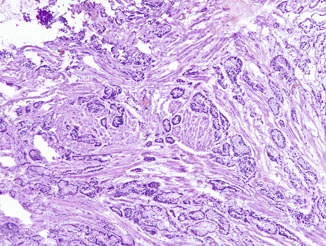

Fig. 10.1

Benign glands “infiltrating” skeletal muscle at the apex. Original magnification × 100

Bladder neck: The specimen submitted for FSA is usually larger than biopsies from other locations, often in excess of 1 cm. It should be sectioned, if necessary, and submitted entirely for FSA. These biopsies usually consist of more prominent smooth muscle fibers, occasionally with benign prostatic epithelium, and their diagnosis is often straightforward (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3).

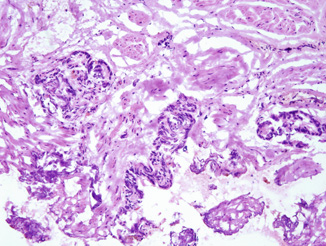

Fig. 10.2

Frozen section of bladder neck tissue showing small malignant glands dissecting smooth muscle bundles in a haphazard infiltrative fashion, although the cytologic details are obscured by cautery and frozen artifacts. Original magnification × 40

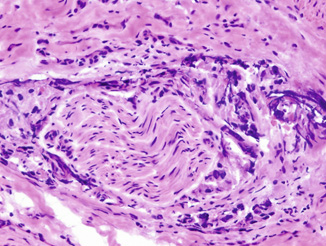

Fig. 10.3

Frozen section of a surgical margin showing fibromuscular tissue with small atypical glands highly suspicious for prostatic carcinoma. Original magnification × 100

Lateral area: When a nerve-sparing procedure is planned, the surgeon may submit a biopsy from the area of the neurovascular bundle. The presence of carcinoma in the biopsy will result in abandonment of nerve sparing on that side. The biopsy is usually quite small and multiple levels should be prepared because cautery artifact may complicate the interpretation (Fig. 10.4). An additional pitfall is that cauterized nests of nerve and ganglion cells that may have prominent nucleoli similar to those seen in prostate cancer cells should not be mistaken for carcinoma with perineural invasion (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.4

Frozen section showing a focus of circumferential perineural invasion by prostatic carcinoma. Marked cautery and frozen artifacts are seen. Original magnification × 200

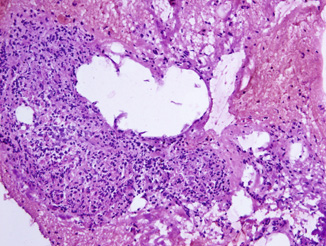

Fig. 10.5

Frozen section of ganglion tissue showing a well circumscribed nest of loosely cohesive cells and occasional large cells with abundant amphophilic cytoplasm and large nucleus, mimicking high-grade prostatic carcinoma. Original magnification × 100

Assessment of Pelvic Lymph Nodes During Radical Prostatectomy

Lymph node dissection is potentially therapeutic when performed with prostatectomy , while nodal metastasis implies disseminated carcinoma and is classically a contraindication for radical surgery. However, an apparent stage migration has been reported in recent years resulting in a significant decrease in the rate of nodal metastasis in men undergoing radical prostatectomy [5]. A number of nomograms that combine preoperative variables, including serum PSA level, clinical tumor stage, biopsy findings (e.g., Gleason score, number of positive cores, percentage of cancer in positive cores), and others (e.g., age, digital rectal examination finding, prostate volume) have been developed to predict pathologic stage and/or the risk of lymph node metastasis [1]. Because the chance of nodal metastasis is minimal in patients with a low or intermediate risk [6], routine FSA of the lymph nodes during radical prostatectomy may be unnecessary. In contrast, nodal dissection is often performed in high-risk patients. When FSA of lymph node is requested, it is critical to avoid false positive diagnosis because positive nodal metastasis identified by FSA may be used by surgeon in making the decision of aborting the radical prostatectomy procedure [7].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree