Chapter 11 Rheumatology and bone disease

Rheumatological and musculoskeletal disorders

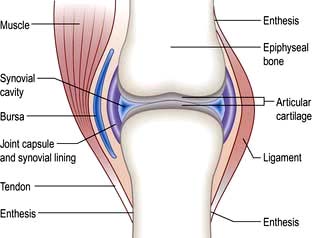

The normal joint

There are three types of joints: fibrous, fibrocartilaginous and synovial.

Synovial joints

These (Fig. 11.1) include the ball-and-socket joints (e.g. hip) and the hinge joints (e.g. interphalangeal).

Juxta-articular bone

The bone which abuts a joint (epiphyseal bone) differs structurally from the shaft (metaphysis) (see Fig. 11.32). It is highly vascular and comprises a light framework of mineralized collagen enclosed in a thin coating of tougher, cortical bone. The ability of this structure to withstand pressure is low and it collapses and fractures when the normal intra-articular covering of hyaline cartilage is worn away as in osteoarthritis (OA; see p. 512). Loss of surface cartilage also leads to the abnormalities of bone growth and remodelling typical of OA (see p. 512).

Ligaments and tendons

These structures stabilize joints. Ligaments are variably elastic and this contributes to the stiffness or laxity of joints (see p. 559). Tendons are inelastic and transmit muscle power to bones. The joint capsule is formed by intermeshing tendons and ligaments. The point where a tendon or ligament joins a bone is called an enthesis and may be the site of inflammation.

Components of extracellular matrix

Collagens. Collagens consist of three polypeptide (α) chains wound into a triple helix. These alpha chains contain repeating sequences of Gly-x-y triplets, where x and y are often prolyl and hydroxypropyl residues. Collagen fibres show genetic heterogeneity, with genes on at least 12 chromosomes. Hyaline cartilage is 90% type II (COL2A1). There are several classes of collagen genes, based on their protein structures, and abnormalities of these may lead to specific diseases (see p. 560).

Skeletal muscle

This consists of bundles of myocytes containing actin and myosin molecules. These molecules interdigitate and form myofibrils which cause muscle contraction in a similar way to myocardial muscle (p. 671). Bundles of myofibrils (fasciculi) are covered by connective tissue, the perimysium, which merges with the epimysium (covering the muscle) and forms the tendon which attaches to the bone surface (enthesis).

Clinical approach to the patient

Taking a musculoskeletal history

Where is it? Is it localized or generalized? The pattern of joint involvement is a useful clue to the diagnosis (e.g. distal interphalangeal joints in nodal osteoarthritis).

Where is it? Is it localized or generalized? The pattern of joint involvement is a useful clue to the diagnosis (e.g. distal interphalangeal joints in nodal osteoarthritis).

Is it arising from joints, the spine, muscles or bone, with local tenderness? Soft tissue lesions and inflamed joints are locally tender.

Is it arising from joints, the spine, muscles or bone, with local tenderness? Soft tissue lesions and inflamed joints are locally tender.

Could it be referred from another site? Joint pain is localized but may radiate distally – shoulder to upper arm; hip to thigh and knee.

Could it be referred from another site? Joint pain is localized but may radiate distally – shoulder to upper arm; hip to thigh and knee.

Is it constant, intermittent or episodic? How severe is it – aching or agonizing?

Is it constant, intermittent or episodic? How severe is it – aching or agonizing?

Are there aggravating or precipitating factors? Is it made worse by activity and eased by rest (mechanical) or worse after rest (inflammatory).

Are there aggravating or precipitating factors? Is it made worse by activity and eased by rest (mechanical) or worse after rest (inflammatory).

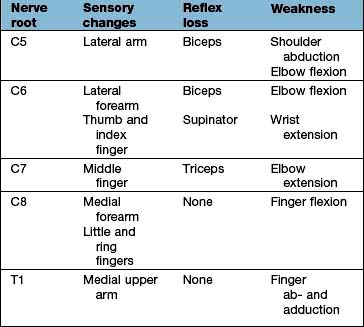

Are there any associated neurological features? Numbness, pins and needles and/or loss of power suggest ‘nerve’ involvement. The distribution of symptoms is a useful clue to the nerve or nerve root affected.

Are there any associated neurological features? Numbness, pins and needles and/or loss of power suggest ‘nerve’ involvement. The distribution of symptoms is a useful clue to the nerve or nerve root affected.

Gout (see p. 530), reactive arthritis (p. 529) and ankylosing spondylitis (p. 527) are more common in men. Rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune rheumatic diseases are more common in women.

Is the person young, middle-aged or older?

Is the person young, middle-aged or older?

How old was the patient when the problem first started? Osteoarthritis (see p. 512) and polymyalgia rheumatica (p. 542) rarely affect the under-50s. Rheumatoid arthritis starts most commonly in women aged 30–50 years.

How old was the patient when the problem first started? Osteoarthritis (see p. 512) and polymyalgia rheumatica (p. 542) rarely affect the under-50s. Rheumatoid arthritis starts most commonly in women aged 30–50 years.

Is there any associated ill-health or other worrying feature, such as weight loss or fever?

Is there any associated ill-health or other worrying feature, such as weight loss or fever?

Are there other associated medical conditions that may be relevant? Psoriasis (see p. 1207) or inflammatory bowel disease is associated with spondyloarthritis (see p. 1004). Charcot’s joints (p. 547) are seen in diabetics.

Are there other associated medical conditions that may be relevant? Psoriasis (see p. 1207) or inflammatory bowel disease is associated with spondyloarthritis (see p. 1004). Charcot’s joints (p. 547) are seen in diabetics.

Could a drug be a cause? Diuretics may precipitate gout in men and older women. Hormone replacement therapy or the oral contraceptive pill may precipitate systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (p. 535). Steroids can cause avascular necrosis. Some drugs cause a lupus-like syndrome (p. 535).

Is this relevant? Sickle cell disease causes joint pain in young black Africans, but osteoporosis (see p. 552) is uncommon in older black Africans.

Have there been any similar episodes or is this the first? Are there any clues from previous medical conditions? Gout is recurrent; the episodes settle without treatment in 7–10 days. Acute episodes of palindromic rheumatism may predate the onset of rheumatoid arthritis (see p. 519).

The biopsychosocial model of disease is highly relevant to many rheumatic disorders:

Has there been any recent major stress in family or working life? Could this be relevant? Stress rarely causes rheumatic disease but may precipitate a flare-up of inflammatory arthritis. It reduces a person’s ability to cope with pain or disability.

Has there been any recent major stress in family or working life? Could this be relevant? Stress rarely causes rheumatic disease but may precipitate a flare-up of inflammatory arthritis. It reduces a person’s ability to cope with pain or disability.

Has there been an injury for which a legal case for compensation is pending?

Has there been an injury for which a legal case for compensation is pending?

The World Health Organization describes the impact of disease on an individual in terms of:

Impairment: any loss or abnormality of psychological or anatomical structure or function

Impairment: any loss or abnormality of psychological or anatomical structure or function

Disability (activity limitation): any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being

Disability (activity limitation): any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being

Handicap (participation restriction): a disadvantage for an individual resulting from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal for that individual.

Handicap (participation restriction): a disadvantage for an individual resulting from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal for that individual.

Examination of the joints

Always observe a patient, looking for disabilities, as he or she walks into the room and sits down. General and neurological examinations are often necessary. Guidelines for rapid examinations of the limbs and spine are shown in Practical Box 11.1.

![]() Practical Box 11.1

Practical Box 11.1

Rapid examinations of the limb and spine

Rapid examination of the upper limbs

Raise arms sideways to the ears (abduction). Reach behind neck and back. Difficulties with these movements indicate a shoulder or rotator cuff problem.

Raise arms sideways to the ears (abduction). Reach behind neck and back. Difficulties with these movements indicate a shoulder or rotator cuff problem.

Hold the arms forward, with elbows straight and fingers apart, palm up and palm down. Fixed flexion at the elbow indicates an elbow problem. Examine the hands for swelling, wasting and deformity.

Hold the arms forward, with elbows straight and fingers apart, palm up and palm down. Fixed flexion at the elbow indicates an elbow problem. Examine the hands for swelling, wasting and deformity.

Place the hands in the ‘prayer’ position with the elbows apart. Flexion deformities of the fingers may be due to arthritis, flexor tenosynovitis or skin disease. Painful restriction of the wrist limits the person’s ability to move the elbows out with the hands held together.

Place the hands in the ‘prayer’ position with the elbows apart. Flexion deformities of the fingers may be due to arthritis, flexor tenosynovitis or skin disease. Painful restriction of the wrist limits the person’s ability to move the elbows out with the hands held together.

Make a tight fist. Difficulty with this indicates a loss of flexion or grip. Grip strength can be measured.

Make a tight fist. Difficulty with this indicates a loss of flexion or grip. Grip strength can be measured.

Rapid examination of the lower limbs

Ask the patient to walk a short distance away from and towards you, and to stand still. Look for abnormal posture or stance.

Ask the patient to walk a short distance away from and towards you, and to stand still. Look for abnormal posture or stance.

Ask the patient to stand on each leg. Severe hip disease causes the pelvis on the non-weight-bearing side to sag (positive Trendelenburg test).

Ask the patient to stand on each leg. Severe hip disease causes the pelvis on the non-weight-bearing side to sag (positive Trendelenburg test).

Watch the patient stand and sit, looking for hip and/or knee problems.

Watch the patient stand and sit, looking for hip and/or knee problems.

Ask the patient to straighten and flex each knee.

Ask the patient to straighten and flex each knee.

Ask the patient to place each foot in turn on the opposite knee with the hip externally rotated. This tests for painful restriction of hip or knee. Abnormal hips or knees must be examined lying.

Ask the patient to place each foot in turn on the opposite knee with the hip externally rotated. This tests for painful restriction of hip or knee. Abnormal hips or knees must be examined lying.

Move each ankle up and down. Examine the ankle joint and tendons, medial arch and toes whilst standing.

Move each ankle up and down. Examine the ankle joint and tendons, medial arch and toes whilst standing.

Rapid examination of the spine

Ask the patient to (a) bend forwards to touch the toes with straight knees, (b) extend backwards, (c) flex sideways, and (d) look over each shoulder, flexing and extending and sideflexing the neck. Observe abnormal spinal curves – scoliosis (lateral curve), kyphosis (forward bending) or lordosis (backward bending). A cervical and lumbar lordosis and a thoracic kyphosis are normal. Muscle spasm is worse whilst standing and bending. Leg length inequality leads to a scoliosis which decreases on sitting or lying (the lengths are measured lying).

Ask the patient to (a) bend forwards to touch the toes with straight knees, (b) extend backwards, (c) flex sideways, and (d) look over each shoulder, flexing and extending and sideflexing the neck. Observe abnormal spinal curves – scoliosis (lateral curve), kyphosis (forward bending) or lordosis (backward bending). A cervical and lumbar lordosis and a thoracic kyphosis are normal. Muscle spasm is worse whilst standing and bending. Leg length inequality leads to a scoliosis which decreases on sitting or lying (the lengths are measured lying).

Ask the patient to lie supine. Examine any restriction of straight-leg raising (see disc prolapse, below).

Ask the patient to lie supine. Examine any restriction of straight-leg raising (see disc prolapse, below).

Ask the patient to lie prone. Examine for anterior thigh pain during a femoral stretch test (flexing knee whilst prone), which indicates a high lumbar disc problem.

Ask the patient to lie prone. Examine for anterior thigh pain during a femoral stretch test (flexing knee whilst prone), which indicates a high lumbar disc problem.

Examining an individual joint involves three stages: looking, feeling and moving (Table 11.1). A screening examination of the locomotor system, known by the acronym GALS (Global Assessment of the Locomotor System) has been devised. X-ray or ultrasound of the joint often forms an integral part of the examination.

Table 11.1 Examination of the joint

LOOK at the appearance of the joint | Swelling – could be bony, fluid or synovial |

Deformity – valgus, where the distal bone is deviated laterally (e.g. knock-knees or genu valgum) | |

Varus where the distal bone is deviated medially (bow-legs or genu varum) | |

Fixed flexion or hyperextension | |

Rash – especially psoriasis | |

Muscle wasting – easier to see in large muscles like the quadriceps | |

Scars – from surgery or trauma | |

Signs of inflammationSymmetry – are the right and left joints (e.g. hips, knees, any other paired joint) the same? If not which do you think is abnormal? | |

FEEL | Swelling – fluid swelling (effusion) usually represents increased synovial fluid in inflammatory arthritis, but can be due to blood or pus |

Synovial swelling is rubbery or boggy and usually occurs in inflammatory arthritis | |

Bony swelling, such as Heberden’s nodes in the fingers is usually seen in osteoarthritis | |

Warmth – a warm joint may be inflamed or infected | |

Tenderness – may represent joint inflammation, but many people have chronic tenderness all over the body (e.g. in fibromyalgia) | |

MOVE | Active movement – is the range full and pain-free? Is the movement fluid? In the hands – can the patient perform fine movements? In the legs – can the patient walk properly? |

Compare movements on the right and left side – are they symmetrical? | |

Is there crepitus when the joint is moved? | |

If active movement is limited try passive movement. In a joint problem both will usually be affected. If it is a muscle or nerve problem passive movement may remain full. |

Investigations

Useful blood screening tests

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). An increase of these reflects inflammation. Plasma viscosity is also raised in inflammatory disease.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). An increase of these reflects inflammation. Plasma viscosity is also raised in inflammatory disease.

Bone and liver biochemistry. A raised serum alkaline phosphatase may indicate liver or bone disease. A rise in liver enzymes is seen with drug-induced toxicity. For other investigations of bone, see page 550.

Bone and liver biochemistry. A raised serum alkaline phosphatase may indicate liver or bone disease. A rise in liver enzymes is seen with drug-induced toxicity. For other investigations of bone, see page 550.

Serum autoantibody studies

Rheumatoid factors (RFs) (see also p. 518). Rheumatoid factors are detected by enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA). RFs are antibodies (usually IgM, but also IgG or IgA) against the Fc portion of IgG. They are detected in 70% of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but are not diagnostic. RFs are detected in many autoimmune rheumatic disorders (e.g. SLE), in chronic infections, and in asymptomatic older people (Table 11.2).

Rheumatoid factors (RFs) (see also p. 518). Rheumatoid factors are detected by enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA). RFs are antibodies (usually IgM, but also IgG or IgA) against the Fc portion of IgG. They are detected in 70% of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but are not diagnostic. RFs are detected in many autoimmune rheumatic disorders (e.g. SLE), in chronic infections, and in asymptomatic older people (Table 11.2).

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA). These antibodies are directed against citrullinated antigens, vimentin, fibrinogen, alpha enolase and type II collagen. They are measured by an ELISA technique and are present in up to 80% of people with RA. They have a high specificity for RA (90% with a sensitivity of 60%). They are helpful in early disease when the RF is negative to distinguish it from acute transient synovitis (see Box 11.6, p. 519). Positivity for RF and/or ACPA is associated with a worse prognosis and an increase in the likelihood of bony erosions in people with RA.

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA). These antibodies are directed against citrullinated antigens, vimentin, fibrinogen, alpha enolase and type II collagen. They are measured by an ELISA technique and are present in up to 80% of people with RA. They have a high specificity for RA (90% with a sensitivity of 60%). They are helpful in early disease when the RF is negative to distinguish it from acute transient synovitis (see Box 11.6, p. 519). Positivity for RF and/or ACPA is associated with a worse prognosis and an increase in the likelihood of bony erosions in people with RA.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). These are detected by indirect immunofluorescent staining of fresh-frozen sections of rat liver or kidney or Hep-2 cell lines. Different patterns reflect a variety of antigenic specificities that occur with different clinical pictures (see Box 11.16, p. 537). ANA is used as a screening test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc) – a negative ANA makes either condition highly unlikely – but low titres occur in RA and chronic infections and in normal individuals, especially the elderly (Table 11.3).

Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). These are detected by indirect immunofluorescent staining of fresh-frozen sections of rat liver or kidney or Hep-2 cell lines. Different patterns reflect a variety of antigenic specificities that occur with different clinical pictures (see Box 11.16, p. 537). ANA is used as a screening test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc) – a negative ANA makes either condition highly unlikely – but low titres occur in RA and chronic infections and in normal individuals, especially the elderly (Table 11.3).

Anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies. These are usually detected by a precipitation test (Farr assay), by ELISA, or by an immunofluorescent test using Crithidia luciliae (which contains double-stranded DNA). Raised anti-dsDNA is highly specific for SLE and the levels usually rise and fall in parallel with disease activity so can be used to monitor the level of treatment required.

Anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies. These are usually detected by a precipitation test (Farr assay), by ELISA, or by an immunofluorescent test using Crithidia luciliae (which contains double-stranded DNA). Raised anti-dsDNA is highly specific for SLE and the levels usually rise and fall in parallel with disease activity so can be used to monitor the level of treatment required.

Anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies (see Box 11.16, p. 537). These produce a speckled ANA fluorescent pattern, and can be identified by ELISA. The most commonly measured ENAs are:

Anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies (see Box 11.16, p. 537). These produce a speckled ANA fluorescent pattern, and can be identified by ELISA. The most commonly measured ENAs are:

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) (see p. 544). These are predominantly IgG autoantibodies directed against the primary granules of neutrophil and macrophage lysosomes. They are strongly associated with small-vessel vasculitis. Two major clinically relevant ANCA patterns are recognized on immunofluorescence:

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) (see p. 544). These are predominantly IgG autoantibodies directed against the primary granules of neutrophil and macrophage lysosomes. They are strongly associated with small-vessel vasculitis. Two major clinically relevant ANCA patterns are recognized on immunofluorescence:

Antiphospholipid antibodies (see p. 538). These are detected in the antiphospholipid syndrome (see p. 538).

Antiphospholipid antibodies (see p. 538). These are detected in the antiphospholipid syndrome (see p. 538).

Immune complexes. Immune complexes are infrequently measured, largely because of variability between assays and difficulty in interpreting their meaning. Assays based on the polyethylene glycol precipitation method (PEG) or C1q binding are available commercially.

Immune complexes. Immune complexes are infrequently measured, largely because of variability between assays and difficulty in interpreting their meaning. Assays based on the polyethylene glycol precipitation method (PEG) or C1q binding are available commercially.

Complement. Low complement levels indicate consumption and suggest an active disease process in SLE.

Complement. Low complement levels indicate consumption and suggest an active disease process in SLE.

Table 11.2 Conditions in which rheumatoid factor is found in the serum

Autoimmune rheumatic diseases | RF (IgM) % |

Rheumatoid arthritis | 70 |

Systemic lupus erythematosus | 25 |

Sjögren’s syndrome | 90 |

Systemic sclerosis | 30 |

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis | 50 |

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Variable |

Viral infections | Hyperglobulinaemias |

Hepatitis | Chronic liver disease |

Infectious mononucleosis | Sarcoidosis |

Cryoglobulinaemia |

|

Chronic infections | Normal population |

Tuberculosis | Elderly |

Leprosy | Relatives of people with RA |

Syphilis |

|

Table 11.3 Conditions in which serum antinuclear antibodies are found

| (%) | |

|---|---|

Systemic lupus erythematosus | 95 |

Systemic sclerosis | 70 |

Sjögren’s syndrome | 80 |

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis | 40 |

Rheumatoid arthritis | 30 |

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Variable |

Other diseases |

|

Autoimmune hepatitis | 100 |

Drug-induced lupus | >95 |

Myasthenia gravis | 50 |

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 30 |

Diabetes mellitus | 25 |

Infectious mononucleosis | 5–10 |

Normal population | 8 |

Joint aspiration

Examination of joint (or bursa) fluid is used mainly to diagnose septic, reactive or crystal arthritis. The appearance of the fluid is an indicator of the level of inflammation. The procedure is often undertaken in combination with injection of a corticosteroid. Aspiration alone is therapeutic in crystal arthritis (see Practical Box 11.2, p. 508).

Examination of synovial fluid

Polarized light microscopy is performed for crystals.

Gout: negatively birefringent, needle-shaped crystals of sodium urate

Gout: negatively birefringent, needle-shaped crystals of sodium urate

Pyrophosphate arthropathy (pseudogout): rhomboidal, weakly positively birefringent crystals of calcium pyrophosphate.

Pyrophosphate arthropathy (pseudogout): rhomboidal, weakly positively birefringent crystals of calcium pyrophosphate.

Diagnostic imaging and visualization

X-rays can be diagnostic in certain conditions (e.g. established rheumatoid arthritis) and are the first investigation in many cases of trauma. X-rays can detect joint space narrowing, erosions in rheumatoid arthritis, calcification in soft tissue, new bone formation, e.g. osteophytes and decreased bone density (osteopenia) or increased bone density (osteosclerosis):

X-rays can be diagnostic in certain conditions (e.g. established rheumatoid arthritis) and are the first investigation in many cases of trauma. X-rays can detect joint space narrowing, erosions in rheumatoid arthritis, calcification in soft tissue, new bone formation, e.g. osteophytes and decreased bone density (osteopenia) or increased bone density (osteosclerosis):

Ultrasound (US) is particularly useful for periarticular structures, soft tissue swellings and tendons and for detecting active synovitis in inflammatory arthritis. It is increasingly used to examine the shoulder and other structures during movement, e.g. shoulder impingement syndrome (see p. 500). Doppler US measures blood flow and hence inflammation. US is used to guide local injections.

Ultrasound (US) is particularly useful for periarticular structures, soft tissue swellings and tendons and for detecting active synovitis in inflammatory arthritis. It is increasingly used to examine the shoulder and other structures during movement, e.g. shoulder impingement syndrome (see p. 500). Doppler US measures blood flow and hence inflammation. US is used to guide local injections.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows bone changes and intra-articular structures in striking detail. Visualization of particular structures can be enhanced with different resonance sequences. T1-weighted is used for anatomical detail, T2-weighted for fluid detection and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) for the presence of bone marrow oedema. It is more sensitive than X-rays in the early detection of articular and periarticular disease. It is the investigation of choice for most spinal disorders but is inappropriate in uncomplicated mechanical low back pain. Gadolinium injection enhances inflamed tissue. MRI can also detect muscle changes, e.g. myositis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows bone changes and intra-articular structures in striking detail. Visualization of particular structures can be enhanced with different resonance sequences. T1-weighted is used for anatomical detail, T2-weighted for fluid detection and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) for the presence of bone marrow oedema. It is more sensitive than X-rays in the early detection of articular and periarticular disease. It is the investigation of choice for most spinal disorders but is inappropriate in uncomplicated mechanical low back pain. Gadolinium injection enhances inflamed tissue. MRI can also detect muscle changes, e.g. myositis.

Computerized axial tomography (CT) is useful for detecting changes in calcified structures but dose of irradiation is high.

Computerized axial tomography (CT) is useful for detecting changes in calcified structures but dose of irradiation is high.

Bone scintigraphy utilizes radionuclides, usually 99mTc, and detects abnormal bone turnover and blood circulation and, although nonspecific, helps in detecting areas of inflammation, infection or malignancy. It is best used in combination with other anatomical imaging techniques.

Bone scintigraphy utilizes radionuclides, usually 99mTc, and detects abnormal bone turnover and blood circulation and, although nonspecific, helps in detecting areas of inflammation, infection or malignancy. It is best used in combination with other anatomical imaging techniques.

DXA scanning uses very low doses of X-irradiation to measure bone density and is used in the screening and monitoring of osteoporosis.

DXA scanning uses very low doses of X-irradiation to measure bone density and is used in the screening and monitoring of osteoporosis.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning uses radionuclides, which decay by emission of positrons. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake indicates areas of increased glucose metabolism. It is used to locate tumours and demonstrate large vessel vasculitis, e.g. Takayasu’s arteritis (see p. 789). PET scans are combined with CT to improve anatomical details.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning uses radionuclides, which decay by emission of positrons. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake indicates areas of increased glucose metabolism. It is used to locate tumours and demonstrate large vessel vasculitis, e.g. Takayasu’s arteritis (see p. 789). PET scans are combined with CT to improve anatomical details.

Arthroscopy is a direct means of visualizing a joint, particularly the knee or shoulder. Biopsies can be taken, surgery performed in certain conditions (e.g. repair or trimming of meniscal tears), and loose bodies removed.

Arthroscopy is a direct means of visualizing a joint, particularly the knee or shoulder. Biopsies can be taken, surgery performed in certain conditions (e.g. repair or trimming of meniscal tears), and loose bodies removed.

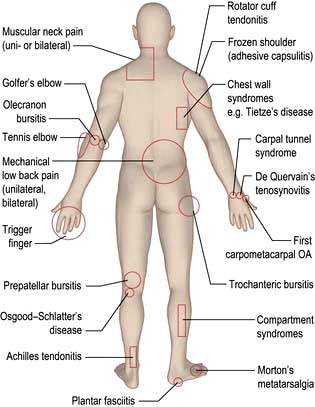

Common regional musculoskeletal problems (fig. 11.2)

Pain in the neck and shoulder (Table 11.4)

Mechanical or muscular neck pain (shoulder girdle pain)

Table 11.4 Pain in the neck and shoulder

Spondylosis seen on X-ray increases after the age of 40 years, but it is not always causal. Spondylosis can, however, cause stiffness and increases the risk of mechanical or muscular neck pain. Muscle spasm is palpable and tender and may lead to abnormal neck posture (e.g. acute torticollis). Muscular-pattern neck pain is not localized but affects the trapezius muscle, the C7 spinous process and the paracervical musculature (shoulder girdle pain). Pain often radiates upwards to the occiput and is commonly associated with tension headaches. These features are also seen in chronic widespread pain (see p. 509).

Treatment

Patients are given short courses of analgesic therapy along with reassurance and explanation. Physiotherapists can help to relieve spasm and pain, teach exercises and relaxation techniques, and improve posture. An occupational therapist can advise about the ergonomics of the workplace if the problem is work-related (see p. 510).

Nerve root entrapment

Acute cervical disc prolapse presents with unilateral pain in the neck, radiating to the interscapular and shoulder regions. This diffuse, aching dural pain is followed by sharp, electric shock-like pain down the arm, in a nerve root distribution, often with pins and needles, numbness, weakness and loss of reflexes (Table 11.5).

Cervical spondylosis occurs in the older patient with posterolateral osteophytes compressing the nerve root and causing root pain (see Fig. 22.58, p. 1148), commonly at C5/C6 or C6/C7; it is seen on oblique radiographs of the neck. An MRI scan clearly distinguishes facet joint OA, root canal narrowing and disc prolapse.

Treatment

A support collar, rest, analgesia and sedation are used initially as necessary. Patients should be advised not to carry heavy items. It usually recovers in 6–12 weeks. MRI is the investigation of choice if surgery is being considered or the diagnosis is uncertain (Fig. 11.3). A cervical root block administered under direct vision by an experienced pain specialist may relieve pain while the disc recovers. Neurosurgical referral is essential if the pain persists or if the neurological signs of weakness or numbness are severe or bilateral. Bilateral root pain with or without long track symptoms or signs is a neurosurgical emergency because a central disc prolapse may compress the cervical spinal cord. Posterior osteophytes may cause spinal claudication and cervical myelopathy.

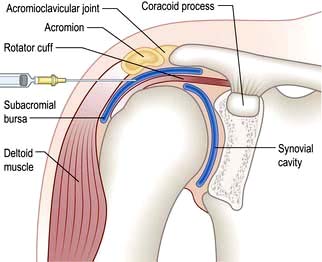

Pain in the shoulder

The shoulder is a shallow joint with a large range of movement. The humeral head is held in place by the rotator cuff (Fig. 11.4) which is part of the joint capsule. It comprises the tendons of infraspinatus and teres minor posteriorly, supraspinatus superiorly and teres major and subscapularis anteriorly. The rotator cuff (particularly supraspinatus) prevents the humeral head blocking against the acromion during abduction; the deltoid pulls up and the supraspinatus pulls in to produce a turning movement and the greater tuberosity glides under the acromion without impingement. Shoulder pathology restricts or is made worse by shoulder movement. Specific diagnoses are difficult to make clinically but this may not matter for pain management.

Pain in the shoulder can sometimes be due to problems in the neck. The differential diagnosis of this is shown in Box 11.1. Adhesive capsulitis (true frozen shoulder) is uncommon (see below). Early inflammatory arthritis and polymyalgia rheumatica in the elderly may present with shoulder pain. Shoulder pain is more common in diabetic patients than in the general population.

![]() Box 11.1

Box 11.1

Differential diagnosis of ‘shoulder’ pain

Rotator cuff tendonitis pain is worse at night and radiates to the upper arm.

Rotator cuff tendonitis pain is worse at night and radiates to the upper arm.

Painful shoulders produce secondary muscular neck pain.

Painful shoulders produce secondary muscular neck pain.

Muscular neck pain (also known as shoulder girdle pain) does not radiate to the upper arm.

Muscular neck pain (also known as shoulder girdle pain) does not radiate to the upper arm.

Cervical nerve root pain is usually associated with pins and needles or neurological signs in the arm.

Cervical nerve root pain is usually associated with pins and needles or neurological signs in the arm.

Rotator cuff (supraspinatus) tendonosis

Treatment

Analgesics, NSAIDs and/or physiotherapy may suffice, but severe pain responds to an injection of corticosteroid into the subacromial bursa (Fig. 11.4). Patients should be warned that 10% will develop worse pain for 24–48 hours after injection. Some 70% improve over 5–20 days and mobilize the joint themselves. Physiotherapy helps persistent stiffness. Further ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injections may be needed but the long-term benefit is unclear.

Pain in the elbow

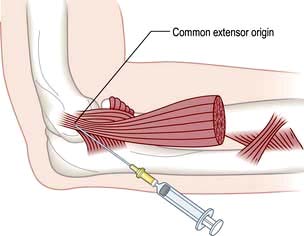

Epicondylitis

Treatment

Advise rest and arrange review by a physiotherapist. A local injection of corticosteroid at the point of maximum tenderness is helpful when the pain is severe but needs physiotherapy follow-up to prevent recurrences (Fig. 11.5). Avoid the ulnar nerve when injecting golfer’s elbow. Both conditions settle spontaneously eventually, but occasionally persist and require surgical release.

Pain in the hand and wrist (table 11.6)

Table 11.6 Pain in the hand and wrist: causes

| All ages | Older patients |

|---|---|

Trauma/fractures | Nodal OA: |

Tenosynovitis: | DIPs (Heberden’s nodes) |

Flexor with/without triggering | PIPs (Bouchard’s nodes) |

Dorsal | |

De Quervain’s | Trauma – scaphoid fracture |

Pseudogout | |

Gout: | |

Acute | |

Tophaceous | |

|

DIPs, PIPs, distal and proximal interphalangeal joints.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

This is due to median nerve compression in the limited space of the carpal tunnel. Thickened ligaments, tendon sheaths or bone enlargement can cause it, but it is usually idiopathic. (Causes are discussed on p. 1144.) The history is usually typical and diagnostic with the patient waking with numbness, tingling and pain in a median nerve distribution. The pain radiates to the forearm. The fingers feel swollen but usually are not. Wasting of the abductor pollicis brevis develops with sensory loss in the radial three and a half fingers. The pain may be produced by tapping the nerve in the carpal tunnel (Tinel’s sign) or by holding the wrist in flexion (Phalen’s test).

Other conditions causing pain

Nodal osteoarthritis. This affects the DIP and less commonly PIP joints, which are initially swollen and red. The inflammation and pain settle but bony swellings remain (p. 514).

Pain in the lower back

Low back pain is a common symptom. It is often traumatic and work-related, although lifting apparatus and other mechanical devices and improved office seating help to avoid it. Episodes are generally short-lived and self-limiting, and patients attend a physiotherapist or osteopath more often than a doctor. Chronic back pain is the cause of 14% of long-term disability in the UK. The causes are listed in Table 11.7, and the management of back pain is summarized in Box 11.2.

Table 11.7 Pain in the back (lumbar region): causes

Mechanical |

Inflammatory |

Metabolic |

Neoplastic (see p. 589) |

Referred pain |

![]() Box 11.2

Box 11.2

Management of back pain

Most back pain presenting to a primary care physician needs no investigation.

Most back pain presenting to a primary care physician needs no investigation.

Pain between the ages of 20 and 55 years is likely to be mechanical and is managed with analgesia, brief rest if necessary and physiotherapy.

Pain between the ages of 20 and 55 years is likely to be mechanical and is managed with analgesia, brief rest if necessary and physiotherapy.

Patients should stay active within the limits of their pain.

Patients should stay active within the limits of their pain.

Early treatment of the acute episode, advice and exercise programmes reduce long-term problems and prevent chronic pain syndromes.

Early treatment of the acute episode, advice and exercise programmes reduce long-term problems and prevent chronic pain syndromes.

Physical manipulation of uncomplicated back pain produces short-term relief and enjoys high patient satisfaction ratings.

Physical manipulation of uncomplicated back pain produces short-term relief and enjoys high patient satisfaction ratings.

Psychological and social factors may influence the time of presentation.

Psychological and social factors may influence the time of presentation.

Investigations

Spinal X-rays are required only if the pain is associated with certain ‘red flag’ symptoms or signs, which indicate a high risk of more serious underlying problems:

Spinal X-rays are required only if the pain is associated with certain ‘red flag’ symptoms or signs, which indicate a high risk of more serious underlying problems:

MRI is preferable to CT scanning when neurological signs and symptoms are present. CT scans demonstrate bony pathology better. Interpretation of the relevance of the findings may require a specialist opinion.

MRI is preferable to CT scanning when neurological signs and symptoms are present. CT scans demonstrate bony pathology better. Interpretation of the relevance of the findings may require a specialist opinion.

Bone scans are useful in infective and malignant lesions but are also positive in degenerative lesions.

Bone scans are useful in infective and malignant lesions but are also positive in degenerative lesions.

Full blood count, ESR and biochemical tests are required only when the pain is likely to be due to malignancy, infection or a metabolic cause. Normal ESR and CRP distinguish mechanical back pain from polymyalgia rheumatica, a likely differential in the elderly.

Full blood count, ESR and biochemical tests are required only when the pain is likely to be due to malignancy, infection or a metabolic cause. Normal ESR and CRP distinguish mechanical back pain from polymyalgia rheumatica, a likely differential in the elderly.

Mechanical low back pain

Examination and management

pre-existing chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia)

pre-existing chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia)

psychosocial factors such as high levels of psychological distress, poor self-rated health and dissatisfaction with employment.

psychosocial factors such as high levels of psychological distress, poor self-rated health and dissatisfaction with employment.

Spinal movement occurs at the disc and the posterior facet joints, and stability is normally achieved by a complex mechanism of spinal ligaments and muscles. Any of these structures may be a source of pain. An exact anatomical diagnosis is difficult, but some typical syndromes are recognized (see below). They are often associated with but not necessarily caused by radiological spondylosis (see p.1148).

Postural back pain develops in individuals who sit in poorly designed, unsupportive chairs.

Reactive changes develop in adjacent vertebrae; the bone becomes sclerotic and osteophytes form around the rim of the vertebra (Fig. 11.6). The most common sites of lumbar spondylosis are L5/S1 and L4/L5.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree