36

Pelvic Girdle

The pelvic girdle is an attachment point for the vertebral column and lower limbs (Fig. 36.1). It is also involved in balance and weight transfer by transmitting the weight of the head and neck, trunk, and upper limbs to both lower limbs.

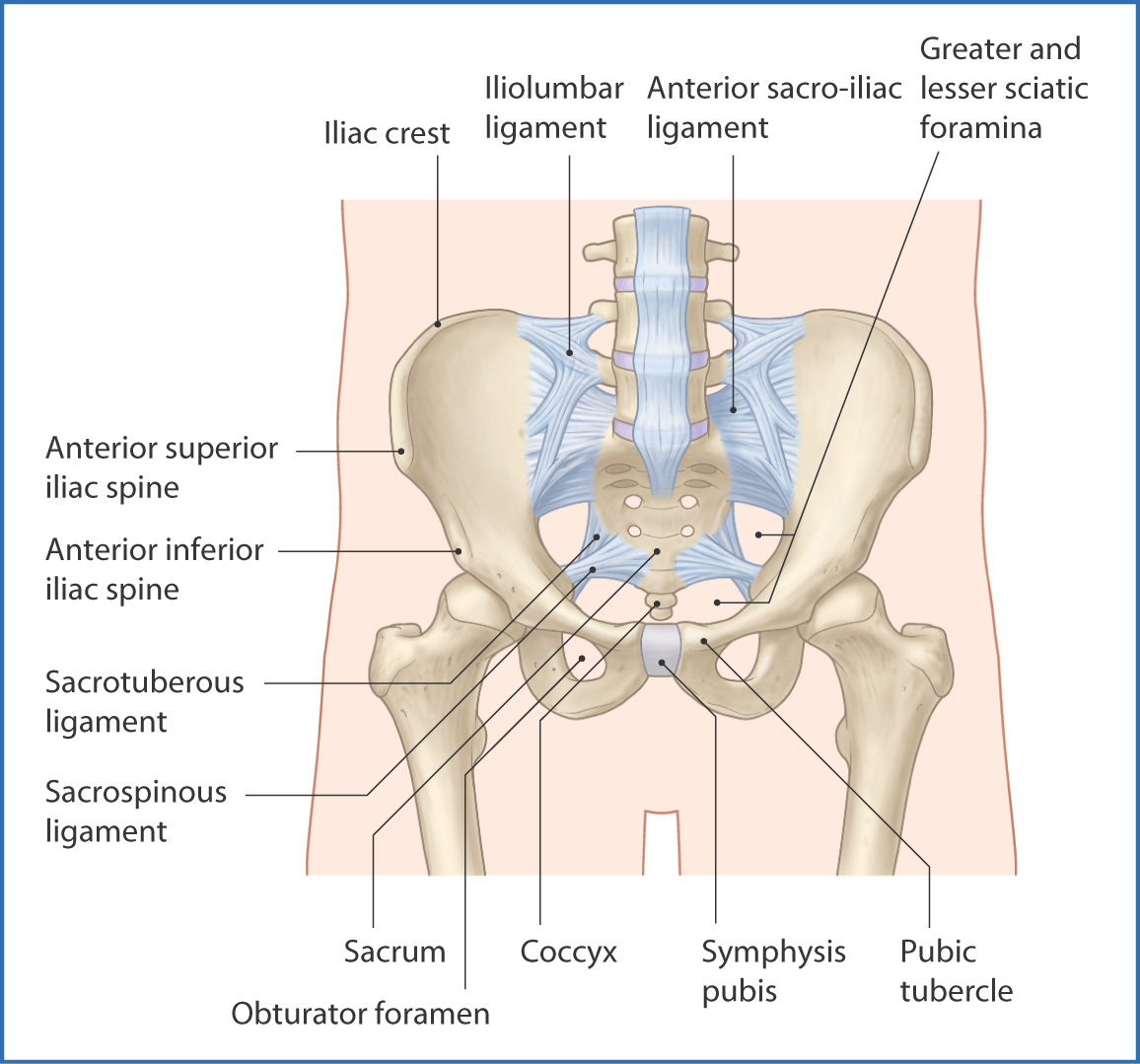

FIGURE 36.1 Pelvis—anterior view.

The left and right sides of the pelvic girdle are identical and are composed of two hip bones, which are formed by fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis.

- The ilium forms the large superior part of the hip bone and has a body and an ala (wing). The superior part of the ala forms a crest (the iliac crest), which is palpable in most individuals.

- The pubis forms the anterior part of the pelvic girdle and has a body and superior and inferior rami. The two pubis bones are joined in the midline by the pubic symphysis, a joint at which movement is slight but nevertheless is of assistance during childbirth.

- The ischium forms the inferior part of the pelvic girdle and has a body, ramus, and large ischial tuberosity, the “sitting bone.”

- The pubis forms the anterior part of the pelvic girdle and has a body and superior and inferior rami. The two pubis bones are joined in the midline by the pubic symphysis, a joint at which movement is slight but nevertheless is of assistance during childbirth.

The sacrum is in the midline of the posterior pelvic girdle. This triangular bone has multiple foramina for the sacral nerves to pass through. It unites the posterior pelvic girdle via the sacro-iliac joints.

At the inferior margin of the sacrum is the coccyx, which is made up of small, usually fused bones.

The sacrococcygeal joint is a cartilaginous joint between the sacrum and coccyx. It is heavily reinforced by ligaments on its anterior, lateral, and posterior surfaces. The sacrum and coccyx stabilize the pelvis and provide attachment points for the ligaments and muscles of the pelvis, lower part of the back (see Chapter 28), and thigh (see Chapters 40 and 42).

On the lateral surface of the pelvic girdle is the acetabulum—a cup-shaped depression where the head of the femur articulates with the pelvic girdle.

Two major ligaments join the sacrum to the ilium and ischium:

- The sacrospinous ligament extends from the sacrum to the ischial spine and forms the lesser sciatic foramen.

- The sacrotuberous ligament extends from the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity and forms the greater sciatic foramen.

Neurovascular structures from within the pelvic girdle pass through the greater and lesser sciatic foramina to the gluteal region, posterior compartment of the thigh, and perineum:

- The piriformis muscle, sciatic nerve, inferior gluteal nerve and artery, internal pudendal nerve, artery, and vein, nerve to the quadratus femoris, nerve to the obturator internus, and posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh pass through the greater sciatic foramen.

- The tendon of the obturator internus muscle, nerve to the obturator internus, pudendal nerve, and internal pudendal artery pass through the lesser sciatic foramen.

The obturator foramen is inferior to the acetabulum (see Fig. 36.1), and most of it is closed by a membrane of flat connective tissue, the obturator membrane.

Muscles

The pelvic girdle is lined by muscles that support the trunk and move the lower limbs. These muscles are described in Chapters 28, 35, 40, and 42. The pelvic girdle does not have any mobile joints, so there are no intrinsic muscles (muscles that move pelvic bones). However, several muscles span different parts of the pelvis and support the pelvic viscera and perineum (see Chapter 38).

The muscles of the pelvis are described according to their location. The obturator internus muscle covers part of the lateral pelvic wall. It passes from the internal surface of the obturator membrane of the pelvis, and its fibers converge to form a tendon that leaves the pelvis laterally through the lesser sciatic foramen, inserts onto the greater trochanter of the femur, and assists in lateral rotation of the thigh.

The posterior pelvic wall is partly covered by the piriformis muscle. This muscle originates from the anterior surface of the sacrum, extends laterally through the greater sciatic foramen to insert onto the greater trochanter of the femur, and rotates the femur laterally. The nerves of the sacral plexus are medial to the origin of the piriformis.

The pelvic diaphragm (pelvic floor) is formed from the levator ani and coccygeus muscles (see Chapter 38).

Nerves

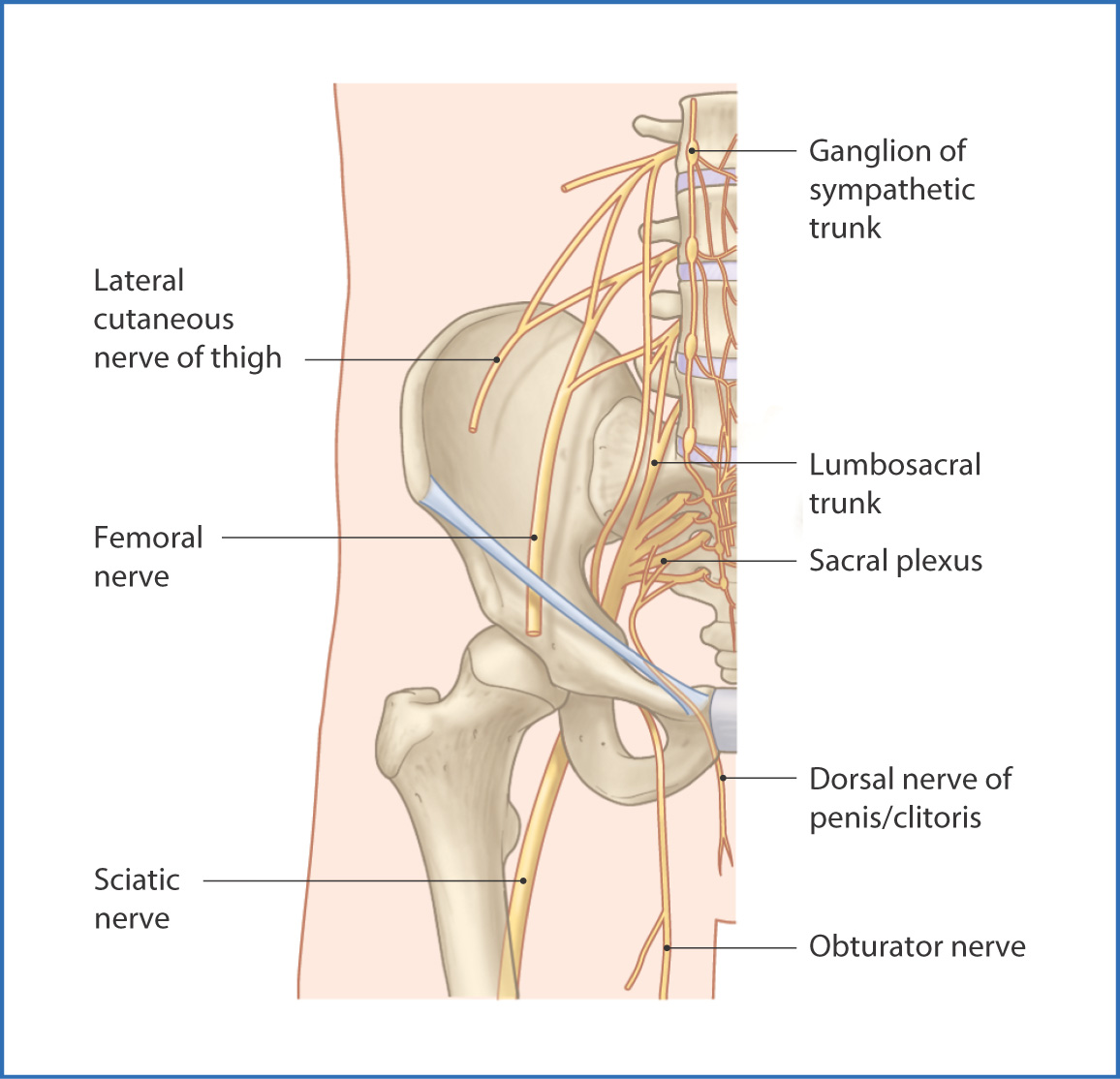

The nerve supply to the pelvis is provided by voluntary (somatic) and involuntary (autonomic) nerves (Fig. 36.2). The somatic nerves are branches of the sacral plexus of nerves, which is formed by joining of the L4 and L5 lumbar spinal nerves (lumbosacral trunk) and the sacral spinal nerves S1 to S4. Nerve fibers from this plexus intertwine in various combinations to form the following nerves:

- The superior gluteal nerve (L4 to S1) exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, enters the gluteal region, and innervates the gluteus medius and minimus muscles, as well as the tensor fasciae latae muscle.

- The inferior gluteal nerve (L5 to S2) exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen to innervate the gluteus maximus muscle.

- The sciatic nerve (L4 to S3), the largest nerve in the body, leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen to innervate all structures of the posterior compartment of the thigh, leg, ankle, and foot (except for a small area of skin on the anteromedial part of the leg, which is supplied by the femoral nerve).

- The nerve to the obturator internus (L5 to S2) leaves the pelvis medial to the sciatic nerve and enters the gluteal region to innervate the obturator internus and superior gemellus muscles.

- The nerve to the quadratus femoris (L5 to S1) leaves the pelvis anterior to the sciatic nerve via the greater sciatic foramen. It supplies an articular branch to the hip joint and a muscular branch to the inferior gemellus muscle before terminating at the quadratus femoris muscle.

- The pudendal nerve (S2 to S4) leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen and is medial to the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh in the gluteal region—from here, it turns medially and passes through the lesser sciatic notch to innervate structures of the ischiorectal fossa and perineum (see Chapter 38).

- The inferior gluteal nerve (L5 to S2) exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen to innervate the gluteus maximus muscle.

FIGURE 36.2 Nerves of the pelvis—anterior view.

Several other nerves that originate from the sacral plexus do not leave the pelvis. These nerves are the nerve to the piriformis muscle, sacral branches to the levator ani muscles, coccygeal nerve, and inferior anal nerves.

The pelvic splanchnic nerves

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree