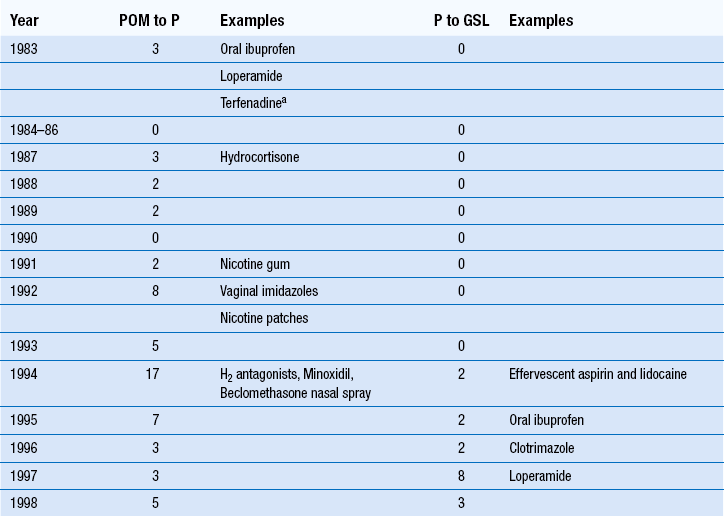

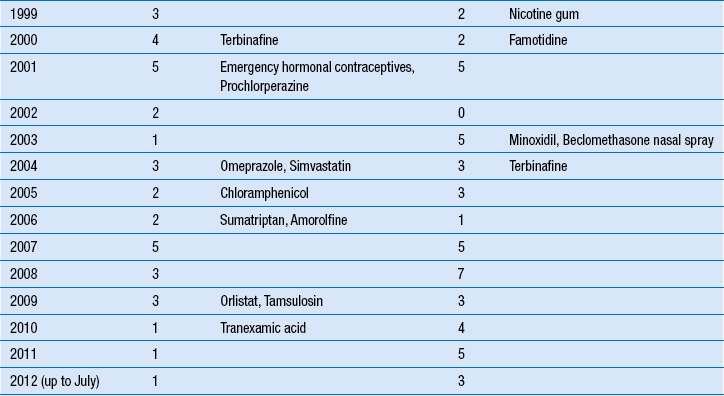

21 The community pharmacist plays an essential role in providing patient care. In most western countries, a network of pharmacies allows patients easy and direct access to a pharmacist without an appointment. Without pharmacists, general medical services would be unable to cope with patient demand. In effect, pharmacists perform a vital triage role for doctors by filtering those patients who can be managed with appropriate advice and medicines and referring cases which require further investigation. This has been a central role of community pharmacists for many decades, but over the last 20 years the role has taken on greater significance as there has been a shift in global healthcare policy to empower patients to exercise self-care. For pharmacists to safely, effectively and competently manage minor ailments requires considerable knowledge and skill. It involves having the underpinning knowledge on diseases and their clinical signs and symptoms, the ability to apply this knowledge to an individual patient and use problem solving to arrive at a working differential diagnosis. This has to be combined with good interpersonal skills such as picking up on non-verbal cues, asking appropriate questions and articulating clearly any advice which is given (see Ch. 25). This chapter attempts to provide the contextual framework behind the growing prominence of the pharmacist in managing minor ailments and the key skills required to maximize performance. The creation of national healthcare schemes, such as the NHS has encouraged the general population to become more reliant on institutional bodies to look after their health. This has led to increased demand on services provided by these bodies, including the management of minor illness. For example, more than one in three GP consultations are for minor illnesses and an estimated 20–40% of GP time could be saved if patients exercised self-care. Similar findings have been recorded for patients attending hospital emergency departments. This dependence by patients on bodies such as the NHS has led to government policies which encourage and facilitate self-care. In the UK, the government agenda for modernizing the NHS was spelt out in its White Paper-The NHS Plan (2000). Within this document, the government made its intention clear to make self-care an important part of NHS health care. It stated that the front line of health care was in the home. Since that time the government has published numerous papers detailing why and how maximizing self-care can be achieved. Less obvious, but arguably more important, has been the expansion of medicines available without prescription (Table 21.1). This has direct impact on community pharmacists and represents one of the major ways in which pharmacy can contribute to self-care. The switching of POMs to P status is now well established. Loperamide and ibuprofen were the first POMs to be switched in 1983. Between 1983 and 2012, over 80 POM to P and 50 P to GSL switches were made. Recent POM to P switches have seen new therapeutic classes deregulated (e.g. proton pump inhibitors, triptans, alpha-blockers) although the number of products switched has slowed. This is in contrast to P to GSL deregulation where the number of switches has steadily increased. This has led to the current situation where most medicines are now GSL and freely available from all retail outlets. The aim of any patient consultation is to determine a diagnosis from the presenting signs and symptoms. In some instances, a specific diagnosis can be determined as the set of signs and symptoms the patient has point very clearly to only one cause. However, in many cases the exact cause can be hard to determine and a ‘differential diagnosis’ will be made. In other words there is a degree of uncertainty with the diagnosis and the practitioner will make a treatment plan based on what they think is the most likely cause. For example, someone who presents with acute cough is likely to have a viral self-limiting cough but it could possibly be bacterial in origin. Advice and treatment might well be the same but an exact diagnosis cannot be made. Open questions are not without their problems. Some patients when asked an open question will provide irrelevant information and it can be difficult to pick up on the important information that is mixed in with irrelevant facts. An active listening approach is required (see Chs 17 and 25). In most consultations a mixture of closed and open questions will be needed.

Prescribing for minor ailments

The growth of self-care and the increase in access to medicines

The growth of self-care and the increase in access to medicines

Gaining information from patients who present at the pharmacy with symptoms or conditions

Gaining information from patients who present at the pharmacy with symptoms or conditions

Use of clinical reasoning to aid differential diagnosis and not an acronym-based approach

Use of clinical reasoning to aid differential diagnosis and not an acronym-based approach

Assessment of patient’s symptoms in order to provide treatment and/or advice for minor ailments

Assessment of patient’s symptoms in order to provide treatment and/or advice for minor ailments

Introduction

The concept and growth of self-care

Government policy

Deregulation of medicines

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Knowledge

Most Likely – Bacterial or allergic conjunctivitis

Most Likely – Bacterial or allergic conjunctivitis

Likely – Viral conjunctivitis, sub-conjunctival haemorrhage

Likely – Viral conjunctivitis, sub-conjunctival haemorrhage

Unlikely – Episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, uveitis

Unlikely – Episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, uveitis

Questioning

Use of open and closed questions

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree