26

Rickettsiae

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Rickettsiae are obligate intracellular bacteria; that is, they can grow only within cells. They are the agents of typhus, spotted fevers, and Q fever.

Diseases

In the United States, there are two rickettsial diseases of significance: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, and Q fever, caused by Coxiella burnetii. Epidemic typhus, caused by Rickettsia prowazekii, is an important disease that occurs mainly in crowded, unsanitary living conditions during wartime. Other rickettsial diseases such as endemic and scrub typhus occur primarily in developing countries. Rickettsialpox, caused by Rickettsia akari, is a rare disease found in certain densely populated cities in the United States. Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum are described in Chapter 27.

Important Properties

Rickettsiae are very short rods that are barely visible in the light microscope. Structurally, their cell wall resembles that of gram-negative rods, but they stain poorly with the standard Gram stain.

Rickettsiae are obligate intracellular parasites, because they are unable to produce sufficient energy to replicate extracellularly. Therefore, rickettsiae must be grown in cell culture, embryonated eggs, or experimental animals. Rickettsiae divide by binary fission within the host cell, in contrast to chlamydiae, which are also obligate intracellular parasites but replicate by a distinctive intracellular cycle.

Several rickettsiae, such as Rickettsia prowazekii, Rickettsia tsutsugamushi, and R. rickettsii, possess antigens that cross-react with antigens of the OX strains of Proteus vulgaris. The Weil-Felix test, which detects antirickettsial antibodies in a patient’s serum by agglutination of the Proteus organisms, is based on this cross-reaction.

C. burnetii has a sporelike stage that is highly resistant to drying, which enhances its ability to cause infection. It also has a very low ID50 estimated to be approximately one organism. C. burnetii exists in two phases that differ in their antigenicity and their virulence: phase I organisms are isolated from the patient, are virulent, and synthesize certain surface antigens, whereas phase II organisms are produced by repeated passage in culture, are nonvirulent, and have lost the ability to synthesize certain surface antigens. The clinical importance of phase variation is that patients with chronic Q fever have a much higher antibody titer to phase I antigens than those with acute Q fever.

Transmission

The most striking aspect of the life cycle of the rickettsiae is that they are maintained in nature in certain arthropods such as ticks, lice, fleas, and mites and, with one exception, are transmitted to humans by the bite of the arthropod. The rickettsiae circulate widely in the bloodstream (bacteremia), infecting primarily the endothelium of the blood vessel walls.

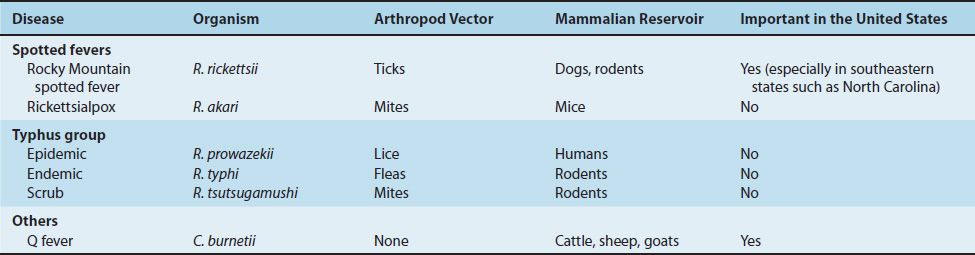

The exception to arthropod transmission is C. burnetii, the cause of Q fever, which is transmitted by aerosol and inhaled into the lungs. Virtually all rickettsial diseases are zoonoses (i.e., they have an animal reservoir), with the prominent exception of epidemic typhus, which occurs only in humans. It occurs only in humans because the causative organism, R. prowazekii, is transmitted by the human body louse. A summary of the vectors and reservoirs for selected rickettsial diseases is presented in Table 26–1.

The incidence of the disease depends on the geographic distribution of the arthropod vector and on the risk of exposure, which is enhanced by such things as poor hygienic conditions and camping in wooded areas. These factors are discussed later with the individual diseases.

Pathogenesis

The typical lesion caused by the rickettsiae is a vasculitis, particularly in the endothelial lining of the vessel wall where the organism is found. Damage to the vessels of the skin results in the characteristic rash and in edema and hemorrhage caused by increased capillary permeability. The basis for pathogenesis by these organisms is unclear. There is some evidence that endotoxin is involved, which is in accord with the nature of some of the lesions such as fever and petechiae, but its role has not been confirmed. No exotoxins or cytolytic enzymes have been found.

Clinical Findings & Epidemiology

This section is limited to the two rickettsial diseases that are most common in the United States (i.e., Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Q fever) and to the other major rickettsial disease, typhus.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

This disease is characterized by the acute onset of nonspecific symptoms (e.g., fever, severe headache, myalgias, and prostration). The typical rash, which appears 2 to 6 days later, begins with macules that frequently progress to petechiae (Figure 26–1). The rash usually appears first on the hands and feet and then moves inward to the trunk. In addition to headache, other profound central nervous system changes such as delirium and coma can occur. Disseminated intravascular coagulation, edema, and circulatory collapse may ensue in severe cases. The diagnosis must be made on clinical grounds and therapy started promptly, because the laboratory diagnosis is delayed until a rise in antibody titer can be observed.

FIGURE 26–1 Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Note widespread petechial rash. (Reproduced from MMWR, Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Ehrlichiosis, and Anaplasmosis–United States. March 13, 2006/55(RR04);1–27, http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree