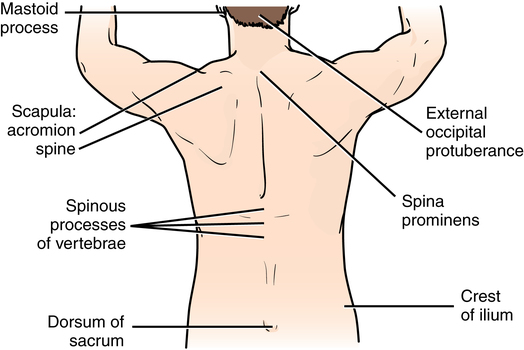

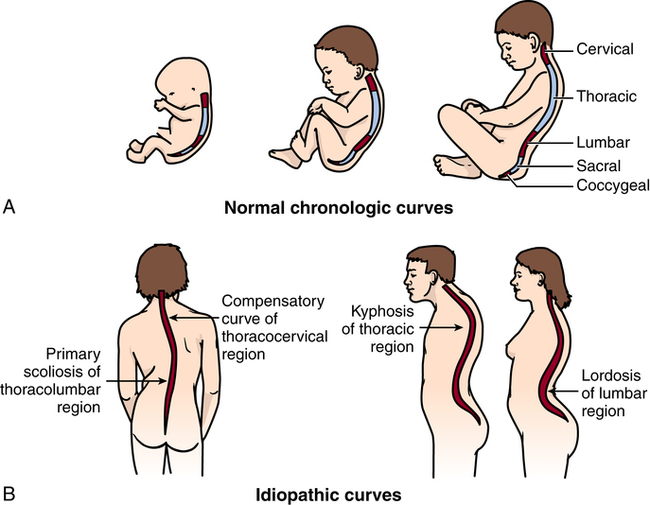

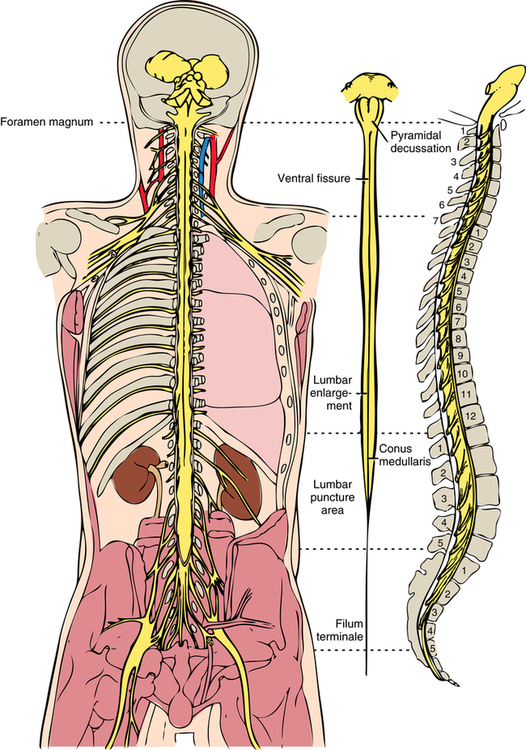

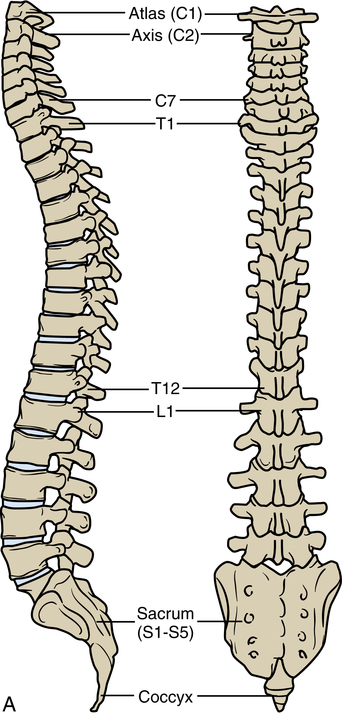

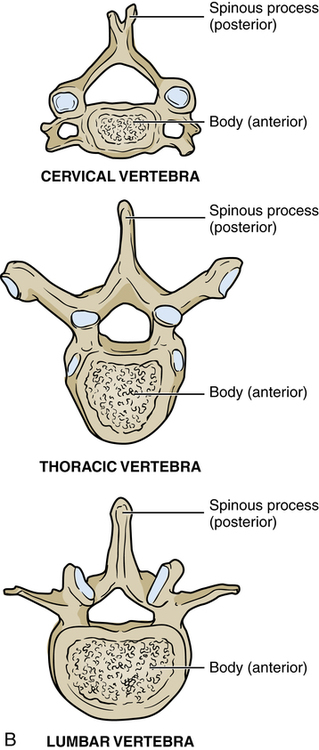

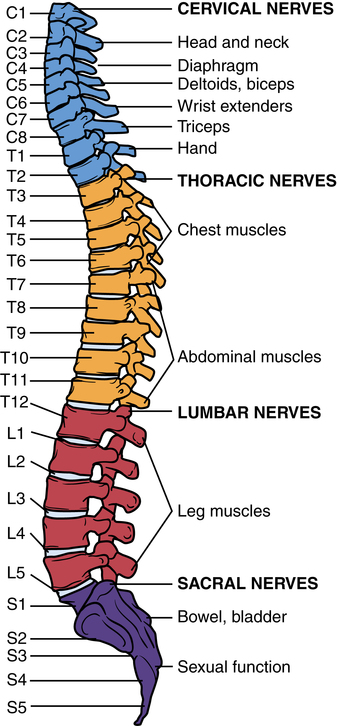

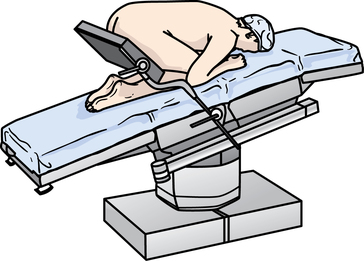

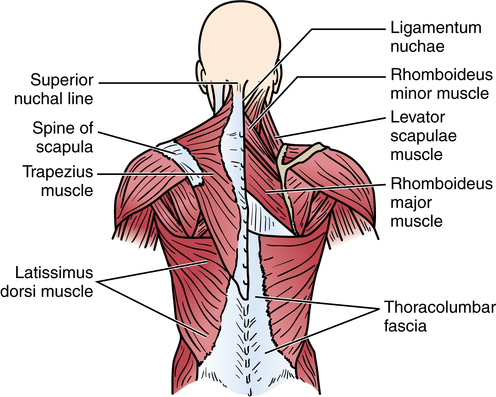

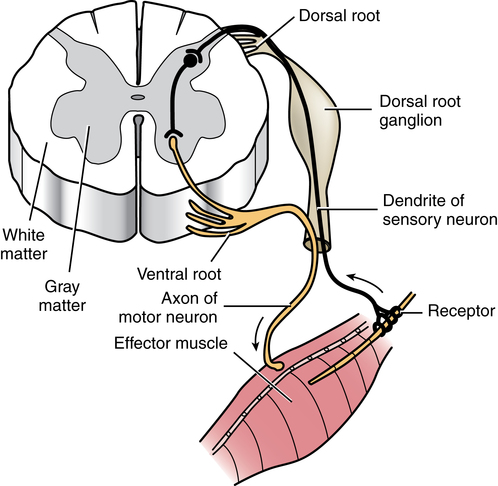

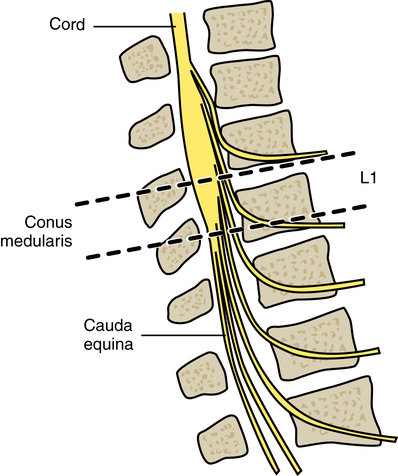

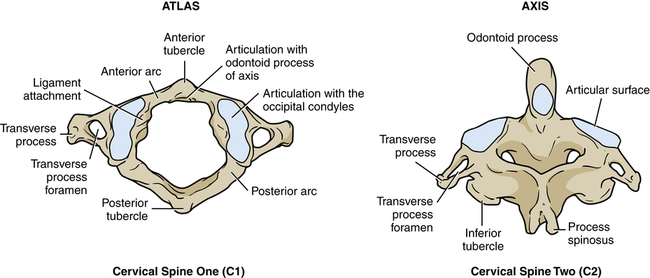

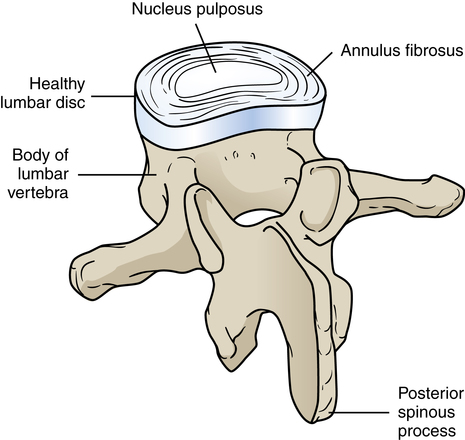

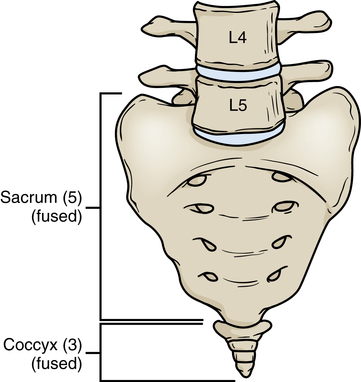

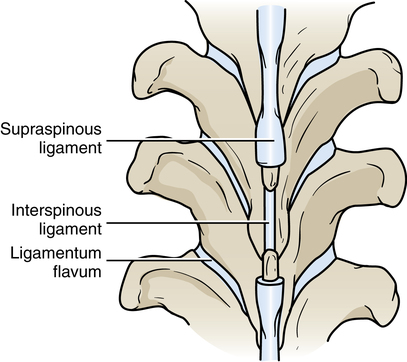

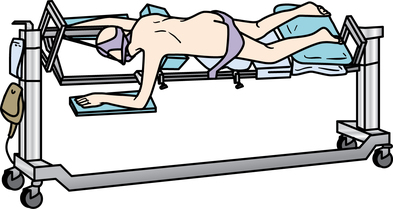

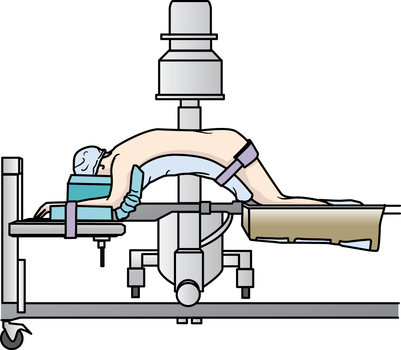

Chapter 38 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Describe the anatomy of the vertebral column and spinal cord. • Describe the implications of dermatome and myotome distributions. • Discuss the implications of an individualized plan of care for each type of spinal surgery. • Differentiate between the types of spinal positioning devices and OR beds. • Compare the salient points of spinal surgery that apply to orthopedic and neurologic procedures. The vertebral column and spinal cord comprise the posterior aspect of the trunk of the body. The relationship between the bones and nerves is evaluated first from a topographic perspective with assessment of the alignment of specific external landmarks (Fig. 38-1). The external dorsal musculature frames the margins of the surgical landmarks used in planning the posterior incision for spinal surgery (Fig. 38-2). The configuration of the spinal curvature is dependent on chronologic and idiopathic factors. Each age group, as shown in Figure 38-3,A, displays a different set of normal spinal curves based on physiologic development. Abnormal curvatures can be age related but sometimes idiopathic without consideration for age (Fig. 38-3, B). The spinal cord is between 17 and 20 inches (43 to 50 cm) long and passes through a central canal in the vertebral column to the level of the second or third lumbar vertebra (Fig. 38-4). Pairs of spinal nerve roots branch off to each side of the body from 31 segments of the spinal cord as it passes through the vertebrae. The spinal nerves are as follows: The spinal nerves carry sensory and motor impulses between the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The cord is composed of gray matter (cell bodies) on the inside and white matter (nerve fibers) on the outside. This is the exact opposite of the substance of the brain. The ventral nerve roots are the motor axons to the muscles and glands, and the dorsal nerve roots are the sensory dendrites (Fig. 38-5). The dorsal root ganglion is easily entrapped by the bony vertebrae and causes pain and disability. The cephalad portion of the cord begins at the base of the brain at the foramen magnum. The caudal portion of the spinal cord thickens and ends at L1 to form the conus medullaris before terminating in a fibrous tail known as the cauda equina (horse’s tail; Fig. 38-6). The nerve fibers that extend beyond L2 to L3 form the lumbosacral plexus. • A thick cylindric body that bears a portion of the weight of the torso. • Two posterolateral extensions that form the proximal bony vertebral (neural) arch. These extensions form thick pedicles that connect to flatten laminae posteriorly. The laminae connect at the spinous process, forming a circle. Each pedicle has a notch superiorly and inferiorly to seat the vertebrae above and below. • A transverse wing-shaped spinous process that is formed by the connection of the posterior laminae. The central foramen shapes the spinal canal. The bony structure of the vertebral column extends from the foramen magnum at the base of the skull to the coccyx (Fig. 38-7, A). The 33 vertebrae, which provide support for the body, vary in size and shape according to location and are separated by flexible discs over the anterior surface of the body (Fig. 38-7, B). Each disc is composed of two parts: an exterior annulus fibrosus and an interior gel referred to as the nucleus pulposus. The seven cervical vertebrae are in the neck and form the secondary curvature. They are lighter weight with a smaller disc-bearing body. The top two cervical vertebrae, C1 atlas and C2 axis, have clearly distinct landmarks. The atlas laminae form a circle around the odontoid process of the axis so the head has a wide range of circular and linear motion (Fig. 38-8). The atlas-axis complex has no disc or spinous process and is considered to be the strongest vertebrae of the cervical portion of the vertebral column. The five lumbar vertebrae are posterior to the retroperitoneal cavity and are designed to carry the heaviest load of the entire vertebral column with the least amount of flexibility. The body and disc of each lumbar vertebra are thick and form a secondary curvature. Figure 38-9 illustrates the combined lumbar vertebra-disc unit. The five sacral vertebrae are fused in the adult to form the sacrum, and the four fused coccygeal vertebrae form the coccyx (Fig. 38-10). Collectively, these two sets of fused vertebrae form the posterior aspect of the pelvic girdle. Each vertebra is connected to the other by a series of ligamentous fibers (Fig. 38-11). The vertebral column measures about 28 inches (71 cm) in the average-size adult. The physiologic relationship between the spinal cord, spinal nerves, and bony vertebral column affects multiple body systems if the curvature is misaligned or some pathology changes the size of a foramen or joint. Figure 38-12 illustrates the major organ systems and the corresponding spinal nerves that can cause problems with physiologic functioning. For diagnosis of spinal conditions, computed tomography (CT) is used to detect abnormal bone. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to evaluate spinal injuries. MRI and myelography outline soft tissue abnormalities, such as disc degeneration, protrusion, or rupture.13 Because it is noninvasive and seems as effective, MRI is replacing myelography. Considerations for patient positioning include prevention of untoward injury, such as pressure areas, pinch points on jointed tables, falls, wrong site surgery, and venous stasis. Ischemic insult to the area around the eye can result in blindness.14 A few prone positions simulate kneeling or crouching, which means that the patient may be in a full lift and body flexion before coming into contact with the surface of the OR bed. Figure 38-13 shows the kneeling-crouching position used by some surgeons for lower spine procedures. This posture constricts the patient’s circulation and increases the risk for embolization. The Jackson table (Fig. 38-14) and the Jackson-Wilson table with the central arch (Fig. 38-15) are used for posterior spinal incisions. Each type of specialty spinal table allows the surgeon to position the patient for optimal vertebral position and exposure of the surgical site.

Spinal surgery

Anatomy and physiology of the spinal cord and vertebral column

Curvatures of the spine

The spinal cord and spinal nerves

Vertebrae

Special considerations for spinal surgery

Diagnostics

Positioning for spinal surgery

Spinal surgery

Website

Website