Reproductive system

The reproductive system must function properly to ensure survival of the species. The male reproductive system produces sperm and delivers them to the female reproductive tract. The female reproductive system produces the ovum. If a sperm fertilizes an ovum, this system also nurtures and protects the embryo and developing fetus and delivers it at birth. The functioning of the reproductive system is determined not only by anatomic structure but also by complex hormonal, neurologic, vascular, and psychogenic factors.

Anatomically, the main distinction between the male and female is the presence of conspicuous external genitalia in the male. In contrast, the major reproductive organs of the female lie within the pelvic cavity.

Male reproductive system

The male reproductive system consists of the organs that produce and maintain sperm, transfer mature sperm from the testes, and introduce them into the female reproductive tract, where fertilization occurs.

Besides supplying male sex cells (in a process called spermatogenesis), the male reproductive system plays a part in the secretion of male sex hormones. The penis also functions in urine elimination.

In males, the reproductive and urinary systems are structurally integrated; most disorders, therefore, affect both systems. Congenital abnormalities or prostate enlargement may impair both sexual and urinary function. Abnormal findings in the pelvic area may result from pathologic changes in other organ systems, such as the upper urinary and GI tracts, endocrine glands, and neuromusculoskeletal system.

REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

The male reproductive organs include the penis, scrotum, testes, duct system, and accessory reproductive glands.

Penis

The penis consists of three cylinders of erectile tissue: two corpora cavernosa, and the corpus spongiosum, which contains the urethra. The glans, or tip, of the penis contains the urethral meatus, through which urine and semen pass to the exterior, and many nerve endings for sexual sensation. In uncircumcised males, the glans is covered by a loose, hoodlike fold of skin called the prepuce or foreskin. Smegma, a secretion of the glans, may collect in this area.

Scrotum

The scrotum, which contains the testes, epididymis, and lower spermatic cords, maintains the proper testicular temperature for spermatogenesis through relaxation and contraction. This is important because excessive heat reduces the sperm count.

Testes

The testes (also called gonads, which is a term for any reproductive organ, or testicles) produce sperm in the seminiferous tubules. Complete spermatogenesis develops in most males by age 15 or 16.

The testes form in the abdominal cavity of the fetus and complete final descent into the scrotum during the 7th month of gestation.

The testes produce and secrete hormones, especially testosterone, in their interstitial cells (Leydig’s cells). Testosterone affects the development and maintenance of secondary sex characteristics and sex drive. It also regulates metabolism, stimulates protein anabolism (encouraging skeletal growth and muscular development), inhibits pituitary secretion of the gonadotropins (follicle-stimulating hormone and interstitial cell-stimulating hormone), promotes potassium excretion, and mildly influences renal sodium reabsorption.

Duct system

The vas deferens connects the epididymis, in which sperm mature and ripen for up to 6 weeks, and the ejaculatory ducts. The seminal vesicles—two convoluted membranous pouches—secrete a viscous liquid of fructoserich semen, which provides energy for sperm; and prostaglandins, which probably facilitate fertilization.

Accessory reproductive glands

The prostate gland secretes the thin alkaline substance that comprises most of the seminal fluid; this fluid also protects sperm from acidity in the male urethra and in the vagina, thus increasing sperm motility.

The bulbourethral (Cowper’s) glands secrete an alkaline ejaculatory fluid, probably similar in function to that produced by the prostate gland. The spermatic cords are cylindrical fibrous coverings in the inguinal canal containing the vas deferens, blood vessels, and nerves.

Female reproductive system

Female reproductive structures include the mammary glands, external genitalia, and internal genitalia. Hormonal influences determine the development and function of these structures and affect fertility, childbearing, and the ability to experience sexual pleasure.

In no other part of the body do so many interrelated physiologic functions occur in such proximity as in the area of the female reproductive tract. Besides the internal genitalia, the female pelvis contains the organs of the urinary and GI systems (bladder, ureters, urethra, sigmoid colon, and rectum). The reproductive tract and its surrounding area are thus the site of urination, defecation, menstruation, ovulation, copulation, impregnation, and parturition.

MAMMARY GLANDS

Located in the breasts, the mammary glands are specialized accessory glands that secrete milk. Although present in both sexes, they normally function only in females.

EXTERNAL STRUCTURES

Female genitalia include the following external structures, collectively known as the vulva: mons pubis (or mons veneris), labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and the vestibule. The perineum is the external region between the vulva and the anus. The size, shape, and color of these structures —as well as pubic hair distribution and skin texture and pigmentation—vary greatly among individuals. Furthermore, these external structures undergo distinct changes during the life cycle.

Mons pubis

The mons pubis is the pad of fat over the symphysis pubis (pubic bone), which is usually covered by the base of the inverted triangular patch of pubic hair that grows over the vulva after puberty.

Labia majora

The labia majora are the two thick, longitudinal folds of fatty tissue that extend from the mons pubis to the posterior aspect of the perineum. The labia majora protect the perineum and contain large sebaceous glands that help maintain lubrication. Virtually absent in the young child, their development is a characteristic sign of onset of puberty. The skin of the more prominent parts of the labia majora is pigmented and darkens after puberty.

Labia minora

The labia minora are the two thin, longitudinal folds of skin that border the vestibule. Firmer than the labia majora, they extend from the clitoris to the posterior fourchette.

Clitoris

The clitoris is the small, protuberant organ located just beneath the arch of the mons pubis. The clitoris contains erectile tissue, venous cavernous spaces, and specialized sensory corpuscles that are stimulated during coitus. It’s homologous to the male penis.

Vestibule

The vestibule is the oval space bordered by the clitoris, labia minora, and fourchette. The urethral meatus is located in the anterior portion of the vestibule, and the vaginal meatus is in the posterior portion. The hymen is the elastic membrane that partially obstructs the vaginal

meatus in virgins. Its absence doesn’t necessarily imply a history of coitus, nor does its presence obstruct menstrual blood flow.

meatus in virgins. Its absence doesn’t necessarily imply a history of coitus, nor does its presence obstruct menstrual blood flow.

Several glands lubricate the vestibule. Skene’s glands (also known as the paraurethral glands) open on both sides of the urethral meatus; Bartholin’s glands, on both sides of the vaginal meatus.

The fourchette is the posterior junction of the labia majora and labia minora. The perineum, which includes the underlying muscles and fascia, is the external surface of the floor of the pelvis, extending from the fourchette to the anus.

INTERNAL STRUCTURES

The internal structures of the female genitalia include the vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes (or oviducts), and ovaries.

Vagina

The vagina occupies the space between the bladder and the rectum. A muscular, membranous tube 2″ to 3″ (5 to 7.5 cm) in length, the vagina connects the uterus with the vestibule of the external genitalia. It serves as a passageway for sperm to the fallopian tubes, a conduit for the discharge of menstrual fluid, and the birth canal during parturition.

Cervix

The cervix, the narrow neck of the uterus, is the most inferior part of the vagina, protruding into the vaginal canal. The cervix provides a passageway between the vagina and the uterine cavity.

Uterus

The uterus is the hollow, pear-shaped organ in which the fetus grows during pregnancy. The thick uterine wall consists of mucosal, muscular, and serous layers. The inner mucosal lining (the endometrium) undergoes cyclic changes (based on hormonal activity) to facilitate and maintain pregnancy.

The smooth-muscle middle layer (the myometrium) interlaces the uterine and ovarian arteries and veins that circulate blood through the uterus. During pregnancy, this vascular system expands dramatically. After abortion or childbirth, the myometrium contracts to constrict the vasculature and control loss of blood.

The outer serous layer (the parietal peritoneum) covers all of the fundus, part of the corpus, but none of the cervix. This incompleteness allows surgical entry into the uterus without incision of the peritoneum, thus reducing the risk of peritonitis in the days before effective antibiotic therapy.

Fallopian tubes

The two fallopian tubes extend from the sides of the fundus and terminate near the ovaries. Each tube has a fimbriated (fringelike) end adjacent to the ovary that serves to capture an oocyte after ovulation. Through ciliary and muscular action, these small tubes carry ova from the ovaries to the uterus and facilitate the movement of sperm from the uterus toward the ovaries. The same ciliary and muscular action helps move a zygote (fertilized ovum) down to the uterus, where it may implant in the bloodrich inner uterine lining, the endometrium.

Ovaries

The ovaries are two almond-shaped organs, one on either side of the pelvis, situated behind and below the fallopian tubes. The ovaries produce ova and two primary hormones—estrogen and progesterone—in addition to small amounts of androgen. These hormones in turn produce and maintain secondary sex characteristics, prepare the uterus for pregnancy, and stimulate mammary gland development. The ovaries are connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament.

In the 30th week of gestation, the fetus has about 7 million follicles, which degenerate, leaving about 2 million present at birth. By puberty, only 400,000 remain, and these ova precursors become graafian follicles in response to the effects of pituitary gonadotropic hormones (follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH] and luteinizing hormone [LH]). Fewer than 500 of each woman’s ova mature and become potentially fertile.

THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Maturation of the hypothalamus and the resultant increase in hormone levels initiate puberty. In the young girl, the appearance of pubic and axillary hair (pubarche) and the characteristic adolescent growth spurt follow breast development (thelarche)—the first sign of puberty. The reproductive system begins to undergo a series of hormone-induced changes that result in menarche, or the onset of menstruation (or menses).

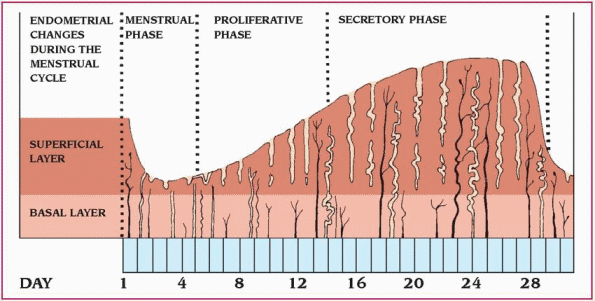

The menstrual cycle consists of three different phases: menstrual, proliferative (estrogen dominated), and secretory (progesterone dominated). (See Understanding the menstrual cycle.)

At the end of the secretory phase, the uterine lining is ready to receive and nourish a zygote. If fertilization doesn’t occur, increasing estrogen and progesterone levels decrease LH and FSH production. Because LH is needed to maintain

the corpus luteum, a decrease in LH production causes the corpus luteum to atrophy and halt the secretion of estrogen and progesterone. The thickened uterine lining then begins to slough off, and menstruation begins.

the corpus luteum, a decrease in LH production causes the corpus luteum to atrophy and halt the secretion of estrogen and progesterone. The thickened uterine lining then begins to slough off, and menstruation begins.

The menstrual cycle is divided into three distinct phases.

♦ During the menstrual phase, which starts on the first day of menstruation, the top layer of the endometrium breaks down and flows out of the body. This flow, the menses, consists of blood, mucus, and unneeded tissue.

♦ During the proliferative (follicular) phase, the endometrium begins to thicken, and the level of estrogen in the blood increases, surging at midcycle. Then estrogen production decreases, the follicle matures, and ovulation occurs.

♦ During the secretory (luteal) phase, the endometrium begins to thicken to nourish an embryo should fertilization occur. Without fertilization, the top layer of the endometrium breaks down and the menstrual phase of the cycle begins again.

|

In the nonpregnant female, LH controls the secretions of the corpus luteum, thereby increasing the amount of progesterone in the bloodstream. In the pregnant woman, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), produced by the nascent placenta, controls these secretions.

If fertilization and pregnancy occur, the endometrium grows even thicker and vascular ingrowth occurs. After implantation of the zygote (5 to 6 days after fertilization), the endometrium becomes the decidua. Trophoblastic cells produce hCG soon after implantation, stimulating the corpus luteum to continue secreting estrogen and progesterone, which prevents further ovulation and menstruation.

hCG continues to stimulate the corpus luteum until the placenta (the vascular organ that develops to transport materials to and from the fetus) forms and starts producing its own estrogen and progesterone. After the placenta takes over hormone production, secretions of the corpus luteum are no longer needed to maintain the pregnancy, and the corpus luteum gradually decreases its function and begins to degenerate. This is termed luteoplacental shift and commonly occurs by the end of the first trimester.

Pathophysiologic changes

Alterations may occur in the structure, process, or function of both the male and female reproductive systems.

SEXUAL MATURATION ALTERATIONS

Sexual maturation, or puberty, can be affected by various congenital and endocrine disorders. The timing of puberty may be too early (precocious

puberty) or too late (delayed puberty). Precocious puberty is the onset of sexual maturation before age 9 in boys and before age 6 in girls. It’s more common in girls than in boys. The cause is usually idiopathic but can result from central nervous system or congenital abnormalities.

puberty) or too late (delayed puberty). Precocious puberty is the onset of sexual maturation before age 9 in boys and before age 6 in girls. It’s more common in girls than in boys. The cause is usually idiopathic but can result from central nervous system or congenital abnormalities.

In delayed puberty, there’s no evidence of the development of secondary sex characteristics in boys by age 14 or girls by age 13. There’s usually no evidence of hormonal abnormalities. The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, a system that stimulates and regulates the production of hormones necessary for normal sexual development and function, is intact, but maturation is slow. The cause is unknown.

HORMONAL ALTERATIONS

Complex hormonal interactions determine the normal function of the female reproductive tract and require an intact hypothalamic-pituitaryovarian axis. A defect or malfunction of this system can cause infertility due to insufficient gonadotropin secretions (both LH and FSH). The ovary controls—and is controlled by—the hypothalamus through a system of negative and positive feedback mediated by estrogen production. Insufficient gonadotropin levels may result from infections, tumors, or neurologic disease of the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. A mild hormonal imbalance in gonadotropin production and regulation, possibly caused by polycystic disease of the ovary or abnormalities in the adrenal or thyroid gland that adversely affect hypothalamic-pituitary functioning, may sporadically inhibit ovulation. Because gonadotropins are released in a pulsatile fashion, a significant disturbance in this pulsatility will adversely affect ovulatory function. Marijuana use can delay the onset of puberty because it blocks the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus, which ultimately delays gonadal function.

Male hypogonadism, or an abnormal decrease in gonad size and function, results from decreased androgen production in males, which may impair spermatogenesis (causing infertility) and inhibit the development of normal secondary sex characteristics. The clinical effects of androgen deficiency depend on age at onset. Primary hypogonadism results directly from interstitial (Leydig’s cell) cellular or seminiferous tubular damage of the testes due to faulty development or mechanical damage. Androgen deficiency causes increased secretion of gonadotropins by the pituitary in an attempt to increase the testicular functional state and is therefore termed hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. This form of hypogonadism includes Klinefelter’s syndrome (47 XXY), Reifenstein’s syndrome, male Turner’s syndrome, Sertoli-cell-only syndrome, anorchism, orchitis, and aftereffects of irradiation.

Secondary hypogonadism is due to faulty interaction within the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, resulting in failure to secrete a normal level of gonadotropins, and is therefore termed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. This form of hypogonadism includes hypopituitarism, isolated FSH deficiency, isolated LH deficiency, Kallmann’s syndrome, and Prader-Willi syndrome. Depending on the patient’s age at onset, hypogonadism may cause eunuchism (complete gonadal failure) or eunuchoidism (partial failure).

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the specific cause of hypogonadism. Some characteristic findings may include delayed bone maturation; delayed puberty; infantile penis and small, soft testes; less than average muscle development and strength; fine, sparse facial hair; scant or absent axillary, pubic, and body hair; and a high-pitched, effeminate voice. In an adult, hypogonadism diminishes sex drive and potency and causes regression of secondary sex characteristics.

MENSTRUAL ALTERATIONS

Alterations in menstruation include the absence of menses, abnormal bleeding patterns, or painful menstruation. Menopause is the cessation of menstruation. It results from a complex continuum of physiologic changes —the climacteric —caused by declining ovarian function. The climacteric produces various changes in the body, the most dramatic being the cessation of menses.

The climacteric, a normal gradual reduction in ovarian function due to aging, begins in most women between ages 45 and 50. Perimenopause begins 5 to 10 years (sometimes more) before menopause and commenses with vasomotor symptoms and irregular menses. Menopause begins 12 months after final menses and is characterized by the continuation of vasomotor symptoms as well as urogenital symptoms (vaginal dryness and dyspareunia).

The climacteric, a normal gradual reduction in ovarian function due to aging, begins in most women between ages 45 and 50. Perimenopause begins 5 to 10 years (sometimes more) before menopause and commenses with vasomotor symptoms and irregular menses. Menopause begins 12 months after final menses and is characterized by the continuation of vasomotor symptoms as well as urogenital symptoms (vaginal dryness and dyspareunia).Premature ovarian failure, or premature menopause, the gradual or abrupt cessation of menstruation before age 40, occurs without apparent cause in about 1% of women in the United States. Factors that may precipitate premature ovarian failure include malnutrition, debilitation, extreme emotional stress, pelvic irradiation, viral agents, and surgical procedures that impair ovarian blood supply. Artificial menopause may follow radiation therapy or surgical procedures, such as removal of both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy). Other causes

of premature ovarian failure include a decreased number of germ cells, chromosomal abnormalities, gonadotropin secretion defects, and autoimmune disorders. Hysterectomy decreases the interval before menopause, even when the ovaries aren’t removed. It’s speculated that hysterectomy may decrease ovarian blood flow in some fashion.

of premature ovarian failure include a decreased number of germ cells, chromosomal abnormalities, gonadotropin secretion defects, and autoimmune disorders. Hysterectomy decreases the interval before menopause, even when the ovaries aren’t removed. It’s speculated that hysterectomy may decrease ovarian blood flow in some fashion.

Ovarian failure, in which no ova are produced, may result from a functional ovarian disorder from premature ovarian failure. Amenorrhea is a natural consequence of ovarian failure.

Pain is commonly associated with the menstrual cycle; in many common diseases of the female reproductive tract, such pain may follow a cyclic pattern. A patient with endometriosis, for example, may report increasing premenstrual pain that decreases at the end of menstruation. For a description of the types of abnormal menstrual bleeding, (see Abnormal premenopausal bleeding.)

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Sexual dysfunction includes arousal problems, orgasmic problems, and sexual pain (dyspareunia, vaginismus). Dysfunction may be caused by a general medical condition, psychological condition, substance use or abuse, or a combination of these factors.

Arousal disorder is an inability to experience sexual pleasure. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), the essential feature is a persistent or recurrent inability to attain or to maintain an adequate lubricationswelling response of sexual excitement until completion of the sexual act. Orgasmic disorder, according to the DSM-IV-TR, is a persistent or recurrent delay in or absence of orgasm after a normal sexual excitement phase.

Both arousal and orgasmic disorders are considered primary if they exist in a female who has never experienced sexual arousal or orgasm; they’re secondary when a physical, mental, or situational condition has inhibited or obliterated a previously normal sexual function. The prognosis is good for temporary or mild disorders resulting from misinformation or situational stress but is guarded for disorders that result from intense anxiety, chronically discordant relationships, psychological disturbances, or drug or alcohol abuse in either partner.

The following factors, alone or in combination, may cause an arousal or orgasmic disorder:

♦ certain drugs, including central nervous system depressants, alcohol, street drugs and, rarely, hormonal contraceptives

Abnormal premenopausal bleeding

Causes of abnormal premenopausal bleeding vary with the type of bleeding:

♦ Cryptomenorrhea (no external bleeding, although menstrual symptoms are experienced) may result from an imperforate hymen or cervical stenosis.

♦ Hypermenorrhea (excessive bleeding occurring at regular intervals) usually results from local lesions, such as uterine leiomyomas, endometrial polyps, and endometrial hyperplasia. It may also result from endometritis, salpingitis, or anovulation.

♦ Hypomenorrhea (decreased amount of menstrual fluid) results from local, endocrine, or systemic disorders or blockage caused by partial obstruction by the hymen or cervical obstruction.

♦ Metrorrhagia (bleeding occurring at irregular intervals) usually results from slight physiologic bleeding from the endometrium during ovulation but may also result from local disorders, such as uterine malignancy, cervical erosions, polyps (which tend to bleed after intercourse), or inappropriate estrogen therapy.

♦ Oligomenorrhea (infrequent menses) and polymenorrhea (menses occurring too frequently) usually result from anovulation due to an endocrine or systemic disorder.

Complications of pregnancy can also cause premenopausal bleeding, which may be as mild as spotting or as severe as hypermenorrhea.

♦ general systemic illnesses, diseases of the endocrine or nervous system, or diseases that impair muscle tone or contractility

♦ gynecologic factors, such as chronic vaginal or pelvic infection or pain, congenital anomalies, and genital cancer

♦ inadequate or ineffective stimulation

♦ psychological factors, such as performance anxiety, early traumatic sexual experiences, guilt, depression, or unconscious conflicts about sexuality

♦ relationship problems, such as poor communication, hostility, interpersonal disharmony, or ambivalence toward the partner, fear of abandonment or independence, or boredom with sex

♦ stress and fatigue.

All of these factors may contribute to involuntary inhibition of the orgasmic reflex. Another crucial factor is the fear of losing control of

feelings or behavior. Whether these factors produce sexual dysfunction—as well as the type of dysfunction they produce—depends on how well the woman copes with the resulting pressures. Physical factors may also cause arousal or orgasmic disorder.

feelings or behavior. Whether these factors produce sexual dysfunction—as well as the type of dysfunction they produce—depends on how well the woman copes with the resulting pressures. Physical factors may also cause arousal or orgasmic disorder.

Female sexual function and responses decline, along with estrogen levels, in the perimenopausal period. The decrease in estradiol levels during menopause affects nerve transmission and response in the peripheral vascular system. As a result, the timing and degree of vasoconstriction during the sexual response is affected, vasocongestion decreases, muscle tension decreases, lubrication decreases, and contractions are fewer and less intense during orgasm.

A female with arousal disorder has limited or absent sexual desire and experiences little or no pleasure from sexual stimulation. Physical signs of this disorder include lack of vaginal lubrication or absence of signs of genital vasocongestion. Dyspareunia is genital pain associated with intercourse. Insufficient lubrication is the most common cause. Other physical causes of dyspareunia include:

♦ disorders of the surrounding viscera (including residual effects of pelvic inflammatory disease or disease of the adnexal and broad ligaments)

♦ endometriosis

♦ genital, rectal, or pelvic scar tissue

♦ infections of the genitourinary tract (acute or chronic).

Other possible physical causes include:

♦ allergic reactions to diaphragms, condoms, or other contraceptives

♦ benign and malignant growths and tumors

♦ deformities or lesions of the introitus or vagina

♦ intact hymen

♦ radiation to the pelvis.

Psychological causes include:

♦ anxiety caused by a new sexual partner or technique

♦ fear of pain or injury during intercourse

♦ fear of pregnancy or injury to the fetus during pregnancy

♦ guilty feelings about sex

♦ mental or physical fatigue

♦ previous painful experience, including sexual abuse.

Vaginismus is an involuntary spastic constriction of the lower vaginal muscles, usually from fear of vaginal penetration. This disorder may coexist with dyspareunia and, if severe, may prevent intercourse (a common cause of unconsummated marriages). Vaginismus may be physical or psychological in origin. It may occur spontaneously as a protective reflex to pain or result from organic causes, such as hymenal abnormalities, genital herpes, obstetric trauma, and atrophic vaginitis.

Psychological causes may include:

♦ childhood and adolescent exposure to rigid, punitive, and guilt-ridden attitudes toward sex

♦ early traumatic experience with pelvic examinations

♦ fear of pregnancy, sexually transmitted disease, or cancer

♦ fear resulting from painful or traumatic sexual experiences, such as incest or rape.

In males, the normal sexual response involves erection, emission, and ejaculation. Sexual dysfunction is the impairment of one or all of these processes.

Erectile disorder, or impotence, refers to inability to attain or maintain penile erection sufficient to complete intercourse. Transient periods of impotence aren’t considered dysfunction and probably occur in half the adult males. Erectile disorder affects all age-groups but increases in frequency with age.

With aging, males experience a gradual decline in their serum total and free testosterone levels. This decline may affect both the male libido and sexual function.

With aging, males experience a gradual decline in their serum total and free testosterone levels. This decline may affect both the male libido and sexual function.Psychogenic factors (guilt, fear, depression) are responsible for 50% to 60% of the cases of erectile dysfunction; organic factors, for the rest. In some patients, psychogenic and organic factors (chronic disease, paralysis, consequence of a surgical procedure) coexist, making isolation of the primary cause difficult.

Most problems with emission and ejaculation usually have structural causes.

MALE STRUCTURAL ALTERATIONS

Structural defects of the male reproductive system may be congenital or acquired. Testicular disorders, such as cryptorchidism or torsion, may result in infertility.

In cryptorchidism, a congenital disorder, one or both testes fail to descend into the scrotum, remaining in the abdomen or inguinal canal or at the external ring. If bilateral cryptorchidism persists untreated into adolescence, it may result in sterility, make the testes more vulnerable to trauma, and significantly increase the risk for testicular cancer, particularly germ cell tumors. It should be corrected between the ages of 12 and 24 months to reduce the risk of male infertility. In about 75% of affected infants, the testes descend spontaneously during the

first year; in the rest, the testes may descend through puberty.

first year; in the rest, the testes may descend through puberty.

The testes of an older male may be slightly smaller than those of a younger male, but they should be equal in size, smooth, freely moveable, and soft, without nodules. The left testis is commonly lower than the right.

The testes of an older male may be slightly smaller than those of a younger male, but they should be equal in size, smooth, freely moveable, and soft, without nodules. The left testis is commonly lower than the right.Benign prostatic hyperplasia is a disorder of prostate enlargement due to androgen-induced growth of prostate cells. It’s more prevalent with aging and may result in urinary obstructive symptoms.

Hypospadias is the most common penile structural abnormality. The midline fusion of the urethral folds is incomplete, so the urethral meatus opens on the ventral (anterior, or “belly”) surface of the penis. In epispadias, the urethral meatus is located on the dorsal (posterior, or “back”) surface of the penis.

Priapism is prolonged, painful erection in the absence of sexual stimulation. It results from arteriovenous shunting within the corpus cavernosum that leads to obstructed venous outflow from the penis. The most common cause is drug therapy for erectile dysfunction. It’s also associated with the use of antihypertensives, anticoagulants, cocaine, corticosteroids, and amphetamines. In children it may be associated with sickle cell disease, leukemia, blood clots, or pelvic tumors. Without prompt treatment it can lead to ischemic fibrosis and infertility.

A urethral stricture is a narrowing of the urethra caused by scarring. It may result from trauma, surgery (adhesions), or infection. Common complications include prostatitis and secondary infection.

During the first 3 years of life, congenital adhesions between the foreskin and the glans penis separate naturally with penile erections. Phimosis is a condition in which the foreskin can’t be retracted over the glans penis; it can be congenital or acquired (from forceful retraction) or can result from poor hygiene or chronic infection. Paraphimosis is a condition in which the foreskin is retracted behind the coronal sulcus; the penis becomes constricted, causing edema of the glans. Severe paraphimosis is a surgical emergency.

To prevent threatened spontaneous abortion, millions of women took diethylstilbestrol (DES) between 1946 and 1971. Men whose mothers took DES during their 8th to 16th weeks of pregnancy experienced structural abnormalities, such as urethral meatal stenosis, hypospadias, epididymal cysts, varicoceles, cryptorchidism, and decreased fertility.

Disorders

Disorders of the reproductive system may affect sexual, reproductive, or urinary function. Reproductive system disorders include abnormal uterine bleeding, amenorrhea, benign prostatic hyperplasia, cryptorchidism, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, erectile dysfunction, gynecomastia, hydrocele, ovarian cysts, polycystic ovarian syndrome, premenstrual syndrome, precocious puberty, prostatitis, testicular torsion, uterine fibroids, and varicocele.

ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

Abnormal uterine bleeding refers to abnormal endometrial bleeding without recognizable organic lesions. Abnormal uterine bleeding is the indication for almost 25% of gynecologic surgical procedures. The prognosis varies with the cause. Correction of hormonal imbalance or structural abnormality yields a good prognosis.

Causes

Abnormal uterine bleeding usually results from an imbalance in the hormonal-endometrial relationship in which persistent and unopposed stimulation of the endometrium by estrogen occurs. Before menarche, it may also result from malignancy, trauma, or sexual abuse.

Disorders that cause sustained a high estrogen level include:

♦ anovulation (women in their late 30s to early 40s)

♦ immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitaryovarian mechanism (postpubertal teenagers)

♦ obesity (because enzymes present in peripheral adipose tissue convert the androgen androstenedione to estrogen precursors)

♦ polycystic ovary syndrome.

Other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding include:

♦ coagulopathy, such as thrombocytopenia or leukemia (rare)

♦ drug-induced coagulopathy, adrenal hyperplasia, or Cushing’s disease

♦ endometriosis

♦ genital tract infections, neoplasms, or other pathology

♦ liver, renal, or thyroid disease

♦ medications and iatrogenic causes

♦ trauma (foreign object insertion or direct trauma)

♦ von Willebrand’s disease.

Pathophysiology

Irregular bleeding is associated with hormonal imbalance and anovulation (failure of ovulation to occur). When progesterone secretion is

absent but estrogen secretion continues, the endometrium proliferates and becomes hypervascular. When ovulation doesn’t occur, the endometrium is randomly broken down, and exposed vascular channels cause prolonged, excessive bleeding. In most cases of abnormal uterine bleeding, the endometrium shows no pathologic changes. However, in chronic unopposed estrogen stimulation (as from a hormoneproducing ovarian tumor), the endometrium may show hyperplastic or malignant changes.

absent but estrogen secretion continues, the endometrium proliferates and becomes hypervascular. When ovulation doesn’t occur, the endometrium is randomly broken down, and exposed vascular channels cause prolonged, excessive bleeding. In most cases of abnormal uterine bleeding, the endometrium shows no pathologic changes. However, in chronic unopposed estrogen stimulation (as from a hormoneproducing ovarian tumor), the endometrium may show hyperplastic or malignant changes.

Signs and symptoms

♦ Metrorrhagia (episodes of vaginal bleeding between menses)

♦ Hypermenorrhea (heavy or prolonged menses, longer than 8 days)

♦ Chronic polymenorrhea (menstrual cycle less than 18 days) or oligomenorrhea (infrequent menses)

♦ Fatigue due to anemia

♦ Oligomenorrhea and infertility due to anovulation

♦ Postcoital bleeding

♦ Pelvic pain

♦ Weight changes

Complications

♦ Iron-deficiency anemia (blood loss of more than 1.6 L over a short time) and hemorrhagic shock or right-sided heart failure (rare)

♦ Endometrial adenocarcinoma due to chronic estrogen stimulation

Diagnosis

Abnormal uterine bleeding may be caused by anovulation. Diagnosis of anovulation is based on:

♦ history of abnormal bleeding, bleeding in response to a brief course of progesterone, absence of ovulatory cycle body temperature changes, and a low serum progesterone level (A “bleeding calendar” may be helpful to define the pattern of bleeding and to record the number of pads and tampons used.)

♦ diagnostic studies ruling out other causes of excessive vaginal bleeding, such as organic, systemic, psychogenic, and endocrine causes, including certain cancers, polyps, pregnancy, and infection

♦ dilatation and curettage (D&C) or endometrial biopsy to rule out endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in women older than age 35

♦ imaging studies, such as transvaginal ultrasonography to determine endometrial thickness and sonohysterography to evaluate the endometrial cavity and identify structural problems

♦ hemoglobin level and hematocrit to determine the need for blood transfusion or iron supplementation.

Treatment

♦ High-dose estrogen-progestogen combination therapy (a hormonal contraceptive) to control endometrial growth and reestablish a normal cyclic pattern of menstruation; maintenance therapy with lower-dose combination hormonal contraceptives

♦ Endometrial biopsy to rule out endometrial adenocarcinoma (patients age 35 and older)

♦ Progestogen therapy (alternative in many women, such as those susceptible to such adverse effects of estrogen as thrombophlebitis)

♦ I.V. estrogen followed by progesterone or combination hormonal contraceptives if the patient is young (more likely to be anovulatory) and severely anemic (if oral drug therapy is ineffective)

♦ D&C (short-lived treatment and not clinically useful, but an important diagnostic tool) with hysteroscopy as a useful adjunct

♦ Iron supplementation or transfusions of packed cells or whole blood, as indicated, due to anemia caused by recurrent or excessive bleeding

♦ Explaining the importance of following the prescribed hormonal therapy; explaining D&C or endometrial biopsy procedure and purpose (if ordered)

♦ Stressing the need for regular checkups to assess the effectiveness of treatment

Special considerations

♦ If a patient complains of abnormal bleeding, tell her to record the dates of the bleeding and the number of sanitary pads she saturates per day. This helps in assessing the pattern and the amount of bleeding. Instruct the patient not to use tampons.

♦ Instruct the patient to immediately report abnormal bleeding to help rule out major hemorrhagic disorders, such as those that occur in abnormal pregnancy.

♦ To prevent abnormal bleeding due to organic causes and to ensure early detection of malignancy, encourage the patient to have a Papanicolaou test and a pelvic examination annually.

AMENORRHEA

Amenorrhea is the abnormal absence or suppression of menstruation. Absence of menstruation is normal before puberty, after menopause, or during pregnancy and lactation; it’s abnormal— and therefore pathologic—at any other time. Primary amenorrhea is the absence of menarche in an adolescent (age 16 and older). Secondary amenorrhea is the failure of menstruation for at least 3 cycle intervals or 6 months after the normal onset of menarche. Primary amenorrhea occurs in 0.3% of women; secondary amenorrhea is seen in 1% to 3% of women. Prognosis varies, depending on the specific cause. Surgical correction of outflow tract obstruction is usually curative.

Causes

Amenorrhea usually results from:

♦ anovulation due to hormonal abnormalities, such as decreased secretion of estrogen, folliclestimulating hormone (FSH), gonadotropins, and luteinizing hormone

♦ constant presence of progesterone or other endocrine abnormalities

♦ lack of ovarian response to gonadotropins.

Amenorrhea may also result from:

♦ absence of a uterus, cervix, or vagina, or of more than one of these structures

♦ adrenal, ovarian, or pituitary tumors

♦ emotional disorders (common in patients with severe disorders, such as depression and anorexia nervosa); mild emotional disturbances tending to distort the ovulatory cycle; severe psychic trauma abruptly changing the bleeding pattern or completely suppressing one or more full ovulatory cycles

♦ endometrial damage

♦ malnutrition and intense exercise, causing an inadequate hypothalamic response

♦ systemic disorders, such as hypothyroidism or pituitary disease

♦ a transverse vaginal septum or imperforate hymen.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism varies depending on the cause and whether the defect is structural, hormonal, or both. Women who have an adequate estrogen level but a progesterone deficiency don’t ovulate and are thus infertile. In primary amenorrhea, the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis is dysfunctional. Because of anatomic defects of the central nervous system, the ovary doesn’t receive the hormonal signals that normally initiate the development of secondary sex characteristics and the beginning of menstruation.

Secondary amenorrhea can result from several central factors (hypogonadotropic hypoestrogenic anovulation), uterine factors (as with Asherman syndrome, in which the endometrium is sufficiently scarred that no functional endometrium exists), cervical stenosis, premature ovarian failure, and others.

Signs and symptoms

Amenorrhea may result from many disorders. Signs and symptoms depend on the specific cause, and include:

♦ absence of menstruation

♦ vasomotor flushes, vaginal atrophy, hirsutism (abnormal hairiness), and acne (secondary amenorrhea).

Complications

♦ Infertility

♦ Osteoporosis (associated with long-term amenorrhea)

♦ Endometrial adenocarcinoma (amenorrhea associated with anovulation that gives rise to unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium)

Diagnosis

♦ History of failure to menstruate in females age 16 and older, if consistent with bone age confirms primary amenorrhea.

♦ Absence of menstruation for 3 cycle intervals or 6 months in a previously established menstrual pattern confirms secondary amenorrhea.

♦ Breast development absence or presence is a marker of estrogen action and function of the ovary.

♦ Physical and pelvic examination and sensitive pregnancy test rule out pregnancy, as well as anatomic abnormalities (such as cervical stenosis) that may cause false amenorrhea (cryptomenorrhea), in which menstruation occurs without external bleeding.

♦ Onset of menstruation (spotting) within 1 week after giving pure progestational agents, such as medroxyprogesterone (Provera), indicates that there’s enough estrogen to stimulate the lining of the uterus. If menstruation doesn’t occur, special diagnostic studies, such as gonadotropin levels, are indicated.

♦ Blood and urine studies show hormonal imbalances, such as lack of ovarian response to gonadotropins (an elevated pituitary gonadotropin level), failure of gonadotropin secretion (a low pituitary gonadotropin level), and abnormal thyroid levels. Without suspicion of premature

ovarian failure or central hypogonadotropism, gonadotropin levels aren’t clinically meaningful because they’re released in a pulsatile fashion; at a given time of day, levels may be elevated, low, or average.

ovarian failure or central hypogonadotropism, gonadotropin levels aren’t clinically meaningful because they’re released in a pulsatile fashion; at a given time of day, levels may be elevated, low, or average.

♦ Complete medical workup, including pelvic ultrasound, appropriate X-rays, laparoscopy, and a biopsy, identify ovarian, adrenal, and pituitary tumors.

Tests to identify dominant or missing hormones include:

♦ “ferning” of cervical mucus on microscopic examination (an estrogen effect)

♦ vaginal cytologic examination

♦ endometrial biopsy

♦ low serum progesterone level

♦ high serum androgen level

♦ an elevated urinary 17-ketosteroid level with excessive androgen secretions

♦ a plasma FSH level more than 50 IU/L, depending on the laboratory (suggests primary ovarian failure); or normal or low FSH level (possible hypothalamic or pituitary abnormality, depending on the clinical situation).

Treatment

♦ Appropriate hormone replacement to reestablish menstruation

♦ Treatment of the cause of amenorrhea not related to hormone deficiency (for example, surgery for amenorrhea due to a tumor or obstruction)

♦ Inducing ovulation; with intact pituitary gland, clomiphene citrate (Clomid) may induce ovulation in women with secondary amenorrhea due to gonadotropin deficiency, polycystic ovarian disease, or excessive weight loss or gain if it’s reversed

♦ FSH and human menopausal gonadotropins (Pergonal) for women with pituitary disease

♦ Improving nutritional status

♦ Modification of exercise routine

Special considerations

♦ Explain all diagnostic procedures to the patient.

♦ Provide reassurance and emotional support. Psychiatric counseling may be necessary if amenorrhea results from emotional disturbances.

♦ After treatment, teach the patient how to keep an accurate record of her menstrual cycles to aid early detection of recurrent amenorrhea.

BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA

Although most men age 50 and older have some prostatic enlargement, in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)—also known as benign prostatic hypertrophy or nodular hyperplasia—the prostate gland enlarges enough to compress the urethra and cause overt urinary obstruction. (See Prostatic enlargement.) Depending on the size of the enlarged prostate, the age and health of the patient, and the extent of obstruction, BPH is treated symptomatically or surgically. BPH is common, affecting 40% to 50% of men ages 50 to 60, and more than 80% of men age 80 and older. It also affects about 8% of men ages 31 to 40.

Causes

The main cause of BPH may be age-associated changes in hormone activity. Androgenic hormone production decreases with age, causing imbalance in androgen and estrogen levels and a high level of dihydrotestosterone, the main prostatic intracellular androgen. A genetic predisposition (most likely an autosomal dominant trait) may be responsible for 10% of cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree