16 Paediatric disorders

EMBRYOLOGY

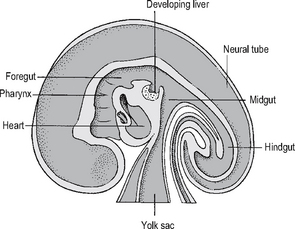

The embryo folds and converts the flat trilaminar disc into a c-shaped cylindrical embryo (Fig. 16.1). The original endoderm has developed into the yolk sac, and part of this is incorporated into the embryo as the gut. As the cranial end of the embryo folds, it takes the mouth and heart ventrally, and incorporates the adjacent yolk sac as the foregut, and the most cranial part of the embryo is then the brain as it develops from the neural plate. As the caudal end of the embryo folds, the adjacent yolk sac is incorporated as the hindgut, and is carried ventrally as the cloaca, allantois and umbilical cord. The embryo also folds horizontally and incorporates part of the yolk sac as the midgut, which in these early stages is outside the embryo, within the umbilical cord. The rest of the yolk sac remains attached to the midgut as a stalk.

Fig. 16.1 Early embryo – sagittal section.

Source: Rogers A W, Textbook of anatomy; Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh (1992).

PERSISTENCE OF THE BRANCHIAL ARCHES AND THEIR REMNANTS

The first arch anomalies include cleft lip and palate (see p. 496). Upper preauricular sinuses and skin tags (which invariably contain cartilage) are usually superficial and can easily be excised, but a low preauricular sinus may have a deep internal connection to the first arch – a surprising finding for the unsuspecting surgeon who follows a track and ends up within the middle ear – and close to the facial nerve, with its consequent problems if damaged.

LINGUAL THYROID AND THYROGLOSSAL CYSTS

The thyroid may fail to descend, and remain as a small gland in the tongue at the site where it started its outgrowth (the foramen caecum, in the midline at the junction of the anterior two-thirds and posterior third of the tongue), or it may partially descend and be mistaken for a thyroglossal cyst – see below. This ‘ectopic’ or incompletely descended thyroid tissue is invariably hypoplastic, and should be removed, as it may suffer from all the pathological problems of a normally sited thyroid. The patient should be investigated to see if they have any normally sited thyroid, which most of them do not. The patient will usually become hypothyroid, as this gland is hypoplastic, and if it is their only thyroid tissue, and it is removed, the patient will certainly become hypothyroid, but without potential problems from the gland.

CLEFT LIP AND PALATE

This is one of the more common congenital anomalies, occurring in 1 in 600 live births.

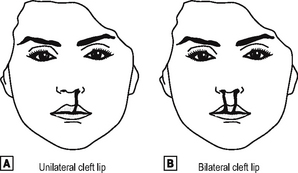

The face forms during the fifth to the eighth week, from the maxillary and mandibular prominences of the first branchial arch. They grow and fuse together, and if this fusion is incomplete, unilateral or bilateral cleft lip may arise (Fig. 16.2).

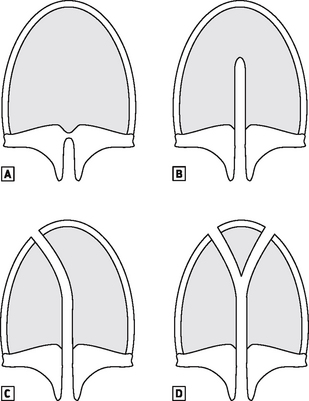

The palate develops after the eighth week, and fusion occurs between the primary palate (the anterior section of the premaxilla and attached four front teeth) and the secondary palate (the hard and soft palate). The palate may be cleft posteriorly only, a cleft soft palate, or it may extend anteriorly to include the hard palate, cleft palate only, and more commonly it extends further anteriorly to join up with either a unilateral or bilateral cleft lip (Fig. 16.3).

CYSTIC HYGROMA (LYMPHANGIOMA)

The primitive lymph sacs develop in the mesenchyme in the sixth week, and the largest is in the neck, and should resolve, but persistence and sequestration produces a multicystic swelling within the neck which is a lymphangioma, a benign hamartoma (overgrowth of normal tissue), which is also called a cystic hygroma when it occurs in the neck. Occasionally this is very large and causes respiratory distress in the neonatal age group, but more usually is just a soft swelling in the neck which may extend into the axilla, or even the chest. A degree of spontaneous resolution can be hoped for, but often it comes to surgical debulking – a difficult prospect because of the multicystic nature, which makes it difficult to be sure that every bit of the abnormal tissue is removed. If there is a haemangiomatous element as well as the lymphangiomatous part, spontaneous resolution is unlikely. An MRI scan is recommended to delineate the full extent and nature of the lesion, and the normal structures which are involved, to help plan surgical excision.

CONGENITAL DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA

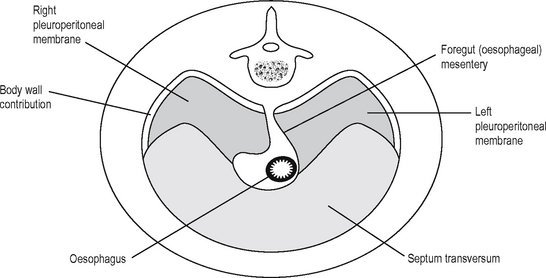

The diaphragm develops between the thoracic and abdominal cavity, and this is a complex process which is finished before the end of the eighth week (Fig. 16.4). As the embryo folds and carries the primitive heart and septum transversum caudally and ventrally, it carries part of the yolk sac dorsally to develop as the foregut. The lateral mesenchyme develops into the pericardioperitoneal canals, from which the pericardial cavity and the lungs develop, and is separated from the peritoneal cavity by the closure of the diaphragm. The motor nerve supply travels with the diaphragm as it descends, and so comes from a more cranial region than may be expected: C3–5. This explains the clinical observation that diaphragmatic inflammation/irritation, e.g. due to intraperitoneal blood, can demonstrate referred pain and can cause shoulder tip pain (which area is also supplied by C4).

The diaphragm develops from the fusion of four parts:

These diaphragmatic hernias must be dealt with surgically, after resuscitation of the patient (this is sometimes not possible in a neonate because of the severity of the lung hypoplasia) – up to 50% of babies born with congenital diaphragmatic hernias will die even today with all the modern management possibilities of oscillatory and jet ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (bypass).

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

OESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA

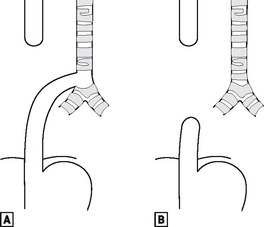

The foregut starts to divide into the oesophagus and the laryngotracheal tube during the fourth week. If it fails to do so correctly, there can be pure oesophageal atresia (in 8% of cases), or atresia associated with tracheo-oesophageal fistula – the commonest (in 80% of cases), being a fistula between the lower trachea and the distal oesophagus (Fig. 16.5).

INFANTILE HYPERTROPHIC PYLORIC STENOSIS

All of the gastrointestinal tract has two layers of muscle: circular and longitudinal. The circular muscle only of the pylorus can become hypertrophied in some babies. This is often called ‘congenital’ hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, but does not actually exist at birth. The baby usually presents after 10–50 days (most commonly 3–5 weeks), as the pyloric canal is narrowed by the hypertrophied muscle, and milk is prevented from leaving the stomach. The stomach becomes full and peristalses vigorously to try to empty. This peristalsis may be visible on the baby’s abdomen. The baby will then vomit forcefully, which is described as projectile.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree