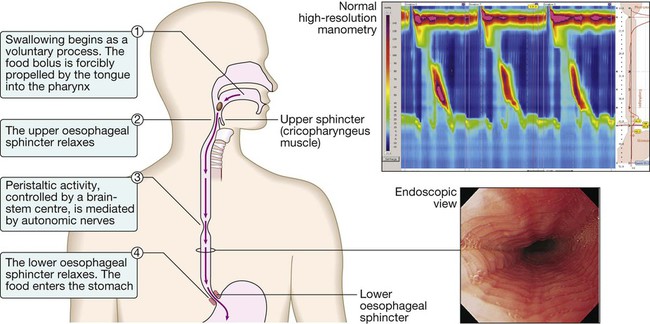

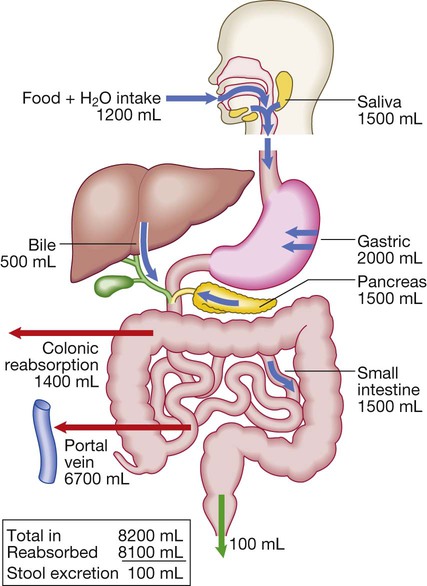

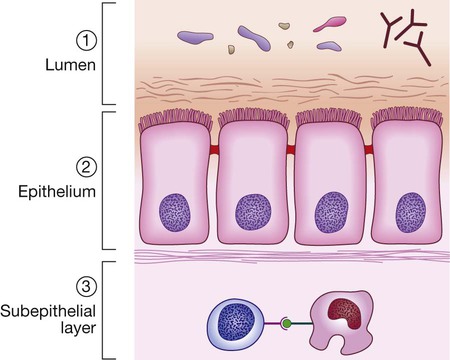

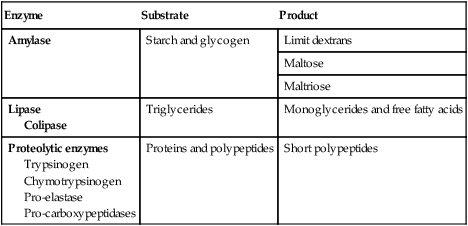

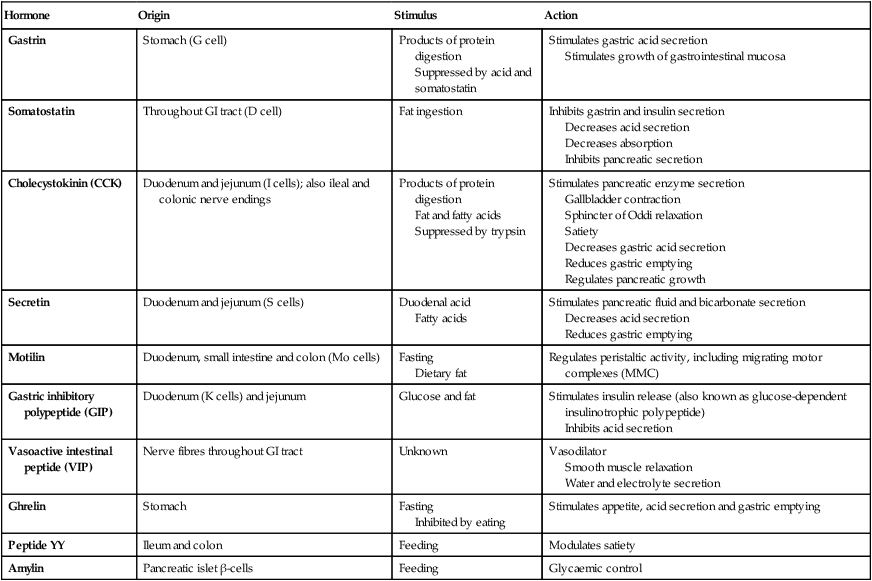

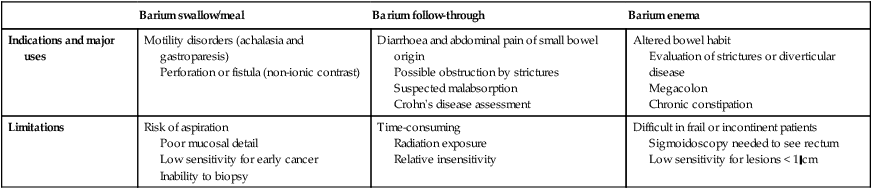

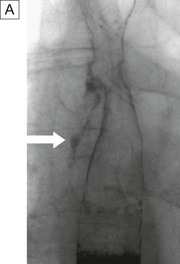

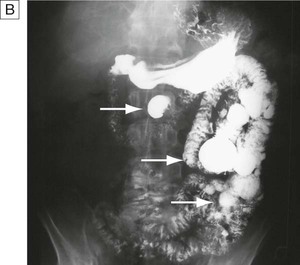

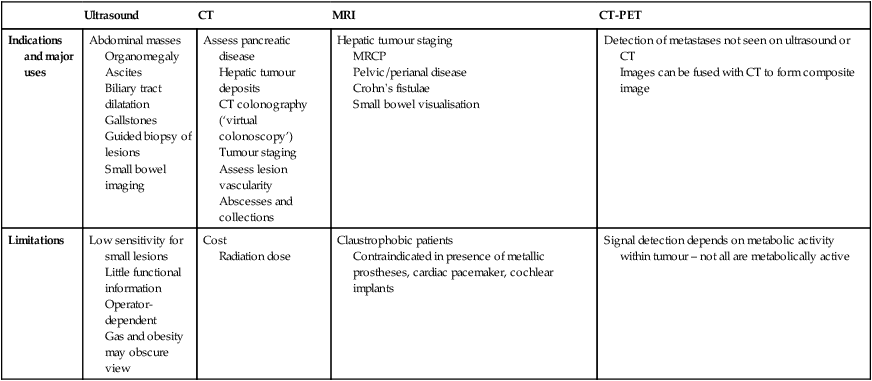

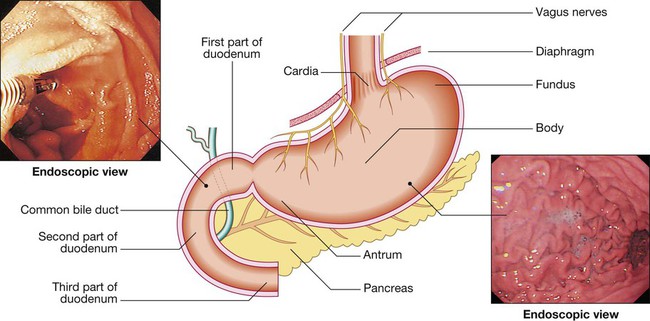

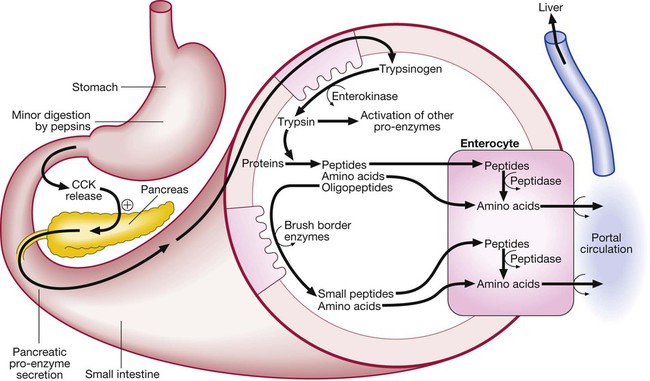

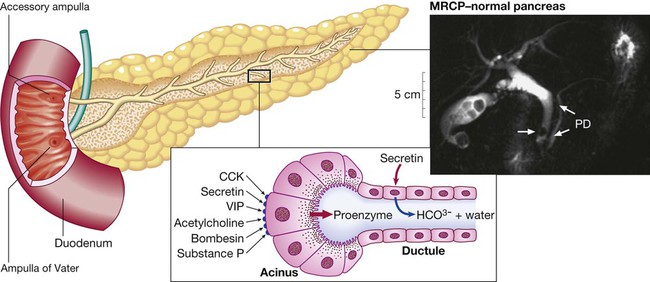

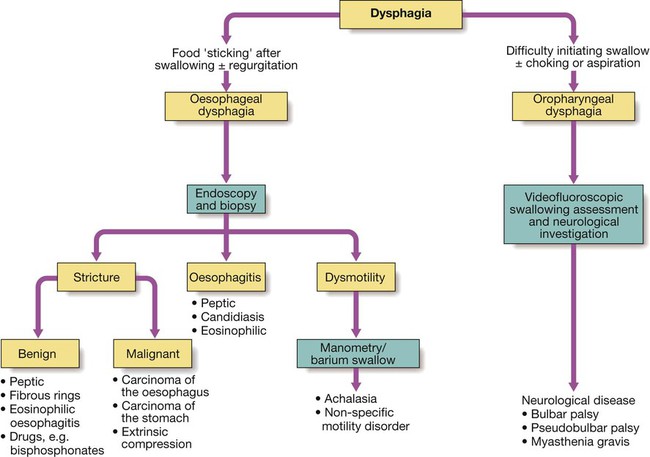

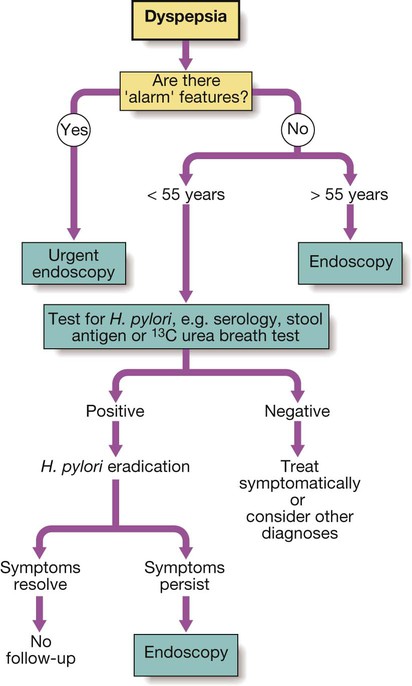

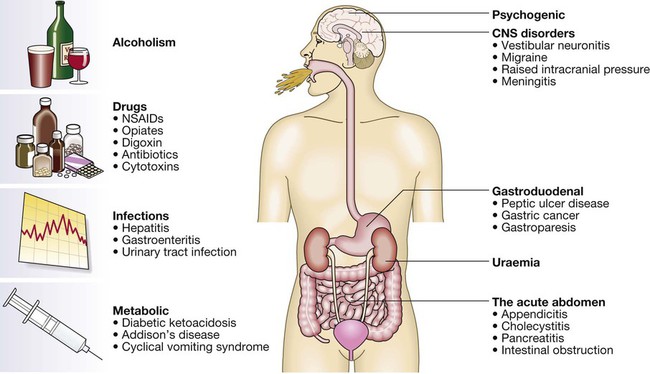

Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Approximately 10% of all general practitioner consultations in the United Kingdom are for indigestion, and 1 in 14 is for diarrhoea. Infective diarrhoea and malabsorption are responsible for much ill health and many deaths in the developing world. The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site for cancer development. Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer in men, and population-based screening programmes exist in many countries. Functional bowel disorders affect up to 10–15% of the population and consume considerable health-care resources. The inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, together affect 1 in 250 people in the Western world, with substantial associated morbidity. This muscular tube extends 25 cm from the cricoid cartilage to the cardiac orifice of the stomach. It has an upper and a lower sphincter. A peristaltic swallowing wave propels the food bolus into the stomach (Fig. 22.1). The stomach acts as a ‘hopper’, retaining and grinding food, then actively propelling it into the upper small bowel (Fig. 22.2). Gastrin, histamine and acetylcholine are the key stimulants of acid secretion. Hydrogen and chloride ions are secreted from the apical membrane of gastric parietal cells into the lumen of the stomach by a hydrogen–potassium adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) (‘proton pump’) (Fig. 22.3). The hydrochloric acid sterilises the upper gastrointestinal tract and converts pepsinogen – which is secreted by chief cells – to pepsin. The glycoprotein intrinsic factor, secreted in parallel with acid, is necessary for vitamin B12 absorption. The small bowel extends from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocaecal valve (Fig. 22.4). During fasting, a wave of peristaltic activity passes down the small bowel every 1–2 hours. Entry of food into the gastrointestinal tract stimulates small bowel peristaltic activity. Functions of the small intestine are: • digestion (mechanical, enzymatic and peristaltic) • absorption – the products of digestion, water, electrolytes and vitamins • protection against ingested toxins Dietary lipids comprise long-chain triglycerides, cholesterol esters and lecithin. Lipids are insoluble in water and undergo lipolysis and incorporation into mixed micelles before they can be absorbed into enterocytes along with the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, K and E. The lipids are processed within enterocytes and pass via lymphatics into the systemic circulation. Fat absorption and digestion can be considered as a stepwise process, as outlined in Figure 22.5. The steps involved in protein digestion are shown in Figure 22.6. Intragastric digestion by pepsin is quantitatively modest but important because the resulting polypeptides and amino acids stimulate CCK release from the mucosa of the proximal jejunum, which in turn stimulates release of pancreatic proteases, including trypsinogen, chymotrypsinogen, pro-elastases and procarboxypeptidases, from the pancreas. On exposure to brush border enterokinase, inert trypsinogen is converted to the active proteolytic enzyme trypsin, which activates the other pancreatic proenzymes. Trypsin digests proteins to produce oligopeptides, peptides and amino acids. Oligopeptides are further hydrolysed by brush border enzymes to yield dipeptides, tripeptides and amino acids. These small peptides and the amino acids are actively transported into the enterocytes, where intracellular peptidases further digest peptides to amino acids. Amino acids are then actively transported across the basal cell membrane of the enterocyte into the portal circulation and the liver. • the paracellular route, in which passive flow through tight junctions between cells is a consequence of osmotic, electrical or hydrostatic gradients • the transcellular route across apical and basolateral membranes by energy-requiring specific active transport carriers (pumps). In healthy individuals, fluid balance is tightly controlled, such that only 100 mL of the 8 litres of fluid entering the gastrointestinal tract daily is excreted in stools (Fig. 22.7). There are several levels of defence in the small bowel (Fig. 22.8). Firstly, the gut lumen contains host bacteria, mucins and secreted antibacterial products, including defensins and immunoglobulins which help combat pathogenic infections. Secondly, epithelial cells have relatively impermeable brush border membranes, and passage between cells is prevented by tight and adherens junctions. These cells can react to foreign peptides (‘innate immunity’) using pattern recognition receptors found on cell surfaces (Toll receptors) or intracellularly. Lastly, in the subepithelial layer, immune responses occur under control of the adaptive immune system in response to pathogenic compounds. The exocrine pancreas (Box 22.1) is necessary for the digestion of fat, protein and carbohydrate. Proenzymes are secreted from pancreatic acinar cells in response to circulating gastrointestinal hormones (Fig. 22.9) and are activated by trypsin. Bicarbonate-rich fluid is secreted from ductular cells to produce an optimum alkaline pH for enzyme activity. The colon (Fig. 22.10) absorbs water and electrolytes. It also acts as a storage organ and has contractile activity. Two types of contraction occur. The first of these is segmentation (ring contraction), which leads to mixing but not propulsion; this promotes absorption of water and electrolytes. Propulsive (peristaltic contraction) waves occur several times a day and propel faeces to the rectum. All activity is stimulated after meals, probably in response to release of motilin and CCK. Faecal continence depends upon maintenance of the anorectal angle and tonic contraction of the external anal sphincters. On defecation, there is relaxation of the anorectal muscles, increased intra-abdominal pressure from the Valsalva manœuvre and contraction of abdominal muscles, and relaxation of the anal sphincters. • parasympathetic pathways (vagal and sacral efferent), which are cholinergic, and increase smooth muscle tone and promote sphincter relaxation • sympathetic pathways, which release noradrenaline (norepinephrine), reduce smooth muscle tone and stimulate sphincter contraction. X-rays with contrast medium are usually performed to assess not only anatomical abnormalities but also motility. Barium sulphate provides good mucosal coating and excellent opacification but can precipitate impaction proximal to an obstructive lesion. Water-soluble contrast is used to opacify bowel prior to abdominal computed tomography and in cases of suspected perforation. The double contrast technique improves mucosal visualisation by using gas to distend the barium-coated intestinal surface. Contrast studies are useful for detecting filling defects, such as tumours, strictures, ulcers and motility disorders, but are inferior to endoscopic procedures and more sophisticated cross-sectional imaging techniques, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. The major uses and limitations of various contrast studies are shown in Box 22.3 and Figure 22.11. Ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are key tests in the evaluation of intra-abdominal disease. They are non-invasive and offer detailed images of the abdominal contents. Their main applications are summarised in Box 22.4 and Figure 22.12. Videoendoscopes provide high-definition imaging and accessories can be passed down the endoscope to allow both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, some of which are illustrated in Figure 22.13. Endoscopes with magnifying lenses allow almost microscopic detail to be observed, and imaging modalities, such as confocal endomicroscopy, autofluorescence and ‘narrow band imaging’, are increasingly used to detect subtle abnormalities not visible by standard ‘white light’ endoscopy. This is performed under light intravenous benzodiazepine sedation, or using only local anaesthetic throat spray after the patient has fasted for at least 4 hours. With the patient in the left lateral position, the entire oesophagus (excluding pharynx), stomach and first two parts of duodenum can be seen. Indications, contraindications and complications are given in Box 22.5. Capsule endoscopy (Fig. 22.14) uses a capsule containing an imaging device, battery, transmitter and antenna; as it traverses the small intestine, it transmits images to a battery-powered recorder worn on a belt round the patient’s waist. After approximately 8 hours, the capsule is excreted. Images from the capsule are analysed as a video sequence and it is usually possible to localise the segment of small bowel in which lesions are seen. Abnormalities detected usually require enteroscopy for confirmation and therapy. Indications, contraindications and complications are listed in Box 22.6. While endoscopy can reach the proximal small intestine in most patients, a newer technique called double balloon enteroscopy is also available, which uses a long endoscope with a flexible overtube. Sequential and repeated inflation and deflation of balloons on the tip of the overtube and enteroscope allow the operator to push and pull along the entire length of the small intestine to the terminal ileum, in order to diagnose or treat small bowel lesions detected by capsule endoscopy or other imaging modalities. Indications, contraindications and complications are listed in Box 22.7. Sigmoidoscopy can be carried out either in the outpatient clinic using a 20 cm rigid plastic sigmoidoscope or in the endoscopy suite using a 60 cm flexible colonoscope following bowel preparation. When sigmoidoscopy is combined with proctoscopy, accurate detection of haemorrhoids, ulcerative colitis and distal colorectal neoplasia is possible. After full bowel cleansing, it is possible to examine the entire colon and the terminal ileum using a longer colonoscope. Indications, contraindications and complications of colonoscopy are listed in Box 22.8. Using a side-viewing duodenoscope, it is possible to cannulate the main pancreatic duct and common bile duct. Nowadays, ERCP is mainly used in the treatment of a range of biliary and pancreatic diseases that have been identified by other imaging techniques such as MRCP, EUS and CT. Indications for and risks of ERCP are listed in Box 22.9. A number of dynamic tests can be used to investigate aspects of gut function, including digestion, absorption, inflammation and epithelial permeability. Some of the more commonly used ones are listed in Box 22.12. In the assessment of suspected malabsorption, blood tests (full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), folate, vitamin B12, iron status, albumin, calcium and phosphate) are essential, and endoscopy is undertaken to obtain mucosal biopsies. Faecal calprotectin is very sensitive at detecting mucosal inflammation. A barium swallow can give useful information about oesophageal motility. Videofluoroscopy, with joint assessment by a speech and language therapist and a radiologist, may be necessary in difficult cases. Oesophageal manometry (see Fig. 22.1, p. 840), often in conjunction with 24-hour pH measurements, is of value in diagnosing cases of refractory gastro-oesophageal reflux, achalasia and non-cardiac chest pain. Oesophageal impedance testing is useful for detecting non-acid or gas reflux events, especially in patients with atypical symptoms or those who respond poorly to acid suppression. This involves administering a test meal containing solids and liquids labelled with different radioisotopes and measuring the amount retained in the stomach afterwards (Box 22.13). It is useful in the investigation of suspected delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis) when other studies are normal. Many different radioisotope tests are used (see Box 22.13). In some, structural information is obtained, such as the localisation of a Meckel’s diverticulum. Others provide functional information, such as the rate of gastric emptying or ability to reabsorb bile acids. Yet others are tests of infection and rely on the presence of bacteria to hydrolyse a radio-labelled test substance followed by detection of the radioisotope in expired air, such as the urea breath test for H. pylori. Dysphagia can occur due to problems in the oropharynx or oesophagus (Fig. 22.15). Oropharyngeal disorders affect the initiation of swallowing at the pharynx and upper oesophageal sphincter. The patient has difficulty initiating swallowing and complains of choking, nasal regurgitation or tracheal aspiration. Drooling, dysarthria, hoarseness and cranial nerve or other neurological signs may be present. Oesophageal disorders cause dysphagia by obstructing the lumen or by affecting motility. Patients with oesophageal disease complain of food ‘sticking’ after swallowing, although the level at which this is felt correlates poorly with the true site of obstruction. Swallowing of liquids is normal until strictures become extreme. Dysphagia should always be investigated urgently. Endoscopy is the investigation of choice because it allows biopsy and dilatation of strictures. If no abnormality is found, then barium swallow with videofluoroscopic swallowing assessment is indicated to detect major motility disorders. In some cases, oesophageal manometry is required. High-resolution manometry allows accurate classification of abnormalities. Figure 22.15 summarises a diagnostic approach to dysphagia and lists the major causes. Dyspepsia describes symptoms such as discomfort, bloating and nausea, which are thought to originate from the upper gastrointestinal tract. There are many causes (Box 22.14), including some arising outside the digestive system. Heartburn and other ‘reflux’ symptoms are separate entities and are considered elsewhere. Although symptoms often correlate poorly with the underlying diagnosis, a careful history is important to detect ‘alarm’ features requiring urgent investigation (Box 22.15) and to detect atypical symptoms which might be due to problems outside the gastrointestinal tract. Dyspepsia affects up to 80% of the population at some time in life and most patients have no serious underlying disease. Patients who present with new dyspepsia at an age of more than 55 years and younger patients unresponsive to empirical treatment require investigation to exclude serious disease. An algorithm for the investigation of dyspepsia is outlined in Figure 22.16. Vomiting is a complex reflex involving both autonomic and somatic neural pathways. Synchronous contraction of the diaphragm, intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles raises intra-abdominal pressure and, combined with relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter, results in forcible ejection of gastric contents. It is important to distinguish true vomiting from regurgitation and to elicit whether the vomiting is acute or chronic (recurrent), as the underlying causes may differ. The major causes are shown in Figure 22.17.

Alimentary tract and pancreatic disease

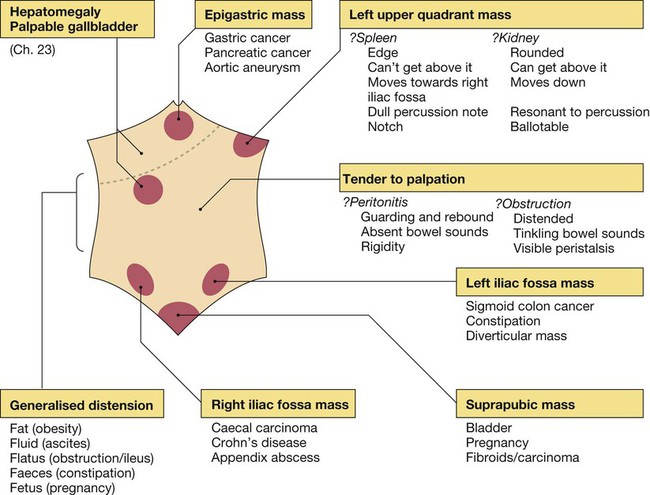

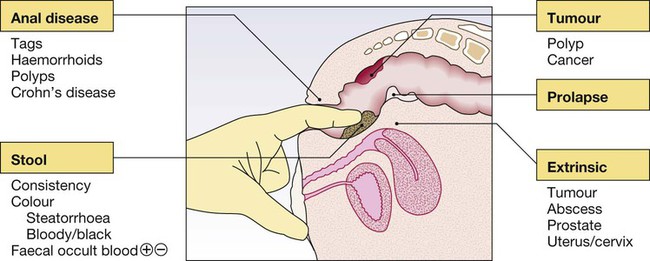

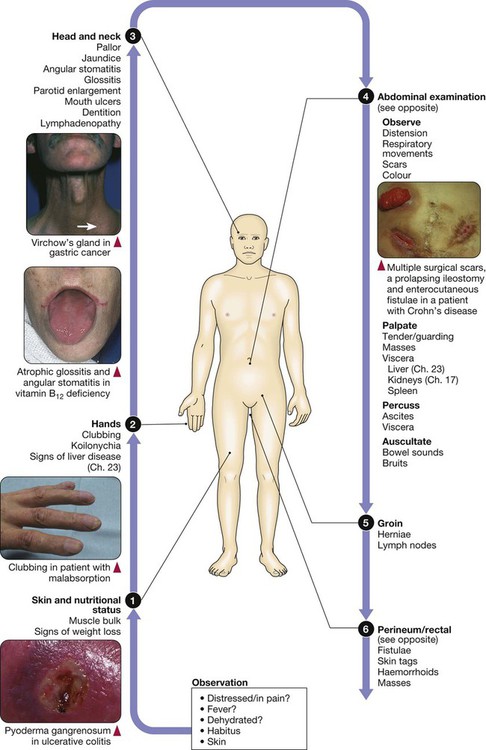

Clinical examination of the gastrointestinal tract

Functional anatomy and physiology

Oesophagus, stomach and duodenum

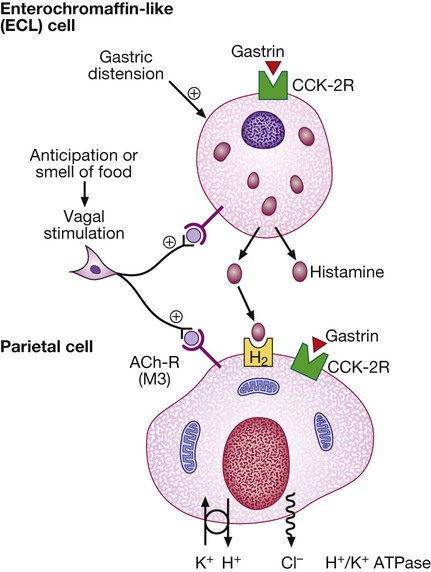

Gastric secretion

Gastrin released from antral G cells in response to food (protein) binds to cholecystokinin receptors (CCK-2R) on the surface of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, which in turn release histamine. The histamine binds to H2 receptors on parietal cells and this leads to secretion of hydrogen ions, in exchange for potassium ions at the apical membrane. Parietal cells also express CCK-2R and it is thought that activation of these receptors by gastrin is involved in regulatory proliferation of parietal cells. Cholinergic (vagal) activity and gastric distension also stimulate acid secretion; somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) may inhibit it. (ACh-R = acetylcholine receptor; ATPase = adenosine triphosphatase)

Small intestine

Epithelial cells are formed in crypts and differentiate as they migrate to the tip of the villi to form enterocytes (absorptive cells) and goblet cells.

Digestion and absorption

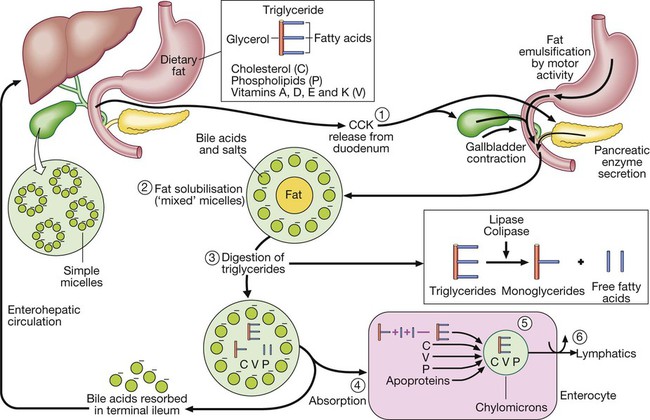

Fat

Step 1: Luminal phase. Fatty acids stimulate cholecystokinin (CCK) release from the duodenum and upper jejunum. The CCK stimulates release of amylase, lipase, colipase and proteases from the pancreas, causes gallbladder contraction and relaxes the sphincter of Oddi, leading bile to flow into the intestine. Step 2: Fat solubilisation. Bile acids and salts combine with dietary fat to form mixed micelles, which also contain cholesterol and fat-soluble vitamins. Step 3: Digestion. Pancreatic lipase, in the presence of its co-factor, colipase, cleaves long-chain triglycerides, yielding fatty acids and monoglycerides. Step 4: Absorption. Mixed micelles diffuse to the brush border of the enterocytes. Within the brush border, long-chain fatty acids bind to proteins, which transport the fatty acids into the cell, whereas cholesterol, short-chain fatty acids, phospholipids and fat-soluble vitamins enter the cell directly. The bile salts remain in the small intestinal lumen and are actively transported from the terminal ileum into the portal circulation and returned to the liver (the enterohepatic circulation). Step 5: Re-esterification. Within the enterocyte, fatty acids are re-esterified to form triglycerides. Triglycerides combine with cholesterol ester, fat-soluble vitamins, phospholipids and apoproteins to form chylomicrons. Step 6: Transport. Chylomicrons leave the enterocytes by exocytosis, enter mesenteric lymphatics, pass into the thoracic duct, and eventually reach the systemic circulation.

Protein

Water and electrolytes

Protective function of the small intestine

Physical defence mechanisms

Pancreas

Ductular cells secrete alkaline fluid in response to secretin. Acinar cells secrete digestive enzymes from zymogen granules in response to a range of secretagogues. The photograph shows a normal pancreatic duct (PD) and side branches, as defined at magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Note the incidental calculi in the gallbladder and common bile duct (arrow). (CCK = cholecystokinin; VIP = vasoactive intestinal polypeptide)

Colon

Control of gastrointestinal function

The nervous system and gastrointestinal function

Investigation of gastrointestinal disease

Imaging

Contrast studies

Ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

Endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

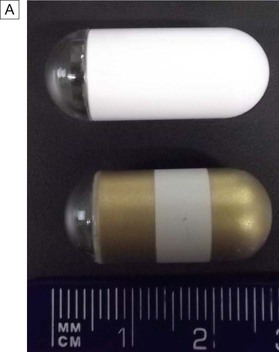

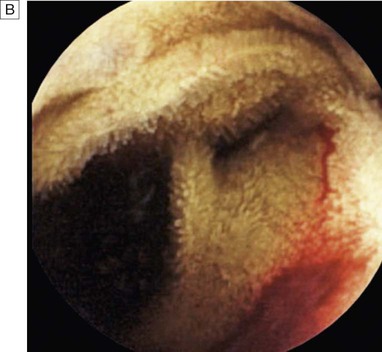

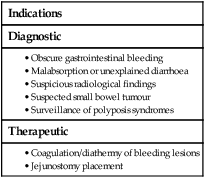

Capsule endoscopy

Double balloon enteroscopy

Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

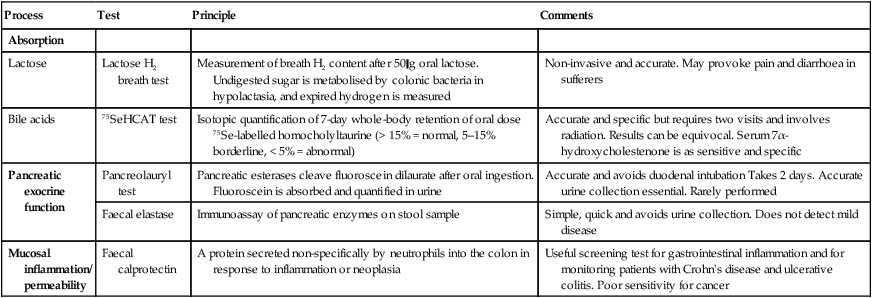

Tests of function

Oesophageal motility

Gastric emptying

Radioisotope tests

Presenting problems in gastrointestinal disease

Dysphagia

Investigations

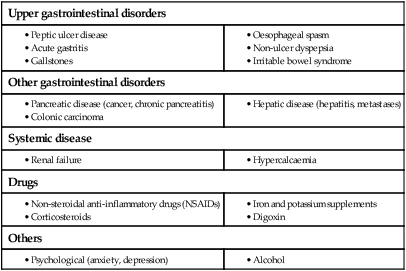

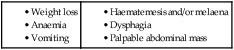

Dyspepsia

Vomiting

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Alimentary tract and pancreatic disease