— Anus: extends from 3 to 4 cm above anal verge and merges with rectum — Rectum: 12 to 18 cm in length — Anal verge: demarcation point from perianal skin to anal skin — Dentate line: demarcation between ectoderm of external squamous epithelium and rectal entodermal mucosa. Anal canal does not contain sebaceous or sweat glands; it is innervated by somatic nerves up to and slightly beyond dentate line; it is sensitive to pain. Above the dentate line, rectal mucosa is relatively insensitive to pain but registers distention and inflammation as diffuse visceral pain. — Anorectal line: point above which rectum expands outward into pelvic bowl. • Rectal columns, anal valves, anal glands, and anal crypts: occupy area between dentate and anorectal lines. Anal glands provide mucus to lubricate passage of stool and empty into anal crypts. This area is the locus of anal fistula or perirectal abscess if crypt becomes impacted, unable to discharge mucus. Anal fissures lie below the dentate line. Midway between dentate and anorectal lines lies the white line of Hilton, or pectinate line, the location of the intersphincteric groove, the region that lies between internal and external sphincters. The internal sphincter is controlled by the autonomic nervous system; the external sphincter is under somatic or voluntary control. • Vascular supply: inferior mesenteric artery and internal iliac artery; superior, middle and inferior rectal arteries; anastomosis between these branches. Venous return: superior and middle hemorrhoid veins that empty into inferior mesenteric veins and, subsequently, portal vein and internal iliac vein, vena cava, bypassing liver. • Muscles: levator ani muscle forms the floor of the pelvis and helps form the puborectalis sling. The puborectalis sling causes the bowel to change direction as it penetrates the pelvic floor, making passage of stool easier. The sphincter mechanism controls continence. • Innervation of anal canal: pudendal nerves originating from S2, S3, and S4. • Presenting symptoms: pain, tenderness, rectal spasm, bleeding, itching, protrusions, eruptions, discharges, constipation, diarrhea, changes in stool pattern, sacral backache, shooting pains down limbs, cramping and painful menses, urinary disturbances, anemia, prostatitis, restlessness (in children), foreign bodies. Seemingly unrelated symptoms may have their origin in the anorectal tract. • Result of infection of an anal crypt whose distal end lies near the dentate line. Anal glands become infected because of impacted feces. Infection progresses into intersphincteric space but generally does not penetrate beyond the external sphincter. Most anal glands lie posteriorly; thus most abscesses drain from a line posterior to the ischial tuberosities; anterior ones drain radially from points of origin. Rectal fistula or abscess may indicate internal bowel disease: diverticulitis, trauma to area, or immune system incompetence such as HIV. • Weak points of highly vascularized rectal mucosa are anal glands impacted with feces. Surrounding tissue is swollen, red, and painful to touch. If infection remains in the intersphincteric space, rectal pain is seemingly without specific findings. Eliciting pain with pressure on examination provides a clue regarding the source. The patient may have a fever of unknown origin. • Adjacent ischiorectal fossae have fatty tissue that allows distension of the rectum. An abscess can progress in many directions. In true perianal abscess, incision and drainage are contraindicated; bulk of lesion is untouched because of the invasion of underlying tissues and caverns of pus. Unlike other abscesses, do not allow perianal abscesses to come to a head and rupture to avoid excess necrosis of the anal sphincter. • Obtain surgical consult for rectal abscess. Surgery opens the tract, allowing healing by second intention. Localized treatment helps abscess drain if it has ruptured or if patient presents acutely and referral is not immediately possible. Irrigate with herbal antibacterial agents: Hydrastis, Usnea, and Calendula succus in 0.9% saline will help drainage. • Folliculitis with abscess: incise and drain. They do not involve anal canal or ischiorectal fossa. Homeopathics: Calcarea sulphurica, Silicea, Hepar sulphuris, Myristica. Poultices of onion, garlic, or potatoes have drawing action. Also use alternating hot and cold sitz baths. After abscess breaks open or is incised and drained, irrigate with these herbal solutions. • Anal crypts are pockets between grooves formed by rectal columns at their distal point ending at the dentate line. Anal cryptitis, as separate from fistula, is debatable and rare. Symptom: pain worsened by bowel movement (BM). Signs: localized tenderness and redness at dentate line; rectal spasm. Rule out rectal fissure. Chronic cases suggest bacterial infection of gonorrhea. • Treatment: herbal suppository, sitz baths, increased dietary fiber, local anesthesia as needed. Clean crypt with crypt hook if needed; irrigate with solution of Calendula succus and Hydrastis in normal saline. • Anal fissure: slitlike separation of anal mucosa that lies below the dentate line. Majority (70%-80%) are in the posterior midline region; anterior midline lesions (10%-20%) are more common in women. Oval anal sphincter (rather than round), coming to a Y or narrow point at posterior midline, predisposes to fissure. Anal fissure also occurs in children with chronic diarrhea or hard stool. Fissure may also arise from congenital anal deformity. Lesions in anteroposterior vertical axis suggest internal bowel disease—Crohn’s disease, squamous cell or adenocarcinoma of rectum, syphilitic fissure, and ulceration of tuberculosis (TB). • Very painful from the somatic innervation of spasm of the anal sphincter induced by stretching during BM. Anal fissure triggers vicious cycle—pain causing sphincter spasm with tightening of sphincter and increased pain with BM. Symptoms: severe pain during and after BM and bleeding. As lesion enlarges it may ulcerate and become infected. Conventional treatment: rectal dilation, internal sphincterotomy, electrodessication, or surgical excision. • Causes: passage of large, hard stools; childbirth trauma; chronic diarrhea; trauma; food allergy; prolonged straining to pass stool. High risk: Infants and young children ingesting large amounts of cow’s milk, with chronic constipation, especially if breastfed only a short time. Personality traits: intense, compulsive. Predisposing factors: previous anal or rectal operation, syphilis, Crohn’s disease. • Examination: difficult because of pain and spasm; anoscopic examination requires anesthesia. Local injection of 1% or 2% lidocaine into rectal sphincter at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions relaxes it enough for examination. Fissures are visible without anoscope; pull back anal skin and examine tissue. Sentinel pile or enlarged papillae suggest chronic anal fissure. Anal stenosis and fibrosis indicate chronic state. • Differential diagnosis: Crohn’s disease, especially if patient is younger, has history of periodic or chronic diarrhea, and fissure lies in anteroposterior vertical axis; squamous cell carcinoma; syphilitic ulcers; rarely TB. Spasm of levator ani muscle has no lesion. • Treatment is challenging. Surgery removes the lesion and alleviates pain, but lesion will return if underlying cause is unre-solved. Surgery predisposes to fecal incontinence later in life. Educate patient that healing will have exacerbations and re-missions. • Initial treatment: alleviate pain and spasm. Homeopathics: promptly relieve if simillimum is found; aid healing process. Remedies: Chamomilla, graphite, nitric acid, Ratanhia, Sepia, Silicea thuja. Dose frequently. Protease 2500 μU, 2 capsules t.i.d. between meals and before bed, alleviates pain. Use preparation of 0.2% glycerol trinitrate topically to relieve rectal spasm and 5% lidocaine cream for local pain. Glycerol trinitrate relieves rectal spasm and increases blood flow to sphincter. (Decreased sphincter blood flow may be a precipitating mechanism of fissure.) • Topical cream of vitamins A and E, panthenol, calendula, and comfrey enhances healing by nourishing tissues. Some of the commercial preparations contain boric acid for a styptic effect. Apply cream topically after every BM and at bedtime. As healing occurs, twice-daily administration suffices until lesion resolves. • Iontophoresis: use zinc electrode and apply positive current to facilitate healing by hardening underlying fissure, decreasing bleeding, and relieving pain. Patient lies on negative dispersing pad and current is applied for 10 minutes at 10 mA. • Patient should avoid straining during BM and use cotton balls moistened with water, rather than toilet paper or chemical or alcohol wipes; avoid wiping deep into anal canal. • Sitz baths increase blood flow. Alternative: spray hot and cold water on perineal area. • Increase dietary fiber if condition is caused by chronic constipation. If chronic diarrhea, identify cause. Diet changes are mandatory in irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, and so forth. Higher rates of hemorrhoids and Crohn’s disease occur with blood group O because of food intolerance. • Frequent follow-up: assess healing; reassure patient. After healing, maintain proper bowel function and good dietary habits. • Begin to develop during the 20s; symptoms manifest in the 30s. Fifty percent of persons older than 50 years have symptomatic hemorrhoids; one third of total U.S. population have hemorrhoids to some degree. • Causes: genetics, excessive venous pressure, pregnancy, long periods of standing or sitting, straining at stool, heavy lifting, portal vein lacking valves. Factors increasing venous congestion in perianal region can precipitate hemorrhoids: increasing in-traabdominal pressure (e.g., defecation, pregnancy, coughing, sneezing, vomiting, physical exertion, and portal hypertension from cirrhosis), straining during BM, and standing or sitting for prolonged periods. • Presenting symptoms: itching, burning, irritation with BM, swelling of anus and perianal region, blood on toilet paper or in bowl, seepage of mucus. Rarely are internal hemorrhoids painful or itchy. Hallmark of hemorrhoids: bleeding or protrusion after passing stool. Pain of internal hemorrhoids occurs with strangulation from prolapse and thrombosis. Other pain is from a coexisting lesion, such as a fissure. Itching is rare with internal hemorrhoids except with excess mucus. • Originate above anorectal line in the right anterior, right posterior, and left lateral quadrants. Other areas have secondary hemorrhoids. Occasionally internal hemorrhoid enlarges enough to prolapse below anal sphincter. • Classified by symptoms and examination findings. Stage I: bleed but do not protrude. Stage II: protrude after BM; spontaneously reduce. Stage III: protrude with BM; must be manually reduced. Stage IV: protrude; not reducible. Stages II, III, and IV may or may not bleed. Stage IV: possible strangulation with decreased blood flow and thrombosis. • Internal-external, or mixed hemorrhoids: combination of contiguous external and internal hemorrhoids that appear as baggy swellings. Treating internal hemorrhoid may resolve external portion. If patient has external hemorrhoids, internal ones are probably present. • Hemorrhoids are rare in cultures with high-fiber, unrefined diets. Low-fiber diet leads to strain during BMs because of smaller, harder stools. Straining increases abdominal pressure, obstructing venous return, increasing pelvic congestion, and weakening veins.

Proctologic Conditions

Anorectal anatomy

ANAL DISEASES

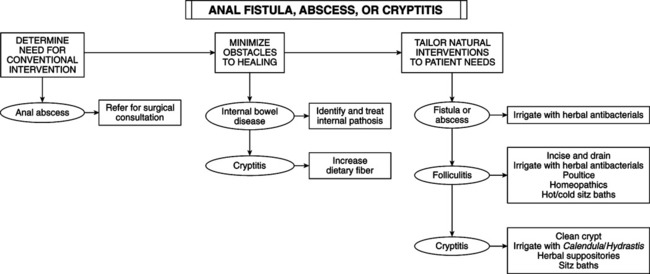

Anal Fistula and Anal Abscess

Anal Cryptitis

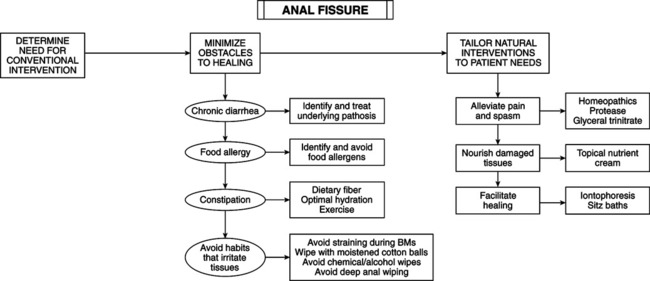

Anal Fissure

Hemorrhoids

Internal Hemorrhoids

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Proctologic Conditions