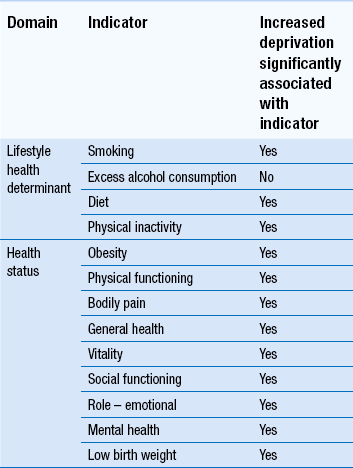

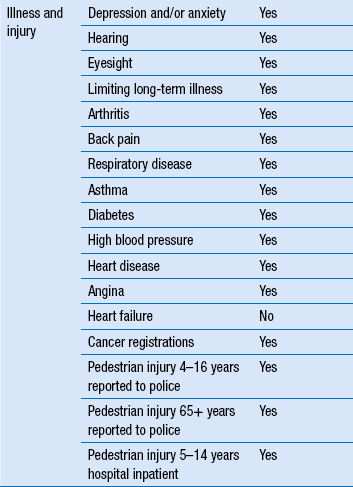

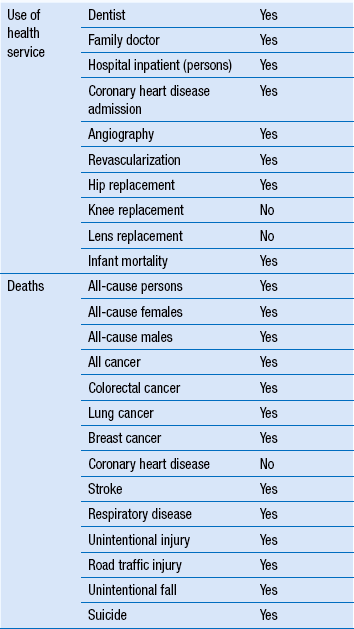

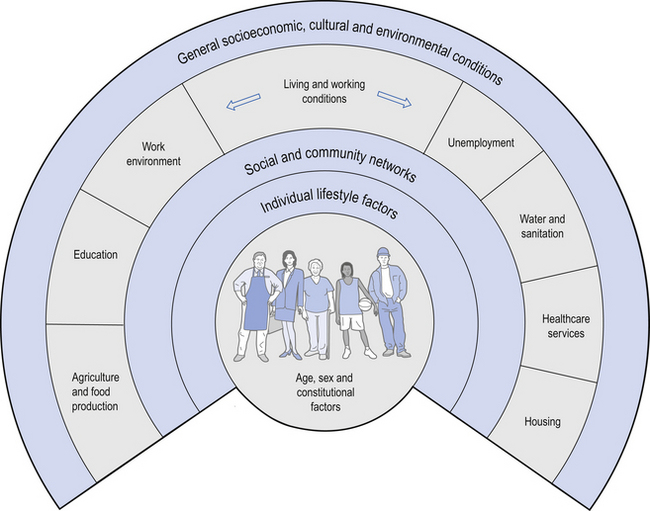

13 While pharmacists have increasingly received wide recognition for their considerable knowledge, skills and expertise in working with patients to resolve medicines-related issues, they appear to have struggled with the concept of contributing to the wider public health agenda. This is ironic, given that for many years pharmacists have addressed a range of public health issues by giving lifestyle advice, among other services, to the populations they serve on topics such as smoking cessation, diet, substance misuse, sexual health, alcohol and exercise. Central to this definition is the concept that promoting public health is not solely an application of evidence-based science, such as epidemiology. For those working in public health, there is also a need to understand different sociological groupings within society and work with others to support and encourage the population or particular sectors of society to make changes that are likely to bring health benefits. To achieve this, those employed in public health typically work across organizations such as local health service bodies, local authorities and local communities in settings that range from acute hospital trusts and local health organizations to local authorities, social services and the voluntary sector. Much of the work is long term and it may take several years before any outcomes materialize that can have a lasting impact on health. Indeed, this could be viewed as being a ‘health service’, in contrast to the current healthcare system that may more closely resemble an ‘ill health service’. This is because resources are used to encourage people to adopt a healthy lifestyle and protect them from communicable diseases, rather than being primarily targeted at people who are ill. Pharmacy should always be in a position to make an impact on public health, even if it restricts its contribution to medicines-related issues. However, to make an optimal contribution to public health, pharmacy needs to also influence the wider determinants of health. This is more challenging and requires an appreciation that more than 70% of the factors that determine a person’s health lie outside of the domain of health services and instead in their demographic, social, economic and environmental conditions. For example, there is limited opportunity to help a patient with asthma improve their health by advising them on the correct use of their inhaler when wider public health issues also influence treatment outcome. The patient may live in poorly heated, damp, infested accommodation, have a low paid job that involves working in a dusty or dirty environment, be poorly educated, have few or no friends or family to support them and have poor mental health. In addition, they may continue to smoke cigarettes, take little exercise and eat too many foods with a high fat content. It is clear that these factors will impact on good disease management, but the influential factors are often much less obvious than described above. Being aware of the wider determinants of health is important, as each carries a significant health burden, many of which are linked to deprivation. A number of these are summarized in Table 13.1. The landmark work of Dahlgren and Whitehead in 1991 highlighted the main factors that determine the health of a given population (Fig. 13.1). The age, gender and genetic make-up of an individual clearly influence the health potential of that individual, although each is fixed and non-modifiable. Other factors that influence health and which can be modified to have a favourable impact include addressing individual lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet and physical activity. Improving interactions with friends and relatives, and developing mutual support within a community can help sustain health. Other wider influences on health include living and working conditions, food provision, access to essential goods and services, and the overall socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions. There are too many factors to discuss in detail here, but a number of the relevant, key determinants are outlined below. However, the simple message is that, whether attempting to evaluate mortality, morbidity or self-reported health, and regardless of whether it is income, class, house ownership, deprivation, social exclusion or a similar indicator or combination of indicators that is used as the socioeconomic indicator, those who are worse off in society have poorer health. Both employment and unemployment can be associated with adverse effects on health. Job security has also been recognized as important for well-being. The trend towards less secure, short-term employment affects everyone but is a particular problem for less skilled manual workers. Unemployment imposes a number of health burdens on the unemployed and some of these are summarized in Box 13.1.

Public health

The principles of public health

The principles of public health

The concept of public health pharmacy

The concept of public health pharmacy

The determinants of health and lifestyle influences on health

The determinants of health and lifestyle influences on health

Introduction

What is public health pharmacy?

Wider determinants of health

Employment and unemployment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Public health