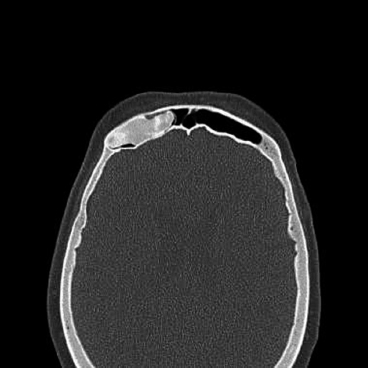

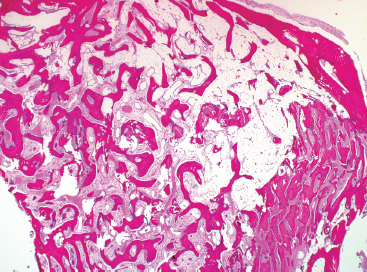

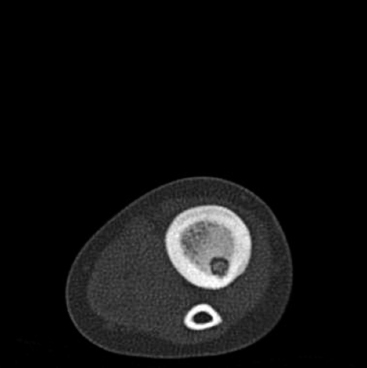

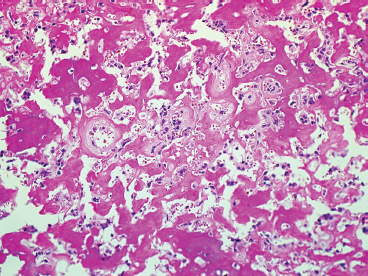

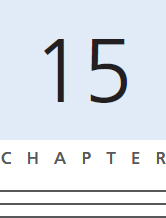

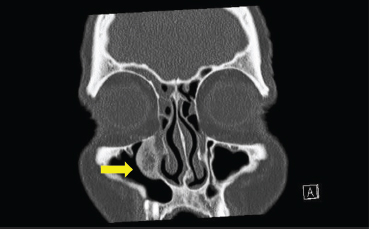

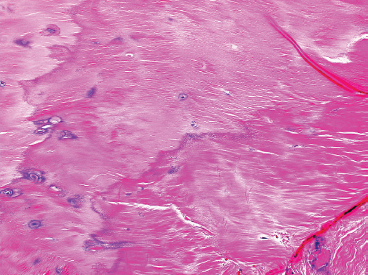

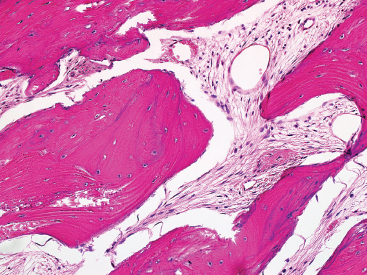

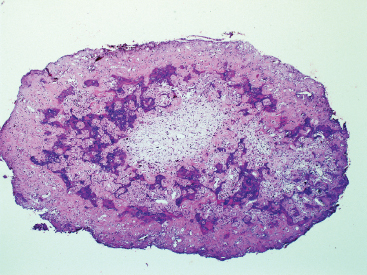

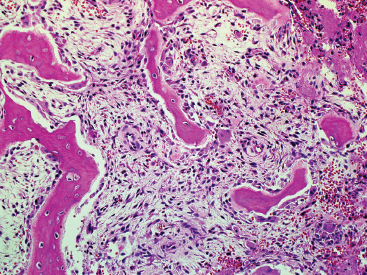

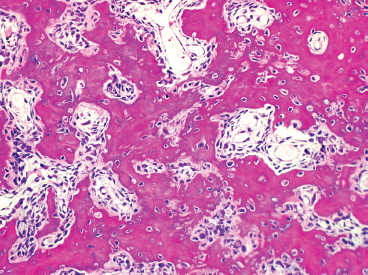

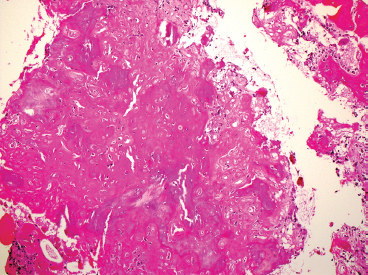

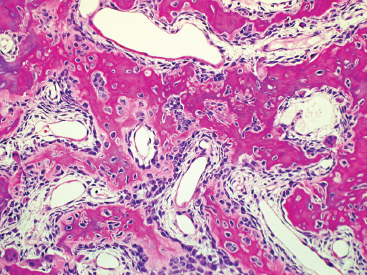

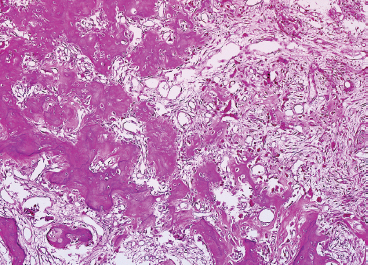

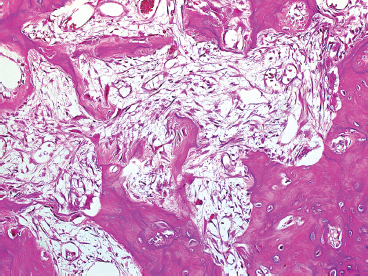

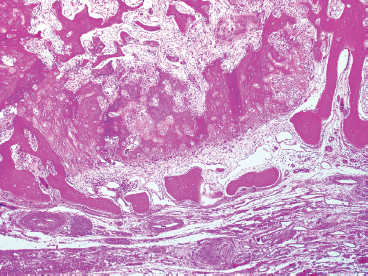

OSSEOUS LESIONS 15.5 Major Histologic Variants of Osteosarcoma Osteomas are benign proliferations of mature bone. They tend to grow along the surfaces of preexisting cortex and may occasionally be confused radiographically with other surface-based tumors, namely, parosteal osteosarcoma. Osteomas occur preferentially in the craniofacial skeleton, a site that is extremely rare for parosteal osteosarcoma. Occasional examples have been demonstrated on the surface of the long bones or in the vertebral column. In these unusual sites, the diagnosis of osteoma may be problematic. Osteomas are fairly common, with an estimated incidence of 1% to 3% of the general population. They represent the most common benign neoplasms of bone in the skull. They are frequently identified as incidental findings in individuals undergoing CT or MRI for an unrelated problem (Figures 15.1.1 and 15.1.2). They can occasionally be symptomatic, particularly when they are located in the sinuses or the orbit, where they can cause swelling and symptoms of compression. They can also cause headache, facial pain, and proptosis. They are usually solitary lesions, but can rarely be multiple. In the latter instance, osteomas may be a manifestation of Gardner syndrome (multiple intestinal polyps, fibromas, osteomas, dental lesions, and inclusion cysts). Gardner syndrome should be suspected when a very young individual presents with an osteoma. Osteomas are slow-growing, benign lesions. Unless they are symptomatic, or there is concern for a more aggressive process, they need not be excised. To date, there has not been a documented case of a malignant transformation of osteoma. Microscopically, osteomas emanate from the cortical surfaces of bone. They range in size from subcentimeter to about 2 cm in greatest dimension. They typically have a round to oval shape and cannot be removed without taking some of the underlying cortex. As mentioned before, osteomas are composed of mature bone. It may be dense cortical bone or lamellar in arrangement. The cortical type has a well-defined system of Haversian canals, with bone deposited circumferentially around small vessels (Figure 15.1.3). Alternatively, the bone may be arranged in thick lamellae with an intervening loose fibrous stroma (Figure 15.1.4). The latter arrangement is often seen in osteomas of the paranasal sinus region (Figure 15.1.5). In either configuration, the osteoblasts are usually very small and inconspicuous (Figure 15.1.6). Marrow elements can sometimes be identified in association with an osteoma. FIGURE 15.1.1 An osteoma in the frontal sinus. These are frequent incidental findings. FIGURE 15.1.2 An osteoma of the paranasal sinus region. These are often symptomatic, producing signs related to obstruction. FIGURE 15.1.3 Osteomas are often composed of dense and compact cortical-type bone with a mature Haversian canal system. FIGURE 15.1.4 Some osteomas have a more trabecular arrangement. FIGURE 15.1.5 An osteoma of the paranasal region with a small entrapped fragment of respiratory-type mucosa. FIGURE 15.1.6 High-power view of mature trabecular bone of osteoma. This pattern is virtually indistinguishable from normal bone. Osteoid osteoma (OO) is a benign bone neoplasm with a uniquely characteristic clinical and radiographic presentation. OO has a peak incidence in young individuals, usually children and adolescents. Adults are occasionally affected. OO has been reported to occur in just about any location, but it has a predilection for the long bones, the most common site being the femur. It tends to be a cortical bone-based lesion, sometimes very near the periosteal surface. Patients complain of a distinctive pattern of pain. The pain may wax and wane, but tends to become worse in the evening. The pain of OO has been attributed to local production of prostaglandins. One very characteristic feature of OO-associated pain is it is frequently relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSIADs). If OO is located near a joint, there may be swelling and a joint effusion that can result in inflammatory arthritis and secondary joint destruction. OO of the spine can present as scoliosis resulting from spasm of the adjacent spinal muscles. In addition to the clinical features, imaging studies are very helpful in confirming a diagnosis of OO. On plain films, the nature of the lesion may by be obscured by the presence of dense reactive bone, which surrounds the nidus of the lesion. The nidus, which is the pathognomonic feature of OO, may be difficult to demonstrate without cross-sectional imaging. Thus CT or MRI may be required to demonstrate the small (1 to 2 cm) nidus of dense bone within an area of radiolucency (Figure 15.2.1). In addition, CT scans should be performed at very small intervals or “cuts” in order to detect the nidus. Once the diagnosis of OO is confirmed, there are many options for treatment. Nonsurgical options include treatment with NSAIDs or aspirin. If the patient cannot tolerate a medical regimen, other options for treatment include surgical extirpation of the lesion or radiofrequency ablation. Because of an increase in the use of ablation-type procedures, OOs are less frequently seen as histologic specimens than previously. Recovery of an intact nidus is relatively uncommon (Figure 15.2.2). Instead, specimens are usually submitted as multiple fragments of bone, including reactive bone as well as fragments of the lesion (nidus) (Figure 15.2.3). Because the main differential diagnosis of OO is Brodie’s abscess (a type of focal, smoldering osteomyelitis), the presence of abundant reactive type bone may lead to diagnostic confusion. In addition, there may be considerable fragmentation of the bone (bone dust) or thermal artifact that makes recognition of OO almost impossible. The key to making the diagnosis is recognizing the histologically different-appearing bone of the nidus. That being said, the nidus has a variable appearance based on the age of the lesion. Most commonly, the nidus is more dense and sclerotic than the surrounding reactive bone. It is usually arranged in a more compact arrangement of woven bone on a background of fibrovascular stroma (Figures 15.2.4 and 15.2.5). In less mature lesions, there may be a rich, vascularized network of small vessels. Older lesions may lack a significant vascular component, having become obliterated as the lesion begins to involute (Figure 15.2.6). Ancillary techniques are of relatively little use in the diagnosis of OO. To date, a few cytogenetic studies of OO have been performed. They have shown a rare structural alteration involving 22q13. Cytologic descriptions of OO are exceeding rare as this is a lesion not particularly amenable to aspiration diagnosis for a number of technical reasons. Nevertheless, a radiologist or other interventionist may request an “immediate assessment” of a presumed OO preceding an image-guided ablation. In this instance, a specific diagnosis of OO is unrealistic. Instead, one may be able to exclude the presence of malignancy or acute inflammation, information that may be of value. FIGURE 15.2.1 Cross sectional imaging of osteoid osteoma (OO) demonstrates a nidus within a lucent cavity centered on the cortex. FIGURE 15.2.2 A surgically extirpated intact nidus. These are vanishingly rare as most lesions are curettaged or subjected to radiofrequency ablation. FIGURE 15.2.3 Fragments of reactive bone are often submitted in addition to the OO nidus. Reactive bone is a nonspecific finding and needs to be distinguished from the more compact bone of OO. FIGURE 15.2.4 An OO nidus with vey compact woven bone. The lesion is highly vascular, and there is brisk osteoblastic activity. FIGURE 15.2.5 In this example of an interior of a nidus, the bone is slightly more mature. There are still numerous small vessels throughout the lesion. FIGURE 15.2.6 Example of an old “burned-out” nidus of OO. This lesion contains very few vessels and limited osteoblastic activity. Note the presence of reactive bone in the upper corner. Osteoblastoma is a relatively rare neoplasm of bone with a strong predilection for the axial skeleton. It occurs predominately in the spine, particularly in the posterior elements, and also in the sacrum. It occasionally occurs in the long bones. In the femur and tibia, osteoblastoma may be difficult to separate from OO. In some cases, this difference is somewhat arbitrary, often based on the absolute size of the lesion (>2 cm favoring an osteoblastoma). Osteoblastoma affects a wide age range, but has a peak incidence in younger individuals (10–30 years old). There is a 2 to 1 male predominance of male-to-female patients. Signs and symptoms of osteoblastoma are similar to those of OO. These lesions tend to be painful and can produce local swelling. Of note, osteoblastoma-associated pain does not respond to anti-inflammatory medication in the same manner as OO. In the spinous processes, patients can present with scoliosis and/or nerve root compression. These clinical features, in addition to the imaging findings, often lead to a clinical impression of an aggressive or malignant process. Osteoblastomas generally have a very expansile appearance on imaging studies. In the long bones, there is usually an identifiable intact rim of cortex. In the spine, they may have a very destructive appearance and are often lytic with intralesional calcifications (Figures 15.3.1 and 15.3.2). They may also show focal cortical destruction. Despite their sometimes aggressive appearance, osteoblastomas are benign lesions and can be treated with a surgical excision. Curettage of an osteoblastoma may be insufficient to remove the entire lesion, with recurrence rates of up to 20% associated with this form of treatment. There are rare cases of the so-called “malignant transformation” of an osteoblastoma. This is an extremely infrequent occurrence and represents a controversial entity. The histology of osteoblastoma resembles that of OO in that it is composed of woven bone, arranged in irregular trabeculae. There is less likely to be a well-defined “nidus” identifiable in osteoblastoma, but the features of a benign osteoid-forming lesion within a shell of reactive bone are somewhat similar. Spicules of bone within the lesion are haphazardly or irregularly arranged. They are lined by a thin layer of very prominent plump osteoblasts. Occasionally these osteoblasts can be very large, have an “epithelioid” appearance, and can have very hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 15.3.3). The background stroma tends to be loose and hypocellular. Spindled cells are present, and mitoses may be identified. One of the most useful histologic features of osteoblastoma for diagnosis is the presence of numerous vessels within the lesion. This feature tends to be more central, giving the overall tumor a zonation pattern (Figure 15.3.4). Osteoblastoma is a richly vascular lesion with numerous vessels as well as occasional extravasated red blood cells. The vessels are dispersed throughout the lesion and appear as both large and small blood-filled spaces (Figure 15.3.5). These are usually not lined by a true endothelium. Additional elements often identified in osteoblastoma include rare osteoclast-like giant cells and occasional small foci of immature cartilage. As alluded to previously, osteoblastoma is often thought to be an aggressive lesion based on clinical and/or radiographic characteristics. In this instance, it is easy to misinterpret the irregular osteoid as a component of an osteosarcoma. One way to avoid this pitfall in diagnosis is to examine the (host) bone bordering the lesion (Figure 15.3.6). Osteoblastomas should not show a permeation pattern, histologically identifiable as invasion of the host trabecular or cortical bone. Instead, the host bone should show either sclerosis or reactive features, manifest as the presence of new bone laid down in an orderly fashion. Because of the presence of extensive bone within the lesion, osteoblastomas tend to aspirate very poorly. Needle biopsies tend to give very hemorrhagic specimens with rare spindled cells. These findings are relatively nonspecific. Cutting needle biopsy may yield a larger, more cellular specimen. Again, because of the presence of reactive bone, spindled stroma, and occasional nuclear atypia, this type of specimen may be very easy to “overdiagnose” as a malignant process. FIGURE 15.3.1 Axial CT view of an osteoblastoma of the spine. The lesion is lytic and has a destructive appearance. FIGURE 15.3.2 Coronal CT view of an osteoblastoma of the spine. FIGURE 15.3.3 Osteoblastomas are bone-forming lesions. Woven bone is deposited in an irregular pattern by osteoblasts. FIGURE 15.3.4 Often a zonation pattern can be identified in association with osteoblastoma. In this example, there is a transition from immature vascular stroma (right) to more organized woven bone on the left. FIGURE 15.3.5 Osteoblastomas tend to be very vascular with numerous small vessels identifiable within the stroma. FIGURE 15.3.6 One key to the benign nature of osteoblastoma is its lack of penetration of the surrounding bone. Osteosarcoma represents one of the most common primary tumors of bone. For classification purposes, osteosarcoma can be divided into conventional types (which include different subtypes), major histologic variants, and clinicopathologic subtypes (parosteal and periosteal osteosarcomas) that have different prognostic implications. In this section, the conventional type of osteosarcoma is discussed and illustrated. Important histologic variants are discussed separately. Osteosarcoma accounts for about 20% of all primary malignant bone tumors. Although no age group is exempt from this disease, there is a peak incidence in children, adolescents, and young adults. Over half of all cases of osteosarcoma occur before age 25. In older individuals, osteosarcoma is associated with radiation, often therapeutic, and Paget disease of the bone. Osteosarcoma can arise in any bone in the body, but there is a striking propensity for this tumor to occur in the metaphyseal regions of the long bones. The distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus represent the most common sites of involvement (Figure 15.4.1). Patients present with pain, and sometimes there is a noticeable mass or swelling in the affected region. In up to 10% of cases, the presenting sign is a pathologic fracture through the tumorous bone. A significant number of patients already have metastatic pulmonary disease at the time of presentation. On imaging, osteosarcoma appears as a destructive process that may be either blastic or lytic in nature. Cortical destruction is often evident, with extension of the lesion into adjacent soft tissue (Figure 15.4.2). At the leading edge of the tumor, the periosteum is often raised off the surface of the bone, resulting in a Codman’s triangle. Cross-sectional imaging is useful for determining the proximal and distal extent of the neoplasm and for identifying discontinuous foci (skip metastases) of tumor. Prior to the development of effective chemotherapeutic agents, osteosarcoma was an invariably fatal tumor. In the contemporary era, patients are commonly offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a delayed surgical resection. Patients with extremity-based lesions are often ideal candidates for limb salvage procedures. Although survival is affected by a number of factors including patient age, stage at presentation, and location of the lesion, patients who can tolerate chemotherapy often have prolonged 5- and 10-year survivals. The cytogenetics of conventional osteosarcoma are usually very complex. In addition, newer molecular techniques have uncovered numerous genes that are involved in tumor induction, progression, and metastases. To date, the discovery of a “targetable” oncogenic defect remains elusive.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree