SMALL ROUND BLUE CELL TUMORS

9.1 Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma

9.3 Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumor

9.5 Melanotic Neuroectodermal Tumor of Infancy

9.1 Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS) represents the most common subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma and the most frequent sarcoma of the pediatric population. The peak incidence of ERMS is in children under the age of 15, with about half of all cases arising in children under 5 years of age. ERMS may occasionally occur in adult patients.

About 50% of ERMS occur within the head and neck region. Favored sites include the orbital soft tissues, nasopharynx, and oral cavity. The remainder of ERMSs tend to occur in the genitourinary (GU) tract, and much less commonly in the soft tissues of the extremities. Rare examples of ERMS in the biliary tract, retroperitoneum, and pelvic or abdominal cavities have been documented. Symptoms are related to swelling or a mass effect on adjacent tissues. Proptosis, diplopia, and sinusitis are common presenting symptoms in the head and neck region. The presence of a tumor-like mass is more obvious with ERMSs that occur in the GU tract. A special subset of ERMS, typically known as sarcoma botryoides or botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma, presents as a fleshy “bag of grapes”-like lesion on clinical exam.

The prognosis for ERMS is generally good, particularly in patients without evidence of metastatic disease at the time of presentation. Age is also an independent predictor of outcome for ERMS; children between ages 1 and 9 do better than infants and adolescents. In addition, particular subcategories of ERMS, particularly the botryoid type, are associated with a better prognosis than the more conventional ERMS.

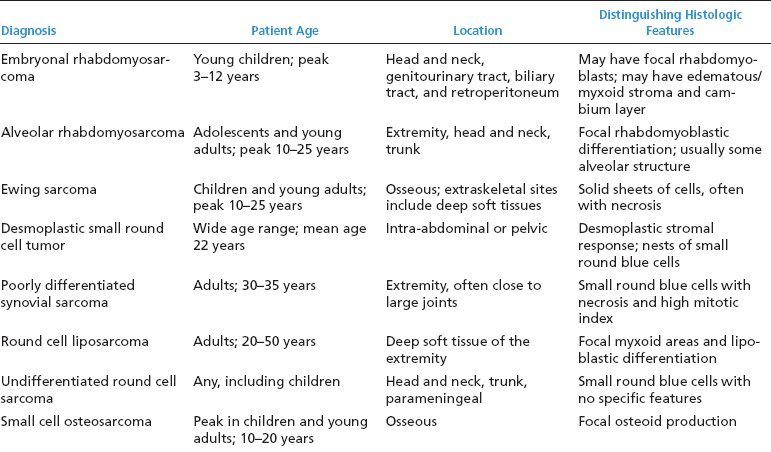

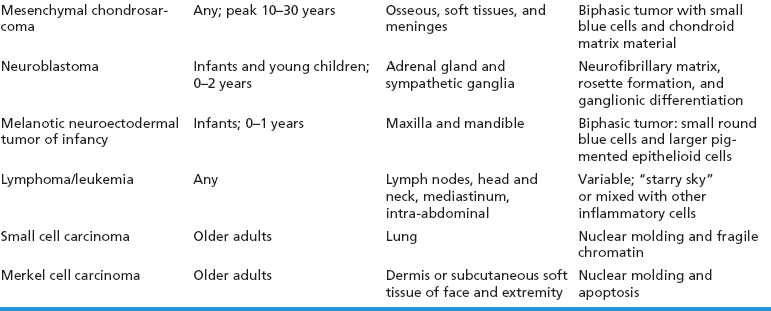

ERMSs as a group do not show specific reproducible cytogenetic or molecular aberrations that translate into an ancillary diagnostic test. Structural and numeric copy number changes of chromosomes 2, 8, and 13 are frequent findings. In addition, there is often an allelic loss at region 11p15, which is postulated to correspond to the site of a tumor suppressor gene or genes. Of note, it is critical to separate ERMS from the second most common variant, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS). Clinically, this distinction is critical as the two subtypes of rhabdomyosarcoma have different prognoses and different treatment regimens. A confounding feature is that ARMS can sometimes closely simulate ERMS on histology. Fortunately, ARMS is characterized by a translocation at the FOXO1 (formerly known as FKHR, for fork-head in rhabdomyosarcoma) gene locus, a feature that is diagnostically exploitable. A summary of the clinical and histologic features of ERMS and other small round blue cell tumors is given in Table 9.1.1

HISTOPATHOLOGY

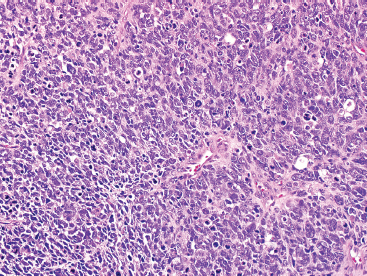

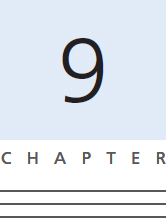

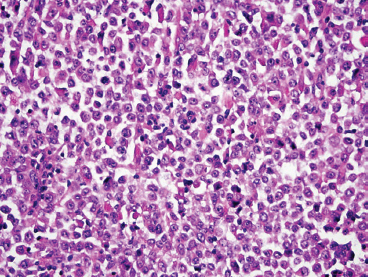

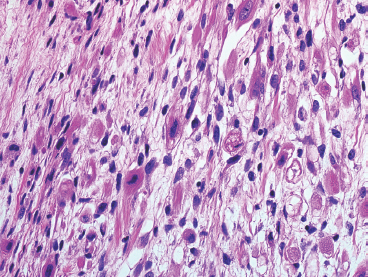

The histologic appearance of ERMS can be somewhat variable. In its most classic form, ERMS shows a small round blue cell type of morphology with very primitive rhabdomyoblasts. The cells may be compact or loosely arranged in an edematous stroma (Figure 9.1.1). Individual rhabdomyoblasts tend to have high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios but there is usually some evidence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation somewhere within the tumor. Often individual cells with a rim of bright eosinophilic cytoplasm are identified scattered throughout the tumor mass (Figure 9.1.2). Although most cells are round to oval in shape, there may be evidence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation with the formation of tadpole or “strap” cells. ERMS nuclei tend to be relatively monotonous in size, but there may be extensive nuclear membrane irregularity. The presence of numerous enlarged, hyperchromatic cells should raise the possibility of an “anaplastic” form of ERMS. Anaplastic ERMS may have bizarre, multipolar mitotic figures (Figure 9.1.3). The presence of a diffuse anaplastic component should be reported, as it represents an indicator of more aggressive behavior.

An additional variant of rhabdomyosarcoma that deserves special mention is the spindle cell subtype. This spindle cell variant occurs in pediatric patients and should not be confused with the “sclerosing” type of rhabdomyosarcoma that tends to affect adults. The spindle cell form of ERMS is characterized by sweeping fascicles of rhabdomyoblasts that contain more eosinophilic cytoplasm than their more conventional counterparts (Figure 9.1.4). In addition, the nuclei tend to be ovoid to elongate, rather than round, and often have slightly tapered but blunt-ended nuclei. Cross striations are usually easily identified within this subtype.

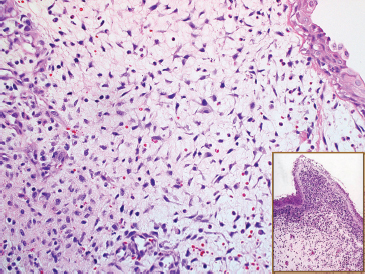

And finally, there is the botryoid subtype of ERMS. This is a common variant and has a tendency to occur in the mucosal surfaces of the GU tract (Figure 9.1.5). The histologic hallmark of this subtype is the presence of a compact proliferation of cells beneath the mucosal surface, forming a feature known as a “cambium layer.” The stroma of botryoid tumors is often very loose and myxoid.

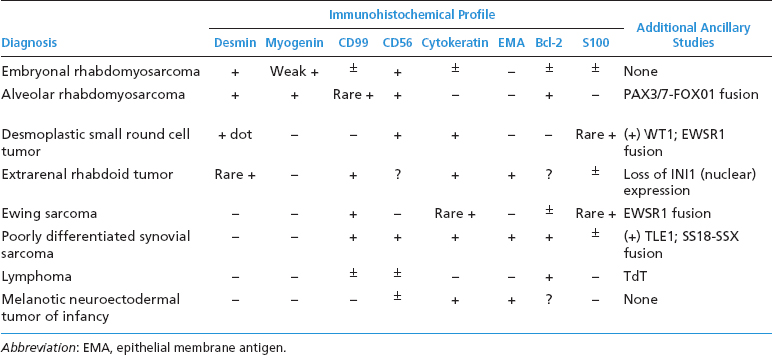

ERMS shows immunohistochemical evidence of muscle differentiation. It usually stains diffusely positively for desmin and other markers of skeletal differentiation. The immunohistochemical profile of ERMS and other small round blue cell tumors is outlined in Table 9.1.2.

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

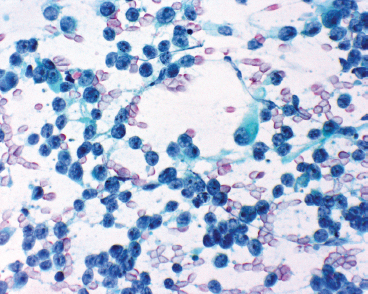

Aspirates of ERMS tend to be cellular and largely show a “small round blue cell” type of morphology. Cells tend to be largely discohesive or occasionally arranged in small clusters. There should not be any nuclear molding. Cells have an increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, with cytoplasm tending to be very inconspicuous to completely absent. Occasionally, there may be a frothy or “tigroid” type of background. On fixed preparations, the presence of cytoplasm can be identified more readily (Figure 9.1.6). In addition, the nuclear features are better demonstrated. Individual cell nuclei tend to be slightly irregular, and they contain speckled chromatin.

The distinction between ERMS and ARMS is very important for patient prognosis and treatment purposes. Because the histologic, cytologic, and immunophenotypic features of these two entities overlap substantially, it is often wise to rule out the possibility of an ARMS by performing fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (for FOXO1) on small samples of ERMS. A negative result is reassuring in this setting.

FIGURE 9.1.1 Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS) as a solid sheet of small round blue cells.

FIGURE 9.1.2 ERMS usually shows focal evidence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation in the form of bright eosinophilic cytoplasm.

FIGURE 9.1.3 An anaplastic ERMS with marked nuclear atypia and bizarre multipolar mitotic figures.

FIGURE 9.1.4 The spindle cell subtype of ERMS tends to have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, often with visible cross striations.

FIGURE 9.1.5 A submucosal “sarcoma botryoides” variant of ERMS. The inset illustrates the cambium layer.

FIGURE 9.1.6 Aspirates of ERMS usually have multiple small round blue cells, largely stripped of their cytoplasm. The nuclear chromatin is speckled with one or more nucleoli.

TABLE 9.1.1 Clinical and Histologic Differential Diagnosis of Small Round Cell Tumors

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is the second most common subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma, accounting for about 20% of all cases. This subtype is usually seen in a slightly older population than the embryonal subtype, but there is a significant overlap of age of affected patients. Adolescents and young adults are often diagnosed with this subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma. Unlike ERMS, ARMS often occurs in the extremities, with about 40% of all cases located in the deep soft tissues of the arm or leg (Figure 9.2.1). Another common site of involvement is the paraspinal musculature. ARMS is also frequently identified in some of the areas prone to ERMS, namely, the head and neck region and pelvis. Symptoms are usually related to a rapidly growing mass or obstruction by the tumor. Individuals afflicted with ARMS tend to be at a higher stage at presentation, and the tumor is often metastatic by the time it is discovered.

As mentioned previously, this is an aggressive neoplasm with a survival rate of less than 50%. The staging and prognostic criteria for rhabdomyosarcomas, including ARMS, are summarized in Tables 9.2.1 and 9.2.2. Because the treatment for ERMS and ARMS differ significantly, it is important to establish a definitive diagnosis of ARMS prior to initiation of therapeutic intervention. Fortunately, ARMS is characterized by a recurrent translocation in about 80% of the cases. This involves a fusion of the FOXO1 gene with either a PAX3 (most common) or PAX7 gene. The fusion gene protein is a potent transcriptional activator. A full 20% of ARMS will not display either of these translocations. This is known as the “translocation negative” or “fusion negative” variant of ARMS. Demonstration of the presence or absence of the translocation is important as the PAX-FOXO1 gene status appears to be an important predictor of prognosis and may be utilized to stratify patients into risk groups in the very near future.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Like ERMS, ARMS can display a variety of histologic patterns. In its classic form, ARMS is characterized by small nests of tumor cells separated by thin fibrovascular septae (Figures 9.2.2 and 9.2.3). The nests contain clusters of cells that tend to have an intact peripheral layer, but often show cell discohesiveness in the center of the nests (Figures 9.2.4 and 9.2.5). This feature produces a “picket fence” arrangement. The cells themselves are small, primitive-appearing rhabdomyoblasts. Pleomorphism is usually apparent in ARMS, and large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, occasionally with visible cross striations, are often found (Figures 9.2.6 and 9.2.7). In addition, there are often multinucleate or “wreath-like” cells present throughout the neoplasm. Some cases of classic ARMS display a marked cytoplasmic clearing and can mimic other types of sarcoma with clear cells, particularly alveolar soft part sarcoma or clear cell sarcoma.

One of the more common histologic variants of ARMS is the “solid” variant. In this subtype, the fibrovascular septal structures are absent or inconspicuous (Figures 9.2.8 and 9.2.9). In the solid pattern, there may be large sheets of primitive small round cells that can be difficult to distinguish from other small round blue cell tumors, particularly the embryonal variant of rhabdomyosarcoma. Features that are helpful in diagnosing the “solid” variant of ARMS include a propensity for this tumor to display strong and diffuse nuclear staining for the immunohistochemical marker myogenin (versus patchy or focal staining in ERMS). In addition, detection of one of the FOXO1 gene translocations is particularly helpful. Other markers of muscle differentiation, including desmin, and to some extent, MyoD1, are less helpful as they will stain positively in ERMS as well as ARMS (Figure 9.2.10). The immunohistochemical profile and ancillary testing features of ARMS are compared to some of the other more common small round blue cell neoplasms in Table 9.2.1.

A third histologic variant is one that combines features of both embryonal and alveolar subtypes. These often contain foci of small round cells in a myxoid stroma as well as cells in the classic nested appearance. These combined tumors are often the “fusion negative” type described earlier. According to current guidelines, these tumors should be considered alveolar subtype for treatment and prognostic purposes.

CYTOLOGIC FEATURES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree