Reproductive System Disorders

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, the student is expected to:

1. Describe the causes of infertility in males and females.

2. Describe the common congenital abnormalities in males and females.

3. Compare benign prostatic hypertrophy with cancer of the prostate.

4. Describe the incidence and pathophysiology of testicular cancer.

5. Compare the common menstrual disorders.

6. Describe endometriosis and its complications.

7. Explain how pelvic inflammatory disease develops and its effects.

8. Describe the breast lesions, fibrocystic breast disease, and breast cancer.

9. Compare the common benign and malignant tumors in the cervix, uterus, and ovaries.

Key Terms

dyspareunia

exogenous

gynecomastia

hirsutism

lactation

leukorrhea

meatus

menarche

spermatogenesis

Disorders of the Male Reproductive System

Review of the Male Reproductive System

Structure and Function

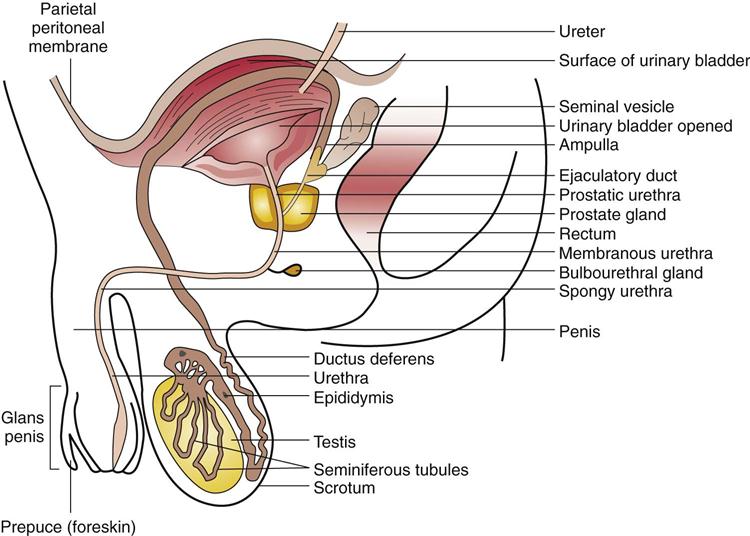

The male gonads, the testes, are suspended by the spermatic cord in the scrotum, a sac outside the abdominal cavity (Fig. 19-1). The testes constantly produce sperm and the sex hormone testosterone.

The scrotal sac consists of a layer of skin that is continuous with the skin of the perineal area plus an inner muscle layer and fascia. The scrotal covering is loose and falls into folds or rugae. A connective tissue septum separates the two testes within the scrotum. Each testis and attached epididymis is enclosed in the tunica vaginalis, a double-walled membrane with a small amount of fluid between the layers (see Fig. 19-1). The spermatic cord contains arteries, veins, and lymphatics for the testes (see Fig. 19-3).

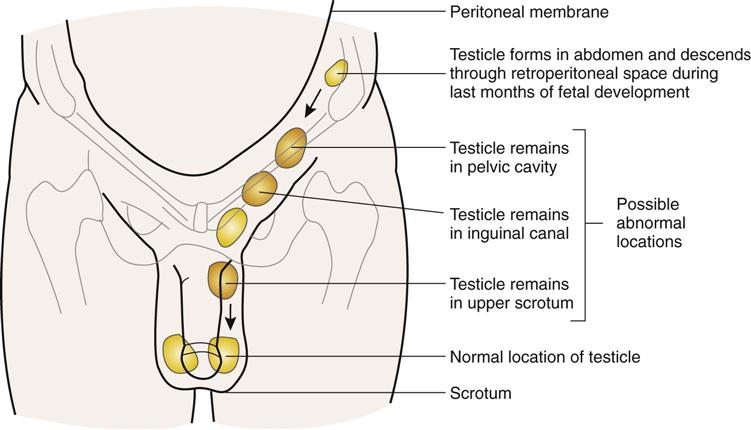

The testes are positioned outside the abdominal cavity to provide an optimum temperature for sperm production, 2°F to 3°F (1°C to 2°C) below normal body temperature. The scrotal muscle draws the testes closer to the body whenever the environmental temperature drops. When the temperature climbs, the muscle relaxes, letting the testes drop away from the body. The fetal testes descend from the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal into the scrotum during the third trimester of pregnancy. Then the inguinal canal closes (see Fig. 19-2).

At puberty the testes mature and begin to produce sperm and testosterone under the influence of the gonadotropins secreted by the adenohypophysis. In addition to the testes, the male reproductive system includes an extensive duct system connected to accessory glands and structures that form and transport the semen preparatory to ejaculation from the penis during sexual intercourse (see Fig. 19-1).

Spermatogenesis, the production of spermatozoa, is a continuous process. It takes approximately 60 to 70 days to complete the process of development.

2. Efferent ducts conduct the multitudes of sperm into the epididymis, where the sperm mature.

3. Peristaltic movements in the epididymis assist the sperm to move on into the ductus deferens (vas deferens) and then to the ampulla, where the now-motile sperm may be stored for several weeks until ejaculation occurs (see Fig. 19-1). Vasectomy, which is one method of birth control, involves cutting or obstructing the vas deferens to block the passage of sperm.

When semen is formed at the time of emission, fluid containing many substances is gathered from the various accessory structures entering the ejaculatory duct and urethra:

The total volume of semen ejaculated at one time is 2 to 5 mL. Semen consists primarily of fluid, but contains 1 to 2 hundred million sperm.

Hormones

Gonadotropic hormones released by the adenohypophysis or anterior pituitary gland include:

Testosterone is essential for the maturation of sperm. Serum levels of testosterone provide a negative feedback system for the continuous control of gonadotropin secretions, there being no cyclic hormones in males (see Chapter 16). Other functions of testosterone include the development and maintenance of secondary sex characteristics such as male hair distribution, deeper voice, and maturing of the male external genitalia. Also, testosterone is an anabolic steroid hormone that promotes protein metabolism and skeletal muscle development, influencing the physical changes seen in the adolescent male (see Chapter 23). These steroid hormones are being abused more frequently by both males and females who are athletes or are interested in body building or altered body image. Unfortunately, serious adverse effects are associated with such use, such as liver damage, cardiovascular disease, and damage to the reproductive structures.

Congenital Abnormalities of the Penis

Epispadias and Hypospadias

Epispadias refers to a urethral opening on the dorsal (upper) surface of the penis, proximal to the glans. If the urethral defect extends proximally and affects the urinary sphincter, incontinence may result. Infections may result from stricture at the opening.

In some cases, this condition is associated with exstrophy of the bladder, which is a failure of the abdominal wall to form across the midline.

Hypospadias is a urethral opening on the ventral (under) surface of the penis. If the opening occurs in the proximal section of the penis, it is considered more severe and may be accompanied by chordee, ventral curvature of the penis. Other abnormalities such as cryptorchidism are often associated with hypospadias. Surgical reconstruction, which may be performed in stages, is recommended for both epispadias and hypospadias to provide normal urinary flow and normal sexual function.

Disorders of the Testes and Scrotum

Cryptorchidism

Maldescent of the testis, or cryptorchidism, occurs when one of the testes fails to descend into the normal position in the scrotum during the latter part of pregnancy (Fig. 19-2). The testis may remain in the abdominal cavity or discontinue the descent at some point in the inguinal canal or above the scrotum. In some cases, the testis assumes an abnormal position outside the scrotum; this is called an ectopic testis. In many cases, spontaneous descent occurs during the first year after birth.

The reason for maldescent is not fully understood. Possible factors include hormonal abnormalities, a short spermatic cord, or a small inguinal ring. If the testis remains undescended, the seminiferous tubules degenerate, and spermatogenesis is impaired.

Of concern is the increased risk of testicular cancer in cryptorchid testes (see Chapter 23). Therefore, surgical positioning of the testes in the scrotum before age 2 is advisable.

Hydrocele, Spermatocele, and Varicocele

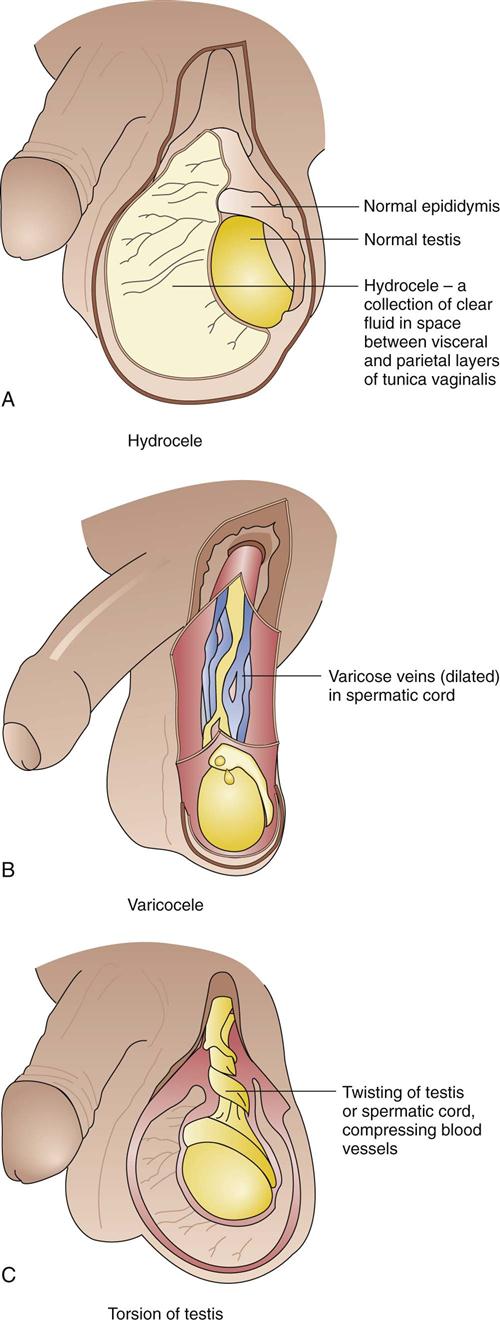

Hydrocele occurs when excessive fluid collects in the potential space between the layers of the tunica vaginalis (Fig. 19-3A). This may occur around one or both testes and can be distinguished by transillumination.

Hydrocele may occur as a congenital defect in a newborn when peritoneal fluid accumulates in the scrotum. This fluid may be reabsorbed in time. The fluid may continue to escape from the peritoneal cavity if the proximal portion of the processus vaginalis, a section of peritoneal membrane, does not close off as expected following descent of the testes. Usually the scrotum fills with more fluid during the day, becoming larger and firmer, and then the fluid subsides during the night.

The other common finding in an infant in whom the processus vaginalis remains open is an inguinal hernia, which is a loop of intestine that passes through the abnormal opening (see Fig. 17-41). Such a hernia usually leads to intestinal obstruction. Surgical repair is recommended if the opening remains patent or herniation persists because there is a risk that the herniated intestinal loop may become strangulated.

Acquired hydrocele may result from scrotal injury, an infection, a tumor, or unknown causes. Acquired hydroceles are more common after middle age. Large amounts of fluid may compromise the blood supply to the testis, requiring aspiration.

A spermatocele is a cyst containing fluid and sperm that develops between the testis and the epididymis outside the tunica vaginalis. It may be related to an abnormality of the tubules. If the cyst is large, it may be surgically removed.

A varicocele is a dilated vein in the spermatic cord, usually on the left side. It frequently develops after puberty and results from a lack of valves in the veins, permitting backflow of blood and increased pressure in the veins. Varicocele may be mild, and scrotal support minimizes the heavy feeling. If it is extensive, the varicocele is painful or tender and leads to infertility because of the impaired blood flow to the testes and decreased spermatogenesis. In this case, surgical treatment of the abnormal veins is necessary.

Torsion of the testis occurs when the testis rotates on the spermatic cord, compressing the arteries and veins. Ischemia develops, and the scrotum swells. Immediate treatment is required manually and surgically to restore blood flow to the testis. Testicular torsion frequently occurs during puberty, both spontaneously and following trauma.

Inflammation and Infections

Prostatitis

The National Institutes of Health recognizes four categories of prostatitis: category 1, acute bacterial; category 2, chronic bacterial; category 3, nonbacterial; and category 4, asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis. It is considered an ascending infection or inflammation with multiple causes. The prostate is somewhat protected from ascending infection by the flushing action of urination and ejaculation and by an intact mucous membrane. Also, the prostatic secretions contain antimicrobial factors. However, the close association of the male reproductive tract with the urinary tract, including the continuous mucosa, promotes the spread of infection through the structures, and prostatitis is therefore closely associated with urinary tract infections.

The causes of the common nonbacterial form of prostatitis and prostatodynia (painful prostate) have not been established.

Pathophysiology

Acute bacterial prostatitis causes a tender, swollen gland, typically soft and boggy on palpation. The urine contains large quantities of microorganisms, pus, and leukocytes. Expressed prostatic secretions also contain many organisms, confirming the source of the infection. However, this process may be painful and may actually spread the infection or cause bacteremia in acute cases.

Nonbacterial prostatitis is indicated by large numbers of leukocytes in the urine and prostatic secretions, although the prostate gland is not markedly enlarged.

In patients with chronic prostatitis the prostate is only slightly enlarged, irregular, and firm because fibrosis is more extensive. In most cases of prostatitis the urinary tract is infected and signs of dysuria, frequency, and urgency occur. Other parts of the reproductive tract (e.g., the epididymis or testes) may be involved as well.

Etiology

Acute bacterial prostatitis is usually an ascending infection (it progresses up the urethra) and is caused primarily by Escherichia coli but sometimes by Pseudomonas, Proteus, or Streptococcus faecalis.

• In young men in association with urinary tract infections due to invasion by coliform bacteria from the intestines (see Chapter 18)

• In older men with benign prostatic hypertrophy

• In association with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as gonorrhea

• With instrumentation such as catheterization

Chronic prostatitis is usually related to repeated infection by E. coli.

Signs and Symptoms

Although both acute and chronic infections are manifested by dysuria, urinary frequency, and urgency, similar to cystitis, the acute infection is usually accompanied by fever and chills. Low back pain or lower abdominal discomfort may be present. Severe inflammation in the prostate may cause obstruction of the urinary flow through the urethra, resulting in a decreased urinary stream, hesitancy in initiating urination, incomplete bladder emptying, and nocturia or frequency. Systemic signs include fever, malaise, anorexia, and muscle aching. In non-bacterial prostatitis, the urinary signs are present, often intermittently, but the systemic signs are less marked.

Treatment

Antibacterial drugs such as ciprofloxacin (Cipro) are recommended for bacterial infections. Follow-up tests should confirm complete eradication. Nonbacterial prostatitis can be treated by anti-inflammatory drugs as well as by prophylactic antibacterials.

Balanitis

Balanitis is a fungal infection of the glans penis that can be transmitted during sexual activity. The fungus, Candida albicans, causes the infection primarily in uncircumcised males. Balanitis first appears as penile vesicles which later develop into patches that cause severe burning and itching. Diagnosis is accomplished by the identification of the presence of Candida. Treatment is done with topical antifungal medications such as Miconazole, Tolnaftate and Clotrimazole.

Tumors

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

Pathophysiology

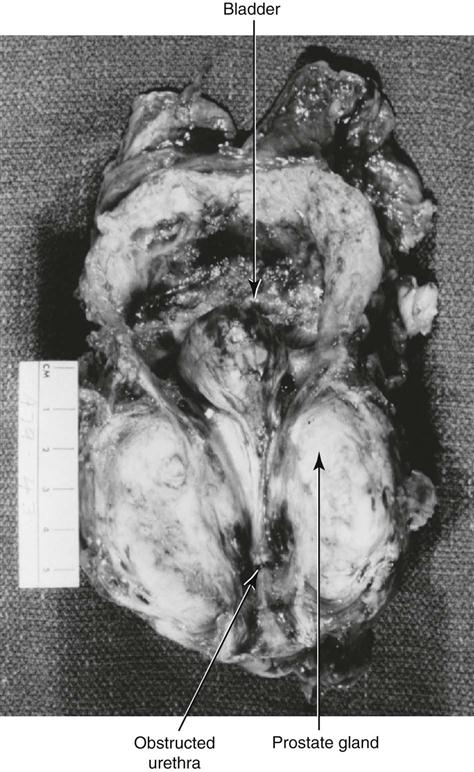

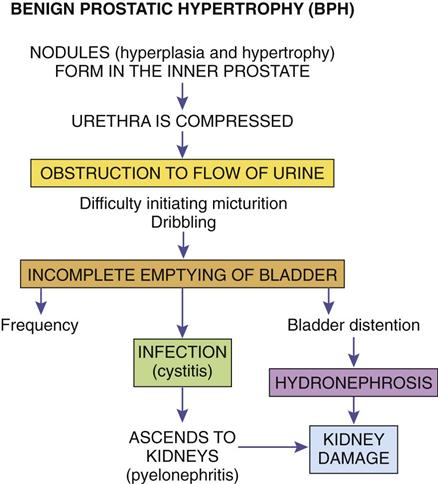

Benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is a very common disorder in older men, with an estimated 50% of men over 65 years experiencing some form varying from mild to severe. Although called hypertrophy, the change is actually hyperplasia of the prostatic tissue with formation of nodules surrounding the urethra. These changes lead to compression of the urethra and variable degrees of urinary obstruction (Fig. 19-4). This hyperplasia appears to be related to an imbalance between estrogen and testosterone that results from the hormonal changes associated with aging. No connection between BPH and prostatic carcinoma has been identified.

Rectal examination reveals an enlarged gland. Incomplete emptying of the bladder due to the obstruction leads to frequent infections (Fig. 19-5). Continued obstruction causes a distended bladder, dilated ureters, hydronephrosis, and possible renal damage (see Chapter 18). If significant obstruction and urinary retention develop in the patient, surgical intervention, using one of several techniques, is required.

Signs and Symptoms

The initial signs indicate obstruction of urinary flow. Hesitancy, dribbling, and decreased force of the urinary stream are direct results of the narrowed urethra. Incomplete bladder emptying leads to frequency, nocturia, and recurrent urinary tract infection.

Treatment

Only a small percentage of cases require intervention. Drugs to reduce the androgenic effects and slow nodular growth include Avodart (dutasteride). When surgery is not desirable, alpha-adrenergic blockers such as Flomax (tamsulosin) relax smooth muscle in the prostate and bladder, resulting in increased flow of urine. A combination of Proscar (finasteride) and Cardura (doxazosin) has been shown to greatly reduce the progression of hypertrophy and possible obstruction of the urethra. Surgery may be recommended when obstruction is severe and several procedures are available. Choice depends on the man’s overall health status and the degree of obstruction.

Cancer of the Prostate

Prostate cancer is common in men older than 50 years and ranks high as a cause of cancer death in men. The National Cancer Institute of the NIH estimated that in 2013 there will be 238,590 new cases of prostate cancer in the United States resulting in 29,720 deaths, which is the second leading cause of death from cancer in men. One in six men is expected to develop prostatic cancer during their lifetime.

Pathophysiology

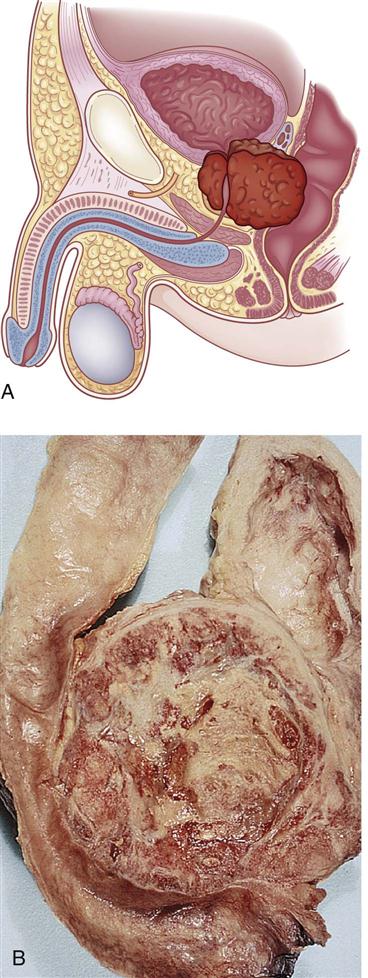

Most tumors are adenocarcinomas arising from the tissue near the surface of the gland (rather than in the central area, as in BPH). There may be more than one focus of neoplastic cells. Tumors vary in degree of cellular differentiation; the more undifferentiated or anaplastic tumors are much more aggressive, growing and spreading at a faster rate. Many tumors are androgen dependent.

Prostate cancer is both invasive to regional tissues such as lymph nodes or urethra and, metastatic to bone (Fig. 19-6). With better screening of men older than 50 years for this cancer many individuals are being diagnosed in earlier stages than in the past. Five-year survival rates vary considerably: Localized cancers have a 100% survival rate, whereas regional spread reduces the rate to 89%, and distant metastases of bone or other organs have a 37% survival rate.

Etiology

Five to ten percent of prostatic cancers are caused by inherited mutations, and the mutation in the HPC1 gene has been identified as the cause of these cancers. Other causes include high androgen levels (either intrinsic or extrinsic), increased insulinlike growth factor, and recurrent prostatitis. Prostatic cancer is common in North America and northern Europe but not in countries farther east. The incidence is higher in the African-American population than in Caucasians, indicating a possible genetic factor. Testosterone receptors are found on cancer cells. Note that BPH alone does not predispose to prostatic cancer.

Signs and Symptoms

A hard nodule in the periphery of the gland, often in the posterior lobe, may be detected on digital rectal examination. The tumor tends not to cause early urethral obstruction because of its location. As the tumor develops, some obstruction occurs, producing signs of hesitancy, a decreased stream, urinary frequency, or bladder infection (cystitis).

Diagnostic Tests

Two serum markers are helpful—prostate specific antigen (PSA), which provides a useful screening tool for early detection as well as supportive data for the diagnosis, and prostatic acid phosphatase, which is elevated when metastatic cancer is present. Prostate specific antigen may be elevated with BPH or infection, so it is not diagnostic by itself and there have been false positive and false negative results. These serum markers may be useful in monitoring the effectiveness of treatment. It is recommended that all men older than age 50 be tested regularly. Men who are considered high risk for prostatic cancer due to ethnicity or family history should begin testing at age 45.

Ultrasonography using a small ultrasound probe and biopsy confirm the diagnosis. Bone scans and monoclonal antibody scans are useful for detecting early metastases.

Diagnosis is based on three criteria: an elevated PSA, abnormality on digital rectal exam, and biopsy results, which are expressed as a numeric value based on the Gleason scale, which is based on the proportion of abnormal cells present in the biopsy specimen.

Treatment

Surgery (radical prostatectomy) and radiation (including implants) are the treatments of choice. There is risk of impotence or incontinence. When the tumor is androgen sensitive, orchiectomy (removal of the testes) or antitestosterone drug therapy (e.g., flutamide [Euflex]) may be suggested to reduce hormonal effects. New chemotherapy protocols are now in clinical trials. Approximately 30% of men deemed “cured” have a recurrence of the cancer after 5 years.

Cancer of the Testes

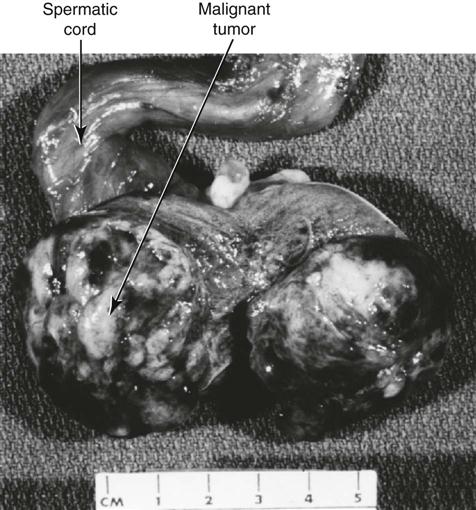

Benign tumors of the testes are extremely rate and the majority of tumors that occur in the testes are malignant, arising from germ cells. Although testicular cancer is not common, with about 1 in 300 men being affected during their lifetime, there is concern because it occurs primarily in the 15- to 35-year-old age group, and the incidence is increasing. The cause for the increase in cases is not known. Testicular cancer is the most common solid tumor in young men. Certain types of testicular cancer may occur in other groups, such as younger children or older males. For this reason, regular monthly testicular self-examination is recommended to check for an unusual hard mass. Illustrated instructions are available from The American Cancer Society and medical clinics.

Pathophysiology

Testicular cancer may originate from one type of cell, for example, a seminoma, or may be mixed, consisting of cells from a variety of sources and with varying degrees of differentiation. A teratoma consists of a mixture of different germ cells (Fig. 19-7). A common mixed tumor is a teratoma, derived from one or more of the germ cell layers, combined with an embryonal carcinoma, which has poorly differentiated cells.

Some malignant tumors secrete human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), which serve as a useful serum marker for both diagnosis and follow-up monitoring.

Some testicular neoplasms may spread at an early stage, for example, choriocarcinoma, whereas others, such as seminomas, remain localized for a more prolonged period. Testicular tumors follow a typical pattern when spreading, first appearing in the common iliac and para-aortic lymph nodes and then in the mediastinal and supraclavicular lymph nodes. Metastases spreading through the blood to the lungs, liver, bone, and brain occur at a later time.

Several staging systems are used, based on the extent of the primary tumor, the degree of lymph node involvement (retroperitoneal or otherwise), and the presence of distant metastases.

Etiology

This tumor has a heredity pattern with change in chromosome number 12 in some families and there is a possible relationship with infection or trauma. An established predisposing factor is cryptorchidism, or maldescent of the testes.

Signs and Symptoms

Testicular tumors present as hard, painless, usually unilateral masses. The testis may be enlarged or may feel heavy. Eventually there may be a dull aching pain in the lower abdomen. In some cases, hydrocele or epididymitis may develop because of inflammation, or gynecomastia (enlarged breasts) may become evident if hormones are secreted by the tumor.

Diagnostic Tests

Tests such as ultrasound, computed tomography scans, and lymphangiography, and the presence of tumor markers (e.g., AFP and hCG) are useful in diagnosis. If a solid mass is seen during diagnostic imaging, surgical removal of the entire testis is done rather than a local biopsy of the mass. This is done to reduce the possibility of spread of tumor cells.

Treatment

Treatment of testicular cancer using a combination of surgery (orchiectomy), radiation therapy, and sometimes chemotherapy has greatly improved the prognosis. Orchiectomy does not usually interfere with sexual function. However, radiation or chemotherapy may temporarily reduce fertility for a few months. Men who are scheduled for these treatments may wish to consider sperm banking before the procedure. Cancer cells are not transmitted in the semen.

Disorders of the Female Reproductive System

Review of the Female Reproductive System

Structure and Function

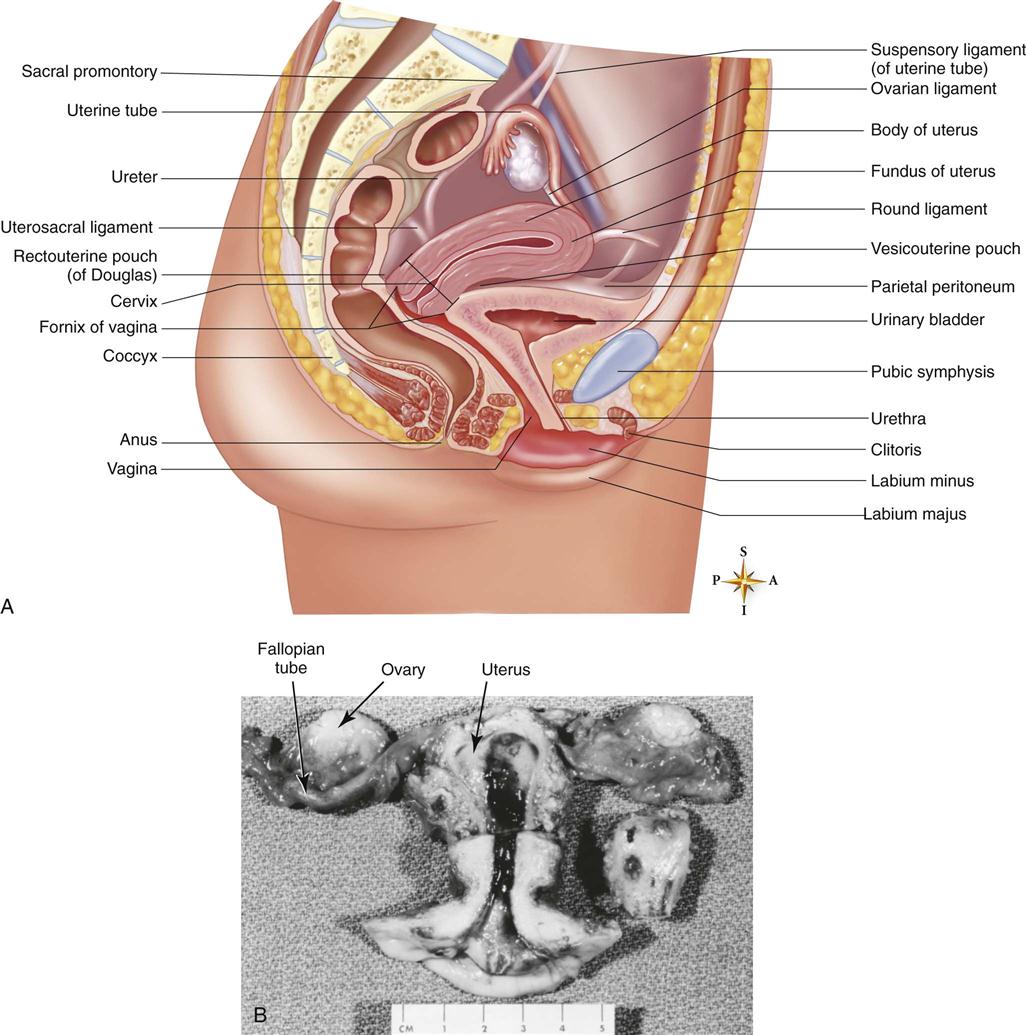

The female external genitalia or vulva include the mons pubis, labia, clitoris, and vaginal orifice. The mons pubis consists of the adipose tissue and hair covering the symphysis pubis. The labia majora, the outer fold, and the labia minora inside it are long, thin folds of skin extending back and down from the mons pubis, protecting the orifices. Sebaceous glands and sweat glands are located in the folds. The clitoris is a small projection of erectile tissue located anterior to the urethra. It is analogous to the male penis and is very sensitive to touch. In the vagina, the entryway to the reproductive tract, the orifice or introitus is situated between the urethral meatus (anterior) and the anus (posterior) (Fig. 19-8). The vagina is a muscular, distensible canal extending upward from the vulva to the cervix. It is lined with a mucosal membrane and falls in rugae or folds, allowing expansion during coitus (intercourse) or childbirth. The mucosa consists of stratified squamous epithelial cells, which are hormone sensitive. This mucous membrane is continuous up through the uterus and fallopian tubes, enabling the spread of infection. Following menopause and the decline in estrogen secretions, the mucosa becomes thin and fragile.

A, Diagram (sagittal section) of pelvis showing location of female reproductive organs. B, Ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina of a postmenopausal woman. Note the relative sizes of the structures. (A, From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy & Physiology, ed 8, St. Louis, 2013, Mosby. B, Courtesy of R.W. Shaw, MD, North York General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.)

Bartholin’s glands (the greater vestibular glands) are located on either side of the vaginal orifice and secrete mucus in response to sexual stimulation to facilitate penile penetration into the vagina during intercourse. Skene’s glands, located by the external urethral meatus, also secrete mucus to keep the tissues moist. Both of these sets of mucus-secreting glands are easily obstructed and infected. Leukorrhea, the normal vaginal discharge, is produced by these glands; the secretions are relatively clear or whitish and contain mucus and sloughed cells. The amount fluctuates during the menstrual cycle. Before puberty and after menopause vaginal pH is around 7, but during the reproductive years it is more acidic, between 4 and 5, due to an increased population of Lactobacillus. The acidic pH and the thickness of the epithelium provide protection against infection.

The upper vagina surrounds the cervix, which is the lower part or neck of the uterus. The endocervical canal is the passageway between the internal os of the cervix at the uterine end and the external os at the vaginal end. The external os is a small opening filled with thick mucus that acts as a barrier to vaginal flora attempting to ascend into the uterus. The lining of the endocervical canal is continuous with that of the uterus and the vagina but differs in composition. The endocervical canal is lined with columnar epithelial cells, which change to squamous epithelium in the vagina. The point of change is known as the transformation zone or squamous-columnar junction, and this is the common site of cervical dysplasia and cancer.

The uterus is a muscular sac within which a fertilized ovum may be implanted and develop. Note the relative sizes of the uterus and other structures in Figure 19-8. The pear-shaped body of the uterus is called the corpus. It is loosely suspended by ligaments in the pelvic cavity to allow for expansion during pregnancy. Normally it is anteverted, or tipped forward, resting on the urinary bladder (see Fig. 19-8).

The uterine wall is made up of three layers: the outer perimetrium or parietal peritoneum, the thick, middle layer of smooth muscle or myometrium, and the inner endometrium. The endometrium consists of a functional layer that is responsive to hormones during the menstrual cycle and an underlying basal layer that is responsible for the regeneration of the endometrium following menses.

The two fallopian tubes (oviducts) originate near the top of the uterus, just under the fundus, the top part of the corpus. Each tube curves up and out, ending in a flared opening over the ovary. This end portion has a fringe of fimbriae, moving finger-like projections that draw the released ovum into the tube. Cilia and peristaltic movements in the fallopian tube continue to move the ovum toward the uterus. Usually the ovum is fertilized by a sperm in the distal fallopian tube, and then it continues on to the uterus, where it is implanted at a suitable site in the endometrium.

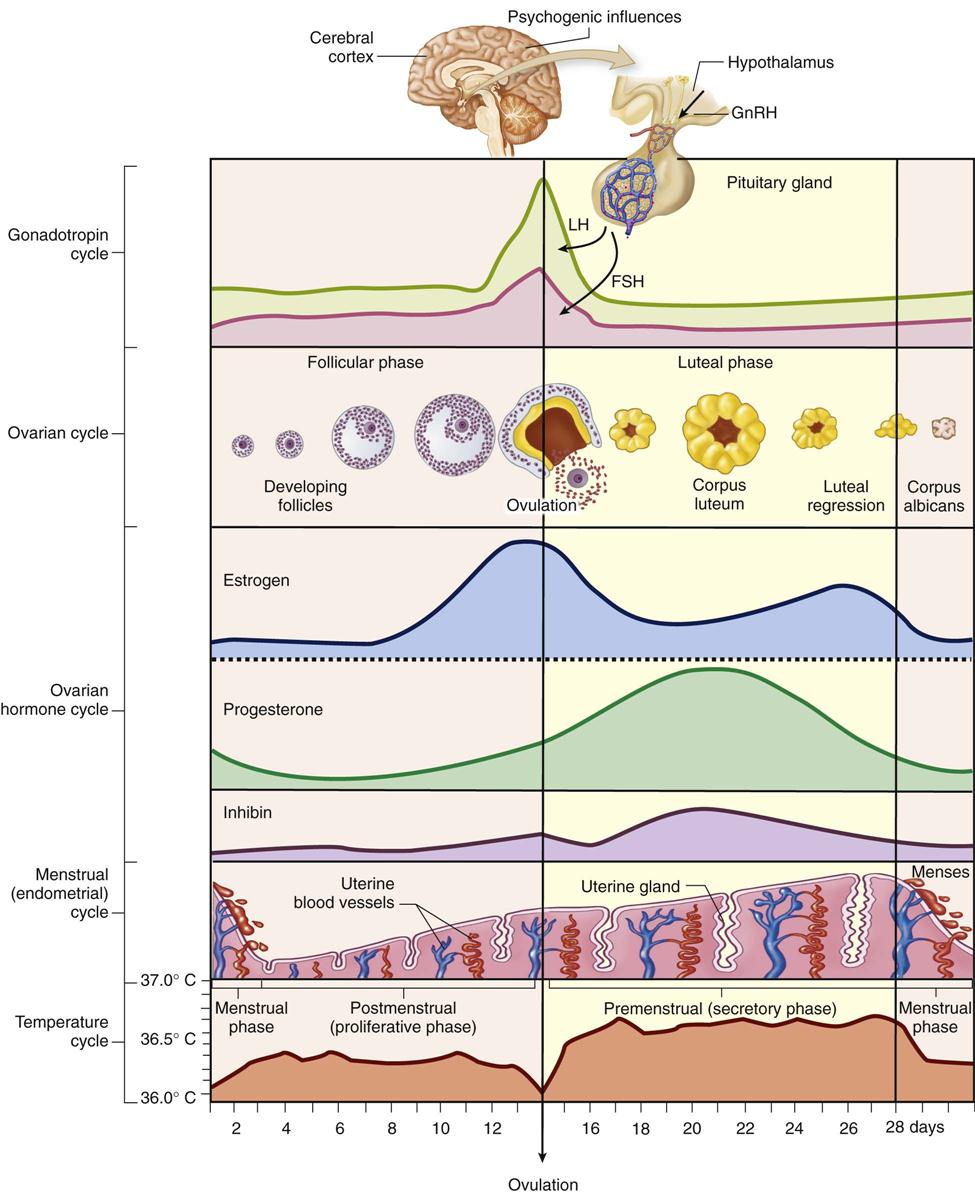

The female gonads are the ovaries, which produce the ova, one each month during the reproductive years between menarche (onset) and menopause. The two ovaries are suspended by ligaments, one on either side of the uterus. These ovaries supply the female gamete, the ovum, and the sex hormones for the female, primarily estrogen and progesterone, on a cyclic basis (Fig. 19-9).

This diagram illustrates the interrelationships among the cerebral, hypothalamic, pituitary, ovarian, and uterine functions throughout a standard 28-day menstrual cycle. The variations in basal body temperature are also illustrated. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy & Physiology, ed 8, St. Louis, 2013, Mosby.)

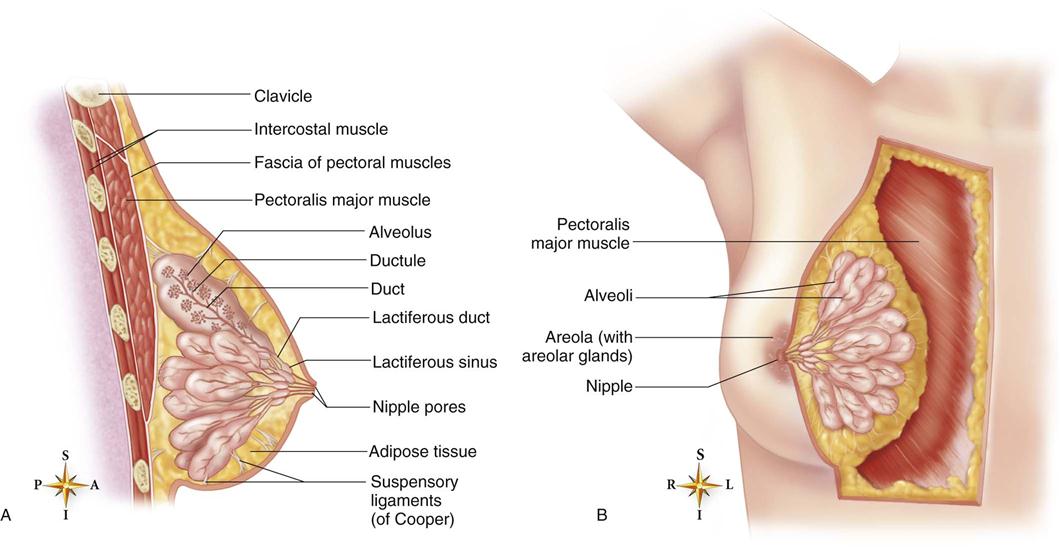

The female breast plays a significant role in the reproductive system. It responds to cyclic hormonal changes and is responsible for lactation, the provision of breast milk to the newborn. Mammary tissue develops under the influence of increased estrogen secretion, commencing at puberty. The breast consists of 15 to 20 lobes supported by ligaments. Muscle and fatty tissue are interspersed among the lobes and their subunits, the lobules and the acini. The acini are the basic functional units of the breast tissue, consisting of epithelial cells that secrete milk and contracting cells that move the milk into ducts. The breast tissue also has a system of collecting and ejecting ducts for milk that culminate in openings in the nipple. The breast is well supplied with blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. Sebaceous glands are found in the areola, the pigmented tissue surrounding the nipple (Fig. 19-10).

A, Sagittal section of a lactating breast. Notice how the glandular structures are anchored to the overlying skin and to the pectoral muscles by the suspensory ligaments of Cooper. Each lobule of glandular tissue is drained by a lactiferous duct that eventually opens through the nipple. B, Anterior view of a lactating breast. Overlying skin and connective tissue have been removed from the medial side to show the internal structure of the breast and underlying skeletal muscle. In nonlactating breasts, the glandular tissue is much less prominent, with adipose tissue making up most of each breast. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy & Physiology, ed 8, St. Louis, 2013, Mosby.)

During the menstrual cycle, the higher estrogen and progesterone levels increase both the vascularity of the breast and the proliferation and dilation of the ducts, leading to increased fullness and tenderness of the breasts premenstrually. It is recommended that breast self-examination be performed shortly after the conclusion of menses, when hormone levels are low and the breasts are small and less nodular. This examination should be performed at the same time each month to allow comparison of the normal characteristics of the breast. Postmenopausally, examination should be done at regular intervals such as the day of the month the woman’s birthday falls on.

Hormones and the Menstrual Cycle

Hormonal secretions, release of ova, and associated endometrial changes occur in a cyclic pattern in women during the reproductive years (see Fig. 19-9). The average cycle is 28 days, but a range of 21 to 45 days is considered normal. Some women experience irregular cycles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree