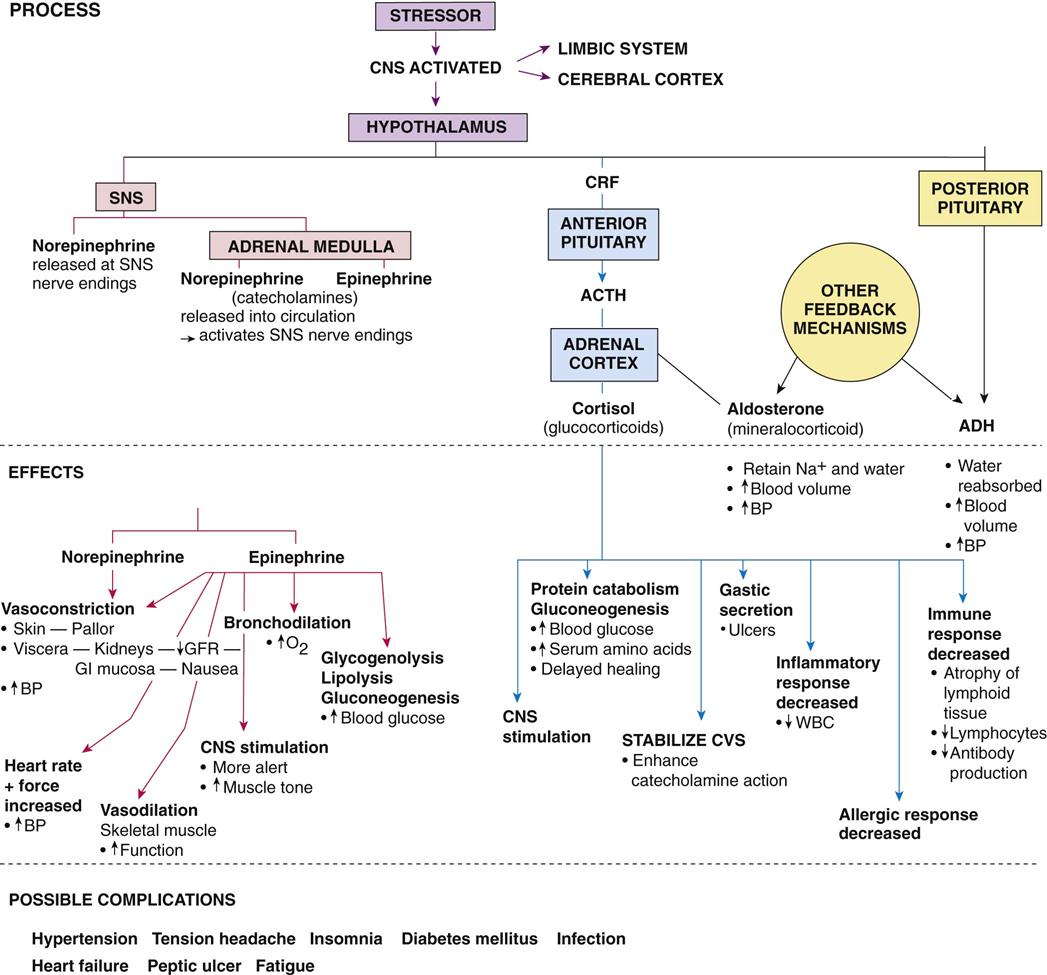

After studying this chapter, the student is expected to: 1. Describe the stress response. 2. Explain how the stress response is related to diseases. 3. Describe how severe stress may lead to acute renal failure, stress ulcers, or infection. bronchodilation endorphins homeostasis lipolysis maladaptive physiologic The stress response is a generalized or systemic response to a change (stressor), internal or external, and may be modified in specific situations. The role of stress in disease became more firmly established in the 20th century, when Hans Selye, in 1946, defined his general adaptation syndrome (GAS), or “fight or flight” concept. His work revealed that the body constantly responds to minor changes in its needs or environment, such as altered food intake or activity level, and thus maintains homeostasis. The body has built-in mechanisms that quickly compensate for physiologic changes in fluid balance or blood pressure. Minor fluctuations in body functions are normal. A stressor is any factor that creates a significant change in the body or environment. It may be physical or psychological or a combination of the two. A stressor may be a real or anticipated factor, or it may be a short-term or long-term factor. Possible stressors include pain, exposure to cold temperatures, trauma, anxiety or fear, a new job, infection, or indeed, even a joyous occasion. Stress is considered to occur when an individual’s status is altered by his or her reaction to a stressor. The stress response is the generic but complex response made by the body to any stressor. The body’s physiologic response to different types of stressors is the same, although the response may vary in intensity and effects in a given situation or person. An additional, specific response may occur with certain stressors; for example, infection may initiate a fever. Each person may perceive stressors differently. A certain stressor for one individual may be mildly exciting or stimulating, but for someone else the same stressor may be deeply depressing. It may even cause illness in another person. If the individual can cope with the stressor, the body returns to its normal status, but if the person cannot adapt, harmful effects may result from the stress. This may be termed “distress.” Stressors are a normal component of life and can be a positive influence on the body when appropriate coping mechanisms function well. Stressors may stimulate growth and development in many ways. Without any changes or stressors in life, a person would merely exist in a dull, inert, unresponsive form. But if a stressor is extremely severe or is perceived as a very negative influence, or when multiple factors effect change at one time, the body’s adaptive mechanisms may not suffice. Then the body systems become more disrupted, maladaptive or inappropriate behavior can occur, and homeostasis is not possible for that person. Factors such as aging or pathologic disorders may interfere with an individual’s ability to respond adequately to a stressor. A vicious cycle may develop when the original stressor remains, and the effects of this stressor prevent the body from coping with new stressors. In some cases, more damage results, adding to the stress and lessening the person’s coping capabilities even further, thereby decreasing the probability of a return to normal status. In the same way, maladaptive behaviors such as ignoring the stressor or eating unwisely are likely to add additional problems without removing the original stressful factor. Selye originally defined three stages in the stress response (GAS). In the alarm stage, the body’s defenses are mobilized by activation of the hypothalamus, sympathetic nervous system, and adrenal glands. In the second, or resistance stage, hormonal levels are elevated, and essential body systems operate at peak performance. The final stage, or stage of exhaustion, occurs when the body is unable to respond further or is damaged by the increased demands. Extensive research into various aspects of stress has followed Selye’s work. It has been found that the stress response involves an integrated series of actions, including the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, the sympathetic nervous system, the adrenal medulla, and the adrenal cortex. The locus ceruleus, a collection of norepinephrine-secreting cells in the brain stem, provides the rapid response in the nervous system. Any type of stressor immediately initiates a marked increase in ACTH secretion followed by a great increase in cortisol secretion. The major actions are summarized in Figure 26-1. Significant effects of the stress response include: • Elevated blood pressure and increased heart rate • Bronchodilation and increased ventilation • Arousal of the central nervous system • Decreased inflammatory and immune responses (cortisol reduces the early and later stages) These activities increase the general level of function in critical areas of the body such as the brain, the heart, and the skeletal muscles by such mechanisms as increasing oxygen levels, increasing circulation, and increasing the rate of cell metabolism. Short-term stressors, mild or moderate, appear to enhance cognitive function and short-term memory. The stress response also results in an increased release of endorphins, which act as pain-blocking agents (see Chapter 4). In most cases, the body responds positively, the stressor is dealt with, the stress response diminishes, and body activity returns to normal. Additional distress results if the state of stress is severe or prolonged, or if the individual’s adaptive mechanisms are impaired for some reason. It may be noticed that when an illness requires additional treatment, such as hospitalization or physiotherapy, extra stressors are added that may overwhelm the patient. For example, hospitalization may give rise to fear and pain or to anxiety associated with separation from the family or job, change in routine and diet, and loss of privacy and control over one’s life. In other cases, hospitalization may offer positive relief from the burden of illness. With major or prolonged stress, intellectual function and memory are frequently disrupted. One factor related to the change is the large amount of glucocorticoids released because memory impairment has been shown to occur in persons taking large doses of glucocorticoids.

Stress and Associated Problems

Learning Objectives

Key Terms

Review of the Stress Response

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine