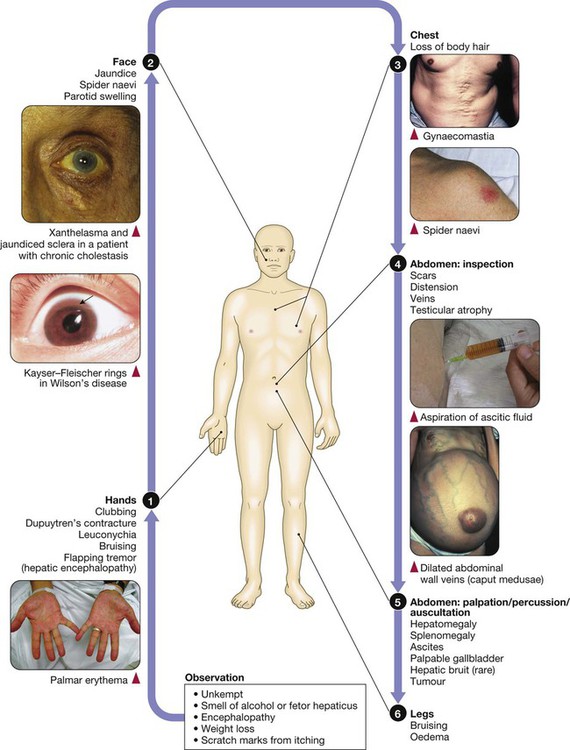

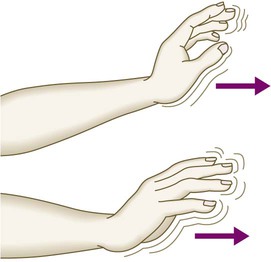

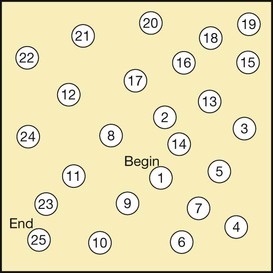

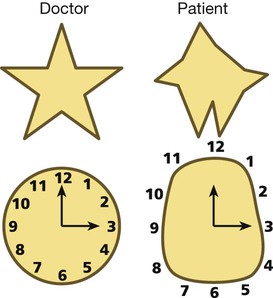

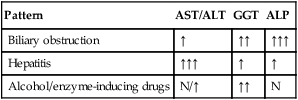

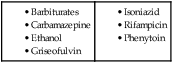

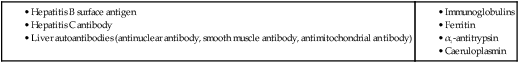

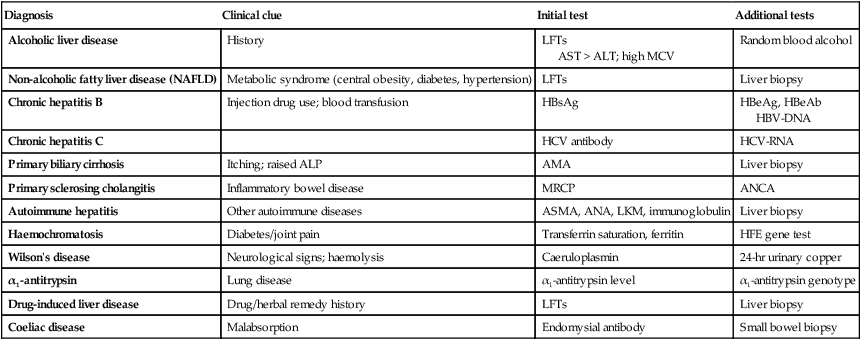

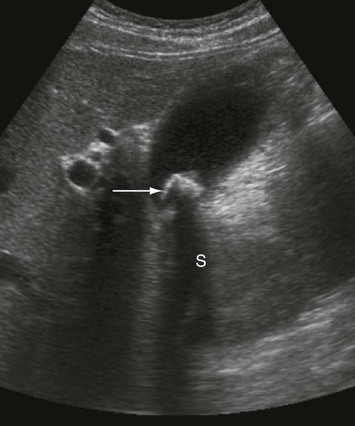

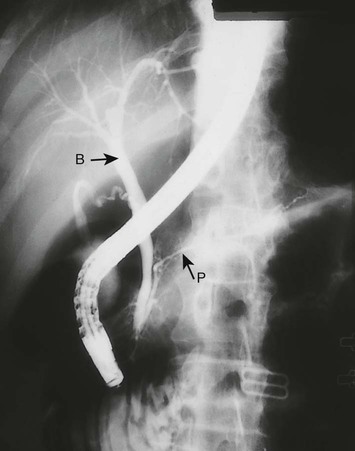

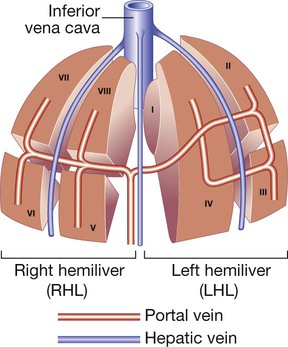

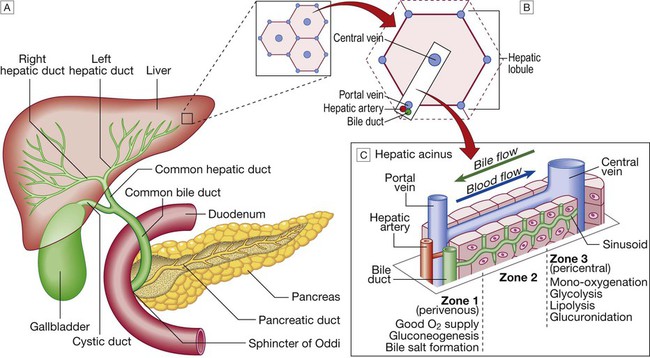

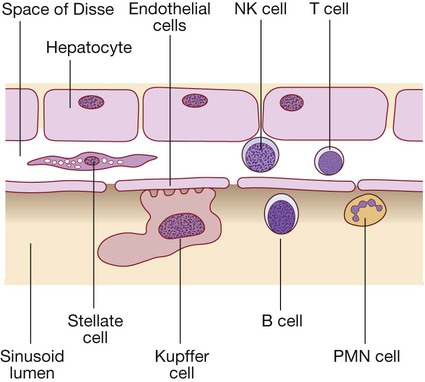

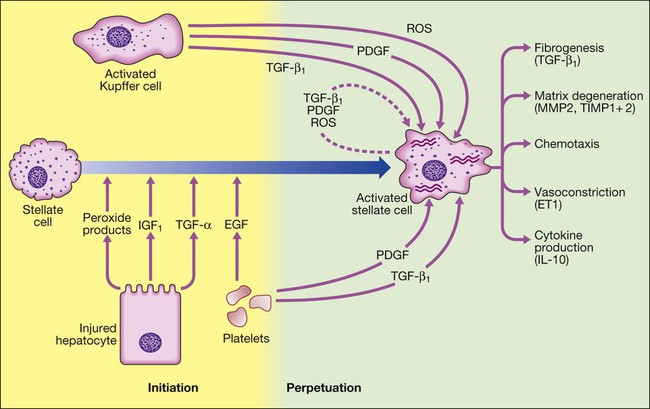

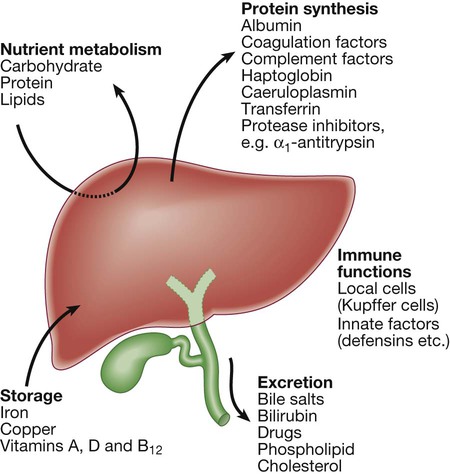

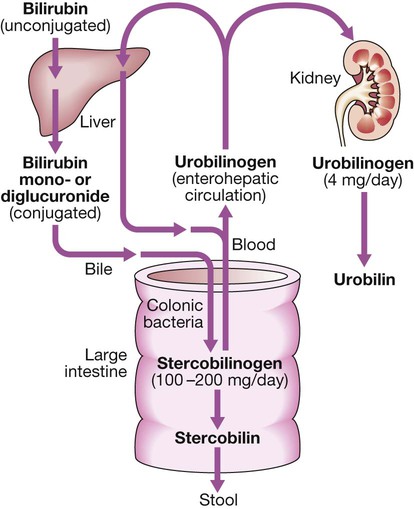

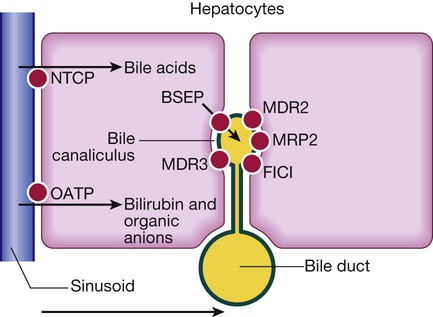

The liver weighs 1.2–1.5 kg and has multiple functions, including key roles in metabolism, control of infection, elimination of toxins and by-products of metabolism. It is classically divided into left and right lobes by the falciform ligament, but a more useful functional division is into the right and left hemilivers, based on blood supply (Fig. 23.1). These are further divided into eight segments according to subdivisions of the hepatic and portal veins. Each segment has its own branch of the hepatic artery and biliary tree. The segmental anatomy of the liver has an important influence on imaging and treatment of liver tumours, given the increasing use of surgical resection. A liver segment is made up of multiple smaller units known as lobules, comprised of a central vein, radiating sinusoids separated from each other by single liver cell (hepatocyte) plates, and peripheral portal tracts. The functional unit of the liver is the hepatic acinus (Fig. 23.2). Endothelial cells line the sinusoids (Fig. 23.3), a network of capillary vessels that differ from other capillary beds in the body in that there is no basement membrane. The endothelial cells have gaps between them (fenestrae) of about 0.1 micron in diameter, allowing free flow of fluid and particulate matter to the hepatocytes. Individual hepatocytes are separated from the leaky sinusoids by the space of Disse, which contains stellate cells that store vitamin A and play an important part in regulating liver blood flow. They may also be immunologically active and play a role in the liver’s contribution to defence against pathogens. The key role of stellate cells in terms of pathology is in the development of hepatic fibrosis, the precursor of cirrhosis. They undergo activation in response to cytokines produced following liver injury, differentiating into myofibroblasts, which are the major producers of the collagen-rich matrix that forms fibrous tissue (Fig. 23.4). Hepatocytes provide the driving force for bile flow by creating osmotic gradients of bile acids, which form micelles in bile (bile acid-dependent bile flow), and of sodium (bile acid-independent bile flow). Bile is secreted by hepatocytes and flows from cholangioles to the biliary canaliculi. The canaliculi join to form larger intrahepatic bile ducts, which in turn merge to form the right and left hepatic ducts. These ducts join as they emerge from the liver to form the common hepatic duct, which becomes the common bile duct after joining the cystic duct (see Fig. 23.2). The common bile duct is approximately 5 cm long and 4–6 mm wide. The distal portion of the duct passes through the head of the pancreas and usually joins the pancreatic duct before entering the duodenum through the ampullary sphincter (sphincter of Oddi). It should be noted, though, that the anatomy of the lower common bile duct can vary widely. Common bile duct pressure is maintained by rhythmic contraction and relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi; this pressure exceeds gallbladder pressure in the fasting state, so that bile normally flows into the gallbladder, where it is concentrated tenfold by resorption of water and electrolytes. The liver plays a central role in carbohydrate, lipid and amino acid metabolism, and is also involved in metabolising drugs and environmental toxins (Fig. 23.5). An important and increasingly recognised role for the liver is in the integration of metabolic pathways, regulating the response of the body to feeding and starvation. Abnormality in metabolic pathways and their regulation can play an important role both in liver disease (e.g. non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)) and in diseases that are not conventionally regarded as diseases of the liver (such as type II diabetes mellitus and inborn errors of metabolism). Hepatocytes have specific pathways to handle each of the nutrients absorbed from the gut and carried to the liver via the portal vein. • Amino acids from dietary proteins are used for synthesis of plasma proteins, including albumin. The liver produces 8–14 g of albumin per day, and this plays a critical role in maintaining oncotic pressure in the vascular space and in the transport of small molecules like bilirubin, hormones and drugs throughout the body. Amino acids that are not required for the production of new proteins are broken down, with the amino group being converted ultimately to urea. • Following a meal, more than half of the glucose absorbed is taken up by the liver and stored as glycogen or converted to glycerol and fatty acids, thus preventing hyperglycaemia. During fasting, glycogen is broken down to release glucose (gluconeogenesis), thereby preventing hypoglycaemia (p. 800). • The liver plays a central role in lipid metabolism, producing very low-density lipoproteins and further metabolising low- and high-density lipoproteins (see Fig. 16.14, p. 452). Dysregulation of lipid metabolism is thought to have a critical role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Lipids are now recognised to play a key part in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C, facilitating viral entry into hepatocytes. The liver produces key proteins that are involved in the coagulation cascade. Many of these coagulation factors (II, VII, IX and X) are post-translationally modified by vitamin K-dependent enzymes, and their synthesis is impaired in vitamin K deficiency (p. 997). Reduced clotting factor synthesis is an important and easily accessible biomarker of liver function in the setting of liver injury. Prothrombin time (PT; or the International Normalised Ratio, INR) is therefore one of the most important clinical tools available for the assessment of hepatocyte function. Note that the deranged PT or INR seen in liver disease may not directly equate to increased bleeding risk, as these tests do not capture the concurrent reduced synthesis of anticoagulant factors, including protein C and protein S. In general, therefore, correction of PT using blood products before minor invasive procedures should be guided by clinical risk rather than the absolute value of the PT. The liver plays a central role in the metabolism of bilirubin and is responsible for the production of bile (Fig. 23.6). Between 425 and 510 mmol (250–300 mg) of unconjugated bilirubin is produced from the catabolism of haem daily. Bilirubin in the blood is normally almost all unconjugated and, because it is not water-soluble, is bound to albumin and does not pass into the urine. Unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by hepatocytes at the sinusoidal membrane, where it is conjugated in the endoplasmic reticulum by UDP-glucuronyl transferase, producing bilirubin mono- and diglucuronide. Impaired conjugation by this enzyme is a cause of inherited hyperbilirubinaemias (see Box 23.17, p. 937). These bilirubin conjugates are water-soluble and are exported into the bile canaliculi by specific carriers on the hepatocyte membranes. The conjugated bilirubin is excreted in the bile and passes into the duodenal lumen. Once in the intestine, conjugated bilirubin is metabolised by colonic bacteria to form stercobilinogen, which may be further oxidised to stercobilin. Both stercobilinogen and stercobilin are then excreted in the stool, contributing to its brown colour. Biliary obstruction results in reduced stercobilinogen in the stool, and the stools become pale. A small amount of stercobilinogen (4 mg/day) is absorbed from the bowel, passes through the liver, and is excreted in the urine, where it is known as urobilinogen or, following further oxidisation, urobilin. The liver secretes 1–2 L of bile daily. Bile contains bile acids (formed from cholesterol), phospholipids, bilirubin and cholesterol. Several biliary transporter proteins have been identified (Fig. 23.7). Mutations in genes encoding these proteins have been identified in inherited intrahepatic biliary diseases presenting in childhood, and in adult-onset disease such as intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and gallstone formation. Approximately 9% of the normal liver is composed of immune cells (see Fig. 23.3). Cells of the innate immune system include Kupffer cells derived from blood monocytes, the liver macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, as well as ‘classical’ B and T cells of the adaptive immune response (p. 76). An additional type of atypical lymphocyte, with phenotypic features of both T cells and NK cells is thought to play an important role in host defence, through linking of innate and adaptive immunity. The enrichment of such cells in the liver reflects the unique importance of the liver in preventing microorganisms from the gut entering the systemic circulation. Investigations play an important role in the management of liver disease in three settings: • identification of the presence of liver disease • understanding disease severity (in particular, identification of cirrhosis with its complications). When planning investigations it is important to be clear as to which of these goals is being addressed. The aims of investigation in patients with suspected liver disease are shown in Box 23.1. Liver blood biochemistry (LFTs) includes the measurement of serum bilirubin, aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase and albumin. Most analytes measured by LFTs are not truly ‘function’ tests but, given that they are released by injured hepatocytes, instead provide biochemical evidence of liver cell damage. Liver function per se is best assessed by the serum albumin, PT and bilirubin because of the role played by the liver in synthesis of albumin and clotting factors and in clearance of bilirubin. Although LFT abnormalities are often non-specific, the patterns are frequently helpful in directing further investigations. Also, levels of bilirubin and albumin and the PT are related to clinical outcome in patients with severe liver disease, reflected by their use in several prognostic scores: the Child–Pugh and MELD scores in cirrhosis (see Boxes 23.30 and 23.32, p. 944), the Glasgow score in alcoholic hepatitis (see Box 23.54, p. 959) and the King’s College Hospital criteria for liver transplantation in acute liver failure (see Box 23.11, p. 934). The pattern of a modest increase in aminotransferase activity and large increases in ALP and GGT activity favours biliary obstruction and is commonly described as ‘cholestatic’ or ‘obstructive’ (Box 23.2). Isolated elevation of the serum GGT is relatively common, and may occur during ingestion of microsomal enzyme-inducing drugs, including alcohol (Box 23.3), but also in NAFLD. Other widely available biochemical tests may become altered in patients with liver disease: • Hyponatraemia occurs in severe liver disease due to increased production of antidiuretic hormone (ADH; Fig. 16.5, p. 435). • Serum urea may be reduced in hepatic failure, whereas levels of urea may be increased following gastrointestinal haemorrhage. • When high levels of urea are accompanied by raised bilirubin, high serum creatinine and low urinary sodium, this suggests hepatorenal failure, which carries a grave prognosis. • Significantly elevated ferritin suggests haemochromatosis. Modest elevations can be seen in inflammatory disease and alcohol excess. The peripheral blood count is often abnormal and can give a clue to the underlying diagnosis: • A normochromic normocytic anaemia may reflect recent gastrointestinal haemorrhage, whereas chronic blood loss is characterised by a hypochromic microcytic anaemia secondary to iron deficiency. A high erythrocyte mean cell volume (macrocytosis) is associated with alcohol misuse, but target cells in any jaundiced patient also result in a macrocytosis. Macrocytosis can persist for a long period of time after alcohol cessation, making it a poor marker of ongoing consumption. • Leucopenia may complicate portal hypertension and hypersplenism, whereas leucocytosis may occur with cholangitis, alcoholic hepatitis and hepatic abscesses. Atypical lymphocytes are seen in infectious mononucleosis, which may be complicated by an acute hepatitis. • Thrombocytopenia is common in cirrhosis and is due to reduced platelet production, and increased breakdown because of hypersplenism. Thrombopoietin, required for platelet production, is produced in the liver and levels fall with worsening liver function. Thus platelet levels are usually more depressed than white cells and haemoglobin in the presence of hypersplenism in patients with cirrhosis. A low platelet count is often an indicator of chronic liver disease, particularly in the context of hepatomegaly. Thrombocytosis is unusual in patients with liver disease but may occur in those with active gastrointestinal haemorrhage and, rarely, in hepatocellular carcinoma. A variety of tests are available to evaluate the aetiology of hepatic disease (Boxes 23.4 and 23.5). The presence of liver-related autoantibodies can be suggestive of the presence of autoimmune liver disease (although false-positive results can occur in non-autoimmune inflammatory disease such as NAFLD). Elevation in overall serum immunoglobulin levels can also be suggestive of autoimmunity (immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM). Elevated serum IgA can be seen, often in more advanced alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD, although the association is not specific. Ultrasound is non-invasive and most commonly used as a ‘first-line’ test to identify gallstones, biliary obstruction (Fig. 23.8) or thrombosis in the hepatic vasculature. Ultrasound is good for the identification of splenomegaly and abnormalities in liver texture, but is less effective at identifying diffuse parenchymal disease. Focal lesions, such as tumours, may not be detected if they are below 2 cm in diameter and have echogenic characteristics similar to normal liver tissue. Bubble-based contrast media are now routinely used and can enhance discriminant capability. Doppler ultrasound allows blood flow in the hepatic artery, portal vein and hepatic veins to be investigated. Endoscopic ultrasound provides high-resolution images of the pancreas, biliary tree and liver (see Fig. 23.45, p. 985). Computed tomography (CT) detects smaller focal lesions in the liver, especially when combined with contrast injection (Fig. 23.9). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to localise and confirm the aetiology of focal liver lesions, particularly primary and secondary tumours. Cholangiography can be undertaken by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP, Fig. 23.10), endoscopy (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, ERCP, Fig. 23.11) or the percutaneous approach (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, PTC). The latter does not allow the ampulla of Vater or pancreatic duct to be visualised. MRCP is as good as ERCP at providing images of the biliary tree but has fewer complications and is the diagnostic test of choice. Both endoscopic and percutaneous approaches allow therapeutic interventions, such as the insertion of biliary stents across malignant bile duct strictures. The percutaneous approach is only used if it is not possible to access the bile duct endoscopically. Percutaneous liver biopsy is a relatively safe procedure if the conditions detailed in Box 23.6 are met, but carries a mortality of about 0.01%. The main complications are abdominal and/or shoulder pain, bleeding and biliary peritonitis. Biliary peritonitis is rare and usually occurs when a biopsy is performed in a patient with obstruction of a large bile duct. Liver biopsies can be carried out in patients with defective haemostasis if:

Liver and biliary tract disease

Functional anatomy and physiology

Applied anatomy

Normal liver structure and blood supply

A Liver anatomy showing relationship with pancreas, bile duct and duodenum. B Hepatic lobule. C Hepatic acinus.

Liver cells

(B = B lymphocytes; NK = natural killer cells; PMN = polymorphonuclear leucocytes; T = T lymphocytes).

Stellate cell activation occurs under the influence of cytokines released by other cell types in the liver, including hepatocytes, Kupffer cells (tissue macrophages), platelets and lymphocytes. Once stellate cells become activated, they can perpetuate their own activation by synthesis of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1,) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) through autocrine loops. Activated stellate cells produce TGF-β1, stimulating the production of collagen matrix, as well as inhibitors of collagen breakdown. The inhibitors of collagen breakdown, matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 (MMP2 and MMP9), are inactivated in turn by tissue inhibitors TIMP1 and TIMP2, which are increased in fibrosis. Inflammation also contributes to fibrosis, with the cytokine profile produced by Th2 lymphocytes, such as interleukin-6 and 13 (IL-6 and IL-13). Activated stellate cells also produce endothelin 1 (ET1), which may contribute to portal hypertension. (EGF = epidermal growth factor; IGF1 = insulin-like growth factor 1; ROS = reactive oxygen species).

Biliary system and gallbladder

Hepatic function

Carbohydrate, amino acid and lipid metabolism

Clotting factors

Bilirubin metabolism and bile

On the hepatocyte basolateral membrane, NTCP (sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide) mediates uptake of conjugated bile acids from portal blood. At the canalicular membrane, these bile acids are secreted via BSEP (bile salt export pump) into bile. MDR3 (multidrug resistance protein 3), also situated on the canalicular membrane, transports phospholipid to the outer side of the membrane. This solubilises bile acids, forming micelles and protecting bile duct membranes from bile salt damage. FIC1 (familial intrahepatic cholestasis 1) moves phosphatidylserine from the inside to the outside of the canalicular membrane; mutations result in familial cholestasis syndrome in childhood. MDR2 (multidrug resistance 2) regulates transport of glutathione. MRP2 (multidrug resistance protein 2) transports bilirubin and is induced by rifampicin. OATP (organic anion transporter protein) transports bilirubin and organic anions.

Immune regulation

Investigation of liver and hepatobiliary disease

Liver blood biochemistry

Alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase

Other biochemical tests

Haematological tests

Blood count

Immunological tests

Imaging

Ultrasound

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

The liver is small and has an irregular outline (black arrow), the spleen is enlarged (long white arrow), fluid (ascites) is seen around the liver, and collateral vessels are present around the proximal stomach (short white arrow).

Cholangiography

The proximal common bile duct (B) is dilated but the pancreatic duct (P) is normal.

Histological examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Liver and biliary tract disease