Sensory System

Through the sensory system, a person receives stimuli that facilitate interaction with the surrounding world. Afferent pathways connect specialized sensory receptors in the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth to the brain—the final station for continuous processing of sensory stimuli. Alterations in sensory function may lead to dysfunctions of sight and hearing as well as smell, taste, balance, and coordination.

Pathophysiologic changes

Alterations can occur in sight, hearing, smell, taste, balance, and coordination.

VISION

Disorders of vision include alterations in ocular movement, visual acuity, accommodation, refraction, and color vision.

Ocular movement

The eyes constantly move to keep objects being viewed on the fovea, which is a small area of the retina that contains only cones and is responsible for the best peripheral visual acuity. The six extraocular muscles that move each eye are innervated by the oculomotor (III), trochlear (IV), and abducens (VI) cranial nerves. Alterations in ocular movement include strabismus, diplopia, and nystagmus.

Strabismus

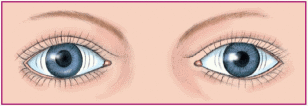

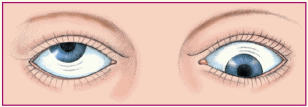

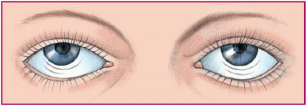

Strabismus occurs when one eye deviates from its normal position due to the absence of normal, parallel, or coordinated movement. The eyes may have an uncoordinated appearance, and the person may experience diplopia.

In children, types of strabismus are:

♦ concomitant (or nonparalytic), in which the degree of deviation doesn’t vary with the direction of gaze

♦ nonconcomitant (or paralytic), in which the degree of deviation varies with the direction of gaze

♦ congenital (present at birth or during the first 6 months)

♦ acquired (present during the first 2½ years)

♦ latent (phoria; apparent only when the child is tired or sick)

♦ constant.

Tropia, or constant strabismus, is divided into four categories: esotropia (inward deviation), exotropia (outward deviation), hypertropia (upward deviation), and hypotropia (downward deviation).

Strabismic amblyopia, lazy eye, is characterized by the loss of central vision in one eye; it typically results in esotropia (due to fixation in the dominant eye and suppression of images in the deviating eye). Strabismic amblyopia may result from hyperopia (farsightedness) or anisometropia (unequal refractive power).

Esotropia may result from muscle imbalance and may be congenital or acquired. In accommodative esotropia, the child’s attempt to compensate for the farsightedness affects the convergent reflex, and the eyes cross.

Strabismus is usually inherited, but its cause is unknown. In adults, strabismus may result from trauma. The incidence of strabismus is higher in patients with central nervous system

disorders, such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and Down syndrome.

disorders, such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and Down syndrome.

Muscle imbalances may be corrected by glasses, patching, or surgery, depending on the cause. However, residual defects in vision and extraocular muscle alignment may persist even after treatment.

Diplopia

Diplopia, or double vision, results when the extraocular muscles fail to work together and images fall on noncorresponding parts of the retinas. Diplopia usually begins intermittently or affects near or far vision exclusively. It can be classified as monocular (persisting when one eye is covered) or, more commonly, binocular (clearing when one eye is covered). Monocular diplopia may result from an early cataract, retinal edema or scarring, subluxated lens (partial dislocation of the lens of the eye), poorly fitting contact lens, or uncorrected refractive error. Binocular diplopia may result from ocular deviation or displacement, extraocular muscle palsies, or psychoneurosis, or after retinal surgery. Other causes of binocular diplopia include infection, neoplastic disease, metabolic disorders, degenerative disease, inflammatory disorders, and vascular disease.

Nystagmus

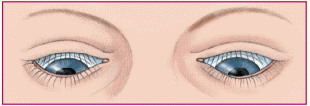

Nystagmus refers to involuntary oscillations or alternating movements of one or both eyes. These oscillations are usually rhythmic and may be horizontal, vertical, rotary, or mixed. They may be transient or sustained and may occur spontaneously or on deviation or fixation. Nystagmus may be classified as pendular (oscillations are equal in rate in both directions) or jerk (faster movements in one direction than in the opposite direction). Nystagmoid movements usually have a fast and a slow component. The direction of the nystagmus is given by the fast component. (See Classifying nystagmus, page 544.)

Nystagmus is a supranuclear ocular palsy resulting from pathology in the visual perceptual area, vestibular system, or cerebellum. Causes of nystagmus include brain stem or cerebellar lesions, labyrinthine disease, stroke, encephalitis, Ménière’s disease, multiple sclerosis, trauma, and alcohol and drug toxicity, including barbiturate, phenytoin (Dilantin), or carbamazepine (Tegretol) toxicity.

Visual acuity

Visual acuity refers to the ability to see clearly. A lack of visual acuity is commonly associated with refractive errors. In nearsightedness, or myopia, the eye focuses the visual image in front of the retina, causing objects in close view to be seen clearly and those at a distance to be blurry. In farsightedness, or hyperopia, the eye focuses the visual image behind the retina, causing objects in close view to be blurry and those at a distance to be clear. Both these problems are caused by an alteration in the shape of the eyeball. Other causes of reduced visual acuity include aging, amblyopia, cataracts, glaucoma, papilledema, dark adaptation, and scotoma (an area of diminished visual acuity surrounded by an area of normal vision within the visual field).

Amblyopia is severely decreased visual acuity or virtual blindness in a structurally intact eye. It occurs when there is interference in the stimulation of the vision-receptive cells in the brain. When normally stimulated, these cells allow for sensory development of visual acuity. Amblyopia is a form of treatable vision loss if recognized early. Causes may include strabismus, congenital cataract, abnormal refractive error, tumor, trauma, or infection.

If amblyopia is detected and treated before age 5, cure is almost assured. Treatment begun after age 10 is rarely successful.

If amblyopia is detected and treated before age 5, cure is almost assured. Treatment begun after age 10 is rarely successful.Accommodation

Accommodation occurs as the thickness of the eye’s lens changes to maintain visual acuity. For near vision, the ciliary body contracts and relaxes the zonules, the lens becomes spherical, the pupil constricts, and the eyes converge. For far vision, the ciliary body relaxes, the zonules tighten, the lens becomes flatter, the eyes straighten, and the pupils dilate. The oculomotor nerve and coordinated brain stem pathways account for accommodation. Alterations in accommodation may be caused by pressure, inflammation, aging, or disorders affecting the

oculomotor nerve. The result of impaired accommodation may be diplopia, blurred vision, or headache.

oculomotor nerve. The result of impaired accommodation may be diplopia, blurred vision, or headache.

Nystagmus is classified as pendular or jerk. Each type has further classifications.

Pendular nystagmus

Oscillating: slow, steady oscillations of equal velocity around a center point; caused by congenital loss of visual acuity or multiple sclerosis.

|

Vertical or seesaw: rapid, seesaw movement in which one eye appears to rise while the other appears to fall; suggests an optic chiasm lesion.

|

Jerk nystagmus

Convergence-retraction: irregular jerking of the eyes back into the orbit during upward gaze; can reflect midbrain tegmental (roof of the midbrain) damage.

|

Downbeat: irregular downward jerking of the eyes during downward gaze; can signal lower medullary damage.

|

Vestibular: horizontal or rotary movements of the eyes; suggests vestibular disease or cochlear dysfunction.

|

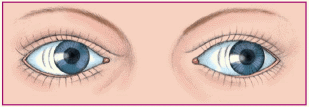

Refraction

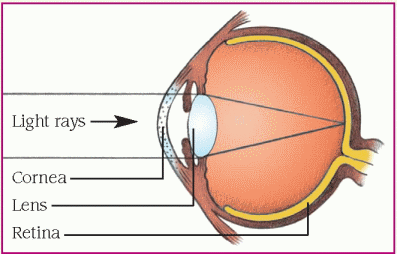

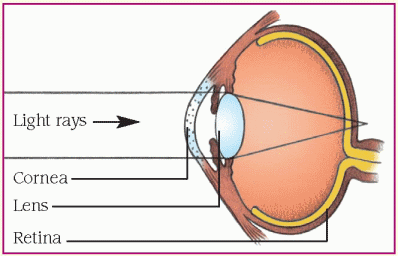

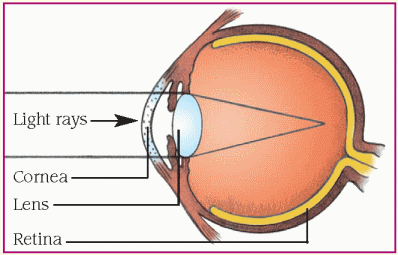

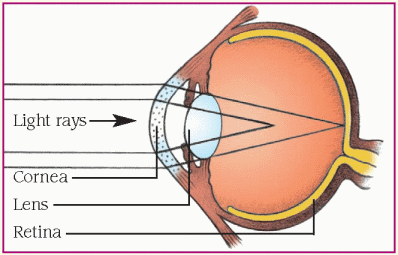

Refraction is the process of bending light rays so that they fall on the retina. As rays of light reach the surface of the cornea from all directions, the cornea directs them toward the lens. The lens further bends the light and directs the light rays to one spot on the retina. The greater the refractive power, the more the light rays are bent. Emmetropia is a condition in which light rays fall exactly on the retina. Alterations in refraction occur when light isn’t properly focused. Causes include abnormalities in curvature of the cornea, focusing of the lens, and eye length. Results include myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism. (See Refractive errors.)

Myopia

Myopia, or nearsightedness, occurs when light rays focus in front of the retina. Near objects can be seen clearly, and distant objects appear blurry. This condition may occur if the eye is too long or the refractive power of the cornea or lens is too great.

Myopia may also occur if hyperglycemia in uncontrolled diabetes causes lens swelling. A concave lens that bends light rays outward is used to correct myopia.

Hyperopia

Hyperopia, or farsightedness, occurs when light rays focus behind the retina. Distant objects appear clear, and nearby objects are blurred. This condition occurs when the eye is too short or the refractive power of the cornea or lens is too low. It may be corrected with a convex lens that bends light rays inward.

Presbyopia is a form of hyperopia that begins in middle age as the lens becomes firm and loses its elasticity. As a result, the refractive power of the lens is reduced, the eye loses its ability to accommodate, and near objects appear blurred. This condition is treated with a convex lens that bends light rays in different directions so they focus in a single point.

Presbyopia is a form of hyperopia that begins in middle age as the lens becomes firm and loses its elasticity. As a result, the refractive power of the lens is reduced, the eye loses its ability to accommodate, and near objects appear blurred. This condition is treated with a convex lens that bends light rays in different directions so they focus in a single point.Astigmatism

Astigmatism occurs when unequal curvature of the cornea or eyeball causes light rays to focus on different points on the retina, resulting in distorted images. Astigmatism may occur in conjunction with other refractive disorders.

Color vision

The retina’s cones are responsible for color vision. Each cone contains one of three different pigments (red, green, or blue) that absorb light waves of different wavelengths.

Color blindness is inherited on the X chromosome and therefore usually affects males. Acquired color blindness may also be due to

diabetes, bilateral strokes affecting the ventral portion of the occipital lobe, or disease of the macula or optic nerve.

diabetes, bilateral strokes affecting the ventral portion of the occipital lobe, or disease of the macula or optic nerve.

HEARING

Sound waves normally enter the external auditory canal, then travel to the tympanic membrane in the middle ear, causing it to vibrate. This vibration causes the malleus to move, setting in motion the incus and, in turn, the stapes. The malleus, incus, and stapes are collectively referred to as the ossicles. The stapes presses on the oval window of the inner ear, setting in motion the fluid of the cochlea and stimulating hair cells. The hair cells carry impulses through the cochlear division of the auditory cranial nerve (VIII) to the brain. This type of sound transmission to the inner ear, called air conduction, is usually better than transmission through bone (bone conduction).

Alterations in hearing are classified as conductive or sensorineural. Mixed hearing loss combines aspects of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

TASTE AND SMELL

The senses of taste and smell are also subject to alterations.

Taste

The sensory receptors for taste are the taste buds, concentrated over the surface of the tongue and scattered over the palate, pharynx, and larynx. These buds can differentiate among sweet, salty, sour, and bitter stimuli. Taste and olfactory receptors together perceive more complex flavors. Much of what’s considered taste is actually smell; food odors typically stimulate the olfactory system more strongly than related food tastes stimulate the taste buds.

A factor interrupting the transmission of taste stimuli to the brain may cause taste abnormalities. Taste abnormalities may result from trauma, infection, vitamin or mineral deficiencies, neurologic or oral disorders, and the effects of drugs. Moreover, because tastes are most accurately perceived in a fluid medium, dryness of the mouth may interfere with taste. Two major pathologic causes of impaired taste are aging, which normally reduces the number of taste buds, and heavy smoking (especially pipe smoking), which dries the tongue.

Alterations in taste may include:

♦ ageusia—a complete loss of taste

♦ hypogeusia—a partial loss of taste

♦ dysgeusia—a distorted sense of taste

♦ cacogeusia—an unpleasant or revolting taste of food.

Smell

As air travels between the septum and the turbinates of the nose, it touches sensory hairs (cilia) and olfactory nerve endings in the mucosal surface. The resultant stimulation of cranial nerve I sends impulses to the olfactoryreceiving area, primarily in the frontal cortex. Temporary impairment in the sense of smell can result from a condition that irritates and causes swelling of the nasal mucosa and obstructs the olfactory area in the nose, such as heavy smoking, rhinitis, or sinusitis. Permanent alterations in the sense of smell usually result when the olfactory neuroepithelium or a part of the olfactory nerve is destroyed. Permanent or temporary loss can also result from inhaling irritants, such as cocaine or acid fumes, that paralyze nasal cilia. Conditions such as aging, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or Kallmann’s syndrome (a congenital disorder) also may alter the sense of smell. Because combined stimulation of taste buds and olfactory cells produces the sense of taste, the loss of the sense of smell is usually accompanied by the loss of the sense of taste.

Alterations in smell include:

♦ anosmia—a total loss of the sense of smell

♦ hyposmia—an impaired sense of smell

♦ parosmia—an abnormal sense of smell.

Disorders

The most common disorders of vision are agerelated macular degeneration, cataract, and glaucoma. Other common sensory disorders include hearing loss, Ménière’s disease, and otosclerosis.

AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION

Macular degeneration—atrophy or degeneration of the macular disk—is the most common cause of legal blindness in adults age 50 and older. It’s also one of the causes of severe irreversible and unpreventable loss of central vision in elderly people.

Two types of age-related macular degeneration occur. The dry, or atrophic, form is characterized by atrophic pigment epithelial changes and typically causes mild, gradual visual loss. The wet, exudative form rapidly causes severe vision loss. It’s characterized by the subretinal formation of new blood vessels (neovascularization) that cause leakage, hemorrhage, and fibrovascular scar formation.

Causes

The causes of macular degeneration are unknown but may include:

♦ aging

♦ infection

♦ inflammation

♦ injury

♦ nutrition.

Pathophysiology

Age-related macular degeneration results from hardening and obstruction of retinal arteries, which probably reflect normal degenerative changes. The formation of new blood vessels in the macular area obscures central vision. Underlying pathologic changes occur primarily in the retinal pigment epithelium, Bruch’s membrane, and choriocapillaries in the macular region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree