needle is an instrument with a blunt needle on the end for passing suture. The eye is on the distal end of the needle. The needle forms a right or oblique angle to the handle, which is one continuous unit with the needle. The needles are made in symmetric pairs, right and left. The surgeon uses them to place a ligature around a deep, large vessel, such as in a thyroidectomy or in thoracic surgery. They can be used to pass a suture tape around an incompetent cervix to perform cerclage. These should be counted and accounted for at the end of the procedure. (Refer to Figure 34-16 in Chapter 34.) • Extracorporeal method: The swaged needle and both ends of the suture are brought outside the body through the trocar. The needle is cut off, and the knot is loosely fashioned. The knot is reintroduced into the body through the trocar by means of a knot-sliding cannula. It is snugged into position and tightened against the tissue. The ends of the suture are cut close to the knot with endoscopic scissors. Excess suture ends are removed through the endoscope. • Intracorporeal method: The needle and suture are passed through the tissue with an endoscopic needle holder. Endoscopic instruments are used to tie the knot and cut the suture inside the body. • It must be sterile when placed in tissue. Sterile techniques must be rigidly followed in handling suture material. For example, if the end of a strand drops over the side of any sterile surface, discard the strand. Almost all postoperative wound infections are initiated along or adjacent to suture lines. Affinity for bacterial contamination varies with the physical characteristics of the material. • It must be predictably uniform in tensile strength by size and material. Tensile strength is the measured pounds of tension or pull that a strand will withstand before it breaks when knotted. Minimum knot-pull strengths are specified for each basic raw material and for each size of that material by the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP). Tensile strength decreases as the diameter of the strand decreases. • It must be as small in diameter as is safe to use on each type of tissue. The strength of the suture usually needs to be no greater than the strength of the tissue on which it is used. Smaller sizes are less traumatic during placement in tissue and leave less suture mass to cause tissue reaction. The surgeon ties small-diameter sutures more gently and thus is less apt to strangulate tissue. A small-diameter suture is flexible, easy to manipulate, and leaves minimal scar on skin. • USP-determined sizes range from heavy 10 (largest) to very fine 12-0 (smallest); ranges vary with materials. Taking size 1 as a starting point, sizes increase with each number above 1 and decrease with each 0 (zero) added. The more 0s in the number, the smaller the size of the strand. As the number of 0s increases, the size of the strand decreases. In addition to this system of size designation, the manufacturer’s labels on boxes and packets may include metric measures for suture diameters. These metric equivalents vary slightly by types of materials. Box 28-1 shows how suture gauge is measured on a scale in numeric descriptions from smallest to largest. • It must have knot security, remain tied, and give support to tissue during the healing process. However, sutures in the skin are always removed 3 to 10 days postoperatively, depending on the site of incision and cosmetic result desired. Because they are exposed to the external environment, skin sutures can be a source of microbial contamination of the wound that inhibits healing by first intention. • It must cause as little foreign body tissue reaction as possible. All suture materials are foreign bodies, but some are more inert (less reactive) than others.

Surgical incisions, implants, and wound closure

The surgical incision

Anatomy and physiology of the integument

Histologic Tissue Type

Description

Implications to Surgical Team

EPITHELIAL TISSUE

Single layer of cells (endothelium) that lines the blood vessels, heart, and lymphatics

Delicate tissue that is easily damaged by rough handling

Several layers of cells that form the skin, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary (GU) tract, reproductive tract, and oropharynx; lines area that serves as a passage; reduces friction with mucus; can convert into keratin

Superficial layer of body cover; surface modifications are performed here; forms hair and nails

Combination of simple and stratified layers found in ureters and bladder

Encountered during GU reconstruction and neoconstruction

Flat

Tall, cylindric

Square

CONNECTIVE TISSUE

Blood, lymph, chyle, cerebrospinal fluid, synovium vitreous and aqueous, and mucinous material

Care with body substance isolation and provision of hemostasis

Loose network forming the frame for subcuticular tissue

Reorganized during liposuction and fat transplantation procedures

Fat that fills the loose network; visible in fetus at 14 weeks’ gestation; not found in eyelid, penis, scrotum, labia minorum, cranium, and lung tissue

Forms firmer framework for organs and vessels

Avascular, no lymphatics or nerves

Structural integrity is altered during rhinoplasty and otoplasty; cartilage may be used as graft material; radical neck reconstruction may involve tracheal rings or laryngectomy for multidisciplinary treatment

Translucent, articular, and rubs against other articular surface; forms the epiphyseal line in long bone, portions of the nose, and trachaeal rings

Becomes fibrous with age; found in ribs, nose, trachea, and larynx

Forms circular menisci in joints and between vertebrae

Found in auricle of ear, eustachian tubes, and epiglottis

Found in corpus cavernosa, clitoris, and nose

Bony surfaces covered with periosteum except at articulations and cartilaginous areas of circulating nurse insertion points

Reconstruction requires framework of underlying bone or graft material; autologous bone may be harvested from graft site for neoconstruction; donor bone may be used as transplant material

Spaces are filled with red marrow; erythroblasts and smaller vessels

Hollow center filled with yellow marrow (higher fat content) and larger vessels

MUSCLE TISSUE

Smooth, involuntary muscle; hollow organs, vessels, glands, areola, scrotum, iris of eye

Skeletal muscle may be used to replace bulk lost to debridement; vascularized flaps replace radical tissue excisions

Cylindric, striated, voluntary cells

Branching cells, nonnucleated, less fibrous connective tissue

NERVE TISSUE

Cells generate and conduct nerve impulses; has multiple cytoplasmic fibers on one side (dendrites) and a single myelinated extension from the other side (axon)

Nerves may be injured during any procedure

Insulate and support neurons in central nervous system

Sensory

Motor

Langer’s lines

Epidermis

Tissue layers under the integument

Fascia.

Surgical landmarks

Placement of the surgical incision

Abdominal surgery

Types of abdominal incisions

Wound closure

Suture basics

Suturing techniques

Halsted suture technique.

Principles of suturing

Methods of suturing.

Cutting sutures.

Retention bridges, bolsters, and bumpers.

Traction suture.

Endoscopic suturing.

Specifications for suture material

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgical incisions, implants, and wound closure

Website

Website