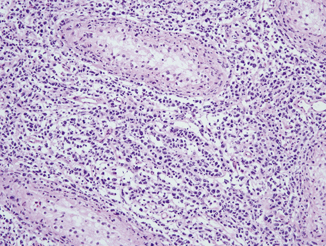

Fig. 41.1

Frozen section of an adenomatoid tumor with cords of tumor cells and fibrotic background mimicking an adenocarcinoma. Original magnification × 100

“Benign” tumors: Most of small masses often detected incidentally (e.g., scrotal ultrasonography) are benign. In the management of these tumors, radical orchiectomy may not be necessary. Neoplasms generally with a benign course suitable for testicular-sparing surgery include Leydig cell tumor (Fig. 41.2), Sertoli cell tumor (Fig. 41.3), epidermoid cyst/dermoid cyst, and teratoma in prepubertal patients. In our experience, there have been situations where an equivocal or incorrect frozen section diagnoses, such as “suspicious for epidermoid cyst” and “mature teratoma” for epidermoid cysts (on permanent section), resulted in radical orchiectomy [5]. Therefore, clear and effective communication between the surgeon and pathologist is always essential.

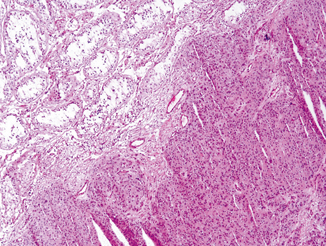

Fig. 41.2

Frozen section of a Leydig cell tumor showing well-circumscribed tumor composed of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large round nuclei, and frequent small nucleoli. Original magnification × 40

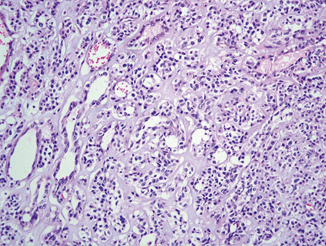

Fig. 41.3

Frozen section of a Sertoli cell tumor showing nests and tubules lined by uniform cells with clear and vacuolated cytoplasm and paucicellular stroma. Original magnification × 100

Malignant germ cell tumors: It is very unusual to consider partial orchiectomy for the treatment of malignant germ cell tumors . Patients with palpable masses and hormone-related manifestation such as elevated serum markers and gynecomastia are not typically candidates for testicular-sparing surgery. However, it may be an option in some highly selected patients who have a small mass (less than 2 cm in size) in a solitary testicle or bilateral concurrent testicular tumors and a desire for fertility or avoidance of androgen supplementation [1, 2]. When a partial orchiectomy specimen is submitted for intraoperative consultation, it is important to include adjacent normal-appearing testicular parenchyma in FSA in order to detect potentially multifocal intratubular germ cell neoplasia. Other reported pitfalls of FSA of germ cell tumors include distinctions between squamous metaplasia in a hydrocele or epididymal lesions vs. teratoma, granulomatous process vs. seminoma (Fig. 41.4), and mixed germ cell tumor (when sampled focally) vs. pure seminoma [6].

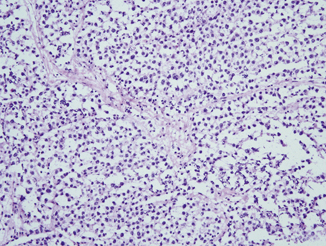

Fig. 41.4

Frozen section of a classic seminoma showing monotonous, evenly spaced tumor cells with abundant clear cytoplasm. Noticed is also the presence of fibrovascular septae filled with lymphocytic infiltrate. Original magnification × 100

Lymphoma: Lymphoma is the most common testicular malignancy in elderly men and frequently involves both testicles. Most of primary testicular lymphomas display a B-cell immunophenotype (e.g., large B-cell lymphoma) (Fig. 41.5). However, T-cell or follicular lymphomas involving the testis have also been reported [7, 8]. Systemic chemotherapy remains the standard treatment for testicular lymphomas, but the blood–testis barrier is known to impede the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to the testis. Thus, radical orchiectomy is beneficial in providing tissue for diagnosis and removing a potential sanctuary site for tumor cells. Accordingly, frozen section diagnosis of lymphoma/lymphoid proliferation in a biopsy specimen does not readily abstain from proceeding with radical orchiectomy, while it is helpful in reserving fresh tumor from the orchiectomy specimen for flow cytometry and molecular genetics analyses.