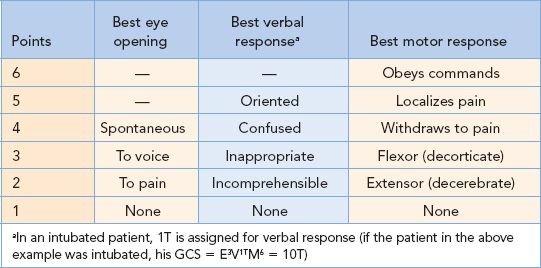

4 years of age

•Range of scores: 3 to 15 (extubated); 3T to 11T (intubated)

•Coma is defined as a GCS  8

8

A 60-year-old woman is struck by a motor vehicle and is brought to the emergency department by ambulance. On examination, her GCS is 6. The patient has no systemic injuries. A head CT scan demonstrates diffuse cerebral edema. What is the next step in the management of this patient?

Placement of an intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor.

Indications for Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

•GCS ≤ 8 after resuscitation and an abnormal head CT scan

•GCS ≤ 8 and a normal head CT scan but with ≥2 risk factors for intracranial hypertension, including age >40 years, SBP < 90 mmHg, and motor posturing

•Multi-system trauma with an altered level of consciousness where therapies for other injuries may have deleterious effects on ICP (i.e., high positive end-expiratory pressure, need for large volumes, etc.)

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

•Options include intraventricular catheters (IVCs), subarachnoid bolts, intraparenchymal monitors, and subdural and epidural catheters

•A major contraindication to ICP monitor placement is coagulopathy

•Normal ICP in adults is 10 to 15 mmHg

•Ketamine increases ICP and should be avoided in patients with head injury

Brain edema is greatest 2 to 3 days following a head injury.

Cerebral Blood Flow and Cerebral Perfusion Pressure

•Normal cerebral blood flow (CBF) is 50 to 55 mL per 100 g/min

•Impaired neural function occurs with CBF < 23 mL per 100 g/min

•Ischemic penumbra (cells can be functionally salvaged with return of blood flow) occurs at 8 to 23 mL per 100 g/min.

•Irreversible damage occurs at CBF < 8 mL per 100 g/min

•CBF is difficult to quantitate and is measured with a specialized equipment

•CBF depends on cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) which is related to ICP by the following equation

•CPP = MAP (mean arterial pressure) − ICP

•Normal CPP in adults is >50 mmHg

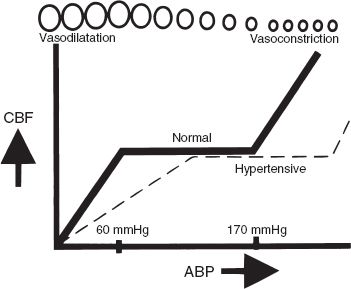

Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). Below 60 mmHg and above 170 mmHg, autoregulation of CPP breaks down. (With permission from O’Leary JP, Tabuenca A, eds. Physiologic Basis of Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.)

Goals of Therapy for Intracranial Hypertension

•ICP < 20 mmHg

•CPP ≥ 60 mmHg

•May see Cushing triad of hypertension, bradycardia, and respiratory irregularity

•Medical management includes elevation of the patient’s head, sedation/paralysis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage (when IVC utilized), osmotic therapy including mannitol and furosemide, hyperventilation (do not use prophylactically), barbiturate therapy, and hypothermia

•There is no role for steroids in head trauma

•The end result of uncontrolled intracranial hypertension is herniation

A unilaterally dilating pupil is the earliest sign of uncal herniation.

A 24-year-old man is brought to the emergency department following a motor vehicle crash with a GCS of 9. The patient’s head CT demonstrates a 1-cm epidural hematoma (EDH). What is the next step in the management of this patient?

Emergent surgical evacuation is indicated for an EDH in a patient with compromised mental status.

Epidural Hematoma

•Collection of blood between skull and dura

•Usually associated with a skull fracture

•Source of bleeding is usually arterial (middle meningeal artery)

•Classic presentation is a brief post-traumatic loss of consciousness, followed by a several hour “lucid interval” (observed in only one-third of cases), then subsequent obtundation, contralateral hemiparesis, ipsilateral pupillary dilation, coma, and death

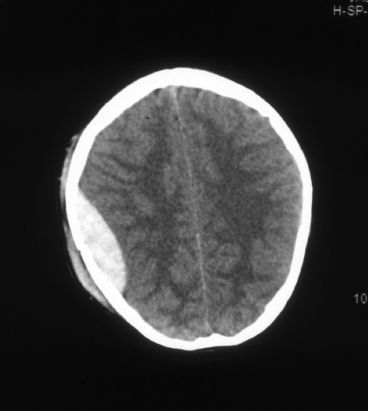

•Hyperdense biconvex (lenticular) shape on head CT scan

Epidural hematoma.

•Treatment is prompt surgical evacuation in most cases

•A small (<1 cm) EDH in an asymptomatic patient may resolve spontaneously and not require evacuation

The most common cause of an EDH is injury to the middle meningeal artery.

What is the usual source of bleeding in a subdural hematoma (SDH)?

Tearing of bridging cortical veins.

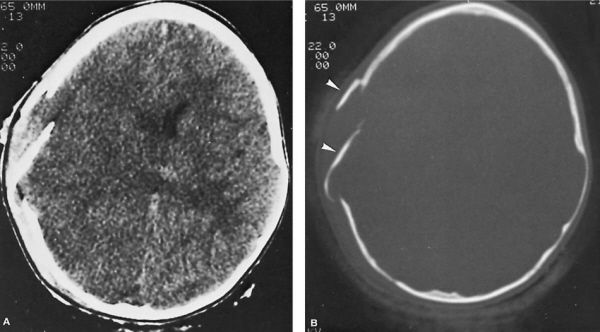

Subdural Hematoma

•Accumulation of blood between dura and underlying brain

•Usually due to torn bridging cortical veins

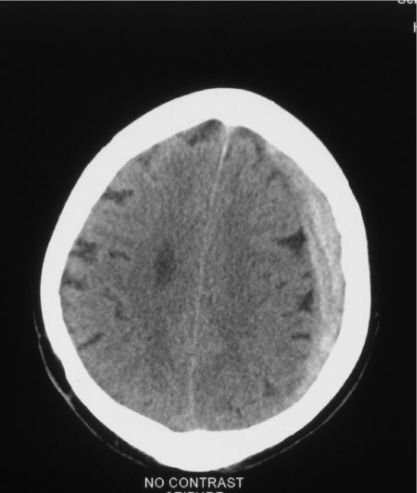

•Crescent shape on head CT scan

Subdural hematoma.

•With time, these lesions undergo clot lysis, organization, and neomembrane formation

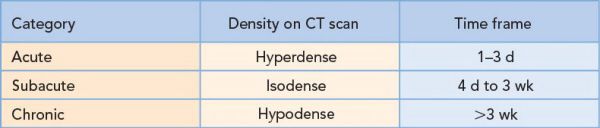

•Density of the lesion changes with time:

•Mortality for acute SDH is greater than for an EDH

•Treatment is surgical evacuation for symptomatic SDH greater than 1 cm (at its thickest point)

A 20-year-old man is ejected during a high-speed motor vehicle crash. On arrival, he is hemodynamically stable with a GCS of 5T. His initial head CT is significant for a small left parietal traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). His neurologic examination and repeat head CT scan the following day remain unchanged. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Diffuse axonal injury.

•Most common traumatic brain injury

•Axonal shearing injury

•Induced by sudden acceleration/deceleration or rotational forces

•Responsible for severely impaired neurologic function in patients without gross parenchymal contusions or hematomas

•Initial head CT scans are often normal

•Most common finding on MRI is multifocal hyperintense foci on T2-weighted images

•Punctate hemorrhages occur at the gray-white matter interface, corpus callosum, upper brainstem and superior cerebellar peduncle

•Histology reveals axonal swelling, disruption of axons and retraction balls (swollen proximal ends of severed axons)

Cerebral Contusion

•Second most common traumatic brain injury

•Induced by the brain striking an osseous ridge (or less frequently a dural fold) and occurs when differential acceleration/deceleration forces are applied to the head

•Common locations are the temporal lobes (50%), frontal lobes (30%), and parasagittal/convexity

•Initial head CT scan findings include patchy, ill-defined, low-density lesions that may be mixed with hyperdense foci of hemorrhage

•Serial CT scans may show more and/or larger lesions and delayed hemorrhages

A 40-year-old female is brought to the emergency department with an initial GCS of 15. On examination, she has bilateral periorbital ecchymoses and a small amount of clear fluid dripping from her nose. Her head CT scan demonstrates a basilar skull fracture. What is the initial management of this patient?

Conservative management (surgery is not indicated).

Basilar Skull Fracture

•Presents with CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea, hemotympanum, postauricular ecchymoses (Battle’s sign), periorbital ecchymoses (raccoon’s eyes), and cranial nerve injuries

•Nasogastric tube placement is contraindicated in trauma patients with suspected basilar skull fractures

•Most do not require further treatment

Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistula

•Trauma is the most common cause (other causes include post-procedure and spontaneous)

•Occurs in about 2% of patients with head injury

•70% occur with 48 hours of injury and 98% are clinically evident by 3 months

•Complications include meningitis (25%) and pneumocephalus (25%)

•Diagnosis of traumatic CSF fistula

•Fluid is clear

•Target sign

•Performed when a CSF leak is suspected but fluid is blood tinged

•Fluid is placed on a piece of filter paper or absorbent cloth

•If CSF is present, a “halo sign” will form as the CSF content of the fluid migrates farther out

•The final product looks like a bull’s eye with the thicker blood or mucus in the center and the lighter-colored CSF migrating beyond the inner ring

•Presence of beta-2 transferrin, a substance only found in CSF, perilymph, and vitreous humor of the eye

•Neuroimaging techniques, including fine-cut CT with coronal and axial images, contrast or radionuclide cisternography and nasal endoscopsy, can be helpful in diagnosis

•Treatment of traumatic CSF fistula

•70% resolve within 7 days with conservative treatment (head-up in bed, bowel regimen to avoid straining, avoidance of maneuvers that increase ICP such as nose blowing, coughing, sneezing)

•For persistent leaks, lumbar puncture (LP) or lumbar drainage may be beneficial

•Surgical repair is rarely necessary

A 6-year-old child is brought to the emergency department after a fall from his bike with transient loss of consciousness. On examination, he is awake, interactive, and appropriate. A head CT scan demonstrates a 3-cm linear nondisplaced skull fracture in the right parietal region; there is no underlying brain abnormality. Does this fracture need operative fixation?

Operative fixation is not indicated in this case.

Criteria for Surgery for a Depressed Skull Fracture

•Depth of depressed fracture > width of surrounding bone (closed depressed skull fractures in a neurologically intact patient overlying a dural sinus may be managed conservatively)

•Open fracture

Depressed skull fracture. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•Fracture associated with a significant underlying intracranial hematoma that requires evacuation

•Fracture over cosmetic areas

A mother brings her 15-month-old daughter to the emergency department because of lethargy. The mother states the infant accidentally fell off a 5-foot-tall changing table onto the floor. On examination, the child has numerous bruises. Ophthalmologic examination reveals retinal hemorrhages. Skull X-rays demonstrate a linear skull fracture and a small chronic SDH. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Child abuse should be suspected.

Cranial Findings Associated with Child Abuse

•Retinal hemorrhages

•Bilateral chronic SDHs

•Multiple skull fractures

A patient develops hyponatremia while on the floor and is found to have syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). His neurologic examination is unchanged. What is the first step in management?

The mainstay of treatment for SIADH is fluid restriction.

Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion

•Release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) in the absence of physiologic stimuli

•Etiologies

•Intracranial processes (stroke, hemorrhage, trauma, tumors, SAH, post craniotomy, infection)

•Tumors (small cell carcinoma of the lung, carcinoma of the pancreas and duodenum)

•Drugs (chlorpropamide, carbamazepine, vincristine, vinblastine)

•Infectious pulmonary diseases (tuberculosis, pneumonia)

•Idiopathic

•Symptoms are secondary to hyponatremia (confusion, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, restlessness, irritability, seizure, and coma)

•Patients are usually euvolemic, but may be hypervolemic (pitting edema is almost always absent)

•Diagnosis

•Hyponatremia

•Low serum osmolality

•High urine sodium

•Normal renal, adrenal, and thyroid functions

•No signs of dehydration or fluid overload

•Water load test if diagnosis unclear

•Treatment

•Mild/asymptomatic SIADH: Fluid restriction

•Severe or symptomatic SIADH: Fluid restriction, hypertonic saline, furosemide

•Chronic SIADH: Fluid restriction, demeclocycline (tetracycline antibiotic that partially antagonizes the effects of ADH on renal tubules), furosemide

•Renal loss of sodium as a result of intracranial disease (especially SAH), causing hyponatremia and a decrease in extracellular fluid volume

•Laboratory values may be identical with SIADH and cerebral salt wasting (CSW)

•Difference between SIADH and CSW is volume status (patients with CSW are hypovolemic)

•Treatment is volume replacement and positive salt balance

Central pontine myelinolysis may result from excessively rapid correction of hyponatremia.

Central or Neurogenic Diabetes Insipidus

•Due to decreased release of ADH (in contrast to nephrogenic diabetes insipidus which is due to renal resistance to normal or supranormal levels of ADH)

•Caused by neoplastic or infiltrative lesions of the hypothalamus or pituitary, pituitary surgery, and severe head injuries

•Symptoms include polyuria, polydypsia, and excessive thirst

•Diagnosis is based on:

•Hypernatremia

•High urine output (>250 cc/hour)

•Low urine specific gravity

•Water deprivation test if diagnosis is unclear

•Treatment is vasopressin

A 70-year-old man is brought to the emergency department following a fall in which he struck his forehead. On physical examination, he has a large forehead laceration. Neurologic examination is significant for bilateral weakness in the upper extremities greater than the lower extremities, decreased sensation over the shoulders and arms and urinary retention. Cervical spine X-rays demonstrate no fracture or subluxation. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Acute central cervical spinal cord injury.

Types of Spinal Cord Injury

•Complete: No preservation of any motor or sensory function below the level of injury

•Incomplete: Any residual motor or sensory function below the level of injury

•Acute central cervical spinal cord injury

•Anterior cord syndrome

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree