One final important point concerning the histopathologic interpretation of inflammatory skin diseases is that the lesions are dynamic and change is an intrinsic quality. It must be remembered that a biopsy “captures” the histopathology of the lesion at one point in its evolution. Many inflammatory skin diseases may only be readily diagnosed microscopically at certain points within the spectrum of changes. If a lesion is biopsied early or late in its evolution, the microscopic findings may be nondiagnostic.

SPECIMEN PREPARATION

Careful gross processing of skin biopsies is critical for accurate microscopic interpretation. The shave, punch, and elliptical biopsy techniques are most frequently used to obtain skin specimens for microscopic examination.

The elliptical excision is preferred when the disease process involves the deep dermis or subcutis. Superficial fascia can only be obtained reliably with this technique. In our experience, the “bread-loaf” method (sequential serial sectioning) of cutting skin ellipses is best because it is simple, can be performed rapidly, and ensures adequate sampling of the tissue. The skin ellipse is cut perpendicular to the long axis of the specimen at approximately 3-mm intervals. If the cut surface is marked with ink and each tissue slice is embedded in a separate cassette, it is easy to decide which block to recut if additional sections are needed. Some dermatopathologists prefer to section skin ellipses longitudinally in nonneoplastic lesions. For the most part, the choice is a personal one.

The punch biopsy tool is best used to obtain a cylinder of skin that includes the epidermis, dermis, and a small amount of subcutis. Punch biopsies 4 mm in diameter or greater should be bisected before embedding. Smaller punch biopsy specimens are difficult to bisect and should be embedded intact.

The shave or tangential technique (blade parallel to the skin surface) is of limited value for the study of inflammatory skin diseases because only epidermis and superficial dermis are consistently sampled by this method. Shave biopsy specimens should be bisected or trisected if large enough so that a straight edge is available for microtome sectioning. Applying ink to the cut edge with an applicator stick enables the histotechnologist to identify the cut edge.

Ten percent buffered formalin is an excellent general-purpose fixative for skin specimens. Fixation in B5 solution results in the greater preservation of nuclear detail and is especially useful for evaluating lymphocytic infiltrates clinically suspicious for cutaneous lymphoma.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) is the most commonly used routine stain in dermatopathology, but most special stains used in general surgical pathology are also employed. Specific uses of histochemical stains and immunohistochemistry will be discussed along with the diseases in which their use is of value (1–4).

In dermatopathology, it is important to recreate a three-dimensional mental picture of the two-dimensional microscopic sections. In addition, many inflammatory skin diseases are particularly zonal in their microscopic architecture. Therefore, it is frequently helpful to make either step or serial sections from the paraffin block to maximize the yield of information obtainable from the microscopic sections.

Transverse sectioning of punch biopsies from the scalp is frequently used in the diagnosis of alopecia. A detailed discussion of this technique is beyond the scope of this chapter (5–7).

NORMAL HISTOLOGY

The skin comprises three structures: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutis. The superficial fascia marks the deep boundary between the skin and the underlying soft tissues. Regional anatomic variation of the skin is readily apparent if one compares a specimen from the scalp with one from the palm.

The epidermis is derived from ectoderm and composed of four layers or strata. The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis. The fully keratinized cells of this layer are flattened and devoid of nuclei. On acral surfaces (palms and soles), a thin stratum lucidum (clear zone) is present between the stratum corneum and the stratum granulosum. The stratum granulosum is named for the prominent deeply basophilic keratohyalin granules found in flattened keratinocytes. Deep to the stratum granulosum is the stratum spinosum, which is characterized by abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid nuclei, and intercellular bridges. The stratum basale (basal cell layer) is the undulating row of cuboidal to columnar cells with minimal cytoplasm and contains proliferating cells for epidermal renewal (8). The basal cells attach to the basement membrane of the epidermis. The stratum spinosum and the basal cell layer are collectively referred to as the stratum malpighii.

Although the majority of cells in the epidermis are keratinocytes, other cell types are present. Melanocytes are neural crest–derived dendritic clear cells situated in the basal zone. The primary function of melanocytes is the production of melanin. Langerhans cells are antigen-processing dendritic cells that are usually interspersed among the keratinocytes of the stratum spinosum but are virtually impossible to see in routine sections. Immunohistochemistry for S-100 protein is positive in both melanocytes and Langerhans cells, but Langerhans cells also express CD1a (9). Merkel cells are sparsely present neuroendocrine cells in the epidermis and function in mechanoreception. Merkel cells are not readily apparent in routine sections (9).

The basement membrane zone that separates the epidermis from the dermis appears to be a homogeneous eosinophilic band with light microscopy but displays a multilayered, complex arrangement at the ultrastructural level. The basement membrane zone is composed of four main layers: the basal cell hemidesmosome, the lamina lucida, the lamina densa, and the sublamina densa (8).

The most superficial level of the dermis is called the papillary dermis because it is located between the downward projections of the epidermis (rete ridges). The dermal papillae have a complex “hand-in-glove” relationship with the epidermal rete ridges. The deep border of the papillary dermis extends to the superficial vascular plexus and reticular dermis. Although it is a small part of the dermis quantitatively, the papillary dermis is important in many inflammatory skin diseases, and it functions as an anatomic buffer zone between the epidermis and reticular dermis.

In addition to its superficial location, the papillary dermis is characterized by a collagen pattern that is distinctively delicate and pale in H&E-stained sections. The adventitial dermis, the fine collagen fibers that invest adnexal structures, blood vessels, and nerves, is continuous with the papillary dermis.

The reticular dermis makes up the bulk of the dermis. Here, the collagen fibers are large, coarse, and brightly eosinophilic. Most of the adnexal structures are found within the reticular dermis. Progressively narrowing projections of the reticular dermis extend in a netlike manner into the subcutis to form the retinacular dermis.

The subcutis is the deepest layer of the skin. It is composed of collagenous septa and lobules of adipocytes. The fibrous septa connect the retinacular dermis with the superficial fascia to which the skin is anchored (10).

The cutaneous adnexa include hair follicles, sebaceous glands, eccrine glands, and apocrine glands (10). The hair follicle is a complex structure (5). The anagen, or growing, hair follicle can be divided into several parts. The deepest part, the hair bulb, is formed from both ectoderm (hair matrix) and mesoderm (dermal papilla). The isthmus extends from the superficial part of the hair bulb to the sebaceous duct. The infundibulum connects the isthmus and sebaceous duct to the epidermis. The intraepidermal portion of the hair follicle is called the acrotrichium. The sebaceous lobules empty into the follicle via the short sebaceous duct. An arrector pili muscle attaches to the isthmus below the entrance of the sebaceous duct at an area of the follicle termed the bulge.

The telogen, or resting, hair follicle lacks the well-defined components of the anagen, or growing, follicle. Instead, only a small ball of basaloid keratinocytes is located below the level of the sebaceous duct (5).

Sebaceous glands have a widespread distribution and are typically associated with hair follicles (10). In the eyelids, they are not associated with hair follicles and are known as the meibomian glands and glands of Zeis. Sebaceous glands secrete a lipid material known as sebum.

The eccrine glands are present at essentially all sites and are composed of a deep dermal or subcutaneous coil, mid dermal coiled and straight ducts, and an intraepidermal acrosyringium (10). Cuboidal epithelial cells surrounded by myoepithelial cells line eccrine ducts. The eccrine glands’ primary function is thermal regulation.

Apocrine glands are much more limited in distribution than eccrine glands and are primarily present in the axillary and anogenital regions (10). Modified apocrine glands are present in the external ear canal as ceruminous glands and in the eyelid as a gland of Moll. The apocrine epithelium consists of eosinophilic, cuboidal to columnar cells with decapitation secretion. Myoepithelial cells surround the outer portion of the apocrine glands and ducts. Their dermal duct usually ends in the follicular infundibulum, only rarely opening into the surface epidermis. The function of apocrine glands in humans is unknown.

The dermis is rich in blood vessels and lymphatics. The skin vasculature is supplied by perforating arteries of subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. The capillaries, arterioles, and venules of the superficial vascular plexus are located at the junction of the papillary and reticular dermis. Vessels extend from this plexus into the adventitial dermis of the adnexa and also penetrate through the reticular dermis to connect with the deep vascular plexus composed of larger vessels at the level of the deep reticular dermis. From the deep vascular plexus, vessels extend into the fibrous septa of the subcutis (10).

Aside from specialized end organs such as the Meissner and pacinian corpuscles, the nerves of the dermis are inconspicuous (10). They progressively decrease in caliber as they become more superficial. In the deep dermis, they usually course adjacent to blood vessels.

INFLAMMATORY SKIN DISEASE

PATTERNS OF EPIDERMAL INFLAMMATION

Spongiotic Dermatitis

Spongiotic dermatitis encompasses a wide range of disease processes that is perhaps the most extensive in dermatopathology (11–14). Microscopic spongiotic dermatitis correlates with clinical eczematous dermatitis, a spectrum of diseases with equally diverse causes and clinical presentations. The common denominator of spongiotic dermatitis is the presence of intraepidermal edema, which is referred to as spongiosis because the clear spaces separating the keratinocytes impart a spongy appearance to the epidermis. Spongiotic dermatitis is subclassified into acute, subacute, and chronic subtypes, depending on the presence or absence of several additional features that are discussed later. These terms relate loosely to the chronologic evolution of the spongiotic lesion. In summary, spongiotic dermatitis comprises a spectrum of histopathologic changes, with the acute and chronic subtypes at the polar ends and the subacute subtype occupying the broad middle.

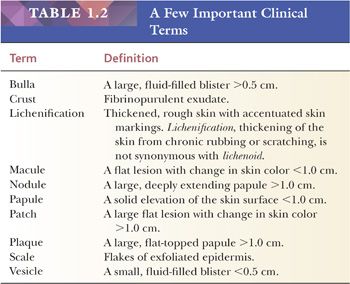

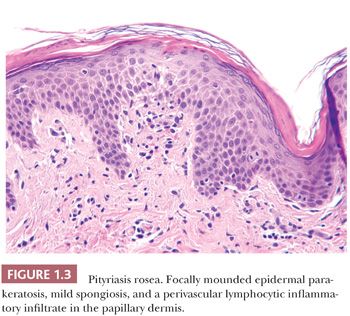

Epidermal spongiosis, with or without lymphocyte exocytosis, is the main microscopic finding in acute spongiotic dermatitis. Perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates, which are usually localized to the superficial dermis, accompany the epidermal spongiosis. In subacute spongiotic dermatitis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and less commonly papillomatosis are present to varying degrees (Fig. 1.1). The spongiosis ranges from minimal to marked. Eosinophils may be admixed in the inflammatory cell infiltrate, and this finding may be helpful in suggesting an allergic etiology. In contrast to acute and subacute spongiotic dermatitis, chronic spongiotic dermatitis may show little, if any, spongiosis. Acanthosis, parakeratosis, and papillomatosis overshadow spongiosis at this stage in the evolution of the disease (15). Fibroplasia of the papillary and upper reticular dermis may be present, and the inflammatory cell infiltrates, primarily lymphocytes, range from extensive to scant.

An important differential diagnosis in this category of diseases is between spongiotic dermatitis and early, patch-stage lesions of the mycosis fungoides type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Dermatologists often biopsy long-standing eczematous patches and plaques that do not resolve with topical corticosteroid therapy, because the patch stage of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can clinically mimic eczematous dermatitis. Atypical intraepidermal lymphocytes with convoluted (“cerebriform”) nuclei and perinuclear halos, especially when these are grouped into clusters known as “Pautrier microabscesses,” suggest the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Linear aggregates of lymphocytes aligned at the basal epidermis are also a helpful diagnostic finding in patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Although these findings are useful in distinguishing patch-stage mycosis fungoides from spongiotic dermatitis and other inflammatory mimics, they may be absent or very focal in early mycosis fungoides, and close correlation with the clinical presentation is essential to establish a diagnosis.

The term epidermotropism is used to describe the presence of atypical lymphocytes within the epidermis in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Epidermotropism should not be confused with exocytosis, the term used to denote the presence of lymphocytes in the epidermis in spongiotic dermatitis and other inflammatory diseases. Exocytosis implies the absence of nuclear atypia, but determining whether intraepidermal lymphocytes are atypical can be difficult, especially since the lymphocytes of many spongiotic processes are “activated” and their nuclei are larger with more complex contours than those of small lymphocytes. Associated spongiosis is useful in differentiating between the two because spongiosis is almost always present to some extent in spongiotic dermatitis (exocytosis) but is usually more limited in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (epidermotropism). A cautious approach to the interpretation of the cytologic features of intraepidermal lymphocytes is essential to avoid confusing spongiotic dermatitis with early, patch-stage lesions of mycosis fungoides. In cases of histopathologic uncertainty, conservative interpretation and clinical correlation are imperative. Additional specimens taken over a period of time may be required before arriving at an accurate diagnosis. Evaluation by molecular diagnostic studies for the presence of a clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement is an important ancillary study, but correlation with the clinical features is essential.

Acute and Subacute Spongiotic Dermatitis

ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS

CLINICAL FEATURES. Allergic contact dermatitis develops when the skin comes into contact with a substance, such as nickel or the poison ivy plant, to which the patient has been previously sensitized. The dermatitis appears at the site of contact with the offending agent.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Allergic contact dermatitis begins as acute spongiotic dermatitis, and it may evolve into subacute or chronic spongiotic dermatitis before resolving (11). Typically, the spongiosis is extensive. Spongiotic intraepidermal vesicles may form. Lymphocyte exocytosis is generally present. Papillary dermal edema may also be present. The dermis typically displays a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with varying numbers of admixed eosinophils. The presence of numerous eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate helps to differentiate allergic contact dermatitis from other types of spongiotic dermatitis.

IRRITANT CONTACT DERMATITIS

CLINICAL FEATURES. Contact with an irritant substance may lead to irritant contact dermatitis (15). Irritants differ from allergens in that no prior sensitization is required for the dermatitis to develop. Soaps and detergents are common irritants.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The histopathology is similar to that of allergic contact dermatitis except that eosinophils are either absent or rare (15). Strong irritants may lead to superficial epidermal necrosis associated with intraepidermal neutrophils and a fibrinopurulent exudate.

Endogenous Eczema Group

ATOPIC DERMATITIS, NUMMULAR ECZEMA, SEBORRHEIC DERMATITIS, DYSHIDROTIC ECZEMA (POMPHOLYX)

CLINICAL FEATURES. This group of eczematous disorders encompasses many varied clinical presentations ranging from discrete, round to oval, 1- to 3-cm patches (nummular eczema) to erythematous, scaly patches and thin plaques (seborrheic dermatitis) to generalized exfoliative dermatitis (severe atopic dermatitis). These diseases are “endogenous” in the sense that they are not secondary to any known exogenous agents. However, persons with atopic dermatitis are generally more susceptible to irritant contact dermatitis. Therefore, the histologic picture can be a combination of the two processes.

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Generally, these clinically diverse entities are inseparable microscopically, and they encompass the full range from acute to subacute to chronic spongiotic dermatitis. Large, intraepidermal spongiotic vesicles may form on the palms or soles in dyshidrotic eczema. A shift from subacute spongiotic dermatitis to a more acute pattern may indicate the presence of an irritant dermatitis superimposed on a chronic atopic dermatitis.

Chronic Spongiotic Dermatitis. Chronic spongiotic dermatitis is characterized by irregular epidermal acanthosis. Although the term may be used as synonym with chronic spongiotic dermatitis, prurigoform acanthosis implies a position at the extreme end of the spectrum of acanthosis in which epidermal hyperplasia is extensive. This pattern has been separated from acute and subacute spongiotic dermatitis solely for the purpose of pattern recognition. Prurigoform acanthosis and chronic spongiotic dermatitis are the result of sustained irritation of the skin, frequently by rubbing or scratching.

The differential diagnosis of chronic spongiotic dermatitis is similar to that of subacute spongiotic dermatitis and includes the mycosis fungoides type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The same histologic criteria used for differentiating acute and subacute spongiotic dermatitis from cutaneous mycosis fungoides apply to chronic spongiotic dermatitis. Spongiosis is not as prominent, so eliminating mycosis fungoides from the differential diagnosis can be more difficult than in the more acute spongiotic processes. Keratinocytic neoplasms that can be confused with chronic spongiotic dermatitis include hypertrophic actinic keratosis and early squamous cell carcinoma. The presence of keratinocyte atypia is useful in differentiating the latter from chronic spongiotic dermatitis.

LICHEN SIMPLEX CHRONICUS (PRURIGO NODULARIS)

CLINICAL FEATURES. Lichen simplex chronicus lesions are the result of chronic rubbing or scratching (16). The plaques of lichen simplex chronicus are scaly, thickened, moderately erythematous, and better demarcated than their more acute counterparts. The term prurigo nodularis implies a raised, pruritic nodule. Secondary changes such as excoriation, lichenification, and crusting are common.

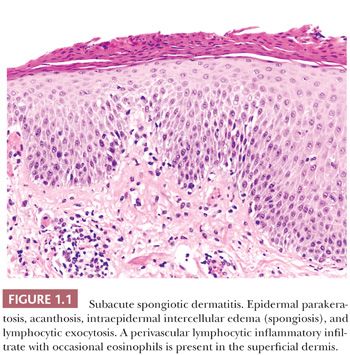

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The key epidermal finding in this group is markedly irregular psoriasiform acanthosis (Fig. 1.2). Hyperkeratosis with admixed orthokeratosis and parakeratosis is common and may be extensive. A prominent epidermal granular layer is usually present (16,17). Spongiosis may be absent or minimal. When spongiosis is present, it is typically localized to discrete foci. Fibrosis of the underlying dermis is variable, ranging from linear fibrosis of the papillary dermis to superficial dermal scars. Hyperplasia of small dermal nerve trunks has been observed within the dermal scars (18).

PITYRIASIS ROSEA

CLINICAL FEATURES. Patients presenting with numerous oval patches on the trunk with collarettes of scale in conjunction with a single, larger “herald patch” typify pityriasis rosea (19,20). A link to a viral etiology has been sought and debated in the literature. The clinical differential diagnosis frequently includes secondary syphilis.

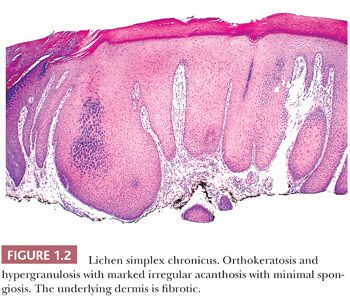

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The histopathology of pityriasis rosea is essentially that of subacute spongiotic dermatitis (19,20). In most cases, differentiating pityriasis rosea from other forms of subacute spongiotic dermatitis is difficult if not impossible without clinical information. Foci of extravasated erythrocytes in the papillary dermis and the presence of discrete mounds of parakeratosis rather than of diffuse parakeratosis are of value in making the diagnosis (Fig. 1.3). The absence of plasma cells from the dermal infiltrate in conjunction with the described epidermal changes aids in separating pityriasis rosea from secondary syphilis, although plasma cells are not always present in the dermal infiltrate of secondary syphilis. Treponemal immunohistochemistry is useful to exclude syphilis. In addition, correlation with treponemal serologic studies is advised if there is clinical suspicion for secondary syphilis.

DERMATOPHYTOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES. Superficial fungi, or dermatophytes, may cause disease of the skin of the scalp (tinea capitis), face (tinea faciale), trunk (tinea corporis), palm (tinea manuum), groin (tinea cruris), or sole (tinea pedis) (21). Scaly, red annular plaques characterize the classic ringworm of tinea corporis, but other presentations frequently pose a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. Fungal infection of the nail (onychomycosis) can also be evaluated by the histologic examination of nail clippings.

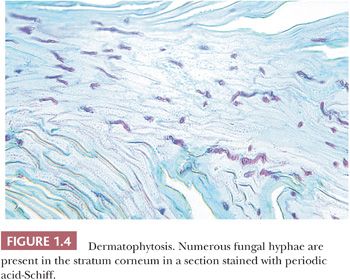

HISTOPATHOLOGY. A useful diagnostic clue to the presence of a dermatophyte infection is the finding of neutrophils in the epidermis or epidermal stratum corneum in addition to the other changes of spongiotic dermatitis. Frank pustulation may occur. The hyphae are usually limited to the stratum corneum and are frequently seen either within or adjacent to a follicular orifice. Hyphae can be seen in sections stained with H&E, but they are much easier to identify in sections stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), in which they are diastase resistant (Fig. 1.4) (21). The yeast forms, and the short, thick hyphae of Pityrosporum species, as well as the pseudohyphae and budding yeasts of Candida species, can be confused morphologically with the true hyphae of dermatophytes. In true dermatophyte fungal infections, slender, septate, or nonseptate hyphae predominate.

ADJUNCTS TO MICROSCOPIC DIAGNOSIS. Fungal cultures from stratum corneum scrapings provide definitive characterization of fungal organisms and are recommended to guide therapy.

LICHEN STRIATUS

CLINICAL FEATURES. The linear, small, flesh-colored papules of lichen striatus are most commonly found on the extremities of children (22,23).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Despite the inclusion of lichen in the name, the major histologic features are spongiosis and vacuolar epidermal interface alteration (22,23). The spongiotic changes are usually subacute (i.e., accompanied by acanthosis and parakeratosis). The dermis displays a superficial and deep lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate distributed at the dermal-epidermal interface and around vascular channels and eccrine coils. The presence of a deep component of the inflammatory infiltrate is helpful in the distinction from other lichenoid lesions.

Stasis Dermatitis

Clinical Features. Chronic venous stasis can lead to the development of the scaly erythematous plaques of stasis dermatitis on the lower extremities (24). Secondary infection and ulcer formation are common.

Histopathology. In stasis dermatitis, subacute spongiotic changes are present over a bandlike zone of dilated capillaries in the papillary dermis (24). Reticular dermal fibroplasia and hemosiderin deposits are usually present in older lesions. Lobular proliferations of small capillaries, in conjunction with hemosiderin deposition, may resemble patch-stage or plaque-stage Kaposi sarcoma (24).

Psoriasiform Dermatitis

Psoriasiform dermatitis is characterized by regular epidermal acanthosis, parakeratosis, and a reduced or absent granular layer. The prototype disease of this group is psoriasis vulgaris.

Psoriasis Vulgaris

CLINICAL FEATURES. Psoriasis is a common skin disease characterized by raised, sharply defined, erythematous plaques with a silvery scale. The typical locations of the plaques include the scalp, elbows, extensor knees, umbilicus, and sacral areas (25). The degree of involvement ranges from single plaques to generalized exfoliative dermatitis. The pathogenesis of psoriasis is not fully understood.

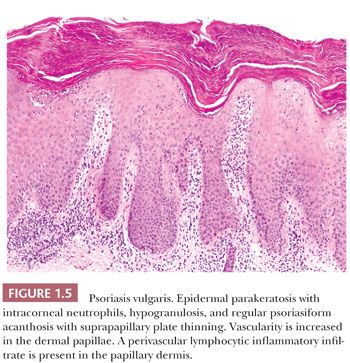

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Diffuse epidermal parakeratosis, reduced or absent granular layer, regular psoriasiform epidermal acanthosis with suprapapillary plate thinning, increased vascularity of the papillary dermal papillae, and a sparse perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate are diagnostic features in well-developed lesions of psoriasis (26–29). The elongated and narrowed rete ridges have a “comblike” appearance (Fig. 1.5). Additional diagnostically helpful findings include collections of neutrophils either in the parakeratotic stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or at the interface of the stratum malpighii and stratum corneum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj) (26). The latter two changes may be absent in late-stage or partially treated lesions. Lesions of lichen simplex chronicus are in the differential diagnosis of psoriasis and are distinguished from psoriasis by the presence of predominantly epidermal orthokeratosis and hypergranulosis and the absence of increased papillary dermal vascularity in lesions of lichen simplex chronicus.

Pustular Psoriasis

CLINICAL FEATURES. This variant of psoriasis is characterized by multiple sterile pustules on an erythematous base (30). It may involve extensive areas, or it can be limited to the palms and soles (pustulosis palmaris et plantaris).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Subcorneal aggregates of neutrophils (pustules) are generally larger and more discrete than the intraepidermal aggregates of neutrophils seen in psoriasis vulgaris (30,31). A lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with a few neutrophils is present in the papillary dermis. The characteristic epidermal features of psoriasis may be absent, slightly developed, or well-developed in pustular psoriasis lesions (30). Because lesions of pustular psoriasis may lack diagnostic features of psoriasis, the findings may not be specific and the differential diagnosis includes bacterial and fungal infections, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, and immunobullous diseases such as pemphigus foliaceus and the subcorneal variant of immunoglobulin A (IgA) pemphigus. In addition, pustular cutaneous lesions of reactive arthritis (Reiter syndrome) show essentially identical histopathologic features as pustular psoriasis requiring clinical correlation for distinction (31).

Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

CLINICAL FEATURES. Pityriasis rubra pilaris frequently presents with erythroderma closely resembling psoriasis (32,33). In contrast to psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris is characterized by areas of normal skin (islands of sparring) encompassed by erythematous to salmon-colored scaly plaques (island-sparing) and perifollicular horny spines (32).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Despite the characteristic clinical presentation, the microscopic findings in pityriasis rubra pilaris are frequently nonspecific but in some cases can be indistinguishable from those of psoriasis (32,33). Pityriasis rubra pilaris is characterized by horizontally and vertically alternating tiers of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum, focal hypergranulosis, and mild to moderate psoriasiform acanthosis (32). Epidermal hypergranulosis, acrotrichial parakeratosis (follicular plugging), and an absence of papillary dermal vascular changes can help to differentiate pityriasis rubra pilaris from psoriasis, but clinical correlation is often required.

Lichenoid Interface Dermatitis

Lichenoid interface dermatitis is one of two major inflammatory patterns that primarily involve the epidermal basement membrane zone, hence the use of the term interface. The other pattern is vacuolar interface dermatitis (discussed later in this chapter in the section “Vacuolar Interface Dermatitis”). These two patterns can be difficult to separate at times, and both changes may be present in the same lesion.

Lichenoid interface dermatitis is defined by the following two patterns at the basement membrane zone: the destruction of the basal keratinocytes and a superficial, bandlike lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate of varying density closely approximating the epidermis. The cytoplasm of the altered basal keratinocytes becomes brightly eosinophilic. The nucleus, which is at first pyknotic, is later extruded so that eventually round to oval eosinophilic bodies are found in the lower epidermis and upper papillary dermis (34). These structures have been termed colloid bodies or cytoid bodies. The normal ordered arrangement of basal keratinocytes and the sharply defined basement membrane zone are both eventually destroyed. With the regeneration of the keratinocytes, the basement membrane zone takes on a disorderly, irregular appearance. The regular, undulating rete ridge pattern is lost, and the normally cuboidal basal keratinocytes become variable in shape.

A lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate is present in the superficial dermis adjacent to the altered keratinocytes. The lymphocytic infiltrate ranges from sparse to dense but is generally moderate to dense. Melanophages may be present in the underlying papillary dermis (pigment incontinence).

Lichenoid epidermal interface alteration frequently overlaps with the vacuolar epidermal interface alteration. Careful examination of the basement membrane zone and associated inflammatory infiltrate is essential in distinguishing between the two patterns. Dyskeratosis predominates in the lichenoid pattern, whereas vacuolization of the basal keratinocytes is the hallmark of the vacuolar pattern. A combination of both lichenoid and vacuolar interface alteration may be present in certain dermatoses, such as lupus erythematosus.

Lichen Planus

CLINICAL FEATURES. “Purple, pruritic, polygonal papules” accurately sums up the clinical presentation of lichen planus (34–36). The papules tend to occur on the flexor surfaces of the extremities rather than on the dorsal surfaces. In addition, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp may be affected. When the terminal hairs of the scalp are the primary site of involvement and there is resultant alopecia, the term lichen planopilaris is used (37). Lichen planus is also associated with hepatitis C infection (38). Rare cases of squamous cell carcinoma arising in lesions of oral lichen planus have been reported (39).

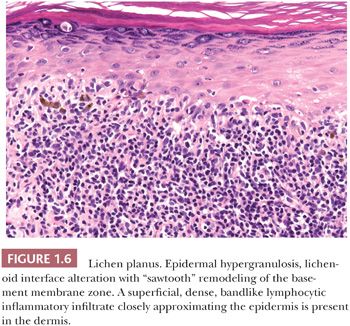

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Lichen planus is the prototype of lichenoid interface dermatitis (Fig. 1.6). In addition to lichenoid interface change, several other features are seen in lichen planus. Acanthosis is characteristically present, and in some cases, it may be extreme and mimic squamous cell carcinoma (hypertrophic lichen planus). Alternatively, there is a variant of lichen planus that is called atrophic lichen planus, in which the epidermis is atrophic (34). Epidermal hyperkeratosis is a regular feature of lichen planus. The hyperkeratosis is typically orthokeratotic, and the presence of parakeratosis can suggest another lichenoid disease. The epidermal granular layer often shows focal “wedge-shaped” hypergranulosis. The irregularity of the lichenoid interface change results in the “sawtooth” appearance of the basement membrane zone. Colloid bodies range from rare to abundant. Artifactual cleft formation (Max-Joseph space) between the epidermis and papillary dermis is common, and frank hemorrhagic subepidermal bullae may occasionally be seen. The inflammatory infiltrate in lichen planus is superficial, typically moderate to dense, predominantly lymphocytic, and displays a bandlike distribution closely approximating the epidermis. Melanophages may be abundant, especially in lesions involving darkly pigmented skin (34).

In lichen planopilaris, similar changes are seen; however, lichen planopilaris contrasts with ordinary lichen planus in that most of the alteration occurs at the level of the follicular infundibulum (37). Lichen planopilaris frequently leads to follicular destruction that is characterized by perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates, remnants of the follicular epithelium, and “naked” hair fibers partly engulfed by mononucleated or multinucleated phagocytes in late-stage lesions.

Lichen Nitidus

CLINICAL FEATURES. In lichen nitidus, a childhood eruption, groups of pinpoint, round, asymptomatic, flesh-colored papules are located primarily on the trunk, genitalia, abdomen, and forearms (40).

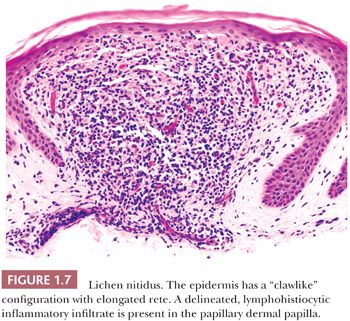

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Only minimal lichenoid interface change is typically present in lichen nitidus. The epidermis has a “clawlike” configuration in which curvilinear fingerlike extensions of the epidermal rete surround a papillary dermal inflammatory infiltrate in a discrete and discontinuous pattern (Fig. 1.7) (40). The dermal infiltrate is predominantly lymphocytes and histiocytes and may be loosely granulomatous. Parakeratosis may be present. Occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes may be present at the dermal-epidermal junction. As in other lichenoid diseases, the inflammatory infiltrate is superficial and closely approximates the epidermis.

Lichenoid Drug Eruption

CLINICAL FEATURES. A lichen planus–like eruption may develop after exposure to various drugs and chemicals, such as gold salts, thiazide diuretics, antimalarial drugs, penicillamine, and beta-blockers (41,42).

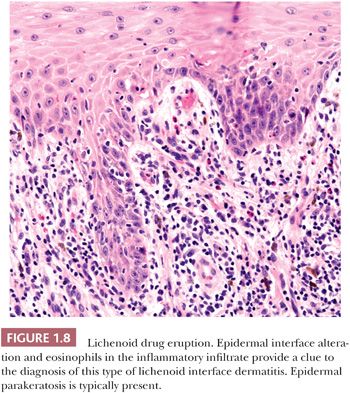

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Lichenoid drug eruptions may closely resemble lichen planus (41,42). Differentiating features of lichenoid drug eruption from lichen planus include the presence of epidermal parakeratosis and a more mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate including eosinophils and plasma cells (Fig. 1.8) (42).

Vacuolar Interface Dermatitis

Vacuolar interface dermatitis is the second of the basement membrane zone “interface” patterns. The term vacuolar refers to the finding of intracytoplasmic vacuoles within the cytoplasm of the basal keratinocytes. As in lichenoid interface dermatitis, the end result is an alteration of the normal orderly arrangement of basal keratinocytes and the basement membrane zone. Vacuolar epidermal interface alteration typically shows a superficial, sparse to mild lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Melanophages may be present in the subjacent papillary dermis and may be numerous in lesions involving darkly pigmented skin.

Lupus Erythematosus

CLINICAL FEATURES. Lupus erythematosus represents a spectrum of disease that can involve virtually any organ and shows a variable serologic profile (43,44). The etiology is unknown but is associated with autoantibodies and genetic factors. Clinically, lupus erythematosus exhibits a limited cutaneous discoid variant (DLE) and systemic variants including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). SLE is a systemic disease with protean manifestations. The classic cutaneous presentation is bilateral malar macular erythema. In contrast, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is characterized by the development of sharply circumscribed, erythematous plaques that may be either thick (hypertrophic) or thin (atrophic). Distinctive “carpet tack” follicular keratotic plugs may be present in the plaques. Both SLE and DLE tend to occur on areas exposed to sunlight, such as the face or dorsum of the hand. DLE lesions may precede, develop concomitantly with, or follow the appearance of SLE (44). Therefore, a histologic diagnosis of DLE does not eliminate the possibility that the patient may have SLE.

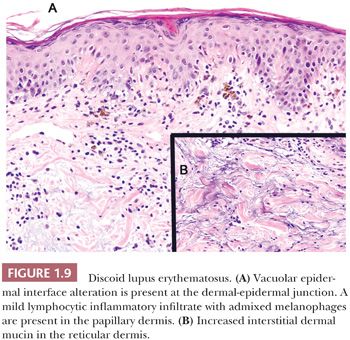

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The clinical variants of lupus erythematosus show similar findings that vary in degree and are characterized by vacuolar epidermal interface alteration, a perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, and increased interstitial dermal mucin (44,45). In DLE, the epidermis ranges from markedly acanthotic to atrophic. Both acanthosis and atrophy may be present in the same lesion. Hyperkeratosis is frequently marked, and it is usually parakeratotic. Flask-shaped plugs of the epidermal stratum corneum may fill the follicular orifices (follicular plugging). The degree of vacuolar interface change is variable, ranging from focal and relatively inconspicuous to diffuse and extensive (Fig. 1.9A). In older lesions, the basement membrane zone appears thickened and eosinophilic. Superficial and deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates in a perivascular and perifollicular distribution are usually present (44). The lymphocytic infiltrate may also encompass the eccrine glands and can extend into the subcutis. Biopsies of late-stage or quiescent lesions may show only a minimal to mild dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Increased interstitial dermal mucin is present in the reticular dermis in most cases and can be an important feature in differentiating lupus erythematosus from other diseases with vacuolar epidermal interface alteration. The presence of increased dermal mucin may not be readily evident in H&E-stained sections, so mucin stains, such as the colloidal iron and Alcian blue, can be helpful (Fig. 1.9B).

The histopathologic features are usually not as prominent in SLE as in DLE; however, distinction may be very difficult or impossible (44,45). The epidermis is of normal thickness or is slightly atrophic, and the stratum corneum is usually unaltered. Vacuolar epidermal interface alteration ranges from sparse to extensive. The perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is usually less dense and more superficial than in DLE. Often, the degree of mucin deposition in the reticular dermis is significantly greater than in DLE. In SCLE, the epidermis is usually atrophic and the inflammatory infiltrate is more superficial and often shows a focally lichenoid pattern (44).

Involvement of the subcutis shows nodular aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells and hyalinization and thickening of the adipocytic lobules. When the majority of the changes are limited to the subcutis, the process is termed lupus profundus (see lupus panniculitis).

The differential diagnosis of lupus erythematosus includes diseases characterized by vacuolar epidermal interface alteration, such as erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption, acute graft-versus-host disease, and dermatomyositis. With the exception of dermatomyositis, the presence of increased dermal mucin and a deep component of dermal inflammation in lupus erythematosus help to differentiate it from the other lesions with epidermal interface alteration. In addition to interface diseases, diseases that display a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, such as polymorphous light eruption (PMLE), can overlap with lupus erythematosus. The distinguishing features include epidermal interface alteration and increased dermal mucin in lupus erythematosus and extensive papillary dermal edema in PMLE.

Dermatomyositis/Polymyositis

CLINICAL FEATURES. Poorly demarcated, scaly, erythematous patches are found in dermatomyositis, a systemic disease that may affect the skin, striated muscles, and internal organs (46,47). A characteristic violaceous “heliotrope” erythema of the upper eyelids and extensor joint surfaces may be seen. Chronic patches can become poikilodermatous (atrophic and telangiectatic with pigmentary change). Pulmonary fibrosis and/or cardiac involvement are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality in patients with dermatomyositis. Dermatomyositis is also associated with internal malignancies (46,47).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The microscopic features of dermatomyositis are essentially indistinguishable from those of SLE. The epidermis is typically atrophic, and vacuolar interface change is usually prominent and extensive. A sparse, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and significantly increased dermal mucin are present in the dermis (48). The differential diagnosis is similar to lupus erythematosus (discussed earlier in the section “Lupus Erythematosus”) and includes both diseases with epidermal interface alteration and those with a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate.

Pityriasis Lichenoides

CLINICAL FEATURES. Pityriasis lichenoides encompasses a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic findings that have been grouped into pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA; also known as Mucha-Habermann disease) and pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) (49–51). PLEVA presents with the sudden onset of crops of small, ulcerated papules, mainly on the trunk, that may heal with superficial scarring (50,51). In contrast, PLC presents with red-brown papules that have a characteristic “waferlike” scale (49–51). In some patients, lesions of both types coexist. In rare cases, there is progression to lymphoma, usually mycosis fungoides (49,52). In addition, there can be clinical and histopathologic overlap with lymphomatoid papulosis, a CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (53,54).

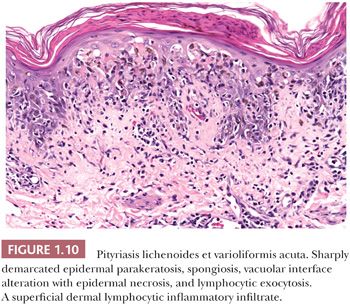

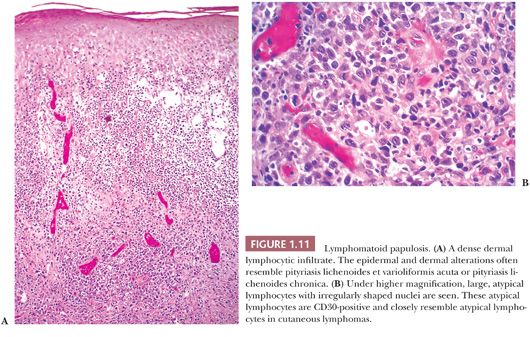

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Evolving lesions of PLEVA show focal to marked vacuolar epidermal interface alteration. The histologic counterpart of the ulcerated papules in PLEVA is a broad zone of full-thickness epidermal necrosis (50,51). The stratum corneum overlying the zone of necrosis is parakeratotic, and it may contain neutrophils (Fig. 1.10). Florid lymphocytic exocytosis, spongiosis, and erythrocyte extravasation into the epidermis are frequent. The associated lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis is dense and characteristically “wedge-shaped,” extending to the mid dermis. The broad base of the wedge extends along the epidermis. The dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is predominantly CD8-positive in PLEVA lesions (53,54). Occasional to scattered, large, CD30-positive lymphocytes may be present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate. In view of the CD30-positive lymphocytes in PLEVA, lymphomatoid papulosis (Fig. 1.11) is included in the differential diagnosis (54).

PLC is characterized by similar but less pronounced histopathologic features (49,50). A well-developed, sharply demarcated zone of parakeratosis is present. The degree of epidermal spongiosis, vacuolar interface alteration, and lymphocytic exocytosis is generally not as extensive as that seen in PLEVA and may be focal. The wedge-shaped pattern of the dermal inflammatory cells is usually present but more superficial and less dense, and CD4-positive lymphocytes predominate in lesions of PLC (55).

Pityriasis lichenoides can demonstrate a clonal T-cell population that can lead to confusion with lymphoproliferative lesions, and correlation with the clinical presentation is essential to establish an accurate diagnosis (52,55,56).

Acute and Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease

CLINICAL FEATURES. Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) affecting the skin classically occurs in the first 100 days following allogeneic bone marrow transplant. However, it may persist, recur or occur beyond 100 days post-transplant. It can also occur in patients receiving solid organ transplants and transfusions of nonirradiated blood or blood products in immunocompromised patients (57,58). It often presents on the acral surfaces and pinnae as an asymptomatic or slightly painful macular eruption. It may progress to a widespread morbilliform or erythrodermic eruption on the trunk and extremities that is difficult to distinguish clinically from a morbilliform drug eruption. Oral mucosal stomatitis and ulceration may be present (57).

Chronic GVHD generally occurs from 100 days after transplant but can be seen earlier. Overlapping clinical features of acute GVHD and chronic GVHD may be present (58). Two types of chronic GVHD—lichenoid and sclerodermoid—are generally observed (58,59).

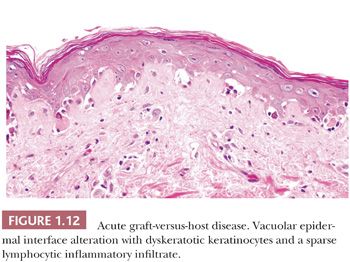

HISTOPATHOLOGY. In acute GVHD, the epidermis exhibits vacuolar interface alteration with associated dyskeratotic keratinocytes and rare to occasional intraepidermal lymphocytes (Fig. 1.12) (58). The degree of epidermal interface alteration ranges from very focal to extensive with full-thickness epidermal necrosis. In early lesions, vacuolar interface alteration may be very isolated and confined to the epidermal rete and hair follicle epithelium. The dermis displays a sparse, superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate. In skin biopsies from allogeneic bone marrow transplant patients, vacuolar epidermal interface alteration is not specific for GVHD and can also be associated with marrow ablative chemotherapy, cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, and radiation, requiring close clinical correlation for an accurate diagnosis (59).

The lichenoid form of chronic GVHD is similar to lichen planus, and the sclerodermoid variant closely resembles morphea and scleroderma, making clinical correlation essential (60).

Secondary Syphilis

CLINICAL FEATURES. Secondary syphilis can be a difficult clinical diagnosis because of its ability to mimic many other dermatoses (61–63). Asymptomatic, scaly, flesh-colored to erythematous papules or annular plaques are most frequently found on the face and trunk. Characteristic copper-colored macules may occur on the palms and soles. “Moth-eaten” alopecia on the scalp and mucous patches on the tongue are additional clues to the clinical diagnosis (62).

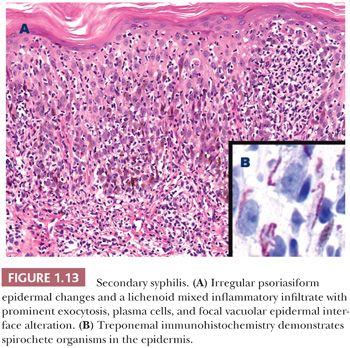

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The lesions of secondary syphilis range from an inconspicuous perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate to a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with vacuolar epidermal interface alteration (Fig. 1.13). Epidermal spongiosis, irregular psoriasiform acanthosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis are frequently present (61–63). The distribution of the inflammatory cell infiltrate is variable. It may be lichenoid, perivascular, superficial and deep, or diffuse and granulomatous. The granulomatous pattern is most frequently seen in chronic lesions. The presence of plasma cells in a cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrate should arouse suspicion of secondary syphilis if the clinical presentation is consistent. Plasma cells may be absent, sparse, or numerous in secondary syphilis. In addition, biopsies of papular lesions are preferred as macular lesions often show nonspecific features (61).

Silver impregnation stains, such as the Dieterle, Steiner, and Warthin-Starry stains, have traditionally been used to stain spirochetes. The organisms range from sparse to numerous and are best identified in the epidermis or perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Immunohistochemistry for Treponema pallidum is generally the preferred technique to demonstrate spirochete organisms in histologic sections (64).

ADJUNCTS TO MICROSCOPIC DIAGNOSIS. Correlation with treponemal serologic studies is recommended as they are generally positive in patients with secondary syphilis.

Fixed Drug Eruption

CLINICAL FEATURES. The term fixed drug reaction has its basis on the observation that the repeated administration of certain drugs results in the recurrence of a reddish-brown patch in the same location (65,66). Bullae may arise on the patch. Typical sites include the genitalia and face. Tetracyclines, barbiturates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and phenolphthalein are among the most common of many associated medications (65,66).

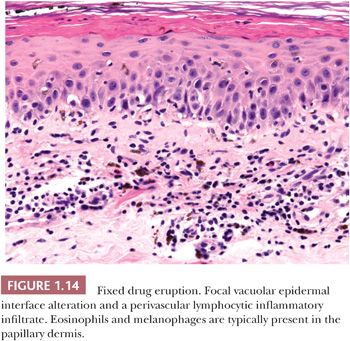

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Vacuolar epidermal interface alteration with scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes is characteristic of fixed drug eruptions (Fig. 1.14). Variable numbers of melanophages are typically present in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. In the superficial dermis, there is a perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate, often admixed with eosinophils (66). If a bulla is present, it is typically subepidermal and occurs in areas where the vacuolar interface alteration is most severe.

Erythema Multiforme

CLINICAL FEATURES. Erythema multiforme is a recurrent eruption characterized by a few to numerous erythematous plaques with urticarial features (67–70). The diagnostic clinical lesion resembles a target because of the alternating pale and erythematous rings. Other primary lesions in erythema multiforme include erythematous macules, papules, and bullae, explaining the use of the term multiforme. Any area of the skin may be involved, but the distal extremities, especially the palms and soles, and the mucosal surfaces are frequently affected. Although erythema multiforme may be idiopathic, it is commonly secondary to herpes simplex infections, Mycoplasma infections, and medications (67–70).

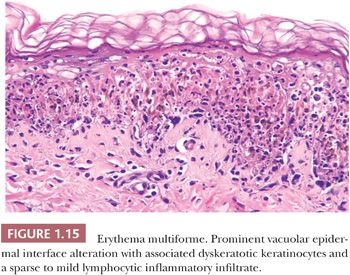

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The epidermal changes of erythema multiforme are virtually identical to those previously described for fixed drug eruption and show vacuolar epidermal interface alteration with associated intraepidermal dyskeratotic keratinocytes (Fig. 1.15) (68,70). The degree of vacuolar interface change ranges from focal to marked, and hemorrhagic subepidermal bullae may be present. The dermis displays a superficial, mild, predominantly lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with absent to occasional eosinophils. The epidermal changes are essential for the diagnosis, but the changes are not specific and must be correlated with the clinical presentation.

The differential diagnosis includes other diseases characterized by vacuolar epidermal interface alteration such as fixed drug eruption, acute GVHD, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis. The latter two connective tissue diseases can be distinguished from erythema multiforme by the presence of increased interstitial dermal mucin and a deep component of the dermal inflammatory infiltrate.

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

CLINICAL FEATURES. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are severe, potentially life-threatening mucocutaneous diseases once included in the erythema multiforme spectrum but are now considered to represent separate disorders (69–71). The clinical differentiation of SJS and TEN is based on the extent of skin and mucosal involvement. In general, SJS is defined as involvement of less than 10% of body surface area and TEN involves greater than 30% body surface area (72). In SJS, there are widespread erythematous macules; papules; large, flaccid bullae; and areas of desquamation involving the skin and mucosa. TEN shows similar features with more widespread desquamation and a mortality rate of 20% to 30% (73). The majority of cases of SJS/TEN are associated with medication, and the most commonly implicated drugs include sulfonamides, barbiturates, anticonvulsants, allopurinol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (69–71,73).

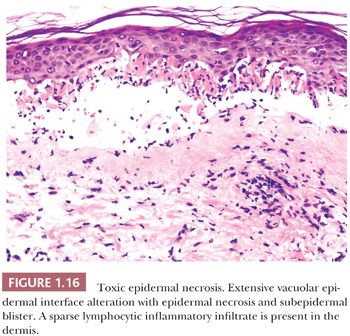

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Vacuolar epidermal interface alteration is the prototypical finding in both SJS and TEN (74). In early lesions, epidermal interface alteration may be patchy in distribution. In fully developed lesions of SJS and TEN, the epidermis shows extensive vacuolar interface alteration, often with full-thickness necrosis and subepidermal bullae (Fig. 1.16). The inflammatory cell component is generally sparse and predominantly lymphocytic.

It is important to recognize that TEN cannot be reliably distinguished from SJS and erythema multiforme by histopathologic findings alone and requires correlation with the clinical presentation to establish the diagnosis. TEN must be also differentiated from the clinically similar staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. As described, TEN is characterized by vacuolar epidermal interface alteration, often with full-thickness epidermal necrosis and subepidermal bullae. In contrast, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome exhibits a superficial plane of cleavage in the subcorneal or granular layer of the epidermis.

Verrucous Acanthosis: Verruca Vulgaris

This category encompasses several hamartomatous and neoplastic entities, such as epidermal nevus and seborrheic keratosis, in addition to verruca vulgaris. Verruca vulgaris is discussed in this chapter because it exemplifies the verrucous pattern of acanthosis.

Clinical Features. Common warts are typically exophytic verrucous papules that may be single lesions or that may be grouped in a linear configuration. Human papillomavirus is the etiologic agent (75).

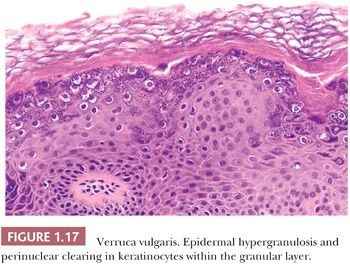

Histopathology. Striking upward displacement of the dermal papillae (papillomatosis) imparts a serrated appearance to the epidermis (75). The stratum corneum shows admixed hyperparakeratosis and hyperorthokeratosis with hypergranulosis and acanthosis (Fig. 1.17). Extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin may be found in the stratum corneum. Large, clumped keratohyalin granules may be present in the thickened granular layer. The dermal papillae show dilated vascular channels. A lymphocytic infiltrate of variable density is usually present in the upper dermis.

The differential diagnosis of verruca vulgaris includes seborrheic keratosis and epidermal nevus. The presence of admixed epidermal parakeratosis and orthokeratosis and dilated vascular channels in the dermal papillae are useful features to distinguish verruca vulgaris from histologic mimics.

Bullous and Pustular Diseases

The category of bullous and pustular diseases encompasses a large number of pathologically unrelated entities. The histopathologic classification of blistering disorders is classically based on the location of the plane of separation—subcorneal, intraepidermal, or subepidermal—and the presence or absence of associated findings, such as acantholysis and the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate. The intraepidermal blistering diseases are subdivided into those with and those without acantholysis. The subepidermal blistering diseases are subdivided into inflammatory and noninflammatory types. Because the definitive diagnosis of many blistering diseases is dependent on ancillary studies, such as immunofluorescence, the primary role of the pathologist is to determine the plane of separation, provide a differential diagnosis, and recommend appropriate ancillary diagnostic studies.

Subcorneal Bullae without Acantholysis

SUBCORNEAL PUSTULAR DERMATOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES. In subcorneal pustular dermatosis (also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease), large flaccid pustules form on the trunk and body folds (76,77). The disease generally affects middle-aged females, and there is an association with IgA paraproteinemia (78).

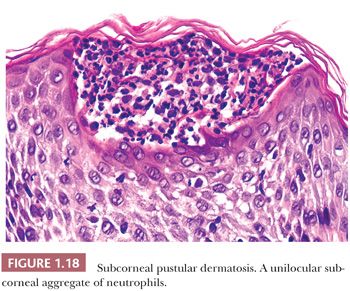

HISTOPATHOLOGY. A large, unilocular subcorneal aggregate of neutrophils is present (Fig. 1.18) (76,77). Neutrophils are also found in the subjacent epidermis, which may show psoriasiform acanthosis. A superficial, mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate composed primarily of neutrophils and lymphocytes is usually present (76,77).

The differential diagnosis of subcorneal pustular dermatosis includes pustular psoriasis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, bullous impetigo, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, pustular dermatophyte infection, pemphigus foliaceus, and the subcorneal type of IgA pemphigus. Clinical history and negative immunofluorescence studies are critical in establishing an accurate diagnosis.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is characterized by an acute onset of sterile, nonfollicular pustules, usually within hours of beginning a medication. Common associated agents include beta-lactam and macrolide antibiotics (79,80). The eruption resolves after cessation of the associated medication.

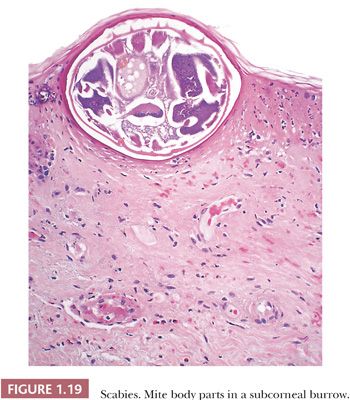

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Lesions of AGEP exhibit subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with associated spongiosis (79,80). The superficial dermis displays a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils. In addition, edema may be present in the papillary dermis. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may also be seen. Subcorneal neutrophils and an eosinophilic dermal infiltrate can also be seen in scabies infestation (Fig 1.19), and careful examination of multiple recut levels may be necessary to identify mite remnants.

The differential diagnosis of AGEP is similar to other subcorneal pustular disorders and includes pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, bullous impetigo, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, pustular dermatophyte infection, pemphigus foliaceus, and IgA pemphigus. In view of the broad histopathologic differential diagnosis, clinical correlation of disease onset with recent medication is critical in establishing the diagnosis.

Subcorneal Bullae with Acantholysis

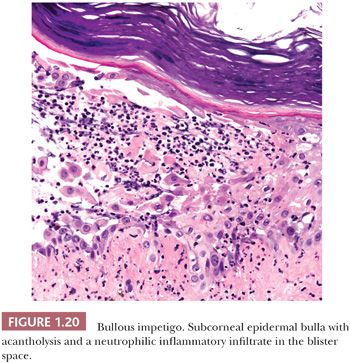

BULLOUS IMPETIGO

CLINICAL FEATURES. Found primarily in children, bullous impetigo consists of confluent pustules and honey-colored crusts. It usually is a result of a staphylococcal infection (81).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. The cleavage plane in bullous impetigo either is subcorneal or is within the upper stratum granulosum and contains a neutrophilic infiltrate (81). The roof of the blister is parakeratotic stratum corneum and the floor is formed of keratinocytes that may show focal acantholysis (Fig. 1.20).

STAPHYLOCOCCAL SCALDED SKIN SYNDROME

CLINICAL FEATURES. Infants and young children are generally affected and show diffuse erythema and superficial epidermal desquamation. A concurrent staphylococcal infection is present (82).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. A subcorneal or intragranular layer epidermal bulla with rare to focal acantholysis is the primary feature in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is generally sparse but can show a dense neutrophilic infiltrate.

The staphylococcal exfoliative toxins A and B target desmoglein 1, a desmosomal cell-cell adhesion molecule that is expressed in the upper levels of the epidermis (81). This correlates with the subcorneal localization of the bullae and epidermal acantholysis in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

The differential diagnosis includes pemphigus foliaceus, AGEP, pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, bullous impetigo, pustular dermatophyte infection, and the subcorneal type of IgA pemphigus. Correlation with the clinical history, microbiologic cultures, and immunofluorescence studies is essential for diagnosis.

Intraepidermal Bullae with Acantholysis

PEMPHIGUS. Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune blistering diseases that have the common feature of epidermal acantholysis (83). Based on the level of the cleavage plane, pemphigus foliaceus is classified as “superficial” type of pemphigus, whereas pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans are considered “deep” variants.

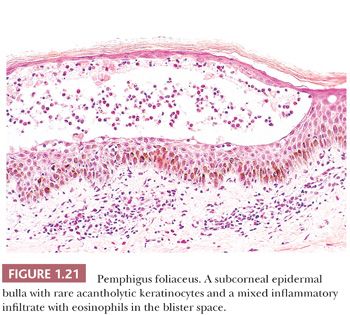

PEMPHIGUS FOLIACEUS

CLINICAL FEATURES. Pemphigus foliaceus is frequently not recognized clinically as a “blistering” disease because the bullae may be completely replaced by crusts and erosions by the time the patient seeks care. The trunk tends to be extensively involved. Mucous membrane involvement is rare (83–85). Pemphigus erythematosus is a variant of pemphigus foliaceus that is associated with lupus erythematosus (83).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Pemphigus foliaceus shows a subcorneal or intragranular layer epidermal blister with rare to focal acantholysis (Fig. 1.21) (84,85). A variable mixed inflammatory infiltrate is present ranging from sparse to densely neutrophilic. Eosinophils are frequently present in the adjacent epidermis and in the subjacent, sparse dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate.

The differential diagnosis includes AGEP, pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, bullous impetigo, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, pustular dermatophyte infection, and the subcorneal type of IgA pemphigus. Diagnosis is dependent on correlation with immunofluorescence studies.

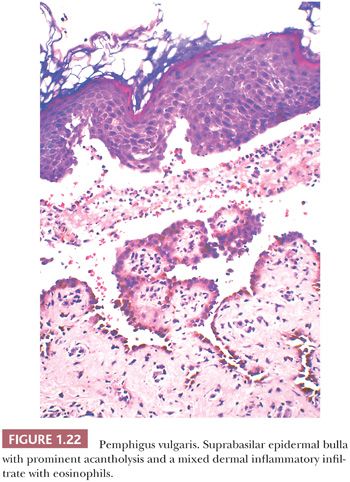

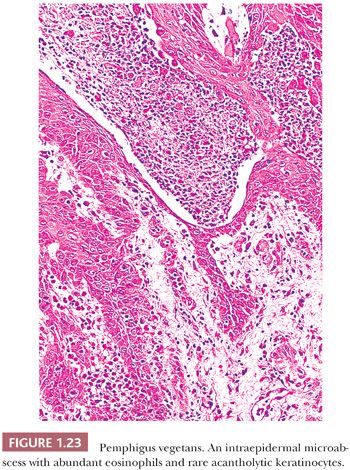

PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS, PEMPHIGUS VEGETANS, AND PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS

CLINICAL FEATURES. Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by numerous small, flaccid bullae present on the scalp and trunk, with the oral mucosa almost invariably involved at some time during the course of the illness, frequently as the presenting feature (83,86). The bullae rupture, leaving hemorrhagic erosions. Pemphigus vegetans is far less common than pemphigus vulgaris and exhibits verrucous plaques in flexural and intertriginous areas. Oral involvement is common (87). Paraneoplastic pemphigus presents with oral and cutaneous erosions and bullae in patients with an underlying neoplasm, usually a hematolymphoid malignancy (88,89).

HISTOPATHOLOGY. In pemphigus vulgaris, there is suprabasal epidermal acantholysis with an associated suprabasilar blister (83,86). The basal keratinocytes remain attached to the basement membrane to form a distinctive single row of cells that have been likened to a “row of tombstones” (Fig. 1.22). Extension of acantholysis into the follicular epithelium is frequently present. Rounded, acantholytic keratinocytes are usually present in the blister cavity. Eosinophilic spongiosis of the epidermis is common. The dermis displays a superficial, mixed inflammatory infiltrate with scattered to numerous eosinophils.

In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, epidermal acantholysis in pemphigus vegetans is often difficult to identify. In pemphigus vegetans, the epidermis typically exhibits marked acanthosis and hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses (Fig. 1.23) (86,87,90).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree