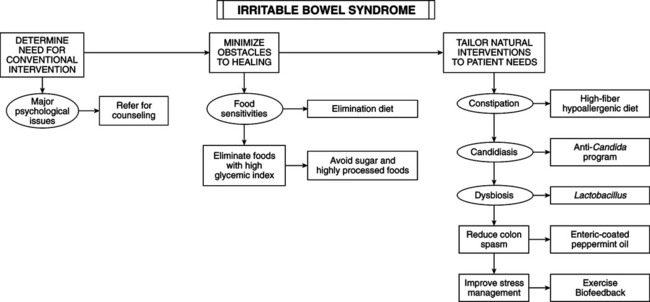

• Functional disorder of the large intestine with no evidence of accompanying structural defect. • Characterized by some combination of: — Altered bowel function, constipation, or diarrhea — Hypersecretion of colonic mucus — Dyspeptic symptoms (flatulence, nausea, anorexia) • Synonyms include nervous indigestion, spastic colitis, mucous colitis, intestinal neurosis • Splenic flexure syndrome is a variant of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in which gas in bowel leads to pain in lower chest or left shoulder. • Many patients with IBS also have extraintestinal symptoms: sexual dysfunction, fibromyalgia, dyspareunia, urinary frequency and urgency, poor sleep, menstrual difficulties, lower back pain, headache, chronic fatigue, and insomnia—which increase in number with severity of IBS. IBS is the most common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder in general practice, accounting for 30%-50% of all referrals to gastroenterologists. Many sufferers never seek medical attention. Fifteen percent of the population have IBS symptoms; women predominate 2:1 (men do not report symptoms as often). Etiology is attributed to physiologic, psychological, and dietary factors. IBS often is a diagnosis of exclusion, but clinical judgment is needed to determine extent of diagnostic process. Detailed history and physical examination can eliminate vagueness in diagnosing IBS. Distension, relief of pain with bowel movements, and onset of loose or more frequent bowel movements with pain correlate best with diagnosis of IBS. Comprehensive stool and digestive analysis (Textbook, “Comprehensive Digestive Stool Analysis 2.0”), complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid stimulating hormone, and serum protein concentration are necessary to determine diagnosis. If diarrhea is the predominant symptom, consider antiendomysial antibody test to rule out celiac disease (see the chapter on celiac disease). If no discernible cause is identified, screening for fecal occult blood and flexible sigmoidoscopy are indicated in patients <50 years and colonoscopy in patients >50 years old. • Dietary fiber: patients with constipation are more likely to respond to dietary fiber than are those with diarrhea. Food allergy has been ignored in studies of fiber. Wheat bran is usually contraindicated because food allergy is a significant factor in IBS. Fiber from fruit and vegetables, rather than cereals, is more beneficial in some patients. In certain cases, especially diarrhea cases, fiber may aggravate diarrhea. Cooked vegetables in small quantities at first may be most helpful (Textbook, “Role of Dietary Fiber in Health and Disease”). Partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG), from the ancient guar plant Cyamopsis tetragonolobus of India and Pakistan, is a natural, water-soluble fiber that decreases frequency of IBS symptoms—flatulence, abdominal spasms, and tension. At a dosage of 5 g q.d. PHGG works well for altered intestinal motility and is easy to use because of its nongelling properties, unlike unhydrolyzed gum. • Food allergy: the type of food sensitivity most significant in IBS is nonimmunologic—food intolerance rather than food allergy (Textbook, “Food Allergy”). Two thirds of patients with IBS have food intolerances. Foods rich in carbohydrates and fats, coffee, alcohol, and hot spices are problematic. The most common allergens are dairy (40%-44%) and grains (40%-60%). The reaction arises from prostaglandin synthesis or immunoglobulin (Ig) G rather than IgE mediation; thus skin tests and IgE radioallergosorbent test are poor indicators of intolerances. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ACT or ELISA IgE/IgG4 may be better indicators. Many sensitivities are undetectable by current lab procedures. Elimination diets can give marked clinical improvement. Many patients with IBX have associated symptoms of vasomotor instability (palpitation, hyperventilation, fatigue, excessive sweating, headache) consistent with food allergy or intolerance reactions. • Sugar: meals high in refined sugar contribute to IBS and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth by decreasing intestinal motility. A rapid rise in blood sugar slows GI tract peristalsis. Glucose is primarily absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum; hence the message affects this portion of GI tract the strongest; the duodenum and jejunum become atonic.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

DIAGNOSTIC SUMMARY

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine