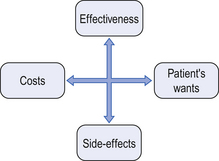

3 In attempting to understand the social and psychological aspects of treatment with medicines, we can to some extent apply the theoretical models for illness behaviour (see Ch. 2 and Fig. 3.1). The treatment process may be viewed from a macro- and a micro-perspective. The macro-perspective includes an analysis of the different systems and structural components in place to ensure a rational use of medicines, which is one of the primary goals of the system. The micro-perspective includes patient-related issues and the interaction between the patient and the healthcare professional. One medicine may fulfil one or more functions for an individual. Appropriateness refers to how a medicine is being prescribed and used in and by patients, including aspects such as appropriate indication, with no contraindications, appropriate dosage and administration. Duration of treatment should be optimal and the medicine should be correctly dispensed with appropriate and sufficient information and counselling (see Ch. 25). To achieve the intended effects, the medicine also needs to be correctly used by the patient. The economic aspect refers to a cost-effectiveness approach which needs to be applied, where all factors are assessed (see Ch. 22). A somewhat more expensive medicine may be preferable to a less expensive medicine, for example, because it has better treatment outcomes or fewer side-effects. Additionally, hidden costs, such as a need for more extensive laboratory tests, may increase the total cost of a particular treatment. The NMP can be seen as a guide for action, including the goals and priorities set by the government, and their main strategies and approaches. It also serves as a framework in the coordination of different activities. Depending on cultural, historical and socioeconomic factors there are differences in objectives, strategies and approaches between countries, but some common components can be identified. The goals for an NMP can be divided into: Registration of medicines is a key tool in assuring the safety, quality and efficacy of a new medicine being introduced on to the market and in defining the legal status of the medicinal product. The infrastructure that will assure quality, safety and efficacy involves the licensing and inspection of manufacturers, distributors and their premises, and setting professional working standards. There is wide international cooperation in this field among the different component authorities. Nevertheless, every now and then the media have reports about counterfeit products and toxic products sold to the public, sometimes with disastrous consequences (see Chs 22 and 51). Medicine use studies have been used to identify ‘irrational medicine use’, such as the overuse of psychotropics and antibiotics, where there has been inappropriate prescribing and unnecessary extended treatment periods. There has also been interest in the ‘underuse’ of medicines for major chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia. Underuse of medicines, together with misuse, whether deliberate or unintentional, has been one of the main focuses of patient adherence studies. From these studies we know something about the use of medicines and the clinical, social and economic consequences. During the last few years there have been attempts in both developed and developing countries to improve the knowledge and understanding about medicines among the general public. This can be seen as an attempt to influence and improve (from a medical point of view) social knowledge related to medicines and health in general. National campaigns such as ‘Ask about your medicines’ are good examples of this kind of activity. A more balanced partnership between consumer-patients and healthcare providers is one of the goals in such activities. This has been referred to as concordance (see Ch. 18). A better appreciation of the limits of medicines and a lessening of the belief that there is a ‘pill for every ill’ are examples of the goals of such efforts.

Socio-behavioural aspects of treatment with medicines

Societal perspectives on rational use of medicines

Societal perspectives on rational use of medicines

Factors affecting the treatment process with medicines

Factors affecting the treatment process with medicines

Sociological and behavioural aspects of use and prescribing of medicines

Sociological and behavioural aspects of use and prescribing of medicines

A sociological perspective of pharmacy and the pharmacy profession

A sociological perspective of pharmacy and the pharmacy profession

Introduction

Functions of medicines

Therapeutic function – the conventional use of medicines to prevent, treat and cure disease

Therapeutic function – the conventional use of medicines to prevent, treat and cure disease

Placebo function – to show concern for, and to satisfy the patient

Placebo function – to show concern for, and to satisfy the patient

Coping function – to relieve feelings of failure, stress, grief, sadness, loneliness

Coping function – to relieve feelings of failure, stress, grief, sadness, loneliness

Self-regulatory function – to exercise control over disorder or life

Self-regulatory function – to exercise control over disorder or life

Social control function – to manage behaviour of demanding or disruptive patients, hyperactive children

Social control function – to manage behaviour of demanding or disruptive patients, hyperactive children

Recreational function – to relax, enjoy the company of others, experience pleasurable feelings

Recreational function – to relax, enjoy the company of others, experience pleasurable feelings

Religious function – to seek religious meaning or experience

Religious function – to seek religious meaning or experience

Cosmetic function – to beautify skin, hair and body

Cosmetic function – to beautify skin, hair and body

Appetitive function – to allay hunger or control the desire for food

Appetitive function – to allay hunger or control the desire for food

Instrumental function – to improve academic, athletic or work performance

Instrumental function – to improve academic, athletic or work performance

Sexual function – to increase sexual ability

Sexual function – to increase sexual ability

Fertility function – to control fertility

Fertility function – to control fertility

Research function – to gain knowledge and understanding of human behaviour

Research function – to gain knowledge and understanding of human behaviour

Diagnostic function – to help make a diagnosis

Diagnostic function – to help make a diagnosis

Status-conferring function – to gain social status, prestige, income.

Status-conferring function – to gain social status, prestige, income.

A societal perspective on the rational use of medicines

Defining rational use

National medicines policy (NMP)

Health-related goals, which entail making essential medicines available, ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicines, and promoting rational prescribing, dispensing and use of medicines

Health-related goals, which entail making essential medicines available, ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of medicines, and promoting rational prescribing, dispensing and use of medicines

Economic goals, which may include lowering the cost of medicines and providing jobs in the pharmaceutical sector

Economic goals, which may include lowering the cost of medicines and providing jobs in the pharmaceutical sector

National development goals, which may include increasing the skills of personnel in pharmacy, medicine, etc. and encouraging industrial activities in the manufacturing of medicines.

National development goals, which may include increasing the skills of personnel in pharmacy, medicine, etc. and encouraging industrial activities in the manufacturing of medicines.

Ensuring the safety of medicines

Use of medicines

Improving public understanding of medicines

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree