Male Genital and Reproductive Function

Marvin Van Every

Key Questions

• What is the role of Sertoli cells in spermatogenesis?

• What is the function of Leydig cells?

• Which branch of the autonomic nervous system is responsible for penile erection? Ejaculation?

• Which genitourinary structures develop embryologically from the wolffian ductal system in males?

• How do the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadotropic hormones influence male reproductive function?

• How do the processes of capacitation and acrosome reaction affect the fertilization process?

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Copstead/

This chapter provides a foundation for comprehending male genital and reproductive disorders, which are presented in Chapter 31. The anatomy and embryology of the male genitourinary tract—those organs involved in the processes of sexual reproduction and elimination of nitrogenous wastes—will be presented first. Because these organs are derived from common embryologic structures, the anatomy and embryology of the male genitalia and urinary system will be emphasized, and the differences in embryologic development between males and females will be considered when pertinent. The remainder of this chapter will deal with the physiologic processes of male reproduction.

Anatomy

Upper Genitourinary Tract

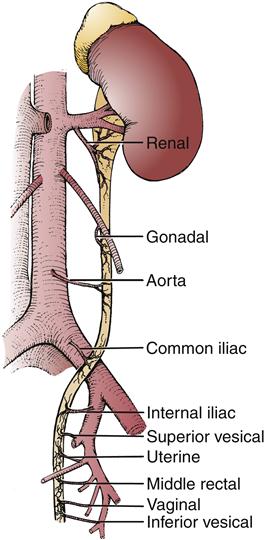

The upper genitourinary tract consists of the kidneys and ureters. The kidneys receive their blood from the renal arteries, which arise directly from the aorta. They are usually solitary but will at times be duplicated. The ureteral blood supply is derived from multiple sources. The renal pelvis and upper part of the ureter receive blood from branches of the renal artery. The arterial blood supply of the middle ureter segment comes from the internal spermatic artery (gonadal artery), and the lowermost ureter sections receive blood from the branches of the common iliac, internal iliac, and vesical arteries (Figure 30-1). The veins of the renal pelvis and ureter are usually paired with the arteries.

Lower Genitourinary Tract

Bladder

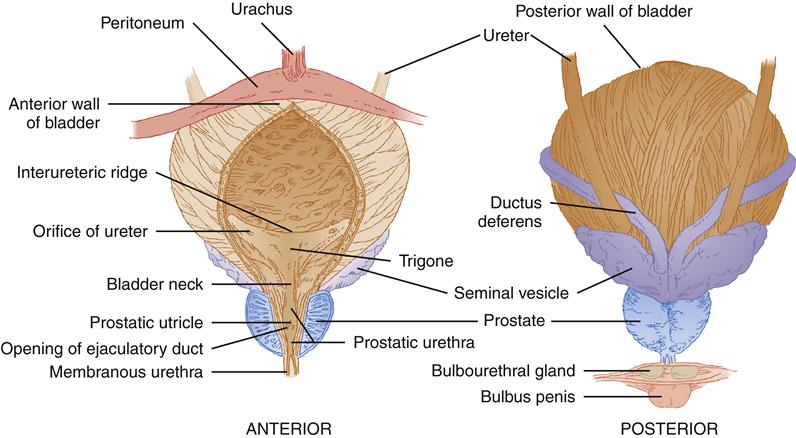

The bladder is a hollow muscular organ that serves as a reservoir for urine. The adult bladder normally has a capacity of 450 to 500 ml. When empty, the bladder lies behind the pubic symphysis and is mainly a pelvic organ. With overdistention or chronic urine retention, the abdomen may bulge, allowing easy palpation of the bladder in the suprapubic region.

The ureters enter the bladder posteroinferiorly. The ureteral orifices are situated on a crescent-shaped ridge and are approximately 2.5 cm apart. The triangular area demarcated by this interureteric ridge and bladder neck is called the trigone (Figure 30-2). As will be discussed later in the chapter, the trigone has a different embryologic origin from the rest of the bladder body, or fundus. The trigone is composed of mesoderm, and the fundus is composed of endoderm.

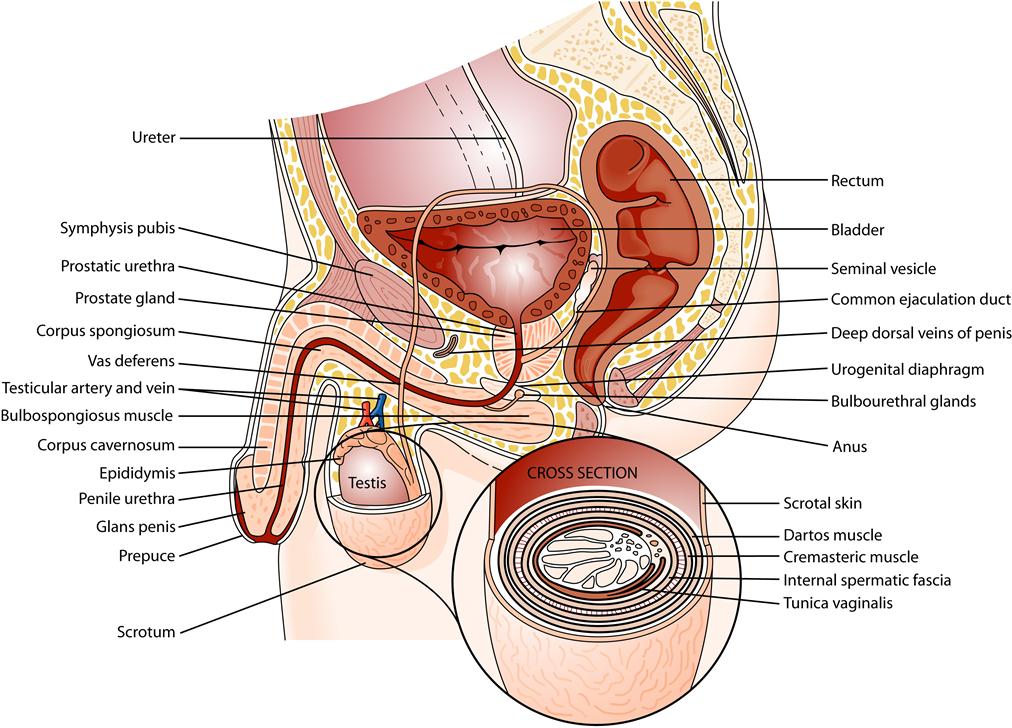

In males, the bladder lies anterior to the seminal vesicles, vasa deferentia, ureters, and rectum. The dome and part of the posterior bladder surfaces are covered by peritoneum and are thus in close proximity to the small bowel and the sigmoid colon. The neck of the bladder, which is the most inferior part, leads to the urethra. In males, the prostate lies between the bladder and the muscle layers of the pelvic floor that composes the urogenital diaphragm.

The arterial blood supply of the bladder comes from the superior, middle, and inferior vesical arteries, which originate from the anterior division of the hypogastric artery. Venous drainage occurs by a rich plexus of veins that surround the bladder and ultimately drain into the hypogastric veins.

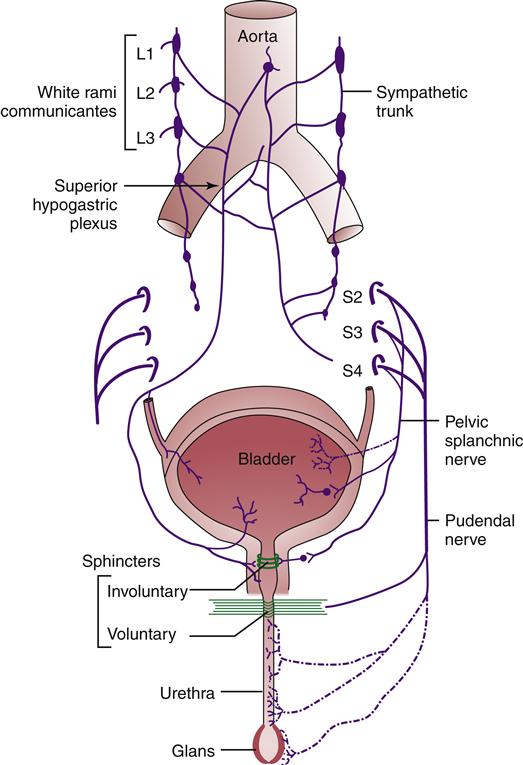

The bladder and urethra receive their nerve supply from both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic fibers, originating mainly from the lower thoracic and upper lumbar segments (T11-T12 and L1-L2), innervate the bladder and urethra as the hypogastric nerves. These sympathetic fibers are distributed more densely in the bladder base and proximal end of the urethra than in the bladder dome. The sympathetic nerves facilitate storage of urine. Studies have revealed differences in the bladder muscle receptors, with cholinergic receptors concentrated in the fundus and adrenergic receptors present in the trigone and proximal end of the urethra (Figure 30-3).

The parasympathetic nerve supply originates from the sacral segments (S2-S4), which proceed to form a plexus surrounding the bladder. In the male, a separate segment will reach the prostate and form the prostatic plexus. From this plexus, nerves emerge to innervate the erectile tissue of the male penis and the clitoris of the female (see Figure 30-3).

Branches of the bladder plexus penetrate the muscular coat of the bladder and become distributed throughout the detrusor. Parasympathetic muscle receptors are cholinergic in nature, and parasympathetic stimulation induces a detrusor contraction that causes bladder emptying.

Urethra

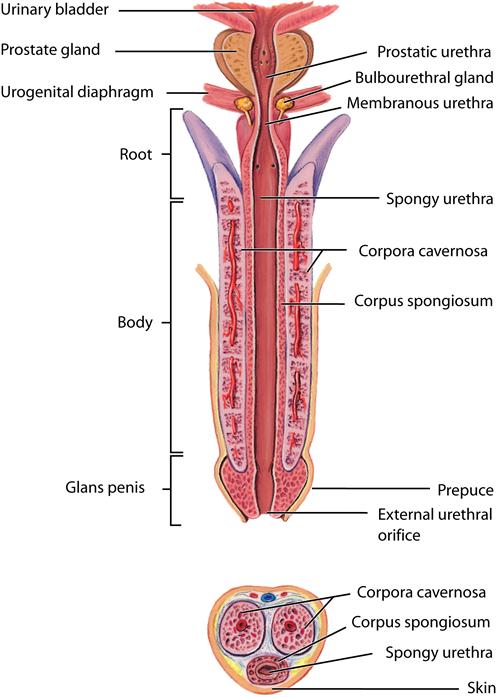

The male urethra, which extends from the bladder to the external opening (urethral meatus) at the tip of the penis, functions as a conduit for both urinary and genital systems. It is commonly divided into three segments: the prostatic, the membranous, and the penile or spongy urethra (Figure 30-4).

Auxiliary Genital Glands

The auxiliary genital glands of the male consist of the prostate, the seminal vesicles, and the bulbourethral glands. These glands secrete products that contribute to the seminal fluid.

Prostate

The prostate lies below the bladder and has both a muscular and a glandular component. The normal prostate weighs about 20 g and measures about 3.5 cm transversely and about 2.5 cm in its vertical and anteroposterior dimensions. The prostate is conical and is anterior to the rectum. Its base is continuous with the bladder neck, and the inferior aspect of the prostate gland, or apex, lies adjacent to the urogenital diaphragm (Figure 30-5).

The prostate consists of a thin fibrous capsule with internally circular smooth muscle fibers and collagenous tissue that surround the urethra. Deep in this layer of connective and elastic tissue lies the prostatic stroma, which contains the prostatic epithelial glands. These glands drain into excretory ducts, which open chiefly on the floor of the urethra between the verumontanum and the vesical neck. The prostate is primarily a reproductive organ. In conjunction with the seminal vesicles, the prostate produces the fluid that supports the sperm. In fact, the sperm constitute a small amount of the semen with the vast majority of the seminal fluid coming from the prostate and seminal vesicles. A further function of the prostate gland is to act as a valve for the bladder.

The main blood supply of the prostate is derived from the inferior vesical artery, a branch of the hypogastric artery. Besides the prostate, this artery also supplies the distal portion of the ureter, the seminal vesicles, and part of the bladder. A complex plexus situated between the prostate and overlying tissue freely communicates with the inferior hypogastric veins and provides venous drainage to the prostate.

Seminal Vesicles

The seminal vesicles are paired organs that lie next to the prostate under the base of the bladder (see Figure 30-5). Their coiled pouches secrete a fluid important to the survival of spermatozoa.

Bulbourethral Glands

The bulbourethral or Cowper glands are located on each side of the membranous urethra within the urogenital diaphragm. They add a mucoid secretion to the semen.

External Genitalia

Scrotum

The scrotum (see Figure 30-5) is a pouchlike sac that lies below the penis and pubic symphysis. A septum of connective tissue divides the sac into two compartments. Each compartment contains a male gonad, or testis, with its associated epididymis and the lower portion of the vas deferens protected by the spermatic cord and its coverings. The scrotum not only supports the testes but also, by relaxation and contraction of its muscular layer, helps regulate temperature of the testes.

The scrotal sac consists of several tissue layers. The scrotal skin overlies the dartos muscle layer, whose smooth muscle fibers are embedded in loose connective tissue. The dartos muscle functions to contract the scrotal pouch when cold and expand it when warm. Under the dartos layer are several fascial layers (see Figure 30-5) that are continuous with the muscular layers of the abdominal wall and make up the covering of the spermatic cord. The external spermatic fascia is continuous with the external oblique aponeurosis of the abdominal wall. A few slips of skeletal muscle derived from the internal oblique muscle layer make up the cremasteric muscle, which adds to the upper part of the cord. The internal spermatic fascia is a continuation of the transverse fascia of the abdominal wall, with the transversus abdominis muscle not contributing to the cord layers. Finally, the peritoneum provides the tunica vaginalis layers, which are actually separated from the abdominal cavity by obliteration of the processus vaginalis.

The scrotum receives its blood supply from the external pudendal artery, a branch of the femoral artery. In addition, the scrotum receives blood from portions of the internal pudendal artery (a branch of the hypogastric artery) and the cremasteric and testicular arteries that transverse the spermatic cord.

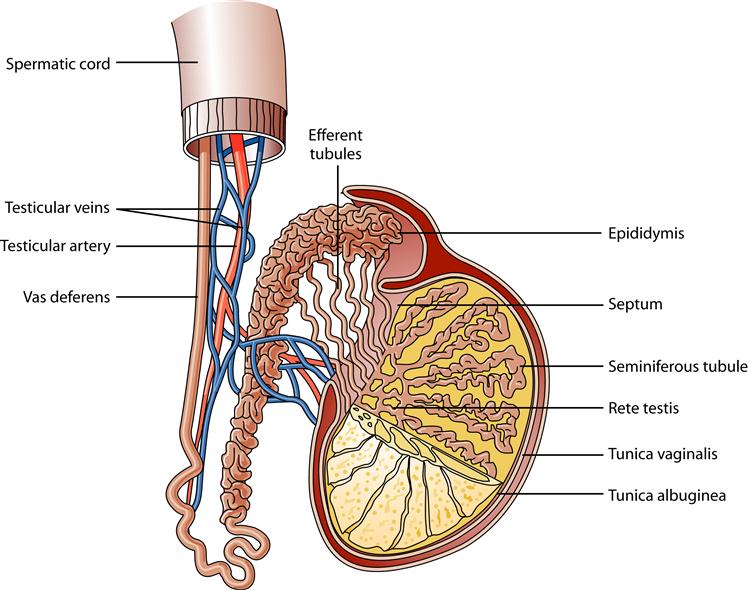

Testes

The testes are the male reproductive organs responsible for sperm production. They average about 4 to 5 cm in length and 2 to 3 cm in thickness. The testes lie within the scrotum and are suspended by the spermatic cord. The testes are covered by a thick fascial layer called the tunica albuginea. This layer invaginates posteriorly to form the mediastinum testis. This fibrous mediastinum sends fibrous septa into each testis that separate it into many different lobules. Each lobule contains one to four seminiferous tubules that if stretched to full length would measure approximately 60 cm. Spermatozoa production occurs within the epithelial lining of the seminiferous tubules (Figure 30-6).

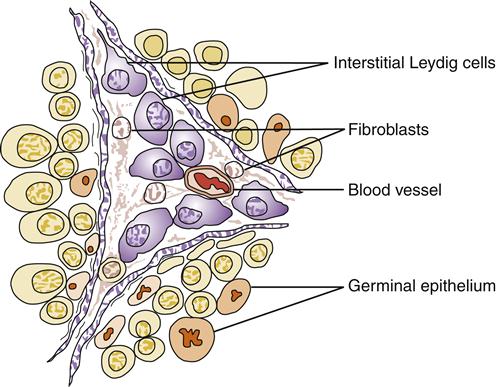

The seminiferous tubules have a basement membrane consisting of elastic and connective tissue that supports the seminiferous cells. The seminiferous cells are either Sertoli cells (supporting cells) or spermatogenic cells. Found between the seminiferous tubules and embedded in connective tissue, the interstitial Leydig cells produce and secrete testosterone, a hormone involved in the development of male sexual characteristics (Figure 30-7). The seminiferous tubules converge on the mediastinum testis. The tubules, which are connected by the straight efferent ducts, drain into the head of the epididymis.

The testicular blood supply is derived from the internal spermatics, which arise directly from the aorta below the renal arteries. They course inferiorly through the spermatic cord and anastomose with the cremasteric arteries and the arteries of the vas; these vessels also contribute to the blood supply. The blood from the testis returns through a plexus of veins in the spermatic cord (the pampiniform plexus) that forms the spermatic veins. The left internal spermatic vein enters the left renal vein, which subsequently enters the vena cava. The right internal spermatic vein enters the vena cava directly.

Epididymis and Ductus Deferens

The epididymis is a tightly coiled tube that lies along the top of and behind each testis. It is divided into the head, situated at the upper pole of the testes; the body, lying posterior to the testes; and the tail, which is attached to the inferior pole of the testes (see Figure 30-6). The body and the tail of the epididymis form one continuous tube that serves as a conduit for maturing spermatozoa. In the epididymis, sperm develop the ability to swim.

As the convoluted tube of the tail leaves its testicular attachments, it increases in diameter to become a thick, muscular tube called the ductus deferens, also called the vas deferens. Leaving the spermatic cord, the vas deferens follows an extraperitoneal course and passes caudally and laterally along the pelvic wall. As it passes medial to the distal end of the ureter, it bends caudally to reach the midline and lies on the posterior wall of the bladder just medial to the seminal vesicles. It terminates in a dilated ampulla that courses underneath the base of the prostate. At this point the duct of the seminal vesicle joins with the duct of the ampulla, and the ejaculatory duct is formed. The ejaculatory ducts open in the prostatic urethra at the level of the verumontanum.

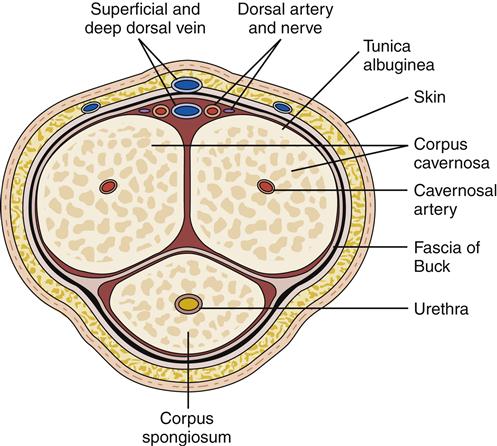

Penis

The penis is the male organ of copulation and urinary excretion. It is composed of three erectile bodies—two paired corpora cavernosa, which lie dorsally, and the corpus spongiosum, which contains the urethra (Figure 30-8). Grossly, the penis is divided into three segments. The root of the penis consists of the proximal ends of the corpora cavernosa, which attach to the pelvic bones, and the proximal end of the corpus spongiosum, which connects to the undersurface of the urogenital diaphragm. Together these attachments provide fixation and stability to the penis. The shaft or body of the penis consists of all three erectile bodies: the two cavernous bodies lying on the dorsum, and the corpus spongiosum, which occupies a depression on their ventral surface. Finally, the glans of the penis forms the distal segment of the corpus spongiosum (see Figure 30-4).

The three erectile bodies have the capability to become engorged with blood and enlarge considerably with erection. Microscopically, these bodies have an internal spongelike network that consists of endothelium-lined spaces surrounded by smooth muscle.

Each corpus is enclosed in a fascial sheath, the tunica albuginea, and all are subsequently surrounded by a thick fibrous envelope known as the fascia of Buck. The overlying skin of the penis is remarkable for its thinness and looseness of connection with the fascial sheath of the penis. The skin of the penis is folded upon itself to form the prepuce, or foreskin. It is this penile skin overlying the glans that is removed with circumcision.

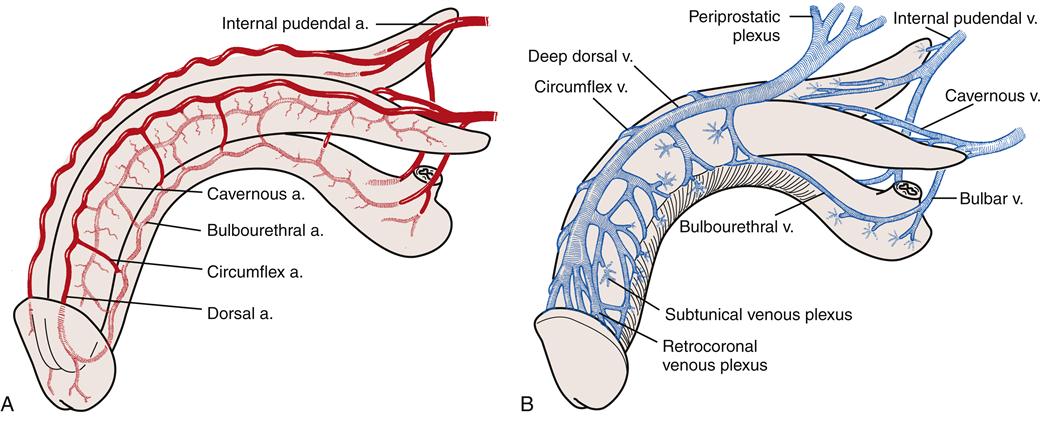

The arterial blood supply is primarily derived from the paired internal pudendal arteries, which are branches of the hypogastric arteries. Each internal pudendal artery branches several times in the penis. The deep or cavernous artery supplies the entire corpus cavernosum. The urethral artery supplies the corpus spongiosum, and the bulbar artery supplies the bulb of the corpus spongiosum. The dorsal artery continues along the dorsum of the penis and lies below the fascia of Buck and between two dorsal veins. It provides additional supply to the glans (Figure 30-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree