Assessment and Ongoing Evaluation

Assessment is the foundation of treatment. In the absence of thorough assessment, effective pain management is impossible. Assessment begins with a comprehensive evaluation and then continues with regular follow-up evaluations. The initial assessment provides the basis for designing the treatment program. Follow-ups let us know how well treatment is working.

Comprehensive Initial Assessment

The initial assessment employs an extensive array of tests. The primary objective is to characterize the pain and identify its cause. This information provides the basis for designing a pain management plan. In addition, by documenting the patient’s baseline pain status, the initial assessment provides a basis for evaluating the efficacy of treatment.

Assessment of Pain Intensity and Character: The Patient Self-Report

The patient’s description of his or her pain is the cornerstone of pain assessment. No other component of assessment is more important! Remember, pain is a personal experience. Accordingly, if we want to assess pain, we must rely on the patient to tell us about it. Furthermore, we must act on what the patient says—even if we personally believe the patient may not be telling the truth.

The best way to ensure an accurate report is to ask the right questions and listen carefully to the answers. We cannot elicit comprehensive information by asking, “How do you feel?” Rather, we must ask a series of specific questions. The answers should be recorded on a pain inventory form. The following information should be obtained:

Onset and temporal pattern: When did your pain begin? How often does it occur? Has the intensity increased, decreased, or remained constant? Does the intensity vary throughout the day?

Location: Where is your pain? Do you feel pain in more than one place? Ask patients to point to the exact location of the pain, either on themselves, on you, or on a full-body drawing.

Quality: What does your pain feel like? Is it sharp or dull? Does it ache? Is it shooting or stabbing? Burning or tingling? These questions can help distinguish neuropathic pain from nociceptive pain.

Intensity: On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 the most intense pain you can imagine, how would you rank your pain now? How would you rank your pain at its worst? And at its best? A pain intensity scale (see later) can be very helpful for this assessment.

Modulating factors: What makes your pain worse? What makes it better?

Previous treatment: What treatments have you tried to relieve your pain (e.g., analgesics, acupuncture, relaxation techniques)? Are they effective now? If not, were they ever effective in the past?

Impact: How does the pain affect your ability to function, both physically and socially? For example, does the pain interfere with your general mobility, work, eating, sleeping, socializing, or sex life?

Physical and Neurologic Examinations

The physical and neurologic examinations help to further characterize the pain, identify its source, and identify any complications related to the underlying pathology. The clinician should examine the site of pain and determine whether palpation or manipulation makes it worse. Nonverbal cues (e.g., protecting the painful area, limited movement in an arm or leg) that may indicate pain should be noted. Common patterns of referred pain should be assessed. For example, if the patient has hip pain, the assessment should determine whether the pain actually originates in the hip or if it is referred pain caused by pathology in the lumbar spine. Potential neurologic complications should be considered. For example, patients with back pain should be evaluated for impaired motor and sensory function in the limbs and for impaired rectal and urinary sphincter function, which may indicate spinal cord involvement.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic tests are performed to identify the underlying cause of pain (e.g., progression of cancer, tissue injury caused by cancer treatments). The battery of diagnostic tests includes imaging studies (e.g., computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging), neurophysiologic tests, and tests for tumor markers in blood. To ensure that abnormalities identified in the diagnostic tests really do explain the patient’s pain, these findings should be correlated with findings from the physical and neurologic examinations.

Psychosocial Assessment

Psychosocial assessment is directed at both the patient and his or her family. The information is used in making pain management decisions. Some important issues to address include the following:

• The effect of significant pain on the patient in the past

• The patient’s usual coping responses to pain and stress

• The patient’s preferences regarding pain management methods

• The patient’s concerns about using opioids and other controlled substances (anxiolytics, stimulants)

• Changes in the patient’s mood (anxiety, depression) brought on by cancer and pain

• The effect of cancer and its treatment on the family

• The level of care the family can provide and the potential need for outside help (e.g., hospice)

Ongoing Evaluation

After a treatment plan has been implemented, pain should be reassessed frequently. The objective is to determine the efficacy of treatment and to allow early diagnosis and treatment of new pain. Each time an analgesic drug is administered, pain should be evaluated after sufficient time has elapsed for the drug to take effect. Because most patients are treated at home, patients and caregivers should be taught to conduct and document pain evaluations. The prescriber will use the documented record to make adjustments to the pain management plan.

Prescribers, patients, and caregivers should be alert for new pain. In most cases, new pain results from a new cause (e.g., metastasis, infection, fracture). Accordingly, whenever new pain occurs, a rigorous diagnostic workup is indicated.

Drug Therapy

Analgesic drugs are the most powerful weapons we have for overcoming cancer pain. With proper use, these agents can relieve pain in 90% of patients. Because analgesics are so effective, drug therapy is the principal modality for pain treatment. Three types of analgesics are employed:

• Nonopioid analgesics (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and acetaminophen)

• Opioid analgesics (e.g., oxycodone, fentanyl, morphine)

• Adjuvant analgesics (e.g., amitriptyline, carbamazepine, dextroamphetamine)

These classes differ in their abilities to relieve pain. With the nonopioid and adjuvant analgesics, there is a ceiling to how much relief we can achieve. In contrast, there is no ceiling to relief with the opioids.

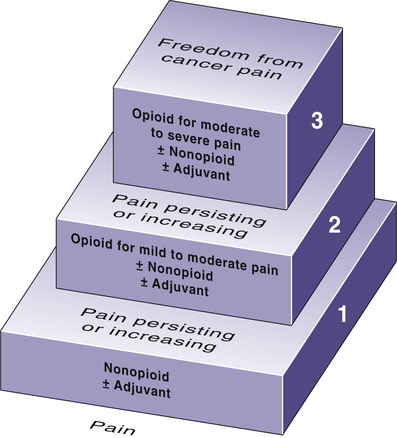

Selection among the analgesics is based on pain intensity and pain type. To help guide drug selection, the World Health Organization (WHO) devised a drug selection ladder (Fig. 83.2). The first step of the ladder—for mild to moderate pain—consists of nonopioid analgesics: NSAIDs and acetaminophen. The second step—for more severe pain—adds opioid analgesics of moderate strength (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone). The top step—for severe pain—substitutes powerful opioids (e.g., morphine, fentanyl) for the weaker ones. Adjuvant analgesics, which are especially effective against neuropathic pain, can be used on any step of the ladder. Specific drugs to avoid are listed in Table 83.1.

TABLE 83.1

Drugs That Are Not Recommended for Treating Cancer Pain

| Drug Class | Drug | Why the Drug Is Not Recommended |

| OPIOIDS | ||

| Pure agonists | Meperidine | A toxic metabolite accumulates with prolonged use |

| Codeine | Maximal pain relief is limited owing to dose-limiting side effects | |

| Agonist-antagonists | Buprenorphine Butorphanol Nalbuphine Pentazocine | Ceiling to analgesic effects; can precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients; cause psychotomimetic reactions |

| Opioid antagonists | Naloxone Naltrexone | Can precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients; limit use to reversing life-threatening respiratory depression caused by opioid overdose |

| Benzodiazepines | Diazepam Lorazepam others | Sedation from benzodiazepines limits opioid dosage; no demonstrated analgesic action |

| Barbiturates | Amobarbital Secobarbital Others | Sedation from barbiturates limits opioid dosage; no demonstrated analgesic action |

| Miscellaneous | Marijuana | Side effects (dysphoria, drowsiness, hypotension, bradycardia) preclude routine use as an analgesic |

Traditionally, patients have been given opioid analgesics only after a trial with nonopioids has failed. Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend a different approach, in which initial drug selection is based on pain intensity. Specifically, if the patient reports pain in the 4 to 10 range, then treatment should start directly with an opioid; an initial trial with a nonopioid is considered unnecessary. If the patient reports pain in the 1 to 3 range, then treatment usually begins with a nonopioid, although starting with an opioid remains an alternative.

It is common practice to combine an opioid with a nonopioid because the combination can be more effective than either drug alone. When pain is only moderate, opioids and nonopioids can be given in a fixed-dose combination formulation, thereby simplifying dosing. However, when pain is severe, these drugs must be given separately because, with a fixed-dose combination, side effects of the nonopioid would become intolerable as the dosage grew large and hence would limit how much opioid could be given.

Drug therapy of cancer pain should adhere to the following principles:

• Perform a comprehensive pretreatment assessment to identify pain intensity and the underlying cause.

• Individualize the treatment plan.

• Use the WHO analgesic ladder and NCCN guidelines to guide drug selection.

• Use oral therapy whenever possible.

• Avoid intramuscular (IM) injections whenever possible.

• For persistent pain, administer analgesics on a fixed schedule around-the-clock (ATC), and provide additional rescue doses of a short-acting agent if breakthrough pain occurs.

• Evaluate the patient frequently for pain relief and drug side effects.

Nonopioid Analgesics

The nonopioid analgesics—NSAIDs and acetaminophen—constitute the first rung of the WHO analgesic ladder. These agents are the initial drugs of choice for patients with mild pain. There is a ceiling to how much pain relief nonopioid drugs can provide, so there is no benefit to exceeding recommended dosages (Table 83.2). Acetaminophen is about equal to the NSAIDs in analgesic efficacy but lacks antiinflammatory actions. Because of this difference and others, acetaminophen is considered separately later. The NSAIDs and acetaminophen are discussed in Chapter 55.

TABLE 83.2

Dosages for Nonopioid Analgesics: Acetaminophen and Selected NSAIDs

| Usual Adult Dosage* | ||

| Drug | Body Weight 50 kg or More | Body Weight Less Than 50 kg |

| Acetaminophen | 650 mg every 4 hr or 975 mg every 6 hr | 10–15 mg/kg every 4 hr or 15–20 mg/kg every 4 hr (rectal) |

| NSAIDS: SALICYLATES | ||

| Aspirin | 650 mg every 4 hr or 975 mg every 6 hr | 10–15 mg/kg every 4 hr or 15–20 mg/kg ever 4 hr (rectal) |

| Magnesium salicylate [Magan]† | 650 mg every 4 hr | — |

| NSAIDS: PROPIONIC ACID DERIVATIVES | ||

| Fenoprofen | 300–600 mg every 6 hr | — |

| Ibuprofen [Motrin, Advil, others] | 400–800 mg every 6 hr | 10 mg/kg every 6–8 hr |

| Ketoprofen | 25–60 mg every 6–8 hr | — |

| Naproxen [Naprosyn] | 250–275 mg every 6–8 hr | 5 mg/kg every 8 hr |

| Naproxen sodium [Anaprox, Aleve, Naprelan, others] | 275 mg every 6–8 hr | — |

| NSAIDS: SELECTIVE COX-2 INHIBITORS | ||

| Celecoxib [Celebrex] | 200 mg every 12 hr | — |

| NSAIDS: MISCELLANEOUS | ||

| Diflunisal | 500 mg every 12 hr | — |

| Etodolac | 200–400 mg every 6–8 hr | — |

| Meclofenamate sodium | 50–100 mg every 6 hr | — |

Mefenamic acid [Ponstel, Ponstan  ] ] | 250 mg every 6 hr | — |

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs (e.g., aspirin, ibuprofen) can produce a variety of effects. Primary beneficial effects are pain relief, suppression of inflammation, and reduction of fever. Primary adverse effects are gastric ulceration, acute renal failure, and bleeding. In addition, all NSAIDs except aspirin increase the risk for thrombotic events (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke). In contrast to opioids, NSAIDs do not cause tolerance, physical dependence, or psychological dependence.

NSAIDs are effective analgesics that can relieve mild to moderate pain. All of the NSAIDs have essentially equal analgesic efficacy, although individual patients may respond better to one NSAID than to another. NSAIDs relieve pain by a mechanism different from that of the opioids. As a result, combined use of an NSAID with an opioid can produce greater pain relief than either agent alone.

NSAIDs produce their effects—both good and bad—by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme that has two forms, known as cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). Most NSAIDs inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2, although a few are selective for COX-2. The selective COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib [Celebrex]) cause less gastrointestinal (GI) damage than the nonselective inhibitors. Unfortunately, the selective inhibitors pose a greater risk for thrombotic events, and hence long-term use of these drugs is not recommended.

For patients undergoing chemotherapy, inhibition of platelet aggregation by NSAIDs is a serious concern. Many anticancer drugs suppress bone marrow function and thereby decrease platelet production. The resultant thrombocytopenia puts patients at risk for bruising and bleeding. Obviously, this risk will be increased by drugs that inhibit platelet function. Among the conventional NSAIDs, only one subclass—the nonacetylated salicylates (e.g., magnesium salicylate)—does not inhibit platelet aggregation and hence is safe for patients with thrombocytopenia. All other conventional NSAIDs should be avoided. Aspirin should be avoided because it causes irreversible inhibition of platelet aggregation. Hence its effects persist for the life of the platelet (about 8 days). Because COX-2 inhibitors do not affect platelets, these drugs are safe for patients with thrombocytopenia.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen [Tylenol, others] is similar to the NSAIDs in some respects and different in others. Like the NSAIDs, acetaminophen is an effective analgesic and hence can relieve mild to moderate pain. Benefits derive from inhibiting COX in the central nervous system (CNS), but not in the periphery. Combining acetaminophen with an opioid can produce greater analgesia than either drug alone (because acetaminophen and opioids relieve pain by different mechanisms).

Acetaminophen differs from the NSAIDs in several important ways. Because it does not inhibit COX in the periphery, acetaminophen lacks antiinflammatory actions, does not inhibit platelet aggregation, and does not promote gastric ulceration, renal failure, or thrombotic events. Because acetaminophen does not affect platelets, the drug is safe for patients with thrombocytopenia.

Acetaminophen has important interactions with two other drugs: alcohol and warfarin (an anticoagulant). Combining acetaminophen with alcohol, even in moderate amounts, can result in potentially fatal liver damage. Accordingly, patients taking acetaminophen should minimize alcohol consumption. Acetaminophen also can increase the risk for bleeding in patients taking warfarin. The mechanism appears to be inhibition of warfarin metabolism, which causes warfarin to accumulate to toxic levels.

Opioid Analgesics

Opioids are the most effective analgesics available and hence are the primary drugs for treating moderate to severe cancer pain. With proper dosing, opioids can safely relieve pain in about 90% of cancer patients. Unfortunately, many patients are denied adequate doses, owing largely to unfounded fears of addiction.

Opioids produce a variety of pharmacologic effects. In addition to analgesia, they can cause sedation, euphoria, constipation, respiratory depression, urinary retention, and miosis. With continuous use, tolerance develops to most of these effects, with the notable exceptions of constipation and miosis. Continuous use also results in physical dependence, which must not be equated with addiction.

The opioids are discussed in Chapter 22. Discussion here focuses on their use in patients with cancer.

Mechanism of Action and Classification

Opioid analgesics relieve pain by mimicking the actions of endogenous opioid peptides (enkephalins, dynorphins, endorphins), primarily at mu receptors and partly at kappa receptors.

Based on their actions at mu and kappa receptors, the opioids fall into two major groups: (1) pure (full) agonists (e.g., morphine) and (2) agonist-antagonists (e.g., butorphanol). The pure agonists can be subdivided into (1) agents for mild to moderate pain and (2) agents for moderate to severe pain. The pure agonists act as agonists at mu receptors and at kappa receptors. In contrast, the agonist-antagonists act as agonists only at kappa receptors; at mu receptors, these drugs act as antagonists. Because their agonist actions are limited to kappa receptors, the agonist-antagonists have a ceiling to their analgesic effects. Furthermore, because of their antagonist actions, the agonist-antagonists can block access of the pure agonists to mu receptors, and can thereby prevent the pure agonists from relieving pain. Accordingly, agonist-antagonists are not recommended for managing cancer pain.

Tolerance and Physical Dependence

Over time, opioids cause tolerance and physical dependence. These phenomena, which are generally inseparable, reflect neuronal adaptations to prolonged opioid exposure. Some degree of tolerance and physical dependence develops after 1 to 2 weeks of opioid use.

Tolerance

Tolerance can be defined as a state in which a specific dose (e.g., 10 mg of morphine) produces a smaller effect than it could when treatment began. Put another way, tolerance is a state in which dosage must be increased to maintain the desired response. In patients with cancer, however, a need for larger doses isn’t always a sign of tolerance. In fact, it’s usually a sign that pain is getting worse (owing to disease progression).

Tolerance develops to some opioid effects but not to others. Tolerance develops to analgesia, euphoria, respiratory depression, and sedation. In contrast, little or no tolerance develops to constipation or miosis.

There is cross-tolerance among opioids. Accordingly, significant tolerance to one opioid confers a similar degree of tolerance to all others.

Physical Dependence

Physical dependence is a state in which an abstinence syndrome will occur if a drug is abruptly withdrawn. With opioids, the abstinence syndrome can be very unpleasant—but not dangerous. The intensity and duration of the abstinence syndrome are determined in part by the duration of drug use and in part by the half-life of the drug taken. Because drugs with a short half-life leave the body rapidly, the abstinence syndrome is brief but intense. Conversely, for drugs with long half-lives, the syndrome is prolonged but relatively mild. The abstinence syndrome can be minimized by withdrawing opioids slowly (i.e., by giving progressively smaller doses over several days). Please note that physical dependence is not the same as addiction!

Addiction

Opioid addiction is an important issue in pain management—not because addiction occurs (it rarely does), but because inappropriate fears of addiction are a major cause for undertreatment.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine defines addiction as a disease process characterized by continued use of a psychoactive substance despite physical, psychological, or social harm. According to this definition, addiction is primarily a behavior pattern—and is not equated with physical dependence. Although it is true that physical dependence can contribute to addictive behavior, other factors—especially psychological dependence—are the primary underlying cause. All cancer patients who take opioids chronically develop substantial physical dependence, but only a few (<1%) develop addictive behavior. Most patients, if their cancer were cured, would simply go through gradual withdrawal and never think about or use opioids again. Clearly, these patients cannot be considered addicted, despite their physical dependence.

Because of misconceptions about opioid addiction, prescribers often order lower doses than patients need, nurses administer lower doses than were ordered, patients report less pain than they actually have, and family members discourage opioid use. The end result? Most cancer patients receive lower doses of opioids than they need. We can improve this unacceptable situation by educating providers, nurses, patients, and family members. Specifically, we must teach them about the nature of addiction and inform them that development of addiction in the therapeutic setting is very rare. Hopefully, this information will dispel unfounded fears of addiction and will thereby help ensure delivery of opioids in doses that are sufficient to relieve suffering.

Drug Selection

Preferred Opioids

For all cancer patients, pure opioid agonists are preferred to the agonist-antagonists. If pain is not too intense, a moderately strong opioid (e.g., oxycodone) is appropriate. If pain is moderate to severe, a strong opioid (e.g., morphine) should be used. Because morphine is inexpensive, available in multiple dosage forms, and clinically well understood, this opioid is used more than any other. Preferred opioids are listed in Table 83.3.

TABLE 83.3

Equianalgesic Doses of Pure Opioid Agonists and Tramadol

| Drug | Equianalgesic Dosea | Duration (Hours)b | |

| Parenteral | Oral | ||

| AGENTS FOR MILD TO MODERATE PAIN | |||

| Codeinec,d | 130 mg | 200 mg | 3–4 |

| Hydrocodonee | NA | 30–45 mg | 3–4 |

| Oxycodonef | NA | 20 mg | 3–4 |

| Tramadolf,g | NA | 50–100 mg | 3–7 |

| AGENTS FOR MODERATE TO SEVERE PAIN | |||

| Morphinec,h | 10 mg | 30 mg | 3–4 |

| Fentanyli,j | 100 mcg | NA | 1–3 |

| Hydromorphonec | 1.5 mg | 7.5 mg | 2–3 |

| Levorphanolk | 2 mg | 4 mg | 3–6 |

| Methadonek,l | Variable | Variable | Variable |

| Oxymorphonef | 1 mg | 10 mg | 3–6 |