Chapter 7 Upper Limb

Chapter 7 Upper Limb

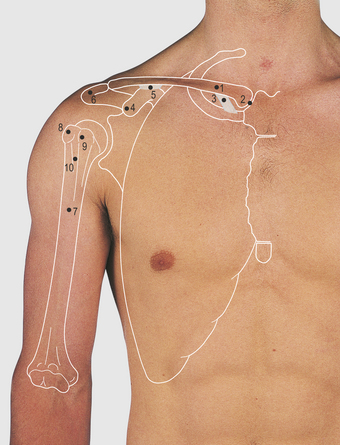

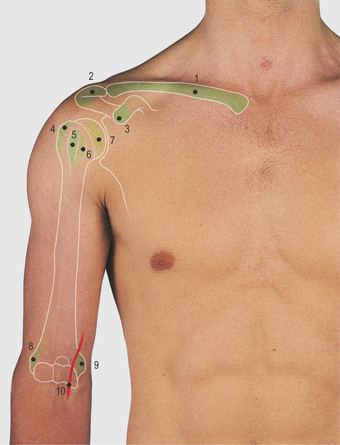

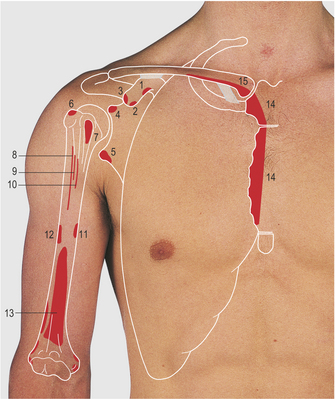

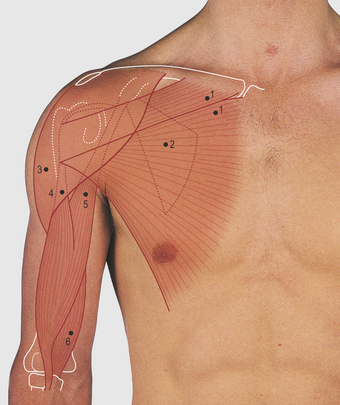

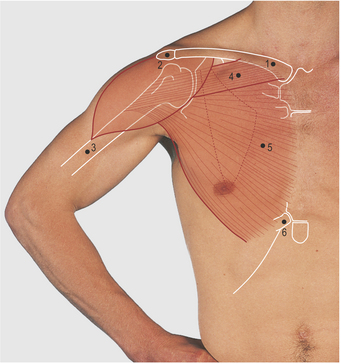

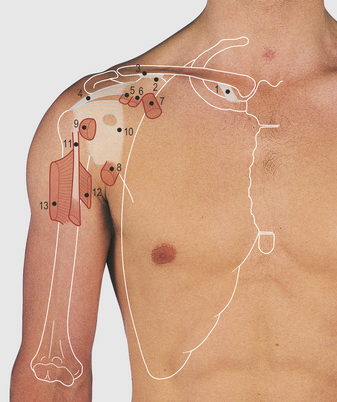

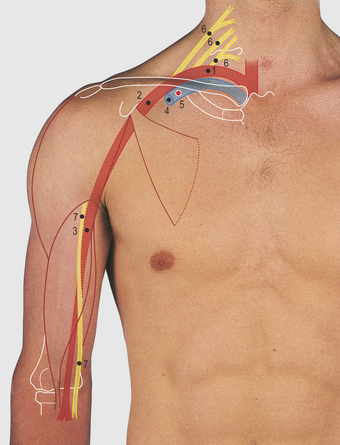

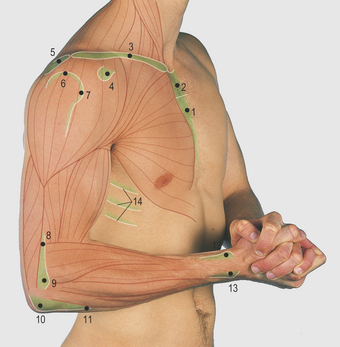

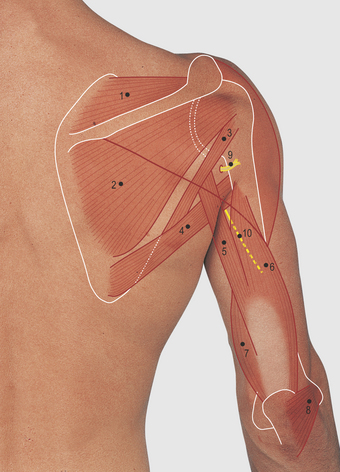

Anterior aspect of the shoulder and upper arm (Figs 7.1–7.12)

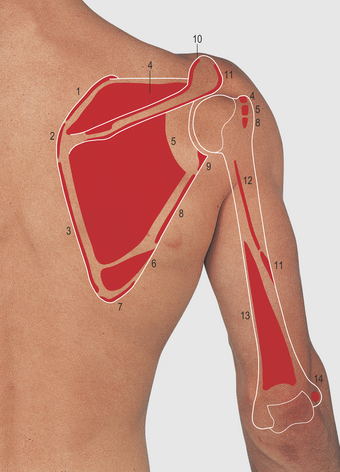

The shoulder girdle is the means by which the humerus of the upper limb is attached to the axial skeleton. It consists of the scapula and the clavicle (Fig. 7.2) and is supported by powerful proximal muscles.

The lateral third of the clavicle, the acromion and the spine give lateral attachment to the trapezius muscle (Fig. 7.16, p. 70), which raises, laterally rotates and draws the scapula medially. It is supplied by the accessory (11th cranial) nerve. The deltoid muscle takes its medial attachments from the lateral quarter of the clavicle, the acromion and the spine of the scapula, and forms the smooth contour of the shoulder. Laterally, it is attached to the deltoid tubercle on the lateral aspect of the humerus. It is the prime abductor of the arm, its anterior fibres contributing to flexion and the posterior fibres to extension of the limb; it is supplied by the axillary nerve. The upper end of the humerus can be palpated through the fibres of the relaxed deltoid.

The pectoralis major muscle has two medial heads (Fig. 7.6). The clavicular is attached to the medial two-thirds of the clavicle and the sternocostal to the anterior surface of the sternum, the upper five to seven costal cartilages and the upper part of the external oblique aponeurosis. Laterally, the two heads converge onto a narrow tendon which passes deep to the deltoid muscle to be attached to the lateral lip of the bicipital groove on the humerus. The superior head overlaps the inferior and together they form the bulk of the anterior axillary fold (Fig. 4.14, p. 38). The muscle as a whole is a powerful abductor and medial rotator of the arm; the clavicular head, with the anterior fibres of deltoid, flexes the arm. In contrast, the sternocostal head is a powerful extensor from the flexed position, acting with latissimus dorsi (Fig. 7.16, p. 70), e.g. pulling the body up on an overhead bar and the follow-through of a tennis serve. It can be demonstrated clinically by pressing hands on hips (Fig. 7.7). The muscle is supplied by the medial and the lateral pectoral nerves from the brachial plexus.

The axillary artery and vein can be exposed through an incision through skin and superficial fascia, separating the two heads of the pectoralis major muscle and dividing the clavipectoral fascia. The axillary vein becomes the subclavian vein at the outer border of the first rib behind the middle of the clavicle and is closely related to the posterior surface of this bone. A needle inserted below the clavicle and aimed superomedially adjacent to the posterior aspect of the bone will enter the vein; this provides an important point of access (Fig. 7.9).

Actions of the biceps muscle

The biceps muscle forms a prominence on the anterior aspect of the arm. Its short head is attached to the coracoid process and the long head passes between the greater and lesser humeral tuberosities, within the bicipital groove, and is attached to the superior aspect of the glenoid fossa on the scapula. Inferiorly the muscle is attached to the bicipital tuberosity on the radius; it has no attachments to the humerus. The muscle flexes the elbow and is a powerful supinator of the forearm: combining these actions produces the greatest prominence of the muscle belly (Fig. 7.11C). The muscle is supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve, which also supplies the coracobrachialis and brachialis muscles. The former muscle is not easily palpable in the lateral aspect of the axilla but the latter forms, with the biceps, the muscle bulk of the anterior aspect of the upper arm.

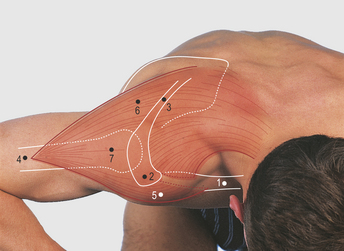

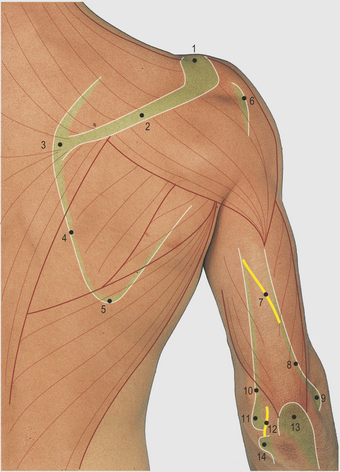

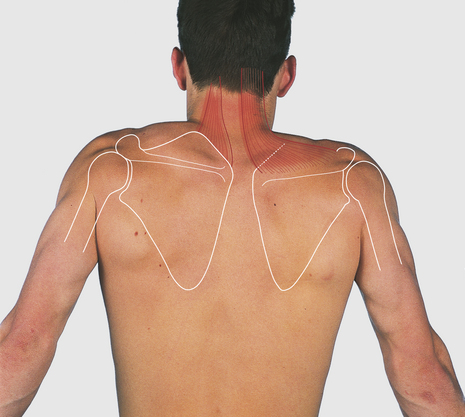

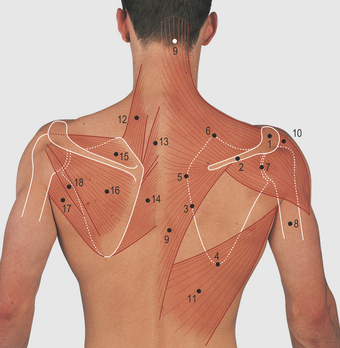

Posterior aspect of the shoulder and upper arm (Figs 7.13–7.20)

The acromion and spine of the scapula are subcutaneous. The deltoid muscle forms the smooth prominence of the shoulder overlapping the upper end of the humerus; its posterior fibres aid in extension of the shoulder (Fig. 7.16).

7.16 Posterior aspect of the shoulder and upper arm: bones and muscles of the shoulder girdle

Right, superficial muscles; left, deep muscles

The trapezius forms a wide triangular muscle sheet with its base medially attached to the medial half of the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone, the ligamentum nuchae and the spines and interspinous ligaments of the lower cervical and all the thoracic vertebrae. Laterally the muscle is attached to the lateral third of the clavicle and to the length of the acromion and the spine of the scapula. The wide medial attachment of the muscle produces a wide range of scapular movements, raising, laterally rotating and drawing the bone medially (Fig. 7.16 and 7.18–7.20). The muscle is supplied by the accessory (11th cranial) nerve.

The muscle bulk of the posterior aspect of the upper arm is produced by the triceps muscle with a smaller contribution from the anconeus near the elbow (Fig. 7.14). The triceps is attached to the posterior shaft of the humerus above (lateral head) and below (medial head) the radial groove and, by its long head, below the glenoid fossa on the scapula. The muscle is attached distally to the palpable olecranon process of the ulna and is a powerful extensor of the elbow; it is supplied by the radial nerve.

Movements of the scapula and shoulder joint

Movements of the upper limb away from the trunk involve movements both of the scapula and of the shoulder joint. This can be confirmed by watching a subject from behind and then trying to hold the scapula still during shoulder movements (Figs 7.18–7.20). Powerful muscles raise, lower, draw medially and laterally, and rotate the bone medially (medial movement of the inferior angle and downward facing of the glenoid fossa) and laterally. During these movements there is also some compensatory movement in the joints at either end of the clavicle.

Flexion of the shoulder joint is by the clavicular head of the pectoralis major, the anterior fibres of the deltoid and coracobrachialis muscles. Extension is by the posterior fibres of deltoid and, from the flexed position, by the sternocostal head of pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi muscles. Abduction is initiated by the supraspinatus and continued by the deltoid muscles. Medial rotation is by pectoralis major, the anterior fibres of deltoid and latissimus dorsi, teres major and subscapularis muscles. Lateral rotation is by the posterior fibres of deltoid, teres minor and the infraspinatus muscles.

Cubital fossa (Figs 7.21–7.26)

The cubital fossa is bounded superiorly by a line through the palpable medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus, laterally by the brachioradialis muscle and medially by the pronator teres muscle (Figs 7.22 and 7.25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree