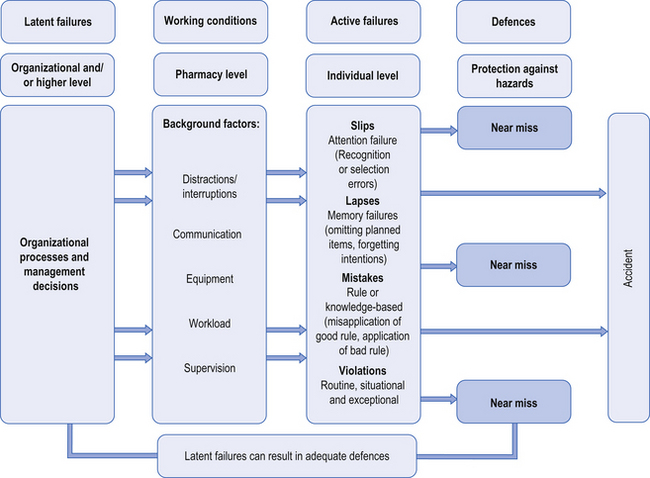

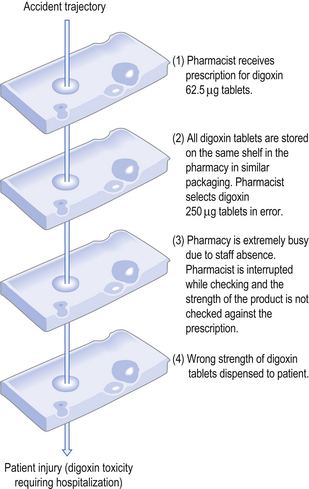

10 Risk – the probability that an adverse event will occur – is a normal part of daily life. We all continuously face risks and make decisions about them. Each day we decide when it is safe to cross the road and when it is more sensible to wait; we may choose to travel by car rather than walk. In these everyday choices, we assess the potential risks and benefits, and select a plan of action. Risk management is all about this process of anticipating potential hazards and reducing the likelihood of a problem occurring. However, before thinking about how to minimize or eliminate the possibility of errors, it is important to first consider how errors occur. During the past decade, there has been increased interest to understand how management practices and other workplace factors impact on patient safety. The systems approach acknowledges that humans are imperfect and errors are to be expected, even in the best organizations. Rather than focusing on the individual, the systems approach concentrates on the conditions under which individuals work, trying to build defences to avoid errors or to mitigate their effects. James Reason (2000) classified medical errors into two types, active and latent failures, where active failures are unsafe acts (e.g. dispensing the wrong drug) committed by individuals who are at the ‘sharp end’ of health care, while latent failures are more distant from the actual incident and reflect failures in management or other organizational factors. Active failures take a variety of forms, such as slips, lapses, mistakes and procedural violations, as shown in Figure 10.1. Slips occur when there has been a lack of attention, despite the fact that the individual has all the necessary skills to complete the task successfully. Lapses involve memory failures, such as forgetting your intentions or omitting planned actions. In contrast, mistakes happen when we are in conscious control of the situation, but successfully execute the wrong plan of action. For instance, selecting the wrong plan can come about because of an incorrect assessment of the situation, such as arriving at the wrong diagnosis for an individual asking for an effective treatment for an ‘upset stomach’. Violations, on the other hand, involve deliberate deviations from the procedures or best way of performing a task, such as not following SOPs (see Ch. 11) within the pharmacy. Several types of violations have been described, which are outlined in Box 10.1. Each of these error types (slips, lapses, mistakes, violations) requires different strategies to be implemented to avoid similar events occurring in the future. Better system defences, such as redesigning the workplace, can help to minimize slips and lapses. Improved training and rigorous checking procedures can prevent some mistakes. Developing relevant procedures and protocols, ensuring effective implementation with the provision of the necessary resources and support are all important in promoting compliance and therefore avoiding procedural violations. The investigation of many threats to patient safety has shown that there are usually multiple causes and they tend to occur when there is an unfortunate combination of active and latent failures. Reason (2000) proposed the ‘Swiss cheese’ model to illustrate how accidents can occur within systems. This analogy compares the defensive layers of the system to layers of Swiss cheese, each having holes that represent safety failures. The presence of holes in one slice may not result in an accident because the other slices act as safeguards. However, the holes in the layers may temporarily line-up, creating an opportunity for an accident. Figure 10.2 shows how multiple failures in the pharmacy setting can result in patient harm.

Risk management

The use of human error models to understand the causes of patient safety incidents

The use of human error models to understand the causes of patient safety incidents

Risk management techniques that can be used to understand the ‘root causes’ of an incident

Risk management techniques that can be used to understand the ‘root causes’ of an incident

Some of the common risks in the pharmacy setting

Some of the common risks in the pharmacy setting

The National Patient Safety Agency’s ‘Seven Steps to Patient Safety’

The National Patient Safety Agency’s ‘Seven Steps to Patient Safety’

A structured approach to undertaking risk assessment in the pharmacy

A structured approach to undertaking risk assessment in the pharmacy

Introduction

Human error models

Active failures

Latent failures

Risk management tools

Mapping out the steps of the process through group discussion

Mapping out the steps of the process through group discussion

Identification of possible failure modes (what could go wrong?) by brainstorming

Identification of possible failure modes (what could go wrong?) by brainstorming

For each error type or failure mode identified, a cause (why should failure happen?) and effect (what would be the consequences of each failure?) are attributed, together with scores for likelihood of occurrence, likelihood of detection and severity.

For each error type or failure mode identified, a cause (why should failure happen?) and effect (what would be the consequences of each failure?) are attributed, together with scores for likelihood of occurrence, likelihood of detection and severity.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree