SMALL ROUND BLUE CELL TUMORS

19.1 Ewing Sarcoma and Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor

19.4 Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma

19.1 Ewing Sarcoma and Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) was formerly considered a soft tissue variant of the osseous Ewing sarcoma (EWS). At one point, PNET was termed “extraosseous Ewing sarcoma.” Most recently, EWS and PNET have been reclassified as a single lesion based on similar histologic and molecular/cytogenetic features. Despite the consolidation of the nomenclature, the term “PNET” will probably remain in the clinical lexicon for several more years. For the sake of simplicity and in acknowledgment of the evolution of terminology, these two terms will be considered under the “umbrella category” of EWS.

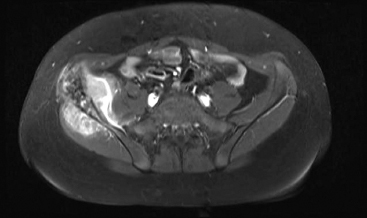

EWS represents the second most common malignant tumor of the pediatric population. Although all age groups are affected, there is a peak incidence of EWS between 8 and 25 years of age, and there is a slight male predominance. Previous clinicopathologic studies of EWS have commented on the relative rarity of this lesion in non-Caucasian individuals. When primary in bone, EWS tends to arise in sites associated with marrow production. As such, common sites of origin include the pelvis and ribs, as well as the metaphyseal or diaphyseal regions of the long bones (Figure 19.1.1). Less common sites include the skull, vertebral column, and scapula. An estimated 10% to 20% of cases are “extraosseous.” Frequent extraskeletal sites include the thigh, paraspinal musculature, and soft tissues of the foot. Symptoms of EWS most often relate to pain in the affected region. Occasionally, patients present with a concomitant fever and abnormal lab studies (relative leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate), leading to a false clinical impression of infection or osteomyelitis.

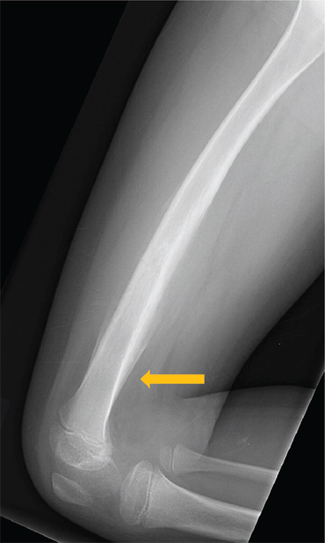

On imaging, osseous EWS is most often centered on the marrow cavity of the affected bone. EWS tends to be permeative and ill defined, but in more advanced cases, is associated with an obvious soft tissue mass. Periosteal reactions are additional common imaging features associated with EWS. Tumor cells eroding through the bone cortex often give rise to a distinctive “onion skinning” pattern of multilayered periosteal reaction (Figures 19.1.2 and 19.1.3). There may also be a “sunburst” pattern of periosteal growth that is oriented perpendicular to the host bone. A significant percentage of patients present with a pathologic fracture.

Prior to the development of radiation and chemotherapeutic treatment strategies for EWS, this was an aggressive and most often fatal disease. With modern treatment protocols, 5-year survival rates exceed 60%. Prognosis is related to tumor size and location (with centrally located tumors having the most dismal outcome) as well as patient age and stage at presentation. Unfortunately, about 25% of patients have demonstrable metastatic disease, usually in the lungs, at presentation. Some of the more effective treatment protocols for the treatment of EWS involve neoadjuvant multimodal therapy. As such, there is often intense pressure to confirm a diagnosis of EWS on small biopsy specimens.

EWS was the first sarcoma to demonstrate a consistent balanced translocation. The EWSR1 gene locus on chromosome 22 partners with a variety of other genes of the ETS family of transcription factors. Although several different partner genes have been identified, FLI1 and ERG are the most common, accounting for the majority of cases.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

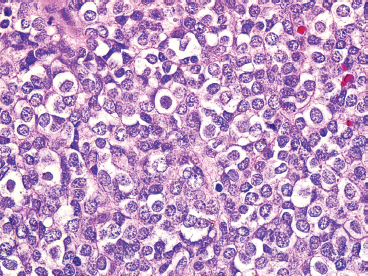

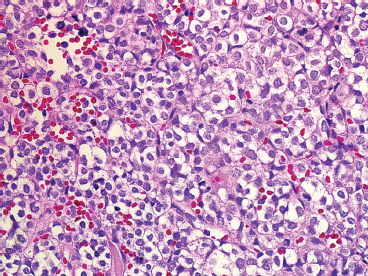

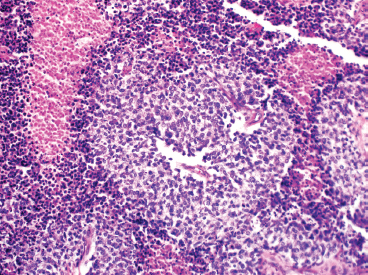

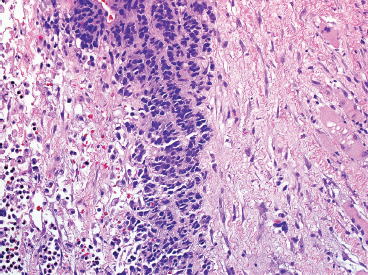

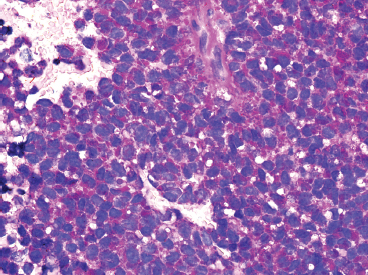

The microscopic appearance of EWS can have some subtle variation, but overall, EWS is one of the classic “small round blue cell tumors” (see also Tables 9.1.1 and 9.1.2). EWS grows as a solid sheet of cells without intervening stroma. The cells tend to be relatively uniform and are round with indistinct cytoplasm (Figure 19.1.4). Occasionally, the cytoplasm can have a clear appearance with distinctive cytoplasmic borders (Figure 19.1.5). One of the most frustrating features of EWS is that it often displays large areas of confluent necrosis (Figures 19.1.6 and 19.1.7), making adequacy assessments on small amounts of tissue very difficult. Rosette-like arrangements are one of the classic features of the old PNET category of tumors and are thought to correspond to neuroectodermal differentiation.

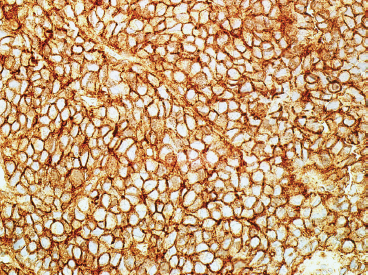

Immunohistochemical staining represents an important ancillary technique for accurately identifying EWS and separating it from some of the other small round blue cell tumors. EWS consistently stains for vimentin and CD99, the latter most commonly in a membranous pattern (Figure 19.1.8). Occasionally, positive markers include Bcl-2, S100 protein, CD56 and epithelial markers such as cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). Anti-FLI-1 is a newer marker that is more sensitive and specific, but not always available for routine use. One older and often overlooked ancillary test is the use of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain to demonstrate the presence of intracellular glycogen (Figure 19.1.9). Because the immunophenotype of EWS overlaps that of other sarcomas, it is often wise to confirm the presence of an EWSR1 translocation in diagnostically difficult cases. About 85% of EWSs are positive for the translocation. The so-called EWSR1-negative EWS may instead harbor an FUS fusion or may be one of the rare CIC-DUX4 tumors.

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

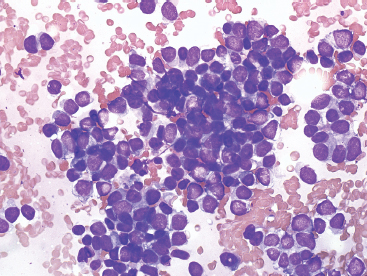

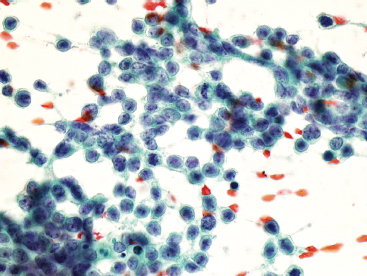

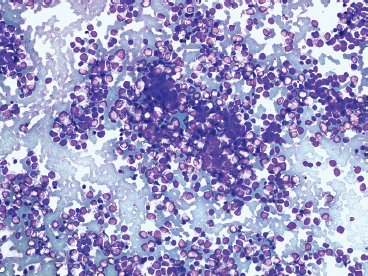

Aspirates of EWS are usually very cellular. There is often evidence of necrosis in the background, including ghost cells, pyknotic material, and debris. In addition, there may be extensive streaming of nuclear material, similar to that identified in aspirates of small cell carcinoma. Individual tumor cells are usually isolated, but in very cellular aspirates may be identified in small clusters. Intact, viable cells are small with very inconspicuous cytoplasm (Figure 19.1.10). Nuclear outlines, best appreciated in ethanol-fixed preparations, are often convoluted and irregular (Figure 19.1.11). Chromatin may be either fine or coarsely granular. Notably absent features include rosette formations and extensive nuclear molding.

Some cytologic descriptions of EWS stress the presence of two distinct cell populations: one being larger and possessing a cytoplasmic rim, and the other being smaller and more pyknotic, without cytoplasm. The variation in cell appearance may be related to individual cell viability (Figure 19.1.12).

FIGURE 19.1.1 A large Ewing sarcoma (EWS) arising from the iliac wing. The pelvic bones are fairly common sites for EWS.

FIGURE 19.1.2 EWS of the diaphysis of the femur. There is a prominent onion skinning type of periosteal reaction.

FIGURE 19.1.3 On the lateral view, a Codman’s triangle can be seen at the distal aspect of the lesion (arrow).

FIGURE 19.1.4 EWS is one of the prototypic small round blue cell tumors. Tumor cells are often arranged in solid masses.

FIGURE 19.1.5 In this variation of EWS histology, there is focal clearing of individual tumor cell cytoplasm.

FIGURE 19.1.6 EWS is notorious for having large foci of confluent necrosis. In this example, viable tumor is arranged around small vessels.

FIGURE 19.1.7 In this example, only a small focus of viable tumor is present in a single-file type of pattern.

FIGURE 19.1.8 Immunohistochemical staining for CD99 is typically present in a membranous pattern.

FIGURE 19.1.9 Histochemical staining for PAS reveals intracytoplasmic glycogen.

FIGURE 19.1.10 Aspirates of EWS are frequently very cellular and composed of intact as well as pyknotic tumor cells. This small round blue cell pattern is consistent with a wide range of diagnoses.

FIGURE 19.1.11 On fixed material, the nuclear features of EWS can be better appreciated. The nuclei often contain subtle nuclear irregularities. The chromatin is finely granular.

FIGURE 19.1.12 Often aspirates of EWS tend to have a “biphasic” look with two distinctive populations of cells. The smaller “cells” represent pyknotic material.

Primary bone lymphoma (PBL) is a relatively rare lesion, but represents an estimated 7% of all malignant bone tumors. PBL is usually a diffuse large B-cell type of lymphoma (DLBCL). Of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, PBL is estimated at less than 1% of all cases. The age range of patients is wide, but primary lymphoma of bone tends to occur in middle-aged adults. PBL tends to affect bone sites that have persistent red bone marrow. The long bones, particularly the femur, are the most common sites for lymphoma, but there are rare examples in the spine, pelvic bones, and craniofacial bones. Patients present with bone pain or, occasionally, pathologic fracture.

On imaging, the features are nonspecific. PBL tends to be metaphyseal based and to involve large portions of bone with variable areas of sclerosis, lysis, and cortical destruction (Figure 19.2.1). Magnetic resonance imaging studies often identify signal abnormalities in the marrow cavity contiguous to the main lesion.

Treatment of PBL is largely with chemotherapy and radiation. It is rare to see a resected PBL unless there has been a pathologic fracture. Prognosis of PBL is related to patient age (those under 60 tending to do better) as well as stage of disease and initial response to chemotherapy. Interestingly, the site of tumor involvement does not appear to affect prognosis.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree