6

Orbit

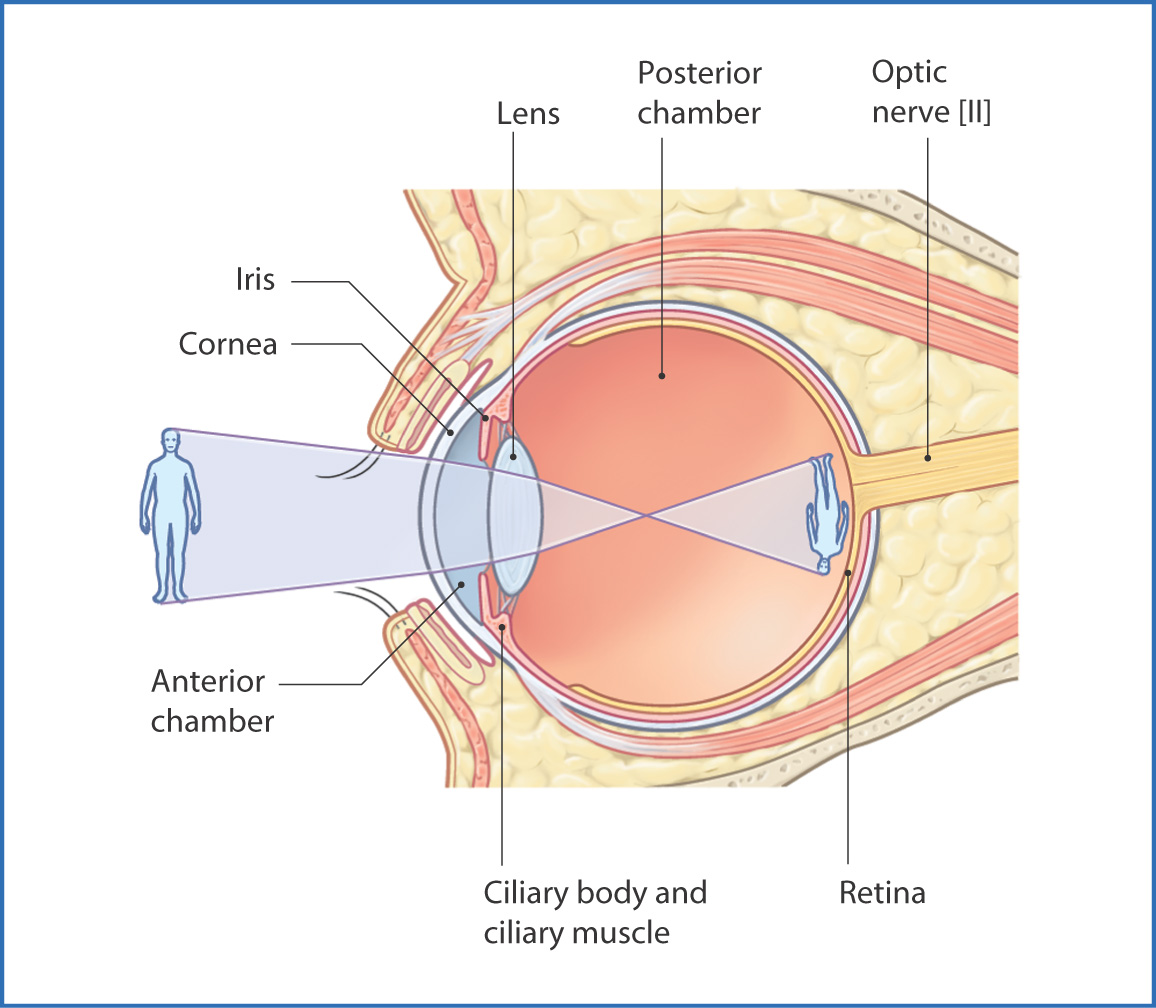

The eye is a complex organ that converts light entering it into a series of electrochemical signals that the brain interprets as a visual picture of the surrounding environment (Fig. 6.1). The eye has a tough outer covering, the sclera, that is visible externally as the “white” of the eye. In the central portion of the visible eye is the cornea, which is a transparent multilayered membrane through which light enters the eye and where preliminary focusing (primary refraction) occurs. Abnormalities in the cornea can therefore decrease visual capacity.

FIGURE 6.1 Section through the eye showing the pathway of light to the retina.

Deep to the cornea is the anterior chamber of the eye, which contains aqueous humor—a clear fluid through which light passes before entering the pupil. The pupil is a circular aperture surrounded by the iris, a contractile pigmented structure that regulates the amount of light entering the eye. From the pupil, light passes through the lens, where it is focused, and then through the vitreous humor (a clear, gel-like substance). It finally strikes the retina, from which photosensitive cells send nerve impulses to the brain.

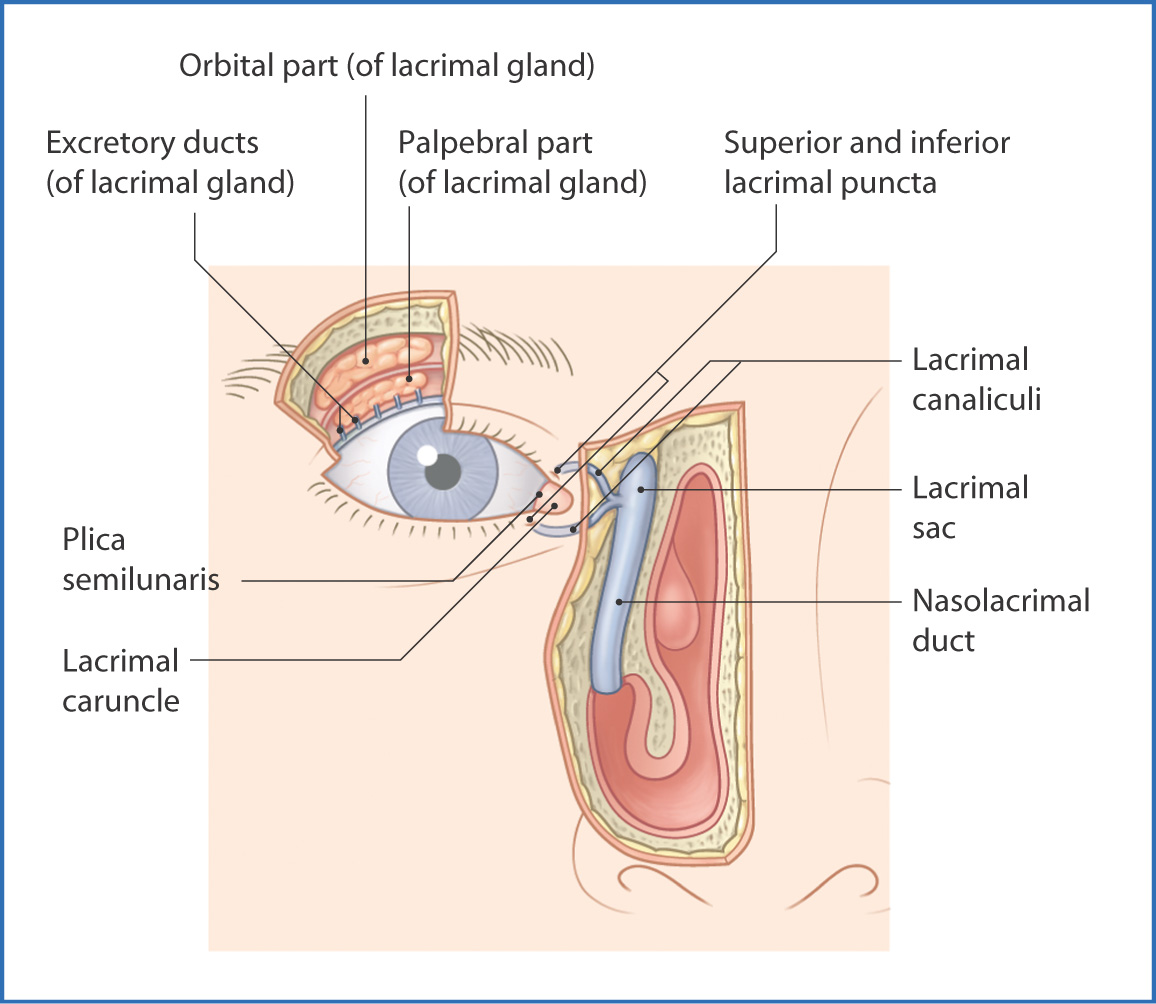

Lacrimal Apparatus

Tears, produced by the lacrimal apparatus, prevent drying of the cornea and conjunctiva, provide lubrication between the eye and eyelid, contain bactericidal enzymes, and improve the optical performance of the cornea. They supply oxygen to the avascular cornea. The lacrimal apparatus consists of the lacrimal gland and accessory lacrimal glands behind the upper eyelid in the superolateral angle of the orbit and the lacrimal duct system (Fig. 6.2). Tears pass through several ducts and move across the eye in a wave-like pattern created by the upper and lower eyelids during blinking. Blinking also aids in removing any foreign material and bacteria.

FIGURE 6.2 Lacrimal apparatus.

On the medial, superior, and inferior lid margins are two openings—the lacrimal puncta. These openings collect tears that have crossed the eye and transfer them to the lacrimal sac. Tears are then directed into the nasolacrimal duct, which empties into the nasal cavity. This connection between the eye and the nasal cavity explains why people often have a runny nose (clear rhinorrhea) when crying. Sensory innervation of the lacrimal gland is from the lacrimal nerves, which are branches of the ophthalmic nerve [V1]. The facial nerve [VII] provides preganglionic parasympathetic fibers, which enter the pterygopalatine ganglion. From there, nerve fibers enter the zygomatic branch of the maxillary nerve [V2] and the lacrimal nerve (of the ophthalmic nerve [V1]) to provide autonomic innervation.

Lymphatic drainage of the lacrimal gland is to the parotid nodes.

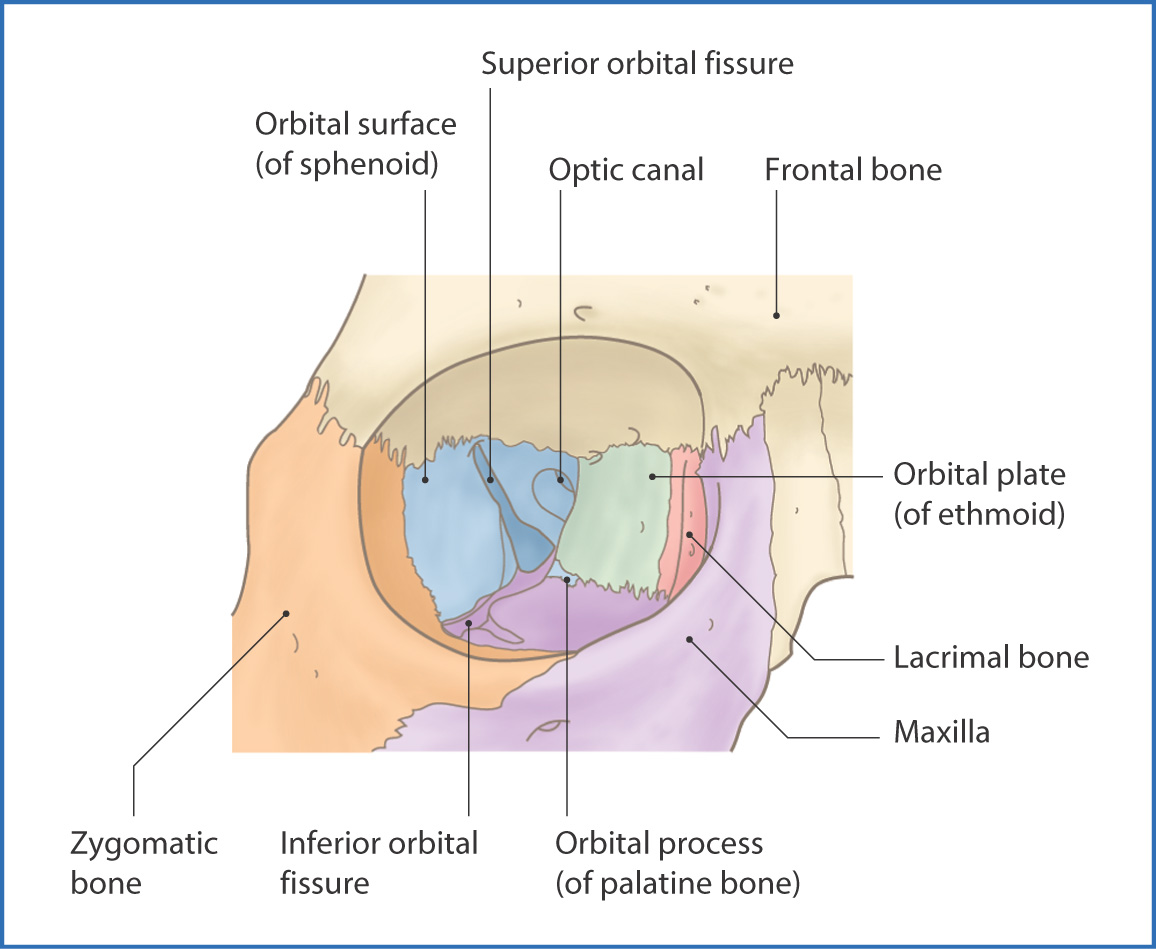

Bony Orbit

Each eye resides within an orbit that is pyramidal in shape; it has an open anterior margin (or base), a posterior apex, a roof, a floor, and medial and lateral walls (Fig. 6.3). The medial walls are parallel, whereas the lateral walls diverge from one another at 90°. Each orbital wall has several important adjacent relationships:

- roof—anterior cranial fossa, frontal sinus, and frontal lobes of the brain

- floor—maxillary sinus and infra-orbital nerves and muscles

- medial wall—ethmoidal cells, sphenoidal sinuses, and nasal cavity

- lateral wall—temporal fossa

- apex—middle cranial fossa, temporal lobes of the brain, infratemporal fossa, and pterygopalatine fossa

- floor—maxillary sinus and infra-orbital nerves and muscles

FIGURE 6.3 Walls of the orbit.

The apex of the orbit is at the optic canal, within the lesser wing of the sphenoid and just medial to the superior orbital fissure. The orbital margin, made up of parts of the frontal, zygomatic, maxillary, and lacrimal bones, forms a protective rim around the edges of the orbit. The bony elements of the orbital walls are the

- roof—orbital plate of the frontal bone and lesser wing of the sphenoid

- floor—orbital surface of the maxilla and contributions from the zygomatic and palatine bones

- lateral wall—frontal process of the zygomatic bone and greater wing of the sphenoid

- medial wall—orbital plate of the ethmoid, the lacrimal bone, the frontal process of the maxilla, and the body of the sphenoid

- floor—orbital surface of the maxilla and contributions from the zygomatic and palatine bones

Several foramina and fissures form passageways for the vital nerves and blood vessels that support the eye and for structures that pass through the orbit (see Fig. 6.3).

Muscles

Extrinsic muscles of the orbit (Table 6.1, Fig. 6.4) move the eyelids. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle is a sheet-like muscle that raises the superior eyelid and is innervated by the oculomotor nerve [III]. The orbicularis oculi

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree